Signalment:

20-year-old Arabian mare (

Equus caballus).The mare was presented obtunded and icteric with prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial

thromboplastin time (PTT) and markedly elevated liver enzymes (GGT, AST), ammonia, bilirubin and bile acids.

The animal received tetanus antitoxin soon after she foaled approximately 60 days prior to presentation. She was

anorexic and had lost weight for about a month. The mare was treated with fluids, lactulose, dextrose,

metronidazole, pentoxyfylline and banamine. She developed episodes of ventricular tachycardia. An ultrasoundguided

liver biopsy was taken. On ultrasound, the liver appeared small. Due to the grave prognosis associated with

disease progression and the results of the liver biopsy, the owner elected for humane euthanasia.

Gross Description:

Diffusely the liver had an accentuated, lobular pattern (zonal necrosis and degeneration). The

urinary bladder mucosa was uniformly red (congestion / hemorrhage). The uterus was thickened with a reddish

mucosa and two, small, fluid-filled endometrial cysts measuring 1 and 0.5 cm in diameter respectively (endometrial

lymphatic cysts).

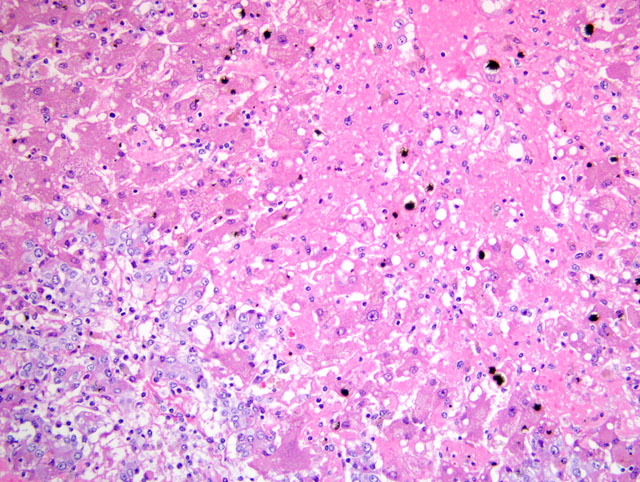

Histopathologic Description:

Diffusely disrupting and collapsing the hepatic lobular architecture and distorting the

hepatic cords, there is marked loss of centrilobular and midzonal hepatocytes. The remaining hepatocytes have loss

of cellular detail, swollen cytoplasm with multivacuolation (degeneration) or pyknotic nuclei (necrosis). Many

hepatocytes contain globular to granular, irregularly-shaped, yellow-brown material (hemosiderin / bile). The

hepatic sinusoids are markedly expanded by eosinophilic, homogeneous material (edema) and erythrocytes

(congestion). The parenchyma is diffusely but mildly infiltrated with macrophages, neutrophils, and rare plasma

cells and lymphocytes. Many Kupffer cells are distended with intracytoplasmic, dark-brown pigment (hemosiderin)

and rare erythrocytes (erythrophagocytosis). The portal areas are closely approximated (lobular collapse), often with

portal-portal bridging, and are markedly expanded by proliferation of bile ducts that are lined by cuboidal to

columnar cells with abundant often vacuolated cytoplasm, and a large vesicular nucleus. The cells occasionally pile

up but have rare mitotic figures (biliary hyperplasia). Multifocally, the portal areas are infiltrated by fewer

lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and neutrophils and rare eosinophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Subacute hepatopathy with submassive hepatocytic degeneration

and necrosis with lobular collapse, biliary hyperplasia, hemorrhage and mild, diffuse pericholangial hepatitis.

Condition:

Equine serum hepatitis

Contributor Comment:

Ever since its discovery by Theiler (thus the name Theilers disease) in South Africa,

this remains one of the most common causes of hepatic failure in horses. The onset of clinical signs is acute, and

often, rapidly progresses to death. Occasionally, some horses survive.(4) The disease is also known as serum

hepatitis, serum sickness, and idiopathic acute hepatic failure. Theilers disease is historically associated with

injection of biologicals of equine origin such as tetanus antitoxin, Clostridium perfringens toxoids, equine

herpesviral vaccine, pregnant mare serum and commercial plasma.(1,2,4,5,7) Clinically, the disease is manifested

after an incubation period ranging from 40-90 days following an exposure to a biological. The clinical

manifestations are reflective of underlying hepatic and central nervous system (CNS) disorders. These include

icterus, mild circling to maniacal behavior, continuous walking, head pressing, blindness and ataxia. Although an

association between the disease and use of a biological of equine origin is well accepted, sporadic cases without a

history of biological make some veterinarians think there is an alternate cause, possibly a virus.(6) However, to

date, no virus has been isolated. Macroscopically, the liver is flabby, either small or enlarged and dark-green to

dark-brown. Microscopic changes invariably progress rapidly as in this case.

