Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 7, Case 3

Signalment:

12-year-old, neutered male, European, cat (Felis catus)History:

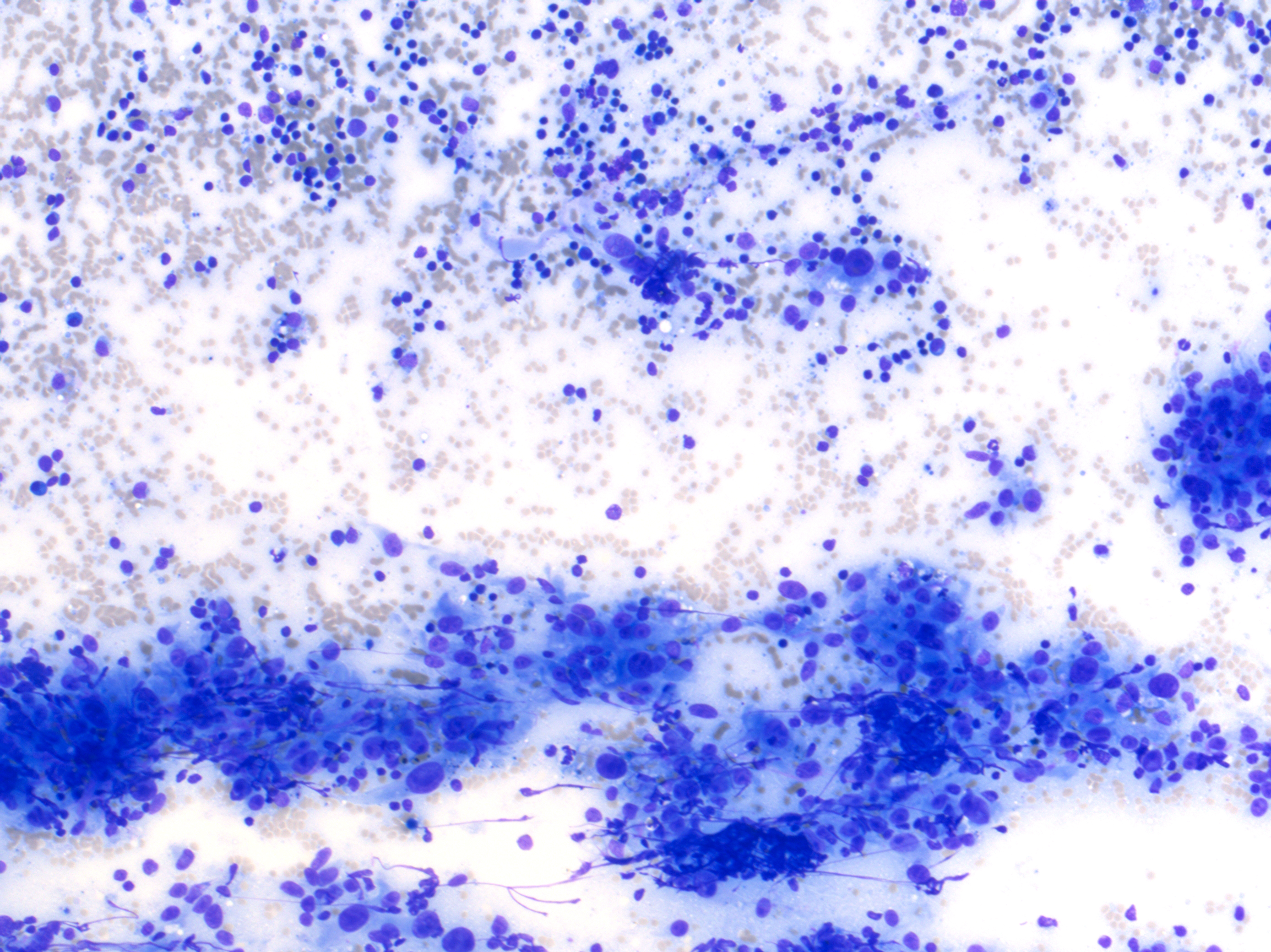

Clinical examination revealed an ovoid, 4 x 6 x 6 cm, firm, well-demarcated, non-painful and non-adherent mass in the cranial right ventro-lateral part of neck. Based on location, a right mandibular lymphadenopathy was suspected and a fine-needle aspiration was performed.Cytological examination revealed a reactive lymphoid population (non-specific hyperplasia) admixed with numerous aggregates of plump and pleomorphic spindle to epithelioid cells that were occasionally separated by a delicate eosinophilic extracellular matrix (Figures 1-3). Atypia were severe with macrokaryosis and irregular macronucleoli but mitoses were not observed. Some siderophages were present. A diagnosis of malignant anaplastic tumor, primary or metastatic, of the right mandibular lymph node was made.

