Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Additionally, there was lymphohistiocytic interstitial nephritis and similar infiltrates noted within the capsular and sub-capsular regions of the adrenal gland. Congestion, focal hemorrhage, lymphoid depletion and medullary histiocytic infiltration (including hemosiderophages) were evident in lymph nodes. Hemosiderophages present in alveolar septa.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The lentivirus causing EIA is considered to have little direct cytopathic effect and with the pathogenesis involving indirect effects of the immune response.6 Anemia co-rresponds with the appearance of circulating antibody, which is complement-fixing but not initially virus-neutralizing. C3 appears on erythrocyte membranes, and probably ex-plains the erythrophagocytosis. Antibodies are believed to react with virus adsorbed to erythrocytes which results in complement activation and red cell destruction of the "innocent bystander" type. The lifespan of red blood cells is typically shortened by up to 65% and the hemolysis that occurs is largely intracellular. The bone marrow is initially highly responsive but ultimately becomes hypoproliferative.6

In 2006, an outbreak of EIA occurred in the Republic of Ireland in four foals following administration of contaminated hy-perimmune plasma imported from Italy. The disease spread by iatrogenic transmission, resulting in 38 cases.3 Disease was confirmed by agar gel immunodiffusion, ELISA, immunoblot and using a novel PCR technique.1 This outbreak highlighted the threat posed to animal populations by the use of unregulated veterinary medicines.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In addition to anemia, thrombocytopenia is also a component of equine infectious anemia, sharing the same mechanism as the anemia. The thrombocytopenia may be reflected in acute cases where petechial hemorrhages are evident under the tongue and on the ocular and vulvar mucosa. The majority of hemolysis is intravascular and during acute disease may be severe enough to result in debilitation and death. During the initial stages of infection, the anemia is regenerative but eventually becomes non-regenerative.7 The anemia is due to hemolysis from secondary antibody and complement fixation as described above; but is also due to inhibition of erythropoiesis, and impaired bone marrow response is likely due in part to mechanisms associated with anemia of inflammation.2 Leukopenia and a relative monocytosis may also be seen, as well as erythrophagocytosis, a feature noted in this case. Chronically, the bone marrow is hypoplastic and there is sinusoidal expansion imparting a grossly red appearance to the bone marrow. A plas-macytosis may also be seen within the bone marrow in chronic cases.7

