Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 18

12 February, 2020

Timothy Cooper, DVM, PhD, DACVP

Pathology Department

NIH/NIAID

Integrated Research Facility

Frederick, MD

CASE I: 17-325 (JPC 4105224).

Signalment: 8-month, male intact Old English Sheepdog, Canis familiaris, dog

History: The dog was presented to the Internal Medicine Service for evaluation of a 4 month period of daily vomiting, frequent diarrhea, depression following meals, and lack of weight gain.

Gross Pathology: A large mass of vessels was seen surrounding gallbladder and infiltrating into the liver at surgery. A biopsy including the gallbladder, vessels, and adjacent hepatic parenchyma was submitted for histopathology.

Laboratory results: Serum chemistry revealed elevations in activity of ALP (204IU/L) and ALT (76IU/L); serum ammonia concentration was elevated at 40umol/L. Complete blood count revealed a moderate, normocytic, normochromic anemia with a hematocrit of 24.6%. A CT confirmed the presence of a large arterioportal malformation centered at the gallbladder and falciform fat as well as multiple acquired extrahepatic portosystemic shunts, moderate ascites, and left-sided liver atrophy.

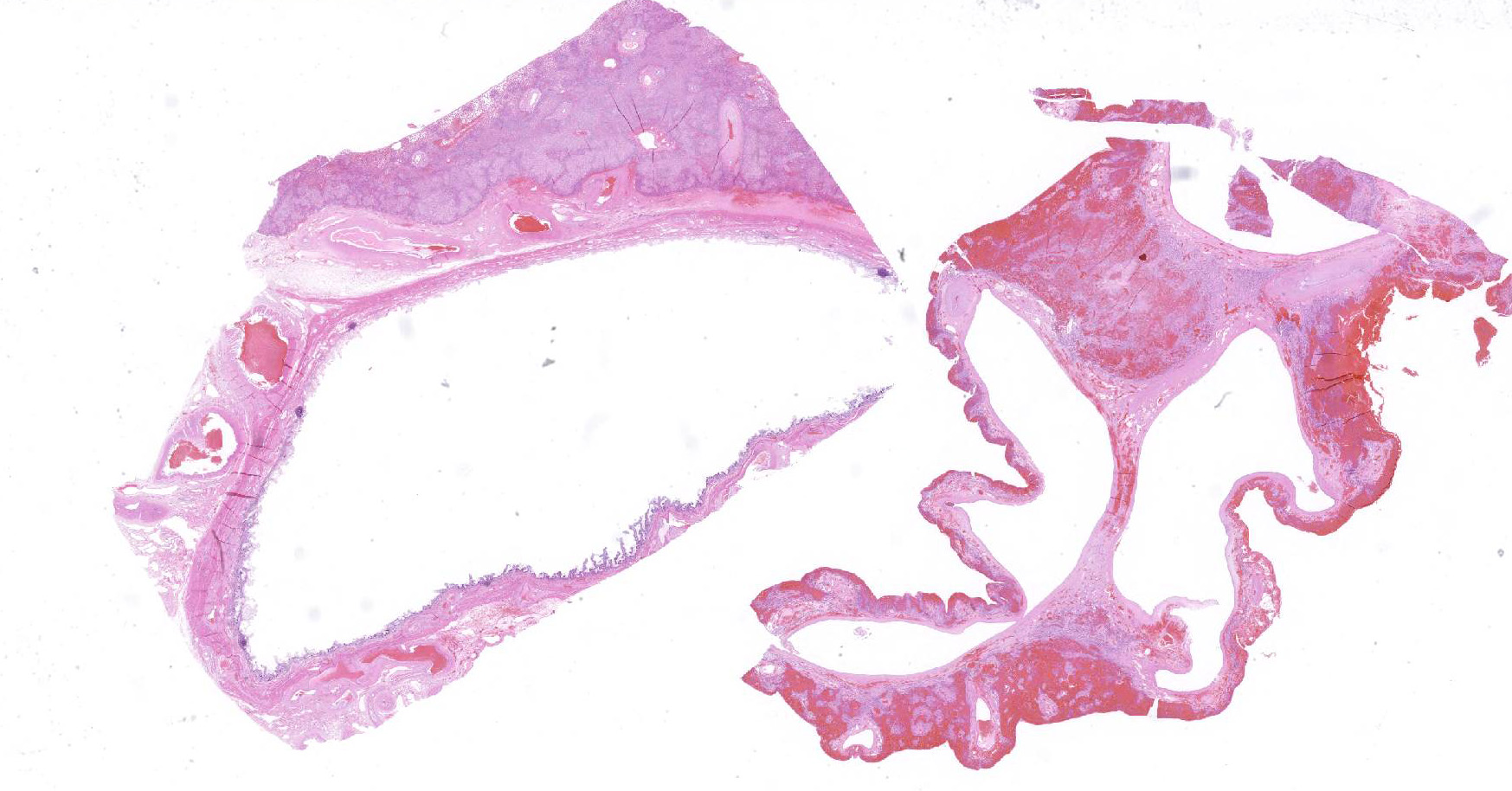

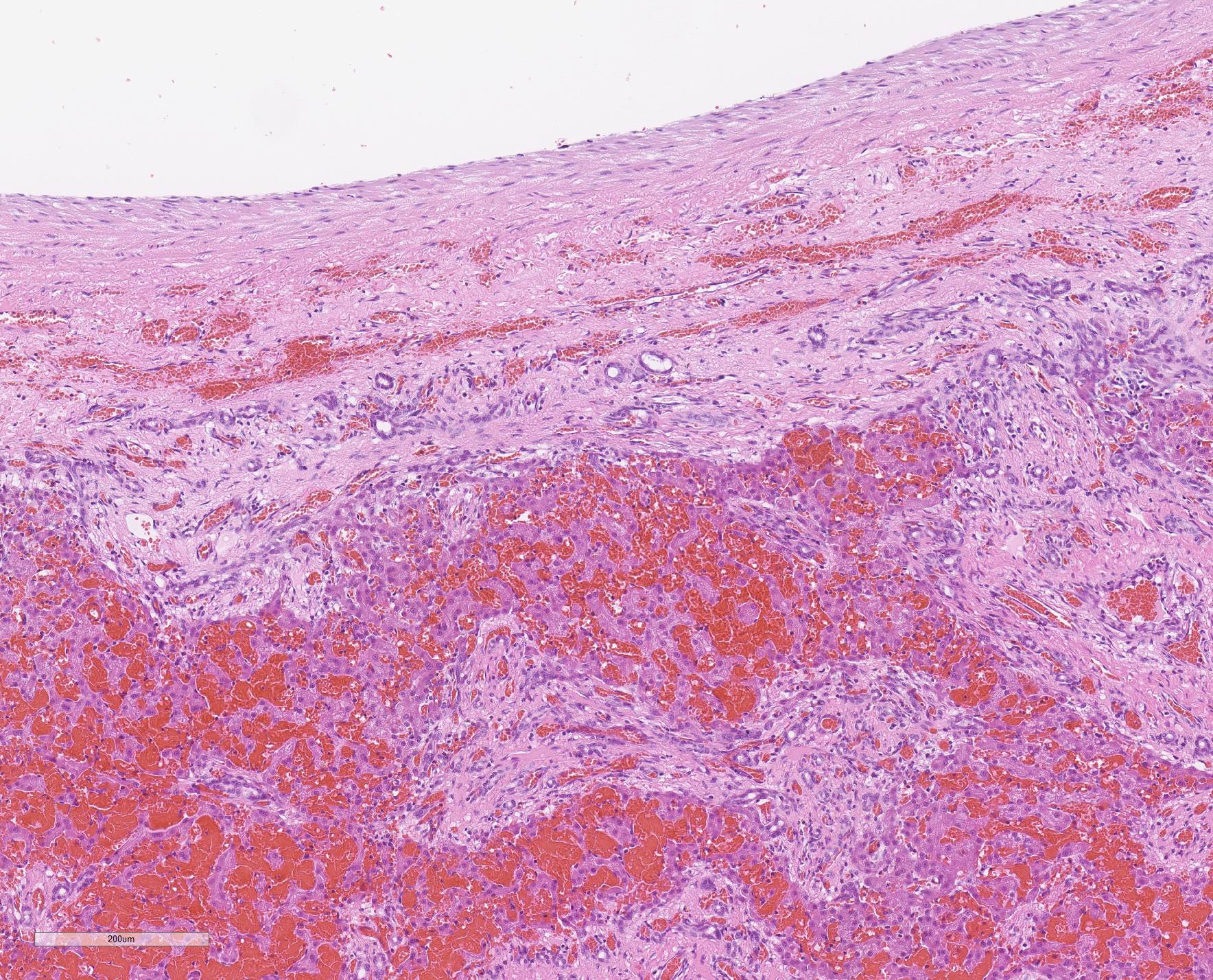

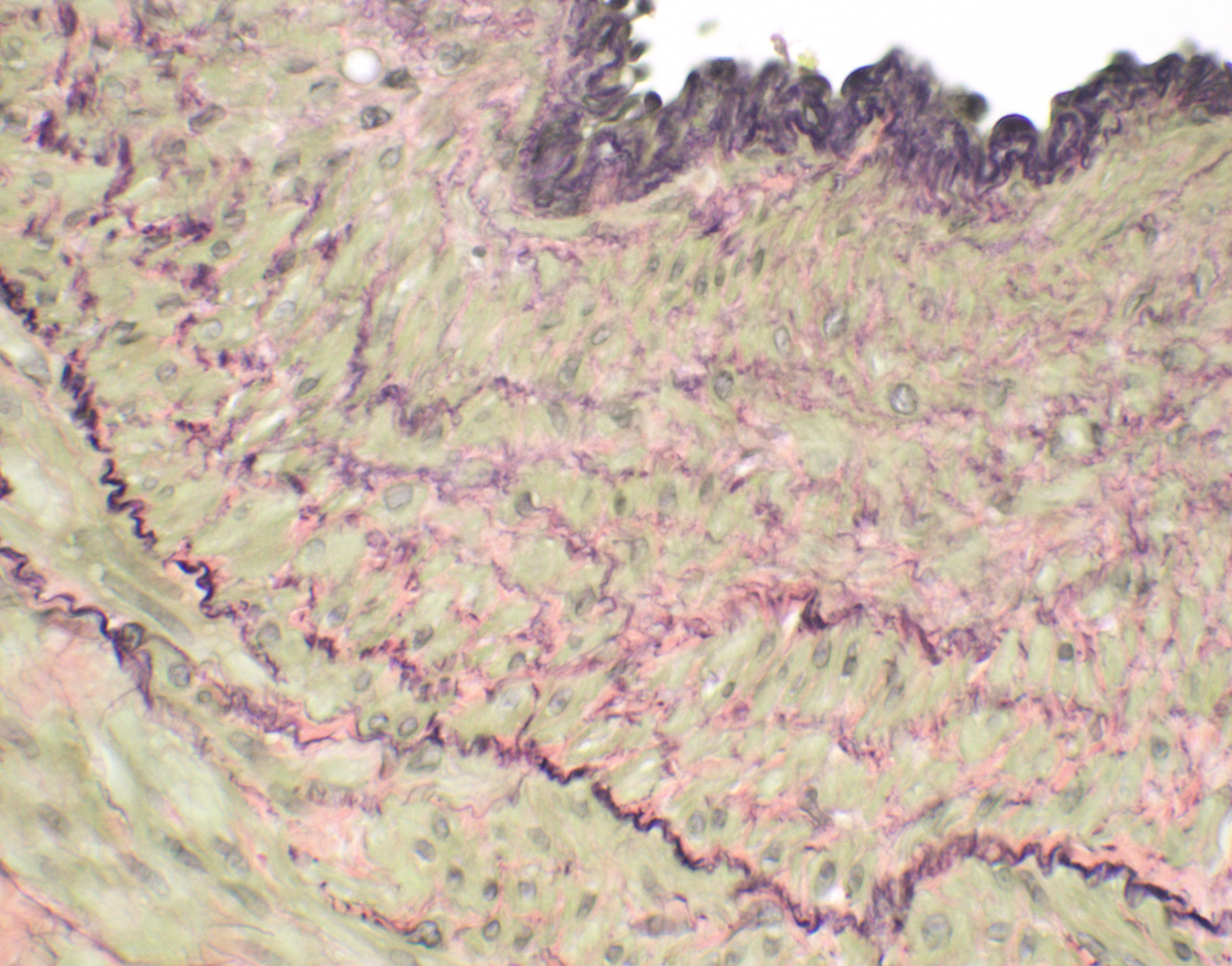

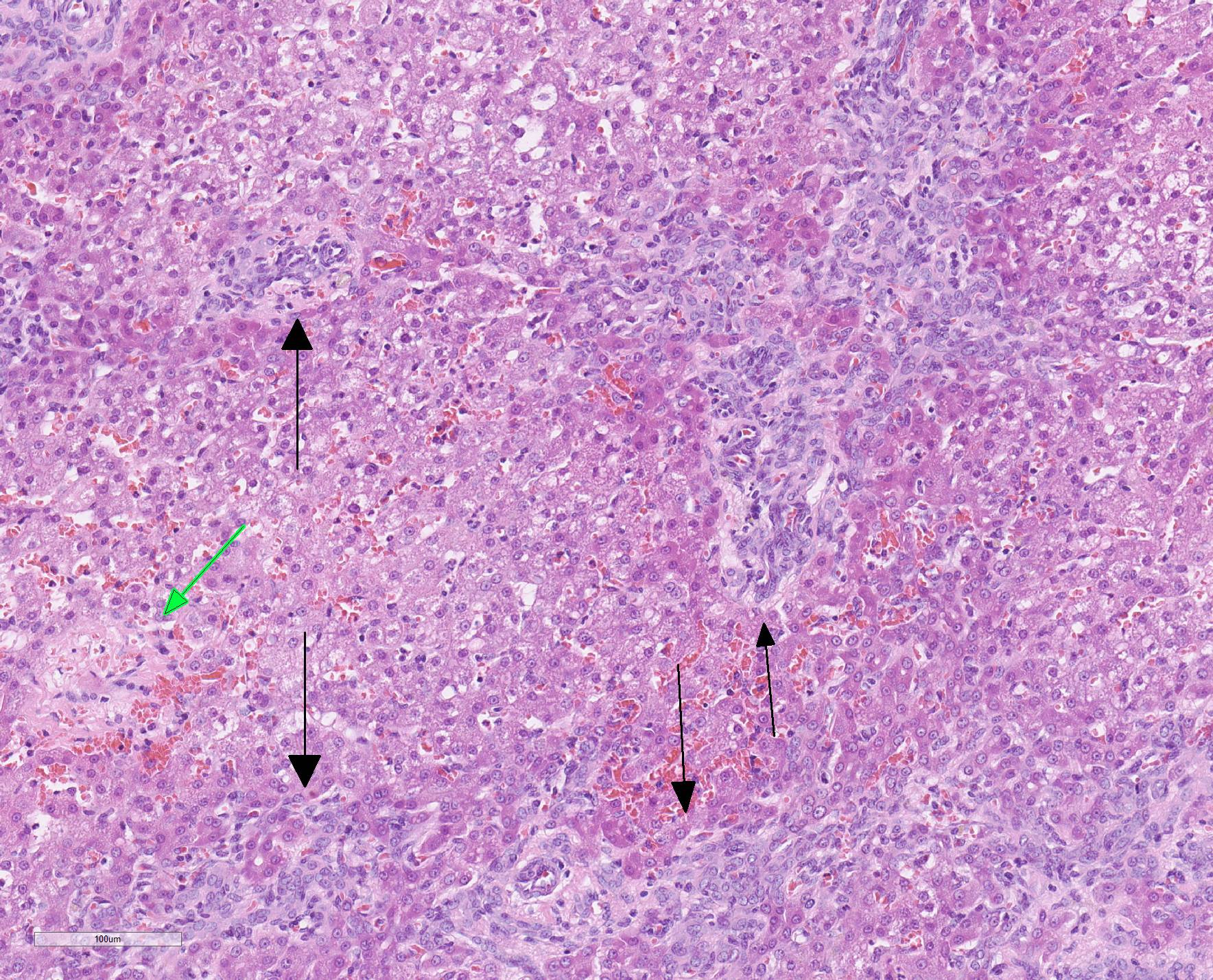

Microscopic Description: Liver, gall bladder: Two sections of liver and gallbladder are examined. Surrounding the common bile duct and gall bladder is a mass-like proliferation of numerous tortuous, small to large, well-differentiated arteries and veins, which rarely anastomose, and dissect or compress the hepatic parenchyma. The endothelium of veins and arteries is occasionally hypertrophied. Arterial and arteriolar walls are diffusely moderately thickened by subintimal edema, pale basophilic, mucinous matrix, and irregular fibers as well as by moderate to marked smooth muscle hypertrophy of the tunica media. The internal elastic lamina is frequently fragmented or absent (confirmed by Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain). The walls of veins and venules are markedly thickened and resemble arteries (arterialization). There is expansion of the tunica intima by irregular fibers and the tunica media by smooth muscle hypertrophy. The lymphatics surrounding the abnormal arteries and veins, those deep to the hepatic capsule, within portal tracts, and surrounding central veins are frequently moderately to markedly ectatic. The adjacent hepatic parenchyma is compressed by the vessels, with multifocal atrophy of the hepatic lobules. Additionally, there are markedly increased numbers of bile duct profiles in portal tracts and isolated within the hepatic parenchyma; these bile ducts are frequently surrounded by concentric lamellar fibrosis (?onion-skinning?) . Portal tracts also have increased numbers of small arteriolar profiles and portal vein profiles are largely absent. Centrilobular hepatocytes are frequently atrophied and diffusely, hepatocytes are mildly to moderately swollen by diaphanous vacuolar change (glycogen type). Scattered throughout the parenchyma are individual necrotic hepatocytes. There is moderate stellate cell hypertrophy; hypertrophied stellate cells frequently contain large, clear, spherical vacuoles (lipid).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver, gallbladder: Arteriovenous fistula with multifocal hepatic compression and atrophy, marked biliary and arteriolar hyperplasia, portal vein hypoperfusion, and moderate, diffuse glycogen-type hepatic vacuolation

Contributor Comment: The diagnostic imaging, gross, and histologic findings of this biopsy sample are consistent with a diagnosis of a hepatic arteriovenous fistula. Arteriovenous (AV) fistulae can be congenital or acquired; acquired AV fistulae are documented to occur following trauma, rupture of arterial aneurysms into a vein, inflammation or necrosis of adjacent vessels, and iatrogenically (typically surgical intervention) 3,5,6. AV fistulae have been reported in a variety of locations, including intrahepatic, pulmonary, and on the limbs.3,6 They have been reported in dogs, cats, horses, cattle, and humans.3,6

Clinical signs of AV fistulae depend on the location; typically signs are associated with increased hydrostatic pressure within veins and subsequent increased intra-lymphatic pressure.3,6 In fistulae involving abnormal blood flow to the liver, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and synthetic liver failure can occur, resulting in depression, seizures, vomiting, and diarrhea. 2,3,6,9,12

Gross findings of AV fistulae usually show one or more anastomoses of a large vein and large artery, surrounded by a tangle of medium and small arteries and venules that contribute to a mass effect. In hepatic arteriovenous fistulae, anastomosis typically involves the portal vein and hepatic artery.2,3,6,9,12 however, there are reports of involvement of the cystic artery in humans.10 Microhepatia is commonly observed due to abnormal portal blood flow. Portal hypertension may result in the development of numerous portocaval acquired shunts.