Complete staging, including oral cavity and eyes, did not reveal any other mass and a primary sarcoma of the right lymph node was considered. A needle biopsy was made and revealed a sarcomatous proliferation highly suggestive of hemangiosarcoma. Considering the results of the staging, a primary nodal hemangiosarcoma was considered.

The lymph node was surgically removed and submitted for histopathological examination.

Gross Pathology:

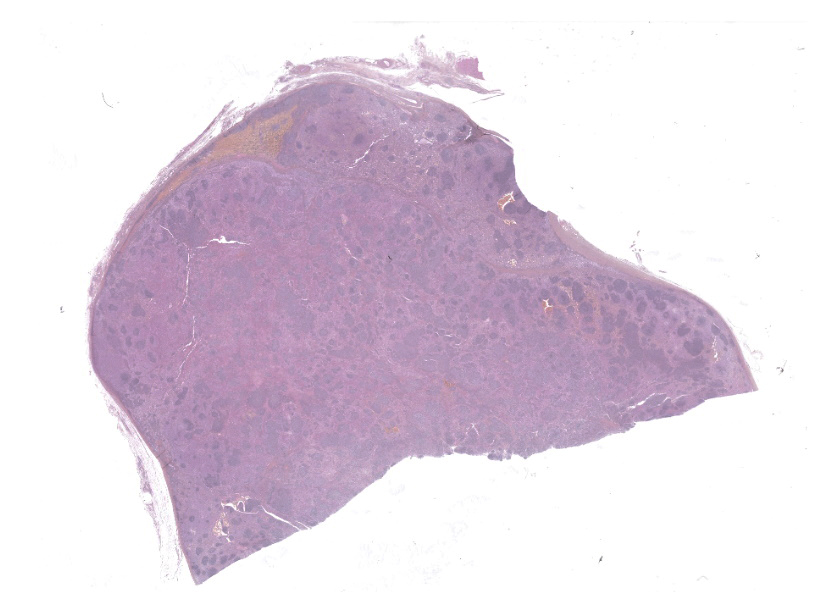

A 4 x 6 x 6 cm lymph node was submitted (Figures 4-6). On cut section (after fixation), the lymphoid tissue was severely compressed and atrophic due to a rather well demarcated, white to dark red, firm to spongy proliferation that occupied 90% of the section. Some cavitary dark foci were present. The proliferation was limited by the nodal capsule and there was no sign of capsular effraction.Laboratory Results:

Complete blood count revealed a mild macrocytic hypochromic and regenerative anemia with poikilocytosis. Numerous schistocytes were observed suggesting a mechanical anemia (fragmentation anemia). Thrombocytosis and moderate neutrophilic leukocytosis were also observed.Microscopic Description:

