CASE IV:

Signalment:

A young wild Mute Swan (Cygnus olor)

History:

This young Mute Swan was found dead at the edge of a large pond at a zoological garden. No other history provided.

Gross Pathology:

The bird weighed 1.7 kg and there was almost zero visceral or subcutaneous fat reserves. As this was a young animal (within the first few months of life) neither the pectoral muscles nor feathers were fully developed for flying. The proventriculus was slightly enlarged. On cross-section the proventricular mucosa was thickened and the lumen was narrowed and empty except for a moderate amount of cloudy whitish mucoid fluid. Within the proximal proventriculus, at the esophageal-proventricular junction there were multiple, approximately 1 cm diameter, firm, nodular lesions within the mucosa. These nodules were distributed in a circumferential pattern. There were a few similar lesions in the distal proventriculus. On cut-surface some of these lesions extended transmurally. Others were shallower and affected only the mucosa and submucosa. All the lesions had a central core which was gritty and pale-grey to white.

Laboratory Results:

Aeromonas hydrophila and A. caviae were isolated from the lungs.

Eggs recovered from the feces were consistent with Echinuria uncinata.

Microscopic Description:

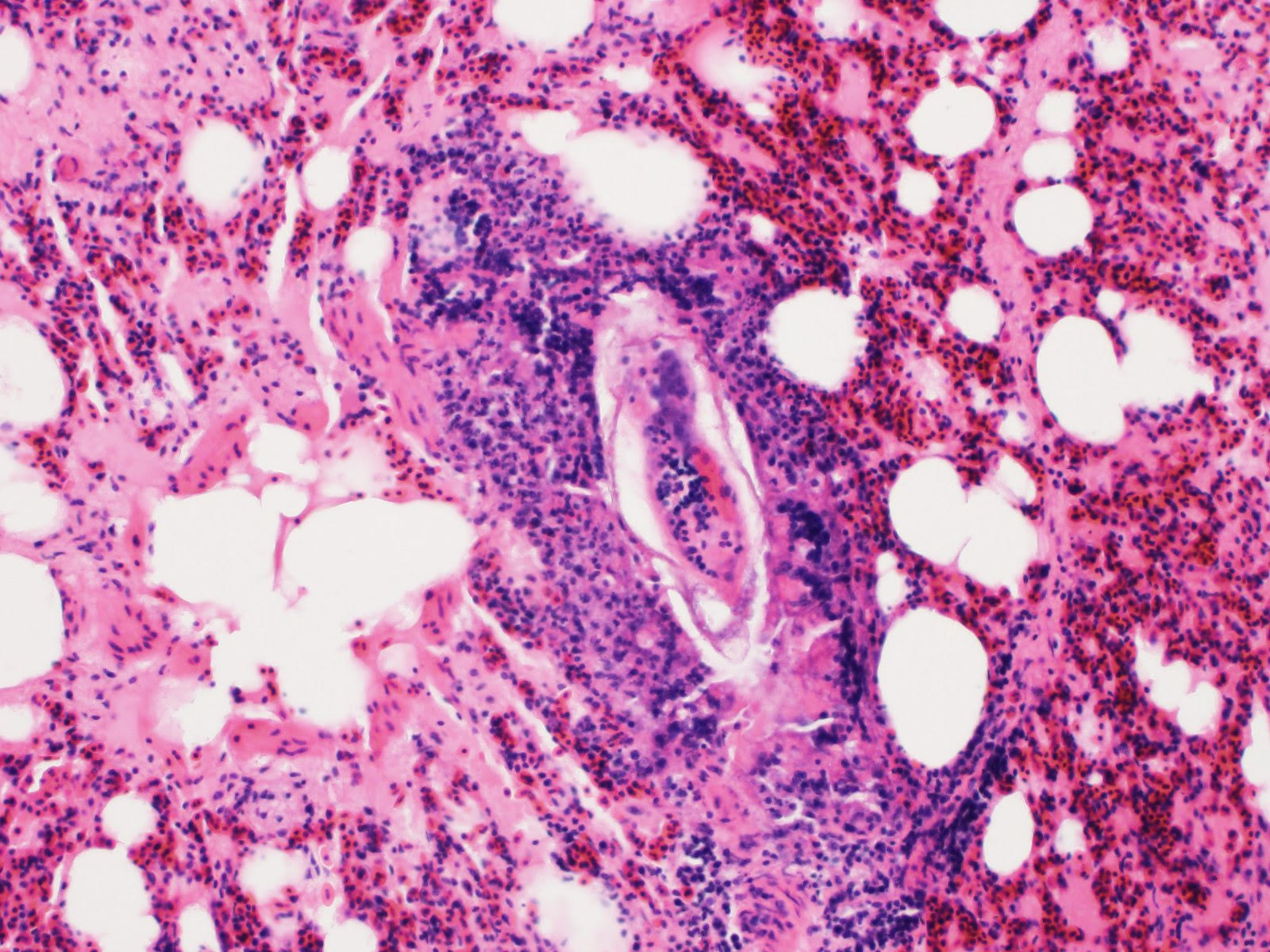

Proventriculus: The mucosa of the proventriculus is disrupted and replaced by large numbers of inflammatory cells which consist mostly of viable and degenerate heterophils, with lesser numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as cellular debris, fibrin and hemorrhage. There is almost complete loss of mucosal glands. This inflammatory debris extends into and partially occludes the proventricular lumen. Multifocally within the mucosal zone there are numerous sections of parasitic worms (nematodes) and eggs. These worms are surrounded by abundant mixed inflammatory cells, fibrosis, cellular debris, hemorrhage and fibrin. The worms are approximately 250-400µm wide with a 5µm thick cuticle. The cuticle is thickened at regular intervals by many prominent longitudinal ridges. The worms have coelomyarian musculature, a pseudocoelom, and a digestive tract lined by columnar