Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

