Signalment:

Ultrasound revealed a distended bladder; the uterus was distended with fluid in both horns. Pyometra was considered but hemogram and serum biochemical analyses were normal, except for a mild serum globulin concentration. Radiographs showed no pulmonary involvement.

Clinical pathology findings at this time: Low positive Lyme titer. CBC profile: HTC 40.3 (37-55 %); WBC 14.38 (6.5-15.90 th/ul); & neutrophils 80, lm 5%, mono 12 % eos 3 %. Mild moderate platelet clumping.

BUN creatitine within normal limits.

Total protein 8.6 (5.2-8.2)

Albumin 2.9 (2.5-4)

Globulin 5.7 (2.5-4.5)

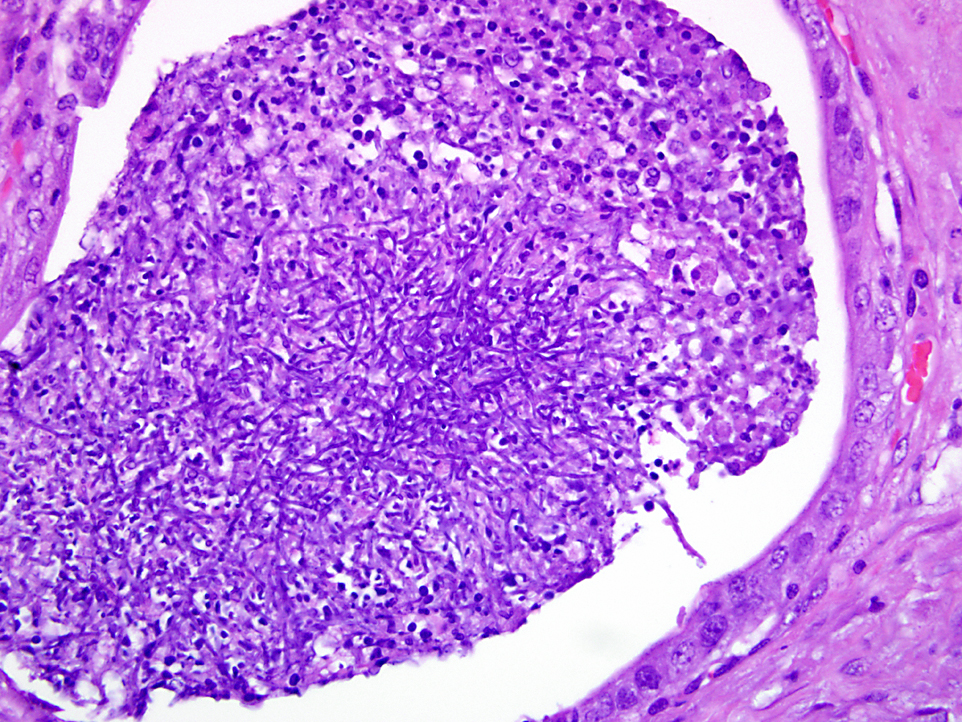

Two days after the animals initial visit she was walking sideways, not defecating, and falling down. The animal had a mild head tilt to the left, walked in circles, and bilateral nystagmus. Vestibular disease, Lyme disease and Leptospirosis were included in the differential diagnosis. The dog was treated with tetracycline. The owner wanted an ovariohystorectomy performed on the animal. Cytology performed during surgery revealed numerous degenerated neutrophils and long thin septated fungal hyphae. The animal started fluconazol therapy. The owner was advised of the cytology findings and the owner decided on euthanasia 3 days after surgery. The animal collapsed just before arriving to the clinic and arrived unconscious. The animal was euthanized.

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Bulbithecium spp. (closely related to Bulbithecium hyalosporium) was isolated.Â

The anomorph of this fungus is Acremonium spp.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The classification of Acremonium spp. has changed; previously it was described as hypomycetes, and currently it is classified as one of the two members under the group Dykara in the sub group Ascomycotas. It is still classified as Imperfect fungi (Deuteromycota), and nondematiaceous (not pigmented), but the term hyphomycetes is obsolete.

