Signalment:

10-year-old, neutered male, orange tabby cat (

Felis catus)Generalized edema that progressed to extremities. Euthanized.

Gross Description:

Red to gold, serous fluid with crepitus and occasional fibrin tags extends the

subcutaneous tissues of the entire body with the exception of the head. The legs and feet are edematous

and swollen due to the subcutaneous fluid. The thoracic cavity contains approximately 25 ml of clear

orange to pink serous fluid (specific gravity 1.022).

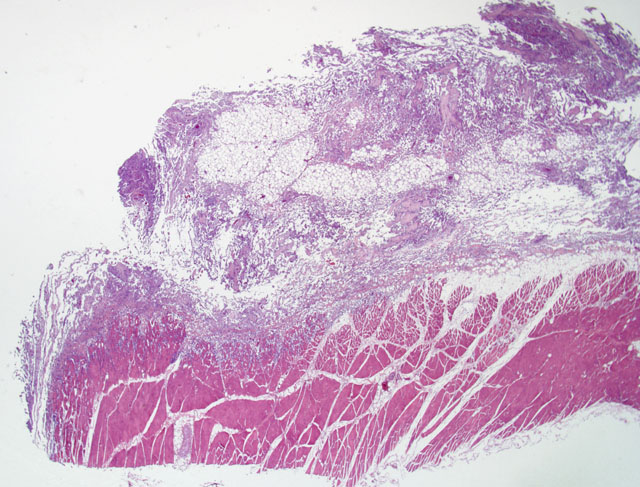

Histopathologic Description:

Diffusely expanding the subcutis and multifocally infiltrating the musculature is a non-encapsulated, poorly demarcated, moderately cellular neoplasm that forms numerous clefts and variably formed channels supported by a collagenous and fibrous stroma. Cells have distinct cell borders, and are pleomorphic to spindloid. There is scant to moderate amounts of amphophilic, finely granular cytoplasm, round to oval basophilic nuclei, and finely stippled chromatin with an occasional single

magenta nucleolus. There are rare mitotic figures. Moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are present. Channels are filled with variable numbers of erythrocytes. There are scattered lymphohistiocytic infiltrates, multifocal areas of hemorrhage, edema, and myocyte degeneration.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Subcutis: Feline ventral abdominal angiosarcoma

Lab Results:

Immunohistochemistry Greater than 90% of neoplastic cells had strong to weak,

diffuse, intracytoplasmic labeling with both CD31 and Factor VIII markers.

Condition:

Feline ventral abdominal angiosarcoma

Contributor Comment:

Feline abdominal angiosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor of vascular

endothelial origin, which typically only occurs in the dermis and subcutis of cats. Controversy exists as to

whether the endothelial cell proliferation is of lymphatic or blood vessel origin.(2,3) The term

angiosarcoma is used to avoid this confusion. Although a palpable distinct mass is usually not discernible,

the neoplasm may vary in texture from gelatinous and soft to hard.(2,3) Grossly, the cut surface of the

lesion may appear to have red or black discoloration and seep serosanguineous fluid.(2,3) However, in this

case widespread edema with occasional fibrin tags was the only clinical sign. There was no discernable

mass. Typically, a preliminary diagnosis is established on anatomical location, clinical history, gross

appearance, and histological features. Immunohistochemistry may be used to confirm the endothelial

origin of the tumor using a CD31 and factor VIII antibody staining protocol.(3,4) Our case was positive for

both CD31 and factor VIII. Although metastasis is rare, the prognosis is poor due to its extensive

infiltrative growth and frequent recurrences.(2,3,6) The only recognized treatment is repeated surgical

excision.(2) Hemangiosarcomas have also been reported in the cow, horse, pig, goat, and sheep.(4,8)

JPC Diagnosis:

Fibro-adipose tissue and skeletal muscle: Feline ventral abdominal angiosarcoma

Conference Comment:

The contributor's comments accurately and concisely give a general overview of

feline ventral abdominal angiosarcoma.

As noted by the contributor, there is controversy whether this neoplasm arises from blood capillary

endothelium or lymphatic endothelium. Immunohistochemical staining for lymphatic vessel endothelial

receptor-1 (LYVE-1), a marker unique to lymphatic endothelial cells, and the ultrastructural features are

strong evidence that these neoplasms are of lymphatic origin.(1) The term -Ç-ÿfeline abdominal

lymphangiosarcoma has been proposed.(1) These tumors form vascular clefts and cavernous channels

supported by collagenous connective tissue.(5) A papilliferous growth pattern was noted in 11 of 12 cases

in a retrospective study, with multifocal areas containing fusiform and polygonal cells densely packed

together.(5) Differentials for this neoplasm include lymphangiomatosis and hemangiosarcoma.

Pleomorphic lymphatic endothelial cells lining vascular channels as well as blind ending trabeculae and a

very aggressive, invasive growth pattern separate this neoplasm from lymphangiomatosis, which is

considered a developmental disorder wherein the lymphatic system does not form proper communicating

channels with the venous system.(3) Electron microscopy is useful in differentiating lymphangiosarcoma

and hemangiosarcoma. Ultrastructurally, lymphatic vessels have a discontinuous basement membrane,

while hemangiosarcomas have an uninterrupted basement membrane.(3) Useful immunohistochemical

stains for lymphangiosarcoma include lymphatic vessel endothelial receptor-1 (LYVE-1), vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor -3 (VEGFR-3), and podoplanin because they are purportedly markers

unique for lymphatic endothelial cells.(1)

References:

1. Galeotti F, Barzagli F, Vercelli A, Millanta F, Polil A, Jackson DG, Abramo F: Feline

lymphangiosarcoma definitive identification using a lymphatic vascular marker. Vet Dermatol 15:13-18,

2004

2. Goldschmidt MH, Hendrick MJ: Tumors of Skin and Soft Tissues. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed.

Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp.102-103. Blackwell Publishing Company, Ames, IA, 2002

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK: Mesenchymal Neoplasms and Other Tumors. In: Skin

Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 748-756. Blackwell Publishing Company, Ames, IA, 2005

4. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM: Skin and Appendages. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed.

Maxie MG, 5th ed., pp. 767-768. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

5. Hinrichs U, Puhl S, Rutteman GR, Van Der Linde-Sipman JS, Van Den Ingh TSGAM:

Lymphangiosarcomas in cats: a retrospective study of 12 cases. Vet Pathol 36: 164-167, 1999

6. Johannes CM, Henry CJ, Turnquist SE, et al: Hemangiosarcoma in cats: 53 cases (1992-2002). J Am

Vet Med Assoc 231(12): 1851-6, 2007

7. McAbee KP, Ludwig LL, Bergman PJ, Newman SJ: Feline cutaneous hemangiosarcoma: a retrospective

study of 18 cases (1998-2003). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 41(2):110-6, 2005

8. Schultheiss, PC: A retrospective study of visceral and nonvisceral hemangiosarcoma and hemangiomas

in domestic animals. J Vet Diagn Invest 16:522-526, 2004