Signalment:

Gross Description:

All other organs including liver and spleen were considered to be grossly within normal limits.

Histopathologic Description:

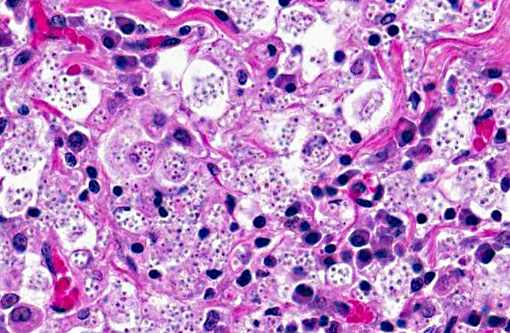

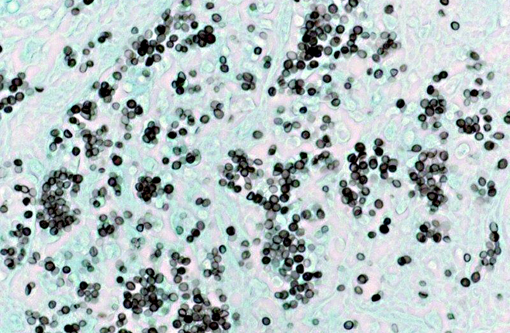

The tracheobronchial lymph nodes (not submitted) were expanded by sheets of epithelioid macrophages, many of which contained similar yeast bodies. Organisms were further demonstrated by Gomori methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff on lung and lymph node. Fewer, scattered macrophages with intracellular yeasts were identified in the liver and spleen with special stains.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Inoculation is by inhalation of spores from contaminated soil. The spores are then taken up by pulmonary macrophages and spread to local lymph nodes and, often, throughout the body. Respiratory disease is most common, but the frequency of gastrointestinal lesions in animals suggests that oral inoculation is also possible.(7) Localized infections in the skin and eye are also reported(1); disseminated disease is invariably fatal. Clinical signs include fever, malaise and respiratory distress; hepatic and splenic enlargement are present if the disease is disseminated. Debilitated patients are often anemic and maybe be terminally leukopenic.(7) Gross lesions are dependent upon the extent of dissemination in the body. The lesions illustrated in the lungs and lymph nodes of this cat are a classic presentation of the respiratory lesions of histoplasmosis in cats.(1,2) Histologically, the organisms are easily distinguished from other dimorphic fungi (Cryptococcus neoformans, Blastomyces dermatitidis and Coccidioides immitis) by their size and obligate intracellular location.

The pathogenesis of the disease is best characterized in people.(3) Once phagocytized by pulmonary macrophages, the conidia convert to the yeast form and disseminate within the reticuloendothelial system. Dendritic cells present antigen to T lymphocytes and within 2-3 weeks, cell mediated immune responses stimulate cytokine dependent killing of yeast by effector macrophages. In the absence of effective cell-mediated immunity (as in HIV-AIDS patients), fungus disseminates and leads to terminal illness. In the immunocompetent human host infections are most often inapparent, with occasional acute or chronic localized manifestations.(5) Localized chronic pulmonary infections are often mistaken clinically for neoplasia. The pathogenetic factors that determine inapparent and clinical disease in animals is less well characterized, but presumably involves similar cell mediated immune mechanisms.(7)

Diagnosis can be made by fine needle aspirates or impression smears, confirmed by histopathology and may be verified by culture or PCR. Fungal culture, however, is a risk to laboratory personnel, as the chlamydospores of the mycelial phase are highly infective.(7)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | Coccidioides immitis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Histoplasma farciminosum | Sporothrix schenckii | Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Disease | Blastomycosis | Coccidioidomycosis | Histoplasmosis | Epizootic lymphangitis | Sporotrichosis | Cryptococcosis |

| Species most affected | Dogs, humans | Dogs, horses, cats, humans | Dogs, cats, humans | Horses | Horses, cats, dogs, humans | Cats, horses, humans |

| Organs affected | Lungs, skin, metastasis to other tissues | Lungs, metastasis to bones, skin, and other tissues | Lungs, metastasis to other organs | Skin, lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes | Skin, lymphatic vessels | Nasal cavity, lungs, brain, eye, skin |

| Tissue morphology | Large (8 to 10 μm), broad-based unipolar budding yeast cells | Large (10 to 80 μm) spherules with numerous 2 to 5 μm endospores | Small (1 to 5 μm) narrow base budding yeast cells *var. duboisii are larger (5 to 20 μm) | Small (1 to 5 μm) narrow base budding yeast cells | Small (2 to 5 μm) narrow base budding yeast cells | Small (4 to 8 μm) narrow base budding, thick-walled yeast surrounded by a large 5 to 10 μm gelatinous capsule |

References:

2. Kabali S, Koschmann JR, Robertstad GW, et al. Endemic canine and feline histoplasmosis in El Paso, Texas. J Med and Vet Mycol. 1986;24:41-50.

3. Knox KS, Hage CA. Histoplasmosis. Proc Am Thoracic Soc. 2010;7:169-172.

4. Quinn PJ, et al. Actinobacteria. In: Veterinary Microbology and Microbial Disease. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Wiley Blackwell; 2011, Kindle edition, location 17002 of 35051.

5. McKinsey DS, McKinsey JP. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Sem in Resp and Critical Care Med. 2011;32:735-744.

6. University of Adelaide Mycology Online. Dimorphic Systemic Mycoses, http://www.mycology.adelaide.edu.au/Mycoses/Dimorphic_systemic /. Accessed online on 28 March 2013.Â

7. Valli VEO. The hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2007:299-301.