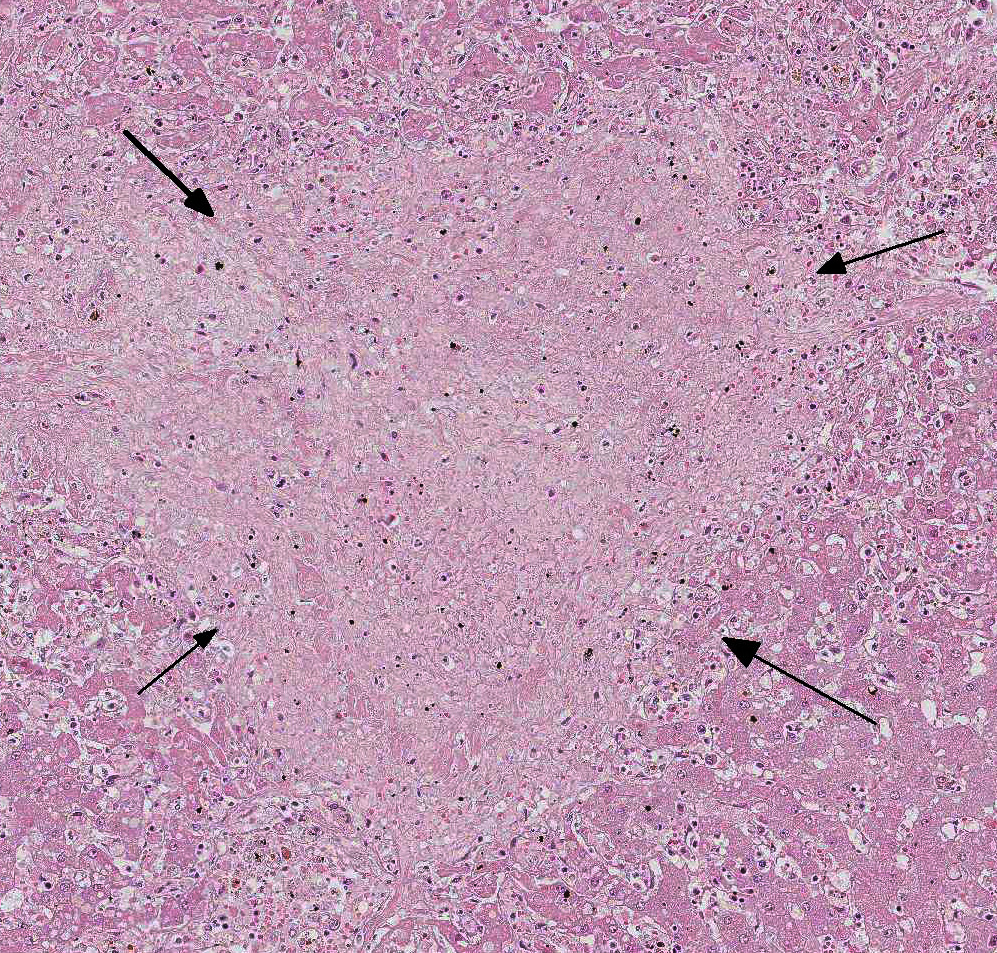

Gross lesions inc-lude splenomegaly, ventral edema, pe-techial hemorrhage in the kidneys, and degree of reddening within the bone marrow noted to be in direct proportion to disease duration.7 Capsular hemor-rhage may be seen on both the liver and spleen; the liver may also have a fine lobular pattern. Micro-scopic lesions vary with duration but can be seen in most tissues. The heap-tic changes vary in range and severity and include per-iportal infiltrates (as seen in this case), atrophy of hepatic chords and sinusoidal dilation, increased perioportal connective tissue, and Kupffer cell hyperplasia. Hemorrhage and necrosis may be seen in centrilobular areas in acute cases and hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration in subacute cases. Regardless of the stage of infection, whether quiescent or in clinical relapse, the presence of increased hemosiderin laden macrophages provides evidence of infection. Splenic follicles may be enlarged but appear hypocellular and, acutely, the spleen will be congested. 7