epithelium. The majority of worms within the sections are females and contain myriad eggs. Eggs are oval (sometimes with blunt ends), thick-shelled and most are embryonated. Eggs measure approximately 38µm in length and 18µm in width. Eggs are present both within the nematodes and also scattered extra-corporeally, mixed amongst the inflammatory debris. Underlying the mucosa, the normal boundary between the mucosal and submucosal layers is obscured by inflammation. Multifocally the muscle layers of the proventriculus are markedly disrupted by inflammatory cells (mostly heterophils). The serosa is also disrupted by marked numbers of heterophils.

Other histological findings of note in this bird included marked hepatic amyloidosis and multifocal moderate heterophilic and lymphocytic pneumonia.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Proventriculus: Severe, chronic-active, heterophilic ulcerative and necrotizing proventriculitis, with intra-lesional nematodes and eggs consistent with Echinuria uncinata.

Contributor's Comment:

This bird was in poor body condition and it is likely that it died from a combination of factors including debilitation from reduced food intake due to the parasitic lesions in the proventriculus, the effects of liver dysfunction due to hepatic amyloidosis, and pneumonia.

The lesions within the proventriculus are typical of changes seen due to heavy infection with Echinuria uncinata. Birds with significant infections are usually weak and in an emaciated condition with a prominent keel.3 They may have a reduced appetite, and in heavy infections the lesions in the proventriculus may cause reflex retching or choking-like signs if the affected birds attempt to eat. 3

Birds infected with E. uncinata can have a grossly enlarged proventriculus due to worms becoming encapsulated within the mucosal layer.3,5 The nodules eventually become granulomatous,5 although for the cygnet in the current case, there was widespread destruction of normal parenchyma and classic granulomas were not seen. In fatal infections, the parasitic nodules and resultant inflammation can cause occlusion of the proventriculus preventing the passage of food.3 This was the likely outcome in the current case.

