WSC 2022-2023

Conference 25

Case IV:

Signalment:

4.8-years-old, female, Limousin, (Bos taurus) bovine.

History:

Presented to the Institute of Veterinary Pathology with a history of thickened skin, hypotrichia, alopecia and signs of lameness.

Gross Pathology:

The skin displayed generalized thickening with folding and wrinkling. The peripheral lymph nodes were enlarged. Multiple white miliary foci were disseminated in the respiratory and vaginal mucosa, fasciae and scleral conjunctivae. The claws revealed rotation of the distal phalanges.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

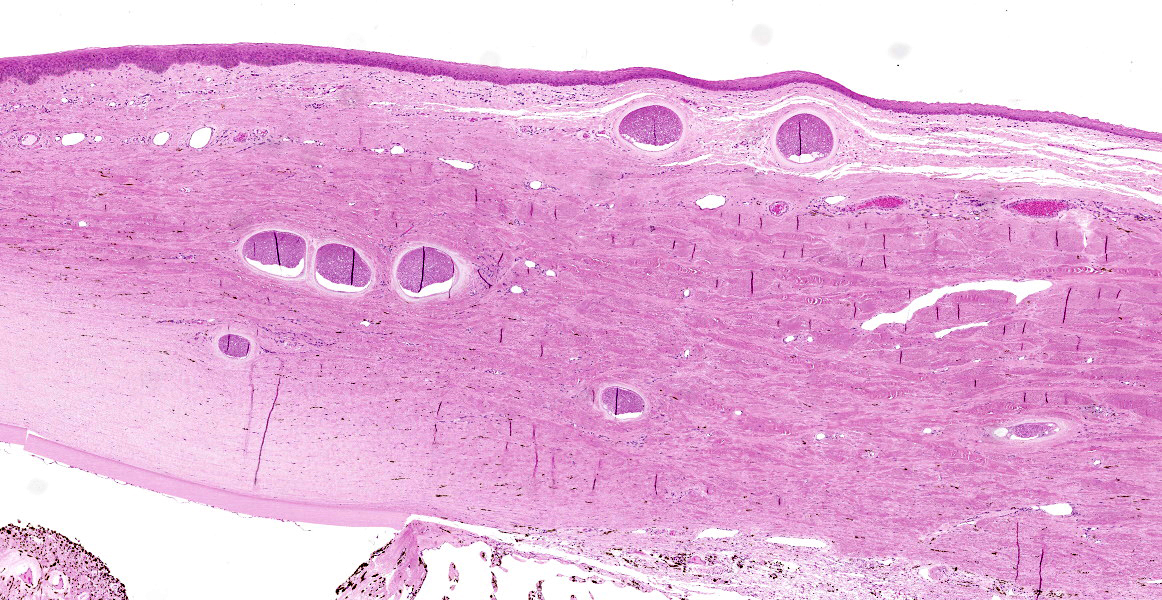

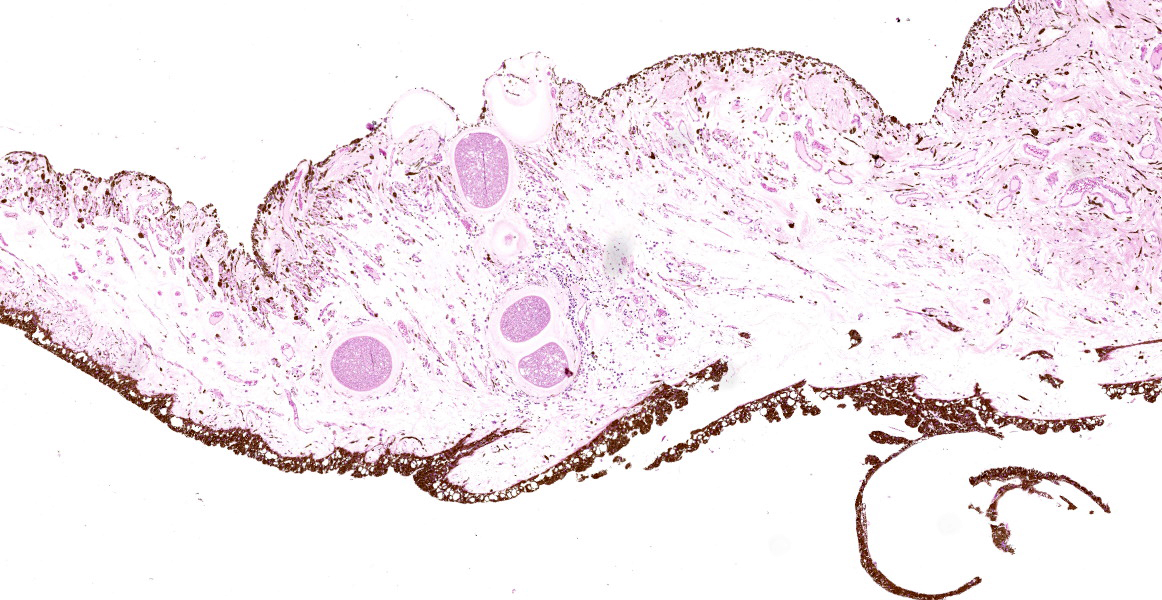

Microscopic Description:

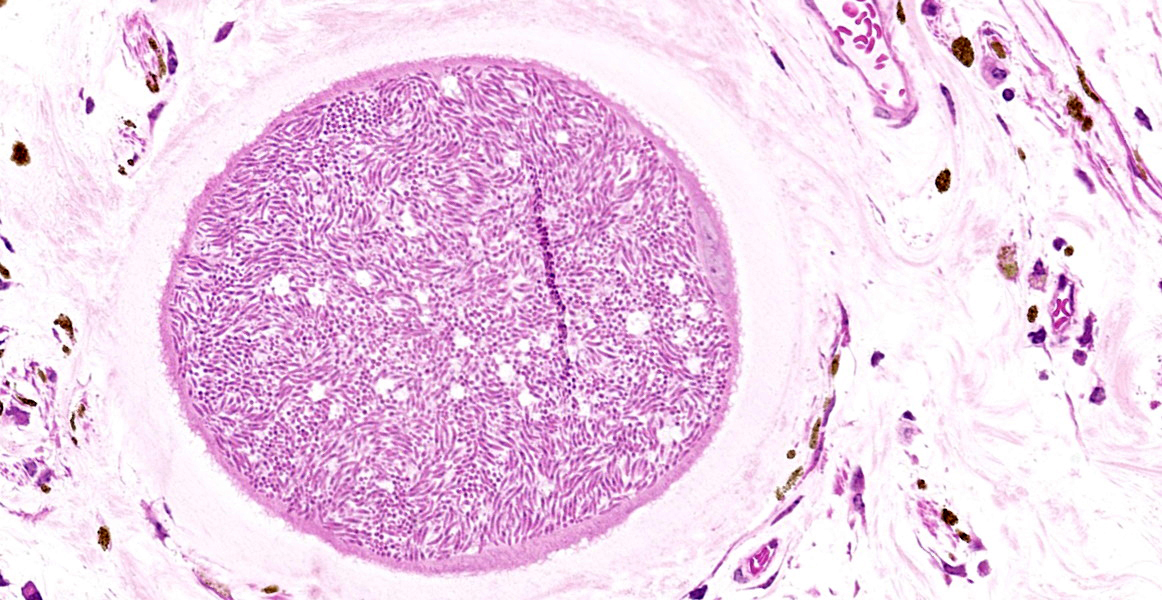

Eye (anterior part): Multifocal expansion and bulging of the conjunctiva, iris and sclera by many interstitial mature protozoal cysts. The multi-layered protozoal tissue cysts are 150-350 µm in diameter with an outermost 15-30 µm pale eosinophilic, hyaline capsule. Next is a greenish intermediate layer (5 µm, not in all cysts), followed by a 5-15 µm rim of host cell cytoplasm containing 2-5 giant but flattened nuclei. The majority of the cyst is composed of the central parasitophorous vacuole containing numerous, tightly packed, crescent-shaped, 2x7 µm bradyzoites. Occasionally, a thin concentric layer of spindle-shaped cells with flattened nuclei (fibrocytes) and eosinophilic fibers (mature

collagen) surrounds cysts. Some cysts are concentrically surrounded by small to moderate numbers of macrophages, multi-nucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and fewer plasma cells and eosinophils. Occasionally, cysts are directly beneath and bulging iridal anterior and posterior pigment layers and corneal endothelium (not on all slides).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Eye: Conjunctivitis and iritis, multifocal, granulomatous, mild, chronic with intralesional protozoal cysts.

Cause: Besnoitia besnoiti

Etiologic diagnosis: Protozoal conjunctivitis

|

Table 4.1 |

|||

|

Species |

Target organs |

Intermediate host |

Definitive host |

|

B. akodoni |

Internal organs |

Grass mouse |

Unknown |

|

B. bennetti |

Non-intestinal mucosa, skin, SC |

Donkey, burro, horse, mule |

Unknown |

|

B. besnoiti |

Non-intestinal mucosa, skin, SC |

Cattle, wild ungulates, antelopes |

Unknown |

|

B. caprae |

Non-intestinal mucosa, skin, SC |

Goat, sheep |

Unknown |

|

B. darlingi |

Ear, internal organs, SC |

Virginia opossum, (lizard) |

Cat, bobcat |

|

B. jellisoni |

Internal organs |

Deer mouse |

Unknown |

|

B. neotomofelis |

Internal organs |

Woodrat |

Cat |

|

B. oryctofelisi |

Internal organs, muscle |

Rabbit |

Cat |

|

B. tarandi |

Non-intestinal mucosa, skin, SC |

Caribou, reindeer, mule deer, muskox |

Unknown |

|

B. wallacei |

Internal organs |

Rat |

Cat |

Contributor’s Comment:

Bovine besnoitiosis is a chronic debilitating disease of cattle, caused by the cyst-forming apicomplexan parasite Besnoitia besnoiti. The disease is re-emerging in Europe and showed rapid spread to Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Hungary, Belgium, and Ireland within eight years.11 The genus Besnoitia has 10 species (Table 4.1).6B. besnoiti, the type species mainly affects cattle, and wild ungulates may represent a natural reservoir of infection.10 The life cycle of bovine besnoitiosis is incompletely understood. Cattle represent intermediate hosts, where cyst-formation takes place but the definitive hosts, where intestinal sexual reproduction is thought to occur are unknown. In analogy to the four species with complete knowledge of life cycle (B. darling, B. neotomofelis, B. oryctofelisi, B. wallacei) a heteroxenous life cycle is assumed.

In cattle, acute besnoitiosis is characterized by fast proliferation of tachyzoites in endothelial cells and cells of macrophage lineage. Clinical signs include pyrexia, anorexia, nasal and ocular discharge, peripheral lymphadenopathy, lameness and subcutaneous edema. Histological alterations in this stage consist of microcirculatory and vascular lesions like vasculitis, thrombosis, hemorrhage, and edema. Tachyzoites are few in naturally acquired bovine besnoitiosis and are difficult to identify in FFPE-tissues.1,10

In the chronic stage, pathognomonic parasitic cysts develop in various tissues. Preferentially affected are non-intestinal mucosa, scleral conjunctiva, skin and fasciae. For unknown reasons and in contrast to peripheral tissues, visceral organs harbor markedly reduced parasite load. Severe chronic bovine besnoitiosis leads to thickening and wrinkling of the skin, sole ulcers and - in bulls - orchitis and sterility.3,6,13,14 Cysts consist of a central, cytoplasmic, single-membraned parasitophorous vacuole harboring numerous slow-replicating bradyzoites. The host cell cytoplasm surrounding the parasitophorous vacuole is usually thin and contains several enlarged, but flattened hots cell nuclei. The next layer (intermediate layer, inner cyst wall) is not present in every mature cyst but is readily visible in developing cysts. The outermost layer of the cyst is a pale-eosinophilic, hyaline layer, consisting of interwoven collagen fibrils.13 The host cell of B. besnoiti is immunohistochemically positive for vimentin and smooth muscle actin suggesting myofibroblast origin.5 Usually, at least some cysts are surrounded by pericystic inflammation, which mainly consists of T-cells, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells and eosinophils. Destruction of cysts is evident in subacute and chronic cases.14

In animals with obvious lesions, the diagnosis is made via clinical findings and histology. Because most of the chronic cases are mildly clinical or subclinical, diagnosis of bovine besnoitiosis on the herd level requires serology and/or PCR.7,18,19 Epidemiology of bovine besnoitiosis is incompletely understood. Animals are infected via direct contact, biting arthropods or mechanical vectors. Transmission occurs mainly in the summer months when insect activity is high. In endemically infected herds, there is variable seasonal serological and clinical incidence and prevalence.9,10

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Veterinary Pathology

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

LMU Munich

Veterinaerstr. 13

80539 Muenchen

http://www.patho.vetmed.uni-muenchen.de/index.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Eye, conjunctiva, sclera, and iris: Multiple apicomplexan cysts.

JPC Comment:

This represents a classic case of ocular Besnoitia in a cow, and this protozoa produces characteristic cysts which can reach up to 5 mm in diameter and are visible on gross examination. Protozoal cysts appear as small white nodules on the haired skin of the face, ears, scrotum, and conjunctiva, where they are called scleral pearls.2 Other classic signs of chronic B. besnoiti infection include alopecia, thickening, and wrinkling of the periocular skin, the scrotum, and other areas of the body due to scleroderma.17 Gross differentials for the skin lesions include dermatophytosis and photosensitization, both of which can cause blepharitis, and Moraxella bovis and Listeria monocytogenes, both of which are important causes of conjunctivitis in cattle. None of these differentials would have pearlescent nodules.3

The acute phase of Besnoitia infection has less specific clinical signs (i.e. fever), lasts less than a month, and often goes undetected. The underlying lesion is vasculitis and thrombosis of small caliber vessels, which some authors have speculated is due to replication of tachyzoites within endothelial cells.17 The acute phase may result in death due to nephrotic syndrome or respiratory distress.17 A recent review article found that bulls are likely more susceptible than females to infection, and in the acute phase they can develop significant orchitis and infertility.17

