Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

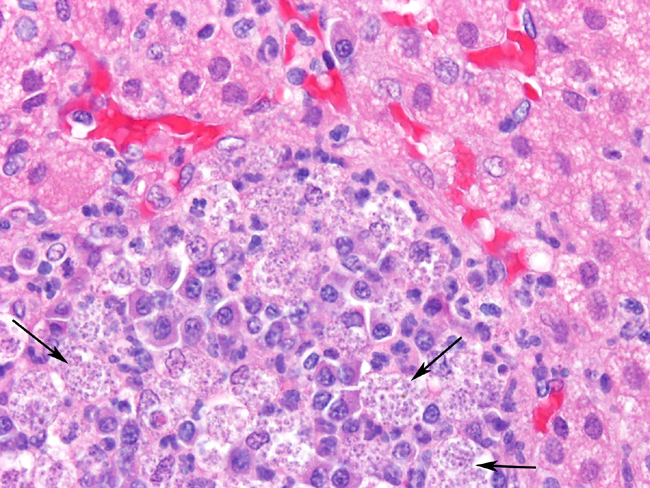

Adrenal glands: Multifocally throughout the adrenal cortex, there are multiple foci of lymphocytes, plasma cell, and macrophages. Many of the macrophages contain numerous small intracellular organisms as described above.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

- 1. Kidney:

- a. Glomerulonephritis, membranous, severe, chronic, diffuse, with multifocal glomerulosclerosis.Â

- b. Interstitial nephritis, lymphoplasmacytic and granulomatous, severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, with intra-histiocytic organisms consistent with Leishmania species.

- 2. Adrenal gland: Adrenalitis, granulomatous and lymphoplasmacytic, moderate, chronic, multifocal with intra-histiocytic organisms consistent with Leishmania species.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Although endemic in southern Central and South America, the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa, this disease is also present in the United States and sporadic cases have been reported, usually travelers returning from an endemic area [5]. In the year 2000, a foxhound kennel in New York reported four foxhounds to be infected with L. infantum [3]. The sandfly vector is present within the United States, although at this time it has not be determined if sandfly transmission of Leishmania occurs in this country. Other mechanisms have been postulated in transmission of canine visceral leishmaniasis and include vector-independent modes such as breeding and direct contact. There may also be a genetic or breed susceptibility to infection, as numerous foxhounds have tested positive and infection appears to be widespread within this breed in the United States, indicating a possible public health threat [2].Â

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney: Glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative, global, diffuse, subacute, marked with multifocal to coalescing lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis, protein casts, and intrahistiocytic amastigotes, etiology consistent with Leishmania sp., American Foxhound (Canis familiaris), canine.

2. Adrenal gland: Adrenalitis, histiocytic, neutrophilic, and plasmacytic, multifocal, moderate, with intrahistiocytic amastigotes, etiology consistent with Leishmania sp.

Conference Comment:

There are three forms of Leishmaniasis:[6]

1. Cutaneous (oriental sore) L. tropica Mediteranean sea

2. Mucocutaneous (espundia) L. braziliensis Central America

3. Visceral (kala-azar) L. donovani Europe, Africa and Asia

The primary insect vectors for Leishmania sp. include the phlebotomine sand flies (Lutzomyia sp. and Phlebotomus sp.). Of the fourteen Lutzomyia sp. in North America, three are known to be capable of transmitting Leishmania mexicana (cutaneous leishmaniasis in Mexico and Texas).[3] Other forms of transmission that have been implicated include mechanical transfer through ticks, shared needles, sexual contact, and bite wounds, as well as transmammary and transplacental transmission.[5]

Upon phagocytosis by macrophages, the organism survives within the phagolysosome despite the activated proteinases and the low environmental pH (4.5-5.0).[4] Studies of the cutaneous form of leishmaniasis in mice caused by L. major indicate immunity depends on an IL-12 driven CD4+, TH1-type response with production of IFN gamma. A CD4+, TH2-type response with production of IL-4 and IL-10 results in susceptibility.[3]

The initial case of visceral Leishmaniasis in a fox hound in North America occurred in 1980.[5] Since that time, visceral leishmaniasis caused by the Leishmania donovani complex (L. donovani, L. infantum, L. chagasi) has been identified in 21 states in the U.S. and 2 Canadian provinces.[5]

References:

2. Duprey ZH, Steurer FJ, Rooney JA, Kirchhoff LV, Jackson JE, Rowton ED, Schantz, PM: Canine visceral leishmaniasis, United States and Canada, 2000-2003. Emerg Infect Dis 12:440-446, 2006

3. Gaskin AA, Jackson J, Birkenheuer A, Tomlinson L, Gramiccia M, Levy M, Steurer F, Kollmar E, Hegarty BC, Ahn A, Breitschwerdt EB: Visceral leishmaniasis in a New York foxhound kennel. J Vet Intern Med 16:34-44, 2002

4. Roberts LJ, Handman E, Foote SJ: Science, medicine, and the future: Leishmaniasis. BMJ 321:801-804, 2000

5. Schantz PM, Steurer FJ, Duprey AH, Kurpel KP, Barr SC, Jackson JE, Breitschwerdt EB, Levy MG, Fox JC: Autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in dogs in North America. J Am Vet Med Assoc 226:1316-1322, 2005

6. Valli VEO: Hematopoietic system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 4th ed., vol. 3, pp. 302-304. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007