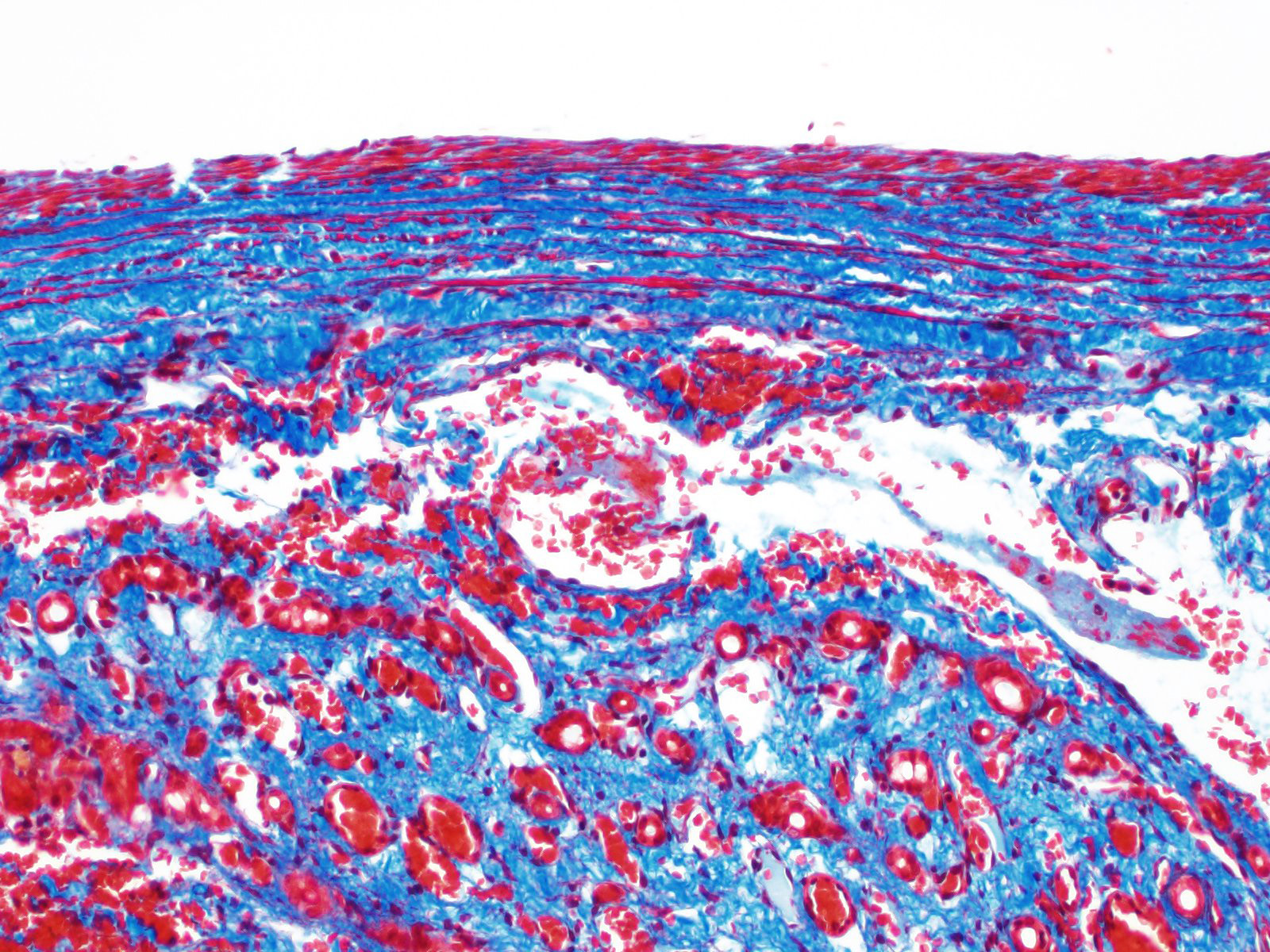

Histology of AV fistulae reveals mass-like proliferations of abnormal arteries and veins, with arterialization of veins. The internal elastic lamina is frequently fragmented, split, or duplicated; in both veins and arteries, the tunica intima is expanded by smooth muscle invasion and hypertrophy, increased deposition of elastin fibers, edema, and mucinous matrix. The tunica media of veins and arteries also exhibits smooth muscle hypertrophy. Additionally, fibrinoid necrosis may be observed. Elastin (Verhoeff-Van Gieson) and trichrome (Gomori?s trichrome) stains highlight the deposition of elastin fibers and fiber fragmentation as well as the fibrosis that often accompanies the fistulae.3,5,6. In fistulae that affect the liver, lesions resembling portocaval shunting occur, including absence or diminution of portal veins, marked biliary and arteriolar proliferation, hepatocyte atrophy, and lymphangiectasia. 2,3,6,9,12 Sinusoids near the fistulae are frequently dilated and congested. Liver lobes away from the fistulae may be normal with little parenchymal change.3

Treatment of AV fistulae is dependent upon location; advanced imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging can facilitate therapeutic intervention. Surgical excision, interventional techniques, and coil embolization have been described in a variety of cases.5,8.

Contributing Institution:

North Carolina State University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Population Health and Pathobiology

https://cvm.ncsu.edu/research/departments/dphp/

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Aberrant arterial connection, focal, severe, with arterial and venous intimal and medial hyperplasia and fibroelastosis, hepatocellular atrophy, congestion, and hemorrhage.

JPC Comment: The contibutor has done an excellent and concise review of arteriovascular fistulae in the dog. Intrahepatic arteriovenous fistulae are most often acquired in humans as a result of surgical intervention, such as hepatic biopsy, transhepatic intervation such as percutaneous cholangiography, surgery or transplantation, and occasionally as a result of trauma. They may also arise within neoplasms (most commonly those which have an endothelial vasoproliferative component, such as infantile hemangiomas).4