E. uncinata is a nematode parasite of numerous species of birds3,5 and has a wide geographical distribution, being reported from India3, Europe3, North America3, South America5, Japan12, Hawaii11 and Australasia.4 Many species of waterfowl are affected due to infection with this parasite, although the most significant clinical effects are reportedly seen in anatids (ducks, geese and swans). Approximately 14 species of Echinuria are recognized1 but E. uncinata appears to be the species that shows most pathogenicity with attendant clinical effects.3

Species of Echinuria have a definitive vertebrate host and an intermediate invertebrate host.3 Definitive hosts for E. uncinata are birds, mostly waterfowl, while freshwater crustaceans of the genus Daphnia (water-fleas) act as intermediate hosts.3

After ingestion of infected species of Daphnia by avian hosts, the third-stage larvae of E. uncinata are released and disseminate throughout the proventriculus where they further develop to the adult stage. The prepatent period is approximately 30-40 days.3

In temperate climates (as was the situation in this case), the numbers of larvae in intermediate hosts reach their highest numbers in midsummer.5 In the district where the swan in this case was found, the total rainfall for the previous four months was reduced by 57% compared to the average rainfall during the same months over the previous five years. This resulted in a widespread reduction of water levels in rivers, lakes and ponds. In addition, air temperatures and hours of sunshine were higher for the season in which the swan was growing, compared to the average for the region, which would also have increased evaporation from already depleted water-sources. The effect of this will have been crowding of water-sources by waterfowl and concomitant increased fecal contamination and thus increased exposure to water-borne parasites. This has previously been reported for ducks infected by E. uncinata on Hawaiian islands11 and in Canada.3 It is highly likely that the combination of low rainfall and increased contamination of waterways led to this particular cygnet becoming infected by high numbers of the parasite.

In addition to the proventricular lesions, this bird also had hepatic amyloidosis. Amyloidosis is reported to be a relatively common finding in adult swans7,8,9,10 and its incidence appears to increase with age.10 In a study on Mute Swans in Japan, up to 78% of adult Mute Swans examined were found to have amyloidosis with the liver being the organ most commonly affected.10 Causes of amyloidosis in swans include chronic inflammation from 'bumblefoot' or other chronic bacterial infections or parasitic infections.8,9,10 In contrast to previous studies of swans with amyloidosis, the bird in the current case was quite young. However, it is still reasonable to assume that the accumulation of amyloid was as a consequence of the chronic inflammation in the proventriculus.

Aeromonas hydrophila and A. caviae were isolated from the lungs of this swan. Both are opportunistic pathogens that concentrate in stagnant waters, and are known to infect water-dwelling animals such as fish and amphibians. Although no bacteria were obvious in the sections of lung examined, the bird did have histological lesions in the lung consistent with a bacterial pneumonia.

Contributing Institution:

Room 012, Veterinary Sciences Centre, School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland http://www.ucd.ie/vetmed/

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Proventriculus: Proventriculitis, hetero-philic, chronic-active, multifocal, severe with glandular loss and adult male and female spirurid nematodes and eggs.

2. Lung, arterioles, tunica media: Hypertrophy and hyperplasia, circumferential, diffuse, severe.

3. Lung: Pneumonia, heterophilic and histio-cytic, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment:

Initially described as Spiroptera uncinatia by Rudolphi in 1819, this nematode's genus was later transferred to Echinuria, following Soloviev's addition of the genus to the family Acuariidae for a nematode he described in 1912 as Echinuria jugadornata, which was likely the same species.1 Hamann is credited with the discovery of E. uncinata's intermediate crustacean hosts in genus Daphnia in 1893, although up to five additional genera have since been shown to support the development of third-stage larvae.3

Echinura are spiruids and belong to the superfamily Acuarioidea, which includes 28 genera, the majority of which are avian parasites. All have characteristically large pseudolabia and cuticular structures located on the anterior aspect known as cordons.3 Of the approximately 15 species of Echinuria, which are predominately reported in waterfowl, E. uncinata is the most significant pathogen. Characteristic features of this species, as well as others within its genus, include recurving cordons that extend posteriorally from the anterior aspect, as well as cuticular spines that run along the length of the body. As demonstrated in this case, there is sexual dimorphism with larger females that are nearly twice the length of males, measuring 12-18 mm long compared to 8-10 mm, respectively.3