This review article also found that infection of animals less than 6 months of age is rare, and that the incidence of infection increased with advancing age.17

Besnoitia is an economically important disease in many areas of the world. Most cases are subclinical or have scleral cysts as the only clinical sign. When infection is introduced into a naïve herd, it is expected that 10% to 50% of animals will develop clinical signs and lose economic value within the next three years.17 In endemically infected herds, the proportion of animals showing clinical signs is expected to increase with time.17 A recently developed modified live vaccine controls clinical signs but does not appear to be effective in preventing subclinical infection.17

Some of the conference participants described the vacuolation of the corneal endothelium in this section as a pathologic change; the moderator, who has a special interest in ocular pathology, explained that this is a normal and expected finding. Unless coupled with attenuation or other corroborating evidence, it should not be considered abnormal.

The moderator discussed other protozoa which can be found in the eye, including Trypanosoma, Toxoplasma, Leishmania (25% of systemic cases involve the eye), and Neospora caninum; Encephalitozooncuniculi can also cause phaecoclastic uveitis in rabbits.

References:

- Basson PA, McCully RM, Bigalke RD. Observations on the pathogenesis of bovine and antelope strains of Besnoitia besnoiti (Marotel, 1912) infection in cattle and rabbits. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1970;37(2): 105-126.

- Bowman DD. Protists. In: Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2021; 116.

- Buergelt CD, Clark EG, Del Piero F. Bovine Pathology. Boston, MA: CABI. 2017: 371-372.

- Cortes H, Leitao A, Vidal R, et al. Besnoitiosis in bulls in Portugal. Vet Rec. 2005;157(9): 262-264.

- Dubey JP, Wilpe E, Blignaut DJC, Schares G, Williams JH. Development of early tissue cysts and associated pathology of Besnoitia besnoiti in a naturally infected bull (Bos taurus) from South Africa. J Parasitol. 2013;99(3): 459-466.

- Dubey JP, Yabsley MJ. Besnoitia neotomofelis sp. (Protozoa: Apicomplexa) from the southern plains woodrat (Neotoma micropus). Parasitology. 2010;137(12): 1731-1747.

- García-Lunar P, Ortega-Mora LM, Schares G, Diezma-Díaz C, Álvarez-García G. A new lyophilized tachyzoite based ELISA to diagnose Besnoitia infection in bovids and wild ruminants improves specificity. Vet Parasitol. 2017;244: 176-182.

- Gollnick NS, Scharr JC, Schares G, Langenmayer MC. Natural Besnoitia besnoiti infections in cattle: chronology of disease progression. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:

- Gollnick NS, Scharr JC, Schares S, Barwald A, Schares G, Langenmayer MC. Naturally acquired bovine besnoitiosis: Disease frequency, risk and outcome in an endemically infected beef herd. Transbound Emerg Dis.

- Gutierrez-Exposito D, Arnal MC, Martinez-Duran D, et al. The role of wild ruminants as reservoirs of Besnoitia besnoiti infection in cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2016;223: 7-13.

- Gutiérrez-Expósito D, Ferre I, Ortega-Mora LM, Álvarez-García G. Advances in the diagnosis of bovine besnoitiosis: current options and applications for control. Int J Parasitol. 2017;47(12): 737-751.

- Gutiérrez-Expósito D, Ortega-Mora LM, García-Lunar P, et al. Clinical and serological dynamics of Besnoitia besnoiti infection in three endemically infected beef cattle herds. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(2): 538-546.

- Kumi-Diaka J, Wilson S, Sanusi A, Njoku CE, Osori DI. Bovine besnoitiosis and its effect on the male reproductive system. 1981;16(5): 523-530.

- Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Majzoub-Altweck M, Scharr JC, Schares G, Hermanns W. Naturally acquired bovine besnoitiosis: histological and immunohistochemical findings in acute, subacute, and chronic disease. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(3): 476-488.

- Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Scharr JC, et al. Besnoitia besnoiti infection in cattle and mice: ultrastructural pathology in acute and chronic besnoitiosis. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(3): 955-963.

- Lucio-Forster A, Lejeune M. Diagnostic Parasitology. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2021: 443.

- Malatji PM, Tembe D, Mukaratirwa S. An update on epidemiology and clinical aspects of besnoitiosis in livestock and wildlife in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2023; 21:e00284.

- Schares G, Langenmayer MC, Scharr JC, et al. Novel tools for the diagnosis and differentiation of acute and chronic bovine besnoitiosis. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43(2): 143-154.

- Schares G, Maksimov A, Basso W, et al. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction assays for the sensitive detection of Besnoitia besnoiti infection in cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2011;178(3-4): 208-216.