A liver biopsy taken 24 hours before euthanasia had expanded zones of hepatocytes arranged in ill-defined cords

with a mild, interspersed, inflammatory infiltrate that followed the central veins and the portal units. The overall

structural integrity was maintained. Thirty six hours later, the microarchitecture was obscured with massive drop

out of hepatocytes, parenchymal collapse, poorly discernible central veins and portal triads that are variably

expanded by proliferating biliary ductules, cellular infiltrates, and edema when the animal was euthanized. The

ductular proliferation of cholangiolar or oval cells is a regenerative response to massive hepatocyte loss. The

histologic progression was dramatic. Hepatic cord disruption and hepatocyte loss cause collapse of the lobular

outline bringing the portal units closer. Histologic change in the CNS included Alzheimer type II astrocytes

characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy.

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis, massive, diffuse, severe, with intrahepatic

cholestasis and hemorrhage, and multifocal moderate biliary hyperplasia.

Conference Comment:

Participants briefly reviewed histomorphologic pattern recognition in hepatic lesions,

emphasizing its utility in narrowing the differential diagnosis based on a sound understanding of the susceptibility of

the parenchymal cells in each zone of the lobule to various insults. Specifically, centrilobular (i.e. zone 3,

periacinar) hepatocytes are preferentially affected in many hepatopathies because of two key biologic features: 1)

centrilobular hepatocytes are supplied by blood with the lowest concentration of oxygen in the liver, thereby making

them exquisitely sensitive to hypoxic injury, and 2) they possess the greatest expression of biotransformation

enzymes, including members of the cytochrome P450 superfamily (i.e. mixed-function oxidase system) responsible

for most phase I biotransformation reactions that may yield transient reactive intermediates, rendering centrilobular

hepatocytes highly susceptible to injury by toxins that are activated by cytochromes P450. By contrast, periportal

(i.e. zone 1) hepatocytes, due to their close proximity to vascular inflow, are most susceptible to direct-acting

toxicants. While the cause and pathogenesis of Theilers disease remain enigmatic, the characteristic centrilobular to

massive distribution of hepatocellular necrosis is helpful in making the diagnosis.(7)

Two noteworthy observations regarding this interesting condition were reiterated during the conference. First, while

the majority of cases occur in horses that have received injections of equine-origin biologics, many sporadic cases

have occurred in horses that have not received such injections, leading to persistent suspicion of a serumtransmissible

viral etiology, similar to hepatitis B in humans. Second, although rapid clinical progression typically

culminating in death within 24 hours suggests an acute disease course, the microscopic appearance indicates some

degree of chronicity, and acute hepatocellular necrosis and hemorrhage are not typical. Rather, there is centrilobular

to massive loss of hepatocytes, macrovesicular fatty change with degeneration of most remaining hepatocytes,

extensive deposition of bile pigments in Kupffer cells and hepatocytes, and mild portal fibroplasia with occasional

ductular proliferation.(7)

Endogenous toxins associated with hepatic and, less commonly, renal failure may cause hepatic encephalopathy, as

was diagnosed in the horse of this case. Horses are similar to humans, yet unique among domestic animal species,

in that they characteristically develop Alzheimer type II astrogliosis attributable to hepatic encephalopathy, with

myelin vacuolation being mild to absent. By contrast, in most domestic species the predominant histologic feature

of hepatic encephalopathy is spongy vaculoation of myelin, particularly at the junction of cerebral gray and white

matter and around the deep cerebellar nuclei, with Alzheimer type II astrogliosis being a variable finding.(3)

References:

1. Aleman M, Nieto JE, Carr EA, Carlson GP: Serum hepatitis associated with commercial plasma transfusion in

horses. J Vet Intern Med

19:120-122, 2005

2. Guglick MA, McAllister CG, Ely RW, and Edwards WC: Hepatic disease associated with administration of

tetanus antitoxin in eight horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc.Â

206:1737-1740, 1995

3. Maxie MG, Youssef S: Nervous system.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed.

Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 386-387. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

4. Messer NT, and Johnson PJ: Serum hepatitis in two brood mares. J Am Vet Med Assoc

204:1790-1792, 1994

5. Messer NT, and Johnson PJ: Idiopathic acute hepatic disease in horses: 12 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc

204:1934-1937, 1994

6. Smith HL, Chalmers GA, and Wedel, R: Acute hepatic failure (Theilers disease) in a horse. Can Vet J

32:362-364, 1991

7. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic

Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 298-301, 316-324, 343-344, 364-365. Elsevier Saunders,

Philadelphia, PA, 2007