Pyometra is inflammation of the uterus that has variable symptomology from genitourinary disease to non-specific systemic disease. In the dog, pyometra is associated with cystic endometrial hyperplasia predisposed for by luteal activity (progesterone). During this phase, progesterone inhibits the intrauterine leukocyte response, decreases muscle contractibility and stimulates development and secretion of endometrial glands.(2,8) Clinically, pyometra can be associated with or without vaginal discharge depending on whether the cervix is closed or open. If the cervix is closed, the prognosis is more serious since the possibility of septic or uterine peritonitis exists.(2,9)

Fungi are a very variable group of eukaryotic organisms that belong to the fungi kingdom.(7) The old classification was based on morphologic microscopic features that classified the kingdom in 6 phyla. Classification of fungi is confusing and based on several criteria including formation of hyphae, pseudohyphae, or yeast forms. Another feature important in classification is the presence of a sexual stage of reproduction (teleomorph stage) or the absence of sexual reproduction (anamorphous stage). Biochemical and physical properties can be used to distinguish different species. However, more recently, molecular genetics and DNA analysis have played a role in taxonomy.(7)

Unfortunately, at the present time, there are no agreements on specific rules for an international system to facilitate the fungal nomenclature. There are some efforts to create an organized fungal classification scheme.(7)

The kingdom of Fungi is classified in 7 or 8 phyla or subdivisions.(5)

| Species (examples) | ||||

| I | Microsporidia | Unicellular parasites | ||

| II | Chytridiomycota | presence of a flagella | Protists-?? | |

| III | Blastocladiomycota | saprotrophs | ||

| IV | Ascomycota | Yeast, septate hyphae and/or pseudohyphae Septate hyphae Yeast or filamentous morphology. Imperfect fungi= Deuteromycota | Perfect fungi Sexual spores = ASCOSPORES Imperfect fungi No sexual spores | Histoplasma, Pichia, Candida, Aspergillus, Cladosporidium, Alternaria Sacharomyces |

| V | Basidiomycota | Imperfect fungi = Deuteromycota | Imperfect fungi No sexual spores | Cryptococcus Malassezia |

| VI | Neocallimastigomycota | Anaerobic organisms | Perfect fungi Sexual spores = BASIDIOSPORES | |

| VII | Glomeromycota | Perfect fungi Sexual spores = ZYGOSPORES Zygomycota | Perfect fungi Sexual spores = ZYGOSPORES. Non-septate hyphae | Mucor,Rhizopus Absidia Mortierella |

| VIII | Oomycota | Cellulose-walled fungi-like- organims | Pythium, Saprolignea | |

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In mares, a reported fungal cause of abortion is fescue grass toxicity caused by Neotyphodium (formerly Acremonium) coenophialum. This fungal endophyte infects grass and produces the ergot alkaloid ergovaline, which causes dysmaturation of foals and infrequent abortion. Ergovaline, in addition to its well known alpha-2 adrenergic agonistic effects causing vasoconstriction seen in fescue foot in cattle, is a potent dopamine D2 receptor agonist which blocks prolactin, which is important in maintaining the corpus luteum and mammary gland growth and milk production. The lack of prolactin with decreased progesterone and increased estradiol in the mare during pregnancy can lead to fetal death. Fetal death also occurs from suffocation due to a thick edematous placenta that does not rupture at the cervical star. The mares are also agalactic with minimal colostrum, and if the foal survives to term, they often die due to failure of passive transfer.Â

References:

2. Bonagura JD, Kirk RW. Kirks Current Veterinary Therapy XII, Small Animal Practice. W.B. Saunders Co; 1995.Â

3. Bruchim Y, Elad D, Klainbart S. Disseminated aspergillosis in two dogs in Israel. Mycoses. 2006;49(2):130-3.

4. Day MJ, Eger CE, Shaw SE, Penhale WJ. Immunologic study of systemic aspergillosis in German shepherd dogs. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1985;9(4):335-347.

5. Deacon, JW. Modern Mycology 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 1997.

6. Foley JE, Norris CR, Jang SS. Paecilomycosis in Dogs and Horses and a Review of the Literature. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2002;16(3):238-243.Â

7. Hibbett DS, et al. A higher level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycological Research. 2007;111(5):50947.

8. McGavin DM. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease 4th ed. Mosby/Elsevier; 2007.Â

9. Noakes DE, Dhaliwal GK, England GC. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia/pyometra in dogs: a review of the causes and pathogenesis. J Reprod Fertil. 2001;57 (Suppl):395-406.

10. Pedersen NC. A review of immunologic diseases of the dog. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1999;69 (2-4):251-342.

11. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:537-8.

12. Simpson KW, Khan KN, Podell M, et al. Systemic mycosis caused by Acremonium sp in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;203(9):1296-9.