In the dog, as in this case, they are likely congenital malformations that often result in portal hypertension as a result of the pressure differential between the hepatic artery and the low-pressure system of the portal circulation. In most affected dogs, large, pulsating vessels on the surface of one or more affected lobes are seen during surgery6; Doppler imaging is a commonly used imaging modality for diagnosis.4,11 As mentioned by the contributor, microhepatia is a common finding in affected dogs, but the affected lobes are enlarged by the presence of the fistulae.6 The WSAVA Liver Standardization group, in their 2006 tome, Standards for Clinical and Histological Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Diseases, put forth their ?strong impression? that arteriovenous fistulas are usually associated with portal vein hypoplasia, based on the observation that recovery from portal hypoperfusion has never been truly recorded following surgical resection of affected lobes.11

This particular case demonstrates the need for special stains for all microscropic evaluation of vascular lesions, and especially arteriovenous fistulae which have significant mural changes. On HE examination, the thickness of the arterial wall can be estimated, and gross disorder of smooth muscle cells can be identified, but much of the fine detail is obvious only after employment of various histochemical stains. A stain for elastin, such as Movat?s pentachrome or Verhoeff-van Gieson, is imperative to identify fragmentation or loss of the internal elastic membrane. Loss of the internal elastic lamina allows migration of smooth muscle cells to the tunica interna, where they may dedifferentiate to a secretory phenotype and engage in arterial wall remodeling by synthesizing extracellular matrix components.1 A stain for collagen, such as a Masson?s trichrome, will demonstrate the amount of collagen within the remodeled intima; and a Movat?s pentachrome will also demostrate excess intercellular elastin fragments as well.