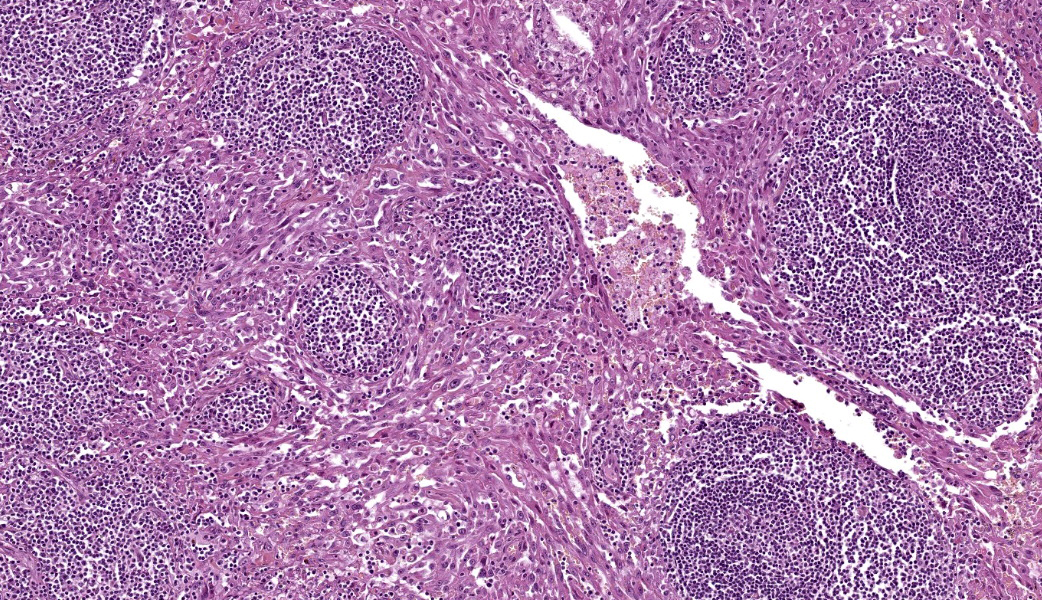

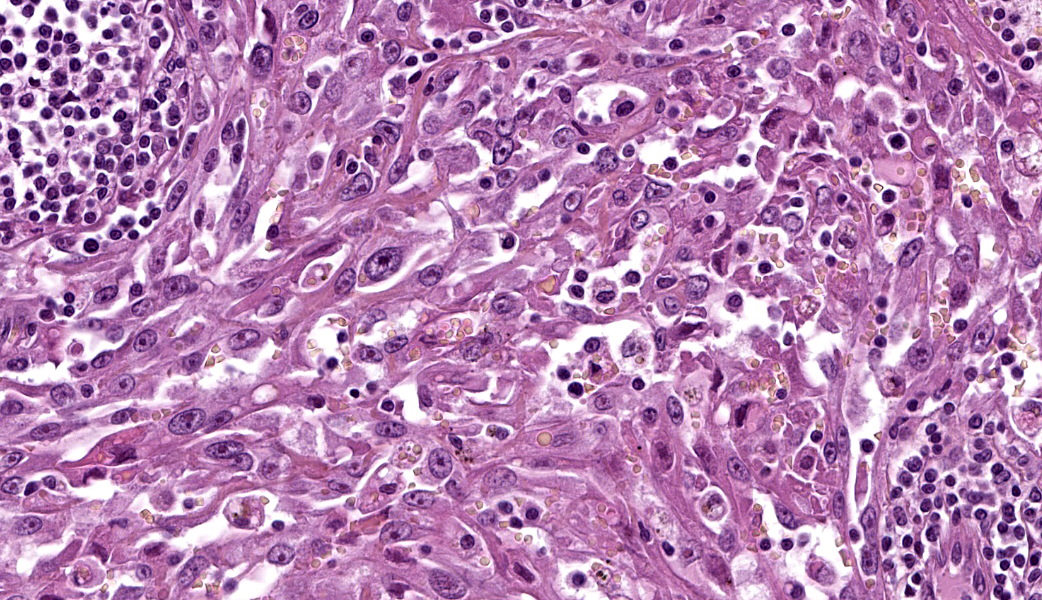

The remaining nodal tissue was atrophic, congested and severely compressed by a densely cellular, well-demarcated, encapsulated neoplasm composed of compact intermingled bundles of spindle to epithelioid cells associated to a delicate fibrous stroma. Neoplastic cells often delineated vascular lumens filled with red blood cells. They measured 50-100 µm, had distinct cell borders, a moderately abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and a round vesicular nucleus with a large eosinophilic nucleolus. Some cells contained intracytoplasmic red blood cells.Pleomorphism and atypical were marked: macrokaryosis, macronucleoli, irregular nuclei, nuclear hyperchromasia etc. Mitotic count was 6 mitoses per HPF (field surface = 0.307 mm²).