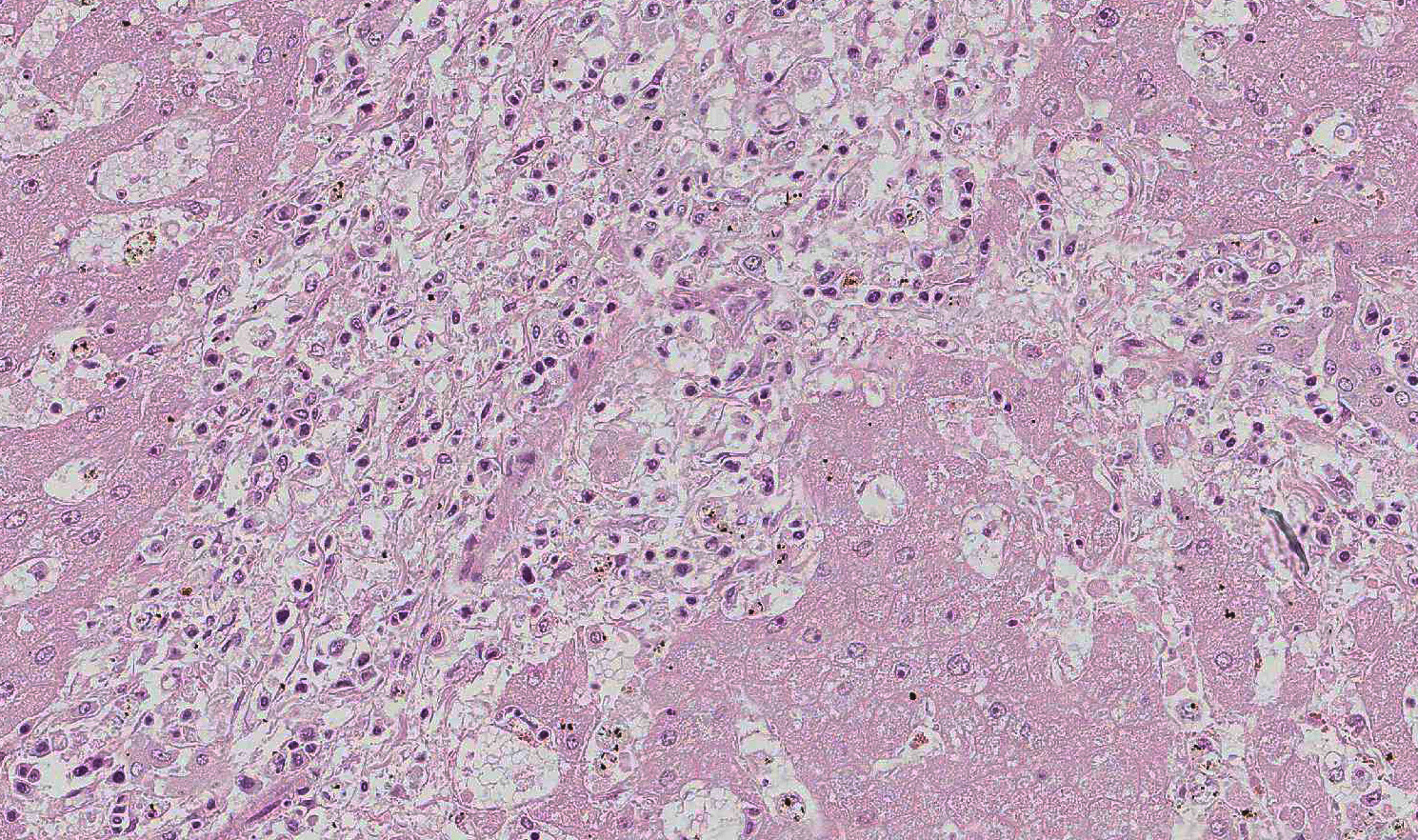

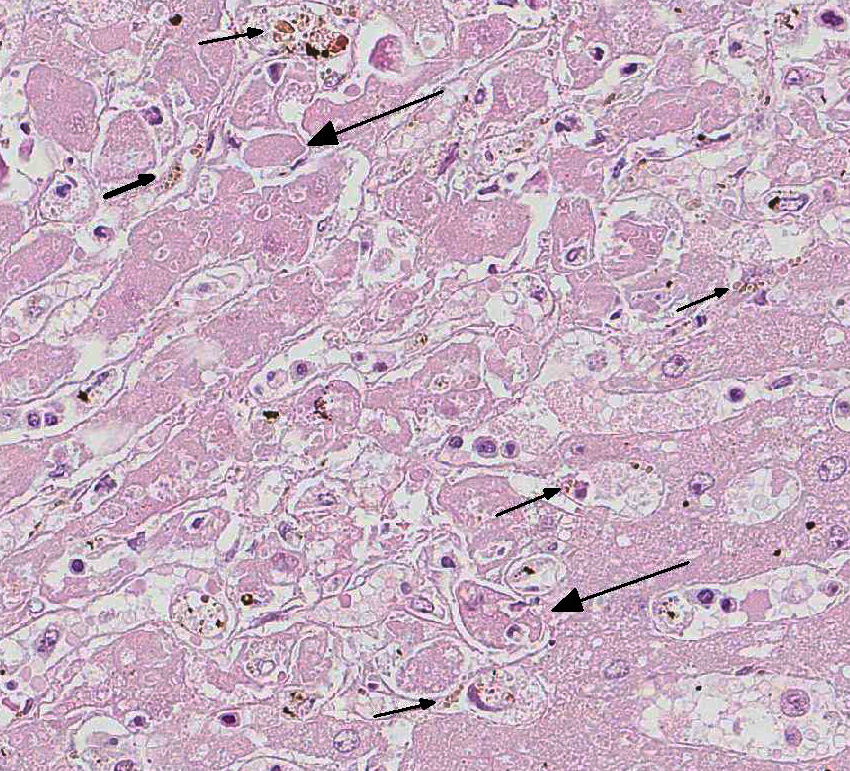

In this case, there is increased pallor of portal areas at subgross histologic examination due to the presence of increased fibrous connective tissue; multifocally, portal areas are also infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages. Low to moderate numbers of periportal hepatocytes are necrotic and mild hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration is present at the margin of affected areas. Cholestatic bile canaliculi and occasional eryth-rophagocytosis are also histologic features noted in this case. Multifocally within centrilobular areas, there is hepatocellular necrosis, as well as fibrosis; these findings reflect a degree of hypoxemia most likely secondary to anemia.

During the conference, the moderator commented on the uncommon nature of active hepatitis in the horse liver; and some conference participants described vasculitis as a prominent component in this section of liver leading some to list equine viral arteritis virus (the causative agent of equine viral arteritis) as their main differential diagnosis. Vasculitis can be seen in cases of EIA. Other features described and discussed during the conference include mild portal to centrilobular bridging fibrosis and mesothelial hypertrophy.

References:

2. Grimes CN, Fry MM. Nonregenerative Anemia: Mechanisms of decreased or ineffective erythropoiesis. Vet Pathol. 2015; 52(2):298-311.

3. More SJ, Aznar I, Bailey DC, Larkin JF, et al. An outbreak of equine infectious anaemia in Ireland during 2006: Investigation methodology, initial source of infection, diagnosis and clinical presentation, modes of transmission and spread in the Meath Cluster. Eq Vet J. 2008; 40: 706-708.

4. Schwartz EJ, Nanda S, Mealey RH. Antibody escape kinetics of Equine infectious anemia virus infection of horses. J Virology. 2015; 89(13):6945-695.

5. Sellon DC, Perry ST, Coggins L, Fuller FJ. Wild-type equine infectious anemia virus replicates in vivo predominantly in tissue macrophages, not in peripheral blood monocytes. J Virol. 1992; 66:5906-5913.

6. Valli VEO: Hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007: 235-239.

7. Valli VEO, Kiupel M, Bienzle D. Hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 3. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:114-116.