The presence of two sections of liver, one containing sections of the fistula as well as one taken nearby, show significant difference in degree of hepatocellular atrophy. While there is atrophy of hepatocytes in both sections (as is common in dogs with congenital and marked decreases in portal blood flow), there is significant hepatocellular loss in proximity to the fistulae, likely due to compression from the expanded vasculature as well. Examination of the portal triads in the section further away from the fistulae is informative as well, as portal areas contain numerous profiles of hepatic arterioles and bile ductules, but few visible profiles of portal veins. The marked siusoidal dilatation and hemorrhage is the result of the shunting of blood from the hepatic artery into the portal vein, and the generated pressure also results in dilation of lymphatics in both section, most prominently and strikingly around the sublobular veins (the so-called "rose window"effect, per personal communication, Dr. John Cullen.

The

moderator adeptly summarized the changes in the slide by stating that "when you

see arteries looking like veins and veins looking like arteries, you must add

arteriovenous fistula or malformation to your differential diagnosis". The

moderator noted another particular histologic finding in this section in the

walls of hypertrophic arterioles ? the apparent formation of two distinct

layers of smooth muscle, oriented perpendicularly to each other ? not a

specific finding , but an indication of arterial wall disease.

The moderator opined that in the diagnosis of arteriovenous malformations,

imagining is the gold standard, and hopefully the histology is supportive ?

diagnosis solely on histology may be problematic. The participants discussed

the difference between arteriovenous "fistula" and "malformation".

Arteriovenous fistulas are composed of a single connection between arteries and

veins and the histologic findings may be more obvious on histology; artiovenous

malformastions are multiple connections often formin a niduls of connections

which may or many not be as easily discerned on histology.

Finally, the discusion of chronic congestion versus hemorrhage, which obscured much of the hepatic parenchyma on the slide was determined to be complicated by the fact that this sample was a biopsy.

References:

1. Aiello VD, Gutierrez PS, Chaves MJF, Lopes AAB, Higuchi ML, Ramires JAF. Morphology of the Internal Elastic lamina in arteries from pulmonary hypertensive patients: a conocal laser microscopy study. Mod Pathol 2003; 16(5):411-416.

2. Booler, H. Congenital Intrahepatic Vascular Anomaly in a Clinically Normal Laboratory Beagle. Tox Path. 2008, 36: 981-984

3. Cullen, JC and Stalker, MJ. Liver and Biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 4th Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016. 266.

4. Gallego C, Miralles M, Marin C, Muyor P, Gonzalez G, Garcia-Hidalgo E. Congenital hepatic shunts. RadioGraphics 2004; 24:755-772.

5. Leach, S.B., Fine, DM., Schutrumph, RJ., Britt, LG., Durham, HE., Christiansen, K. Coil embolization of an aorticopulmonary fistula in a dog. J Vet Cardiol. 2010; 12: 211-216.

6. Moore, P. F. and Whiting, P. G. Hepatic lesions associated with intrahepatic arterioportal fistulae in dogs. Vet Path. 1986; 23 (1): 57-62.

7. Robinson, WF and Robinson, NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 4th Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016. 56.

8. Saunders, AB., Fabrick, C., Achen, SE., Miller, MW. Coil embolization of a congenital arteriovenous fistula of the saphenous artery in a dog. J Vet Intern Med. 2009; 23: 664-664.

9. Schaeffer, IGF., et al. Hepatic arteriovenous fistulae and portal vein hypoplasia in a Labrador retriever. JSAP. 2001; 42: 146-150.

10. Tajima, H., Hosaka, J., Tajma, N., Kumazaki, T. Arteriovenous malformation of the gallbladder. Eur. Radiol. 1997; 7: 333-334.

11. Rothuizen J, Bunch SE, Charles JA, Cullen JM, Desmet VJ, Szatmari V, Twedt DC, van den Ingh TSGAM, Ven Winkle T, Washabau RJ. Morphological classification of circulatory disorders of the canine and feline liver. . In: WSAVA Standards for Cinical and Histological Diagnosi of Canine and Feine Liver Disease. Edinburgh, Saunders-Elsevier, 2006, pp 53-55.

12. Yoshizawa, K., Oishi, Y., Matsumoto, M., Fukuhara, Y., Makino, N., Noto, T. Fujii, T. Congenital Intrahepatic arteriovenous fistulae in a young beagle dog. Tox Path. 1997; 25: 495-499.