The neoplasm incorporated many remaining lymphoid follicles, some of which were hyperplastic. There was also diffuse lymphocytic and plasmacytic infiltration as well as some siderophages and macrophages showing prominent erythrophagocytosis.

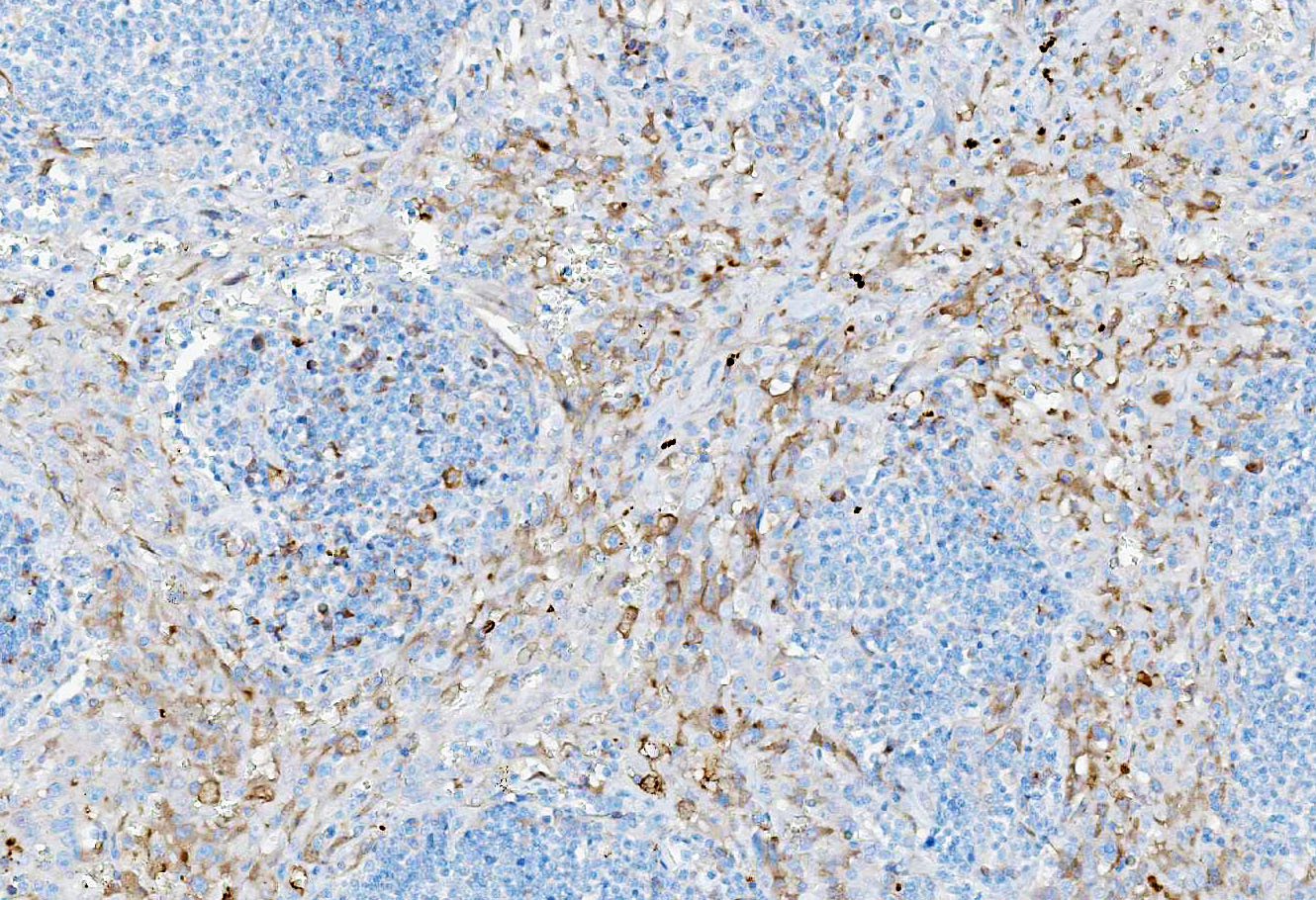

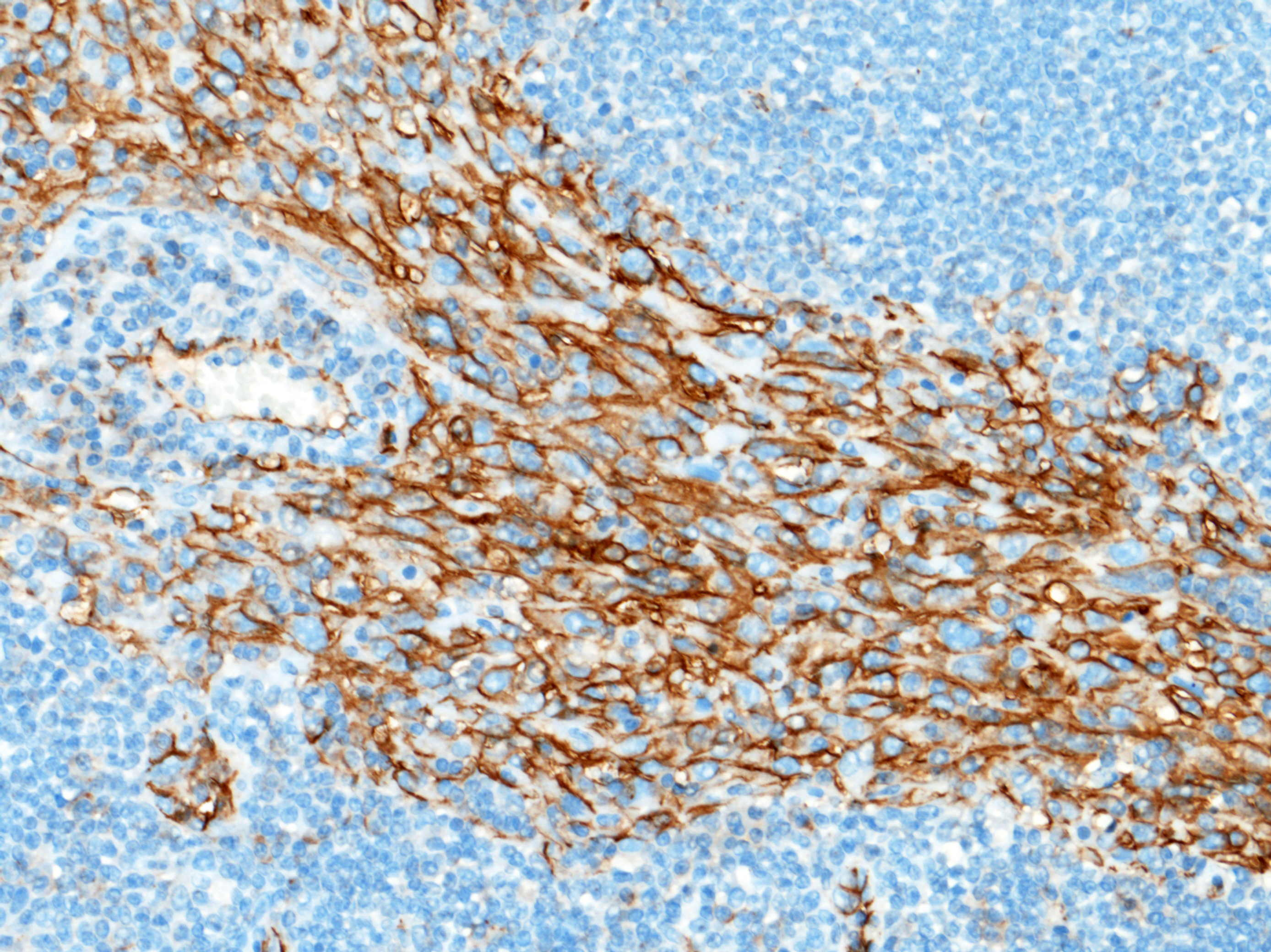

Immunohistochemical staining showed marked positive labelling for vimentin (cytoplasm) and CD31 (membrane) of neoplastic cells. Regarding CD31, normal sinus-lining endothelial cells were also positive.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Right mandibular lymph node: Primary nodal hemangiosarcoma (likely corresponding to malignant transformation of feline plexiform vascularization of cervical lymph nodes).Contributor's Comment:

There are several descriptions of distinctive vascular lesions in cervical lymph nodes of cats.7,8,13,15 They represent a morphologic spectrum ranging from benign lesions (plexiform vasculopathy/vascularization) to clearly malignant neoplasms (hemangiosarcomas).13Feline plexiform vasculopathy/vascularization of lymph nodes (FPVLN) has first been described by Lucke et al. in 1987 and corresponds to nodal capillary vasoproliferation and lymphoid atrophy.8 These lesions have been compared to vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses in humans, a conversion of nodal sinuses to capillary-like channels accompanied by fibrosis.8,10,13 Such lesions have also been described in a dog.5 In humans, such changes are believed to be secondary to occlusion of efferent lymphatics and/or sluggish venous blood ?ow due to thrombotic obstruction, heart failure, or other conditions leading to venous stasis.10 The etiology of FPVLN remains uncertain.

FPVLN has a wide range of age (3 to 16 years old).8,13 As in the single canine case, it mostly affects the cervical lymph nodes, which is different from vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses in humans that is predominantly observed in intra-abdominal lymph nodes.8,10,13,15 FPVLN involving inguinal lymph nodes has also been described and other lymph nodes may rarely be affected (axillary lymph node for example).8,13 Lesions are most often solitary but may also be multiple/bilateral. Generally, affected cats are otherwise clinically normal and prognosis after complete surgical excision is usually considered to be excellent with no recurrence or progression.8,13,15

Grossly, lymph nodes are enlarged, up to 5-6 cm. On cut section, lymph nodes are heterogeneous and appear tan to purple, reflecting follicular structures and congestion respectively.8,13 Histologically, there is lymphoid atrophy and a proliferation of capillary-like vessels lined by a single layer of flattened endothelial cells without atypia. The lumen may contain red blood cells or appear empty. Hyperplastic lymphoid follicles may also be observed.8,13

Recently, the endothelial cells in FPVLN have been proposed to be of lymphatic origin based on their expression of Prox-1 (nuclear labelling) in addition to CD31 and factor VIII-related antigen, the former being specific of lymphatic endothelial cells. LyVe-1 is another specific marker for the lymphatic endothelium.7

In 2015, primary hemangiosarcomas of feline cervical lymph nodes were reported in 12 cats.13 Some cats also had typical lesions of FPVLN suggesting that there is a pathogenic and pathologic continuum between FPVLN and primary nodal hemangiosarcomas, similar to the continuum that exists between injection-associated panniculitis and injection site sarcomas in cats.13 Clinical and gross findings appear similar to FPVLN, indicating that histopathological examination is essential to distinguish both entities. This is all the more important given that the prognosis of primary nodal hemangiosarcoma appears different from FPVLN as recurrence and suspected metastases were reported in some animals.13

Histologically, the proliferation has the classical appearance of malignant vascular neoplasms.13 Although initially considered to be hemangiosarcomas based on the presence of red blood cells within the vascular channels, the recent demonstration that FPVLN arises from lymphatic endothelium suggests that these tumors may actually be lymphangiosarcomas.7 The association of red blood cells with lymphatic endothelial proliferation is also found in Kaposi’s sarcoma, a distinct low-grade vascular sarcoma in humans associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8). There are several forms of Kaposi sarcoma (classic, African, AIDS-associated and iatrogenic). Interestingly, it has been shown that infection with HHV8 reprograms blood endothelial cells to make them upregulate several lymphatic-associated genes such as lymphatic vessel endothelial receptor 1 (LYVE1), podoplanin, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3), so that, in the end, they resemble lymphatic endothelial cells, at least immunohistochemically (Kaposi’s sarcoma is very different histologically from lymphangiosarcoma).12 This example nicely illustrates that, in oncology, the phenotype of neoplastic cells may not accurately reflect the cell of origin. To date, the cause of FPVLN and FPVLN-associated hemangiosarcomas remains unknown and a viral etiology/contribution may be considered.