Interestingly, there is interspecies variation amongst waterfowl in regard to susceptibly, with very low susceptibility reported in Northern Shovelers (Ana clypeata), a species that frequently feeds on Daphnia species. The most susceptible species include domestic geese, Mallards, Gadwalls (Anas strepera), Northern Pintails (Anas acuta), and Common Eiders (Somateria mollissima). In addition to Northern Shovelers, American Coots (Fulica americana), Ruddy Ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis), and the Blue-winged Teal (Anas discors) are typically resistant.3

Other nematodes that may inhabit the proventriculus of birds include other spiurids such as Tetrameres spp. and Streptocara spp., as well as Amidostomum, a trichostrongyloid. Morphologically, presence of characteristic cuticular spines that extend posteriorly from the anterior end is a unique feature of genus Echinuria that allows for differentiation from other spiruids. In addition, E. uncinata is most commonly found in the proventriculus whereas species of Streptocara and Amidostomum are most often found in the ventriculus.3

Conference attendees noted multifocal pulmonary heterophilic granulomas addition to diffuse hypertrophy and hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells within the tunica media of arterioles. Although not present within the digital slide used for this conference, extracellular structures reminiscent of poorly preserved schistosome eggs are rarely observed within granulomas in accompanying glass slides submitted with this case. Schistosomes are trematodes that live within the circulatory system and can cause proliferative vascular lesions and endophlebitis.6 Adults predominantly live within the mesenteric veins or branches and their eggs are disseminated throughout the body. Anseriformes are infected by eight genera, including Allobilharzia, Austrobilharzia, Bilharziella, Dendritobilharzia, Gigantobilharzia,

Jilinobilharzia, Macrobilharzia, and Trichobilharzia.6

References:

1. Ali M: Studies on spiruroid parasites of Indian birds. Part II. A new genus and five new species of Acuariidae, together with a key to the genus Echinuria. J Helminthol 42: 221-242, 1968

2. Brassard A: Amyloidosis in captive Anseriformes. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci 29: 253?258, 1965.

3. Carreno RA: Dispharynx, Echinuria, and Streptocara. In: Parasitic diseases of wild birds. eds. Atkinson CT, Thomas NJ, Hunter DB. pp. 326-342. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Iowa, IA, USA, 2008.

4. Clark WC: New Zealand grey duck a new host for Echinuria uncinata (Nematoda: Acuariidae) - Correspondence. NZ Vet J 25: 39, 1977.

5. da Silveira E, Amato JFR, Amato SB: Echinuria (Rudolphi)(Nematoda, Acuariidae) in Netta peposaca (Vieillot) (Aves, Anatidae) in South America. Rev Bras Zool 23(2):520-528, 2006.

6. Fenton H, McManamon R, Howerth EW. Anseriforms, ciconiiformes, charadriiforms, and gruiformes. In: Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Inc. 2018:699.

7. Landman WJM, Gruys E, Gielkens ALJ: Avian amyloidosis. Avian Pathol 27: 437?449, 1988.

8. Meyerholtz DK, Vanloubbeeck YF, Hostetter SJ, Jordan DM, Fales-Williams AJ: Surveillance of amyloidosis and other diseases at necropsy in captive trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator). J Diagn Invest 17:295-298, 2005.

9. Sato A, Koga T, Inoue M, Goto N: Pathological observations of amyloidosis in swans and other Anatidae. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 43: 509?519, 1981.

10. Tanaka S, Dan C, Kawano H, Omoto M, Ishihara T: Pathological study on amyloidosis in Cygnus olor (mute swan) and other waterfowl. Med Mol Morphol 41: 99-108, 2008.

11. Work TM, Meteyer CU, Cole RA: Mortality in Laysan ducks (Anas laysanensis) by emaciation complicated by Echinuria uncinata on Laysan Island, Hawaii, 1993. J Wildlife Dis 40(1):110-114, 2004.

12. Yoshino T, Uemura J, Endoh D, Asakawa M. Parasitic nematodes of anseriform birds in Hokkaido, Japan. Helminthologia 46(2): 117-122, 2009.