Signalment:

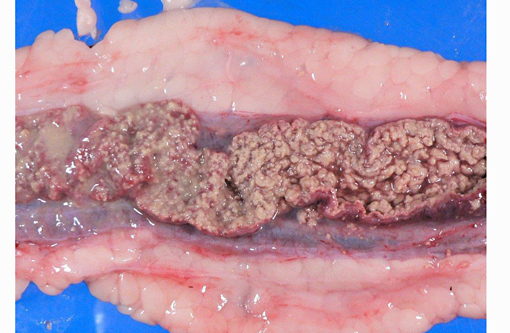

Gross Description:

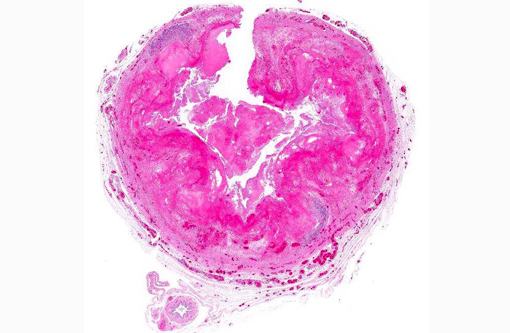

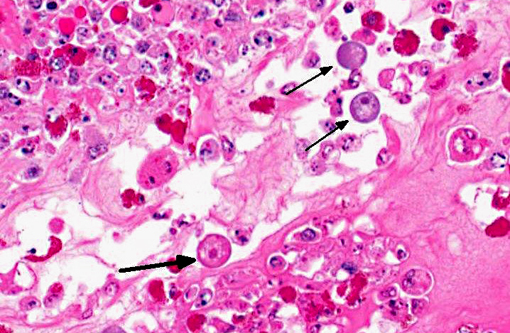

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Herbivorous turtles are thought to serve as the natural host for E. invadens. In turtles, the parasite likely lives as a commensal symbiont without any pathogenicity.(2) While in the trophozoite state, these protozoa locomote and feed by forming pseudopodia. The resistant cyst stage is excreted in the feces. Following contamination of the water supply of snakes and lizards, the protozoa are ingested and induce a fulminating enteritis and hepatitis in these species. The clinical signs include regurgitation of undigested food and severe diarrhea, occasionally accompanied by blood- or bile-tinged green mucus, and/or remnants of intestinal mucosa.Â

The most characteristic microscopic lesion induced by E. invadens is severe intestinal erosion, ulceration and inflammation, often with formation of fibrinonecrotic pseudomembranes (diphtheritic enteritis).(2,6) Typically, the ileum and colon are the most severely affected intestinal segments and the affected gut wall is severely thickened. The protozoa invade blood vessels, spread systemically and induce necrosis and inflammation in various extra-intestinal tissues, especially the liver.Â

This anaconda has typical diphtheritic ileitis with numerous amoebic trophozoites and similar (though less severe) inflammation is observed in the large intestine. Although the protozoa often migrate in the sinusoids of liver and occasionally in the vessels of lung and kidney, there is no apparent damage to these organs in this case. We conferred with a veterinarian in the zoological garden in an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of infection in this case and were unable to reach a definitive conclusion; however, we suspect that the anacondas water supply was contaminated by turtle feces.Â

Immunosuppression has been suggested as an important predisposing factor in snake Entamoeba infections. There is a recent report of diphtheritic colitis caused by an amphibian Entamoeba sp. in a Boa constrictor kept in a zoological garden.(6) Histopathological changes in this case were limited to the large intestine, implying that this Entamoeba may have a lower pathogenicity than E. invadens. As the snake suffered simultaneously from endoparasitism and inclusion body disease, the animal was suspected to be in an immunocompromised state. Our case also demonstrated moderate atrophy of lymphoid follicles in spleen, which may be a result of inadequate nutrition; however, the details are unclear.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Intestine: Enteritis, fibrinonecrotic, circumferential, diffuse, severe, with numerous amoebic trophozoites.Â

2. Mesenteric vessels: Vasculitis, necrotizing, multifocal, moderate.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent summary of Entamoeba invadens in reptiles. Chelonians and crocodilians are considered to be the natural hosts of E. invadens and may serve as a reservoir for infection in snakes and lizards in captivity. As noted by the contributor, transmission is typically feco-oral (probably related to contamination from turtle feces) and the most common presentation of invasive amoebiasis in reptiles is enteritis, often with subsequent hepatitis following hematogenous dissemination via the portal vein. After entering the mesenteric circulation, trophozoites may disseminate to other organs, although this is uncommon. There is a single report of amoebic myositis in a water monitor (Varanus salvator), presumably due to either hematogenous spread or direct invasion via skin wounds.(1)

Entamoeba histolytica is the etiologic agent of amoebic dysentery in humans, with an incidence of up to 500 million clinical cases per year, including up to 100,000 fatalities.(5) E. histolytica is distributed worldwide among humans, but also occurs in a broad range of New and Old World monkeys and apes, and can be transmitted to dogs, cats, cattle and macropods; the pathogenesis is similar to E. invadens.(5,7,8) In Old World monkeys, amoebic dysentery typically induces necrotizing colitis, with occasional dissemination to the liver or (rarely) other tissues. Conversely, in certain species of leaf-eating monkeys, including colobus monkeys, silver leaf monkeys, douc langurs and proboscis monkeys, fibrinonecrotizing gastritis is the principle lesion associated with E. histolytica. It is thought that the normal neutral pH within these gastric compartments provides a favorable environment for excystation of ingested E. histolytica, followed by tissue invasion.(7) E. histolytica can be transmitted to dogs, cats and cattle, where it typically causes colitis;(3) gastric amoebiasis has been reported in a wallaby, a species with a complex, sacculated stomach adapted for fermentation that is similar to that of leaf-eating monkeys.(7)

In addition to severe fibrinonecrotic enteritis, conference participants found the multifocal necrotizing vasculitis and thrombosis within adjacent mesenteric vessels particularly striking. The etiology of this finding is unclear; discussion centered upon the possibility of direct damage from amoebic trophozoites versus the potential of a concomitant gram-negative septicemia (i.e. salmonellosis) with subsequent vasculitis.Â

References:

1. Chia MY, Jeng CR, Hsiao SH, Lee AH, Chen CY, Pang VF. Entamoeba invadens myositis in a common water monitor lizard (Varanus salvator). Vet Pathol. 2009;46(4):673-676.

2. Frye F. Reptile Care: An Atlas of Diseases and Treatments. Vol. I. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications; 1991:278-285.

3. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP. An Atlas of Protozoal Parasites in Animal Tissues. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1998:10-11.

4. Gelberg, HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, and peritoneal cavity. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2012:395.

5. Petri, WA Jr. Intestinal invasion by Entamoeba histolytica. Subcell Biochem. 2008;47:221-232.

6. Richter B, K+�-+bber-Heiss A, Weissenb+�-�ck H. Diphtheroid colitis in a Boa constrictor infected with amphibian Entamoeba sp. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;153:164-167.

7. Stedman NL, Munday JS, Esbeck R, Visvesvara GS. Gastric amebiasis due to Entamoeba histolytica in a Dama Wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Vet Pathol. 2003;40(3):340-342.

8. Strait K, Else JG, Eberhard ML. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. London, UK: Academic Press; 2012:206-208.