So far, FPVLN-associated hemangiosarcomas have not been further characterized immunohistochemically so we do not actually know if they also express markers of lymphatic endothelial cells (in this case, LyVe-1/Prox-1 immunohistochemical labelling was not performed). In such conditions, it might be better, regarding the terminology, pathogenesis and nomenclature, to rather name these distinctive lesions “FPVLN-associated angiosarcomas” or to refer to them as “benign vs. malignant forms of FPVLN”.

Other malignant vascular neoplasms in cats include feline ventral abdominal lymphangiosarcoma (a distinctive cutaneous neoplasm previously termed feline ventral abdominal angiosarcoma) and hemangiosarcomas at other sites.4,6,9,11,14 Contrary to dogs, hemangiosarcomas are uncommon in cats, accounting for 0.5% of cases at necropsy.13 Most feline hemangiosarcomas are cutaneous and subcutaneous, with subcutaneous forms being more aggressive.6 Some cutaneous hemangiosarcomas may develop secondary to chronic UV exposure on hypopigmented skin, as in dogs. Corneal and conjunctival hemangiosarcomas have also been described and appear to be associated with a good prognosis if completely excised.11,14 Feline visceral hemangiosarcomas are rare and have a poor prognosis.6 Finally, feline reactive systemic angioendotheliomatosis is a rare, multisystemic intravascular proliferative disorder of cats that most commonly affects the heart. Lymph nodes may occasionally be involved.3

This case represents a typical example of primary nodal hemangiosarcoma in the setting of FPVLN (although typical foci of FPVLN may be difficult to demonstrate in this case due to the extent of the hemangiosarcoma). Cytologic diagnosis yielded a diagnosis of malignant neoplasm, prompting for a complete staging in the search of a primary tumor. As no primary tumor was found and the morphology was not typical of lymphoma, FPVLN-associated hemangiosarcoma was suspected and subsequently confirmed by histological examination. Interestingly, hemangiosarcoma could have also been suggested by the finding of regenerative anemia with numerous schistocytes on hematological examination. Schistocytes usually result from the fragmentation of red blood cells in abnormal small vessels (fragmentation anemia). They are observed mostly in dogs with disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemangiosarcoma, myelofibrosis, glomerulonephritis etc. They are also described in cats with hepatic disease.2 Following the complete excision of the affected lymph node, schistocytes were not found on subsequent blood smears and the animal completely recovered from its anemia.

As a conclusion, differential diagnosis for enlarged cervical lymph nodes in cats should include lymphadenitis, lymphoma (non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin-like), metastases, lymphoid hyperplasia, distinctive peripheral lymph node hyperplasia of young cats, plexiform vascularization and primary (hem)angiosarcoma.13

Contributing Institution:

Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort, Unité d’Histologie et d’Anatomie Pathologique, BioPôle Alfort, Département des Sciences Biologiques et Pharmaceutiques, 7 avenue du Général De Gaulle, 94704 Maisons Alfort Cedex, FRANCE www.vet-alfort.frJPC Diagnoses:

Lymph node: Angiosarcoma.JPC Comment:

This case proved to be a real diagnostic challenge for participants. Much of the discussion of this entity happened in real-time during conference, as most participants were unclear on the diagnosis in this case. The contributor provided an exceptional write-up on this enigmatic entity and makes numerous excellent points for consideration. Their comment is well worth the read and covers most of what was discussed in conference. Participants were initially unsure on tissue identification given the degree of parenchymal effacement by the neoplasm, with some getting to lymph node, but most thinking spleen. There were a few subtle clues to help participants get to the right organ, the most useful of which is the distribution of the extracapsular adipose tissue. Lymph nodes tend to be embedded in and surrounded by adipose tissue, whereas the spleen has only a strip of adipose tissue along its mesenteric side where vasculature enters the splenic body. In addition to covering much of what was stated by the contributor, differential diagnoses for vascular proliferations in feline patients were discussed and included hemangioma, hemangiosarcoma, lymphangioma, lymphangiosarcoma (especially on the inguinal skin), and systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis.As is the nature of science, despite most of the historical literature calling these neoplasms “primary nodal hemangiosarcomas,” there is an increasing body of evidence that the neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for lymphatic endothelial markers (D2-40, Prox-1, LyVe-1).7 The most popular arising school of thought regarding this neoplasm in the context of feline plexiform vasculopathy/vascularization of lymph nodes (FPVLN) is that it is most likely of lymphatic endothelial origin and is part of a continuum of FVPLN, where the proliferating benign vasculature undergoes malignant transformation secondary to obstruction of the efferent hilar lymphatics of the lymph node.7 There is a similar condition to FPVLN that can occur in the mesenteric lymph nodes of rats, and neoplasms arising from affected lymph nodes in these animals have also been immunoreactive to Prox-1 and VEGF.1

In an effort to further contribute information to the speculative origins of this neoplasm, a podoplanin was performed in-house at the Joint Pathology Center (JPC) to try and tease out any lymphatic origin in the neoplastic cells in this case (LyVe-1 or Prox-1 are not available for use at the JPC). Approximately 60% of the neoplastic cells had moderate cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to D2-40 (podoplanin) in this case, which correlates with a lymphatic endothelial origin. CD31, Factor VIII, CD20, and CD3 were also performed. The Factor VIII demonstrated diffuse, strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity within neoplastic cells, while the CD31 had moderate membranous immunoreactivity in approximately 65% of neoplastic cells. Both blood vessel and lymphatic endothelial neoplasms can be immunoreactive to these IHCs. CD3 and CD20 nicely showed the peripheralized follicular architecture of the lymph node, with follicular T-cells and parafollicular B cells demonstrating strong membranous immunoreactivity to CD3 and CD20, respectively. Putting everything in context, conference participants favored the diagnosis of angiosarcoma for this neoplasm.

References:

- Awazuhara Y, Tomonari Y, Kokoshima H, Wako Y, Doi T. Lymphangiomas with the presence of erythrocytes in mesenteric lymph nodes of Wistar Hannover rats. J Toxicol Pathol. 2025;38(1):37-42.

- Barger AM. Erythrocyte morphology. In: Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology. Ames, Iowa: Weiss DJ & Wardrop KJ; 2010:148.

- Fuji RN, Patton KM, Steinbach TJ, et al. Feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis: eight cases and literature review. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:608–617.

- Galeotti F, Barzagli F, Vercelli A, et al. Feline lymphangiosarcoma--definitive identification using a lymphatic vascular marker. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15:13–18.

- Gelberg HB, Valentine BA. Lymphadenopathy associated with a thyroid carcinoma in a dog. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:530–534.

- Johannes CM, Henry CJ, Turnquist SE, et al. Hemangiosarcoma in cats: 53 cases (1992-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007;231:1851–1856.

- Jungwirth N, Junginger J, Andrijczuk C, Baumgärtner W, Wohlsein P. Plexiform Vasculopathy in Feline Cervical Lymph Nodes. Vet Pathol. 2018;55:453–456.

- Lucke VM, Davies JD, Wood CM, Whitbread TJ. Plexiform vascularization of lymph nodes: an unusual but distinctive lymphadenopathy in cats. J Comp Pathol. 1987;97:109–119.

- McAbee KP, Ludwig LL, Bergman PJ, Newman SJ. Feline cutaneous hemangiosarcoma: a retrospective study of 18 cases (1998-2003). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005;41:110–116.

- Miranda RN, Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ. Vascular transformation of lymph node sinus. In: Vol. 2, Atlas of Lymph Node Pathology. New York: Cheng L; 2013:493–494.

- Pirie CG, Dubielzig RR. Feline conjunctival hemangioma and hemangiosarcoma: a retrospective evaluation of eight cases (1993-2004). Vet Ophthalmol. 2006;9:227–231.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289–294.

- Roof-Wages E, Spangler T, Spangler WL, Siedlecki CT. Histology and clinical outcome of benign and malignant vascular lesions primary to feline cervical lymph nodes. Vet Pathol. 2015;52:331–337.

- Shank AMM, Teixeria LBC, Dubielzig RR. Canine, feline, and equine corneal vascular neoplasia: A retrospective study (2007-2015). Vet Ophthalmol. 2019;22:76–87.

- Welsh EM, Griffon D, Whitbread TJ. Plexiform vascularisation of a retropharyngeal lymph node in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1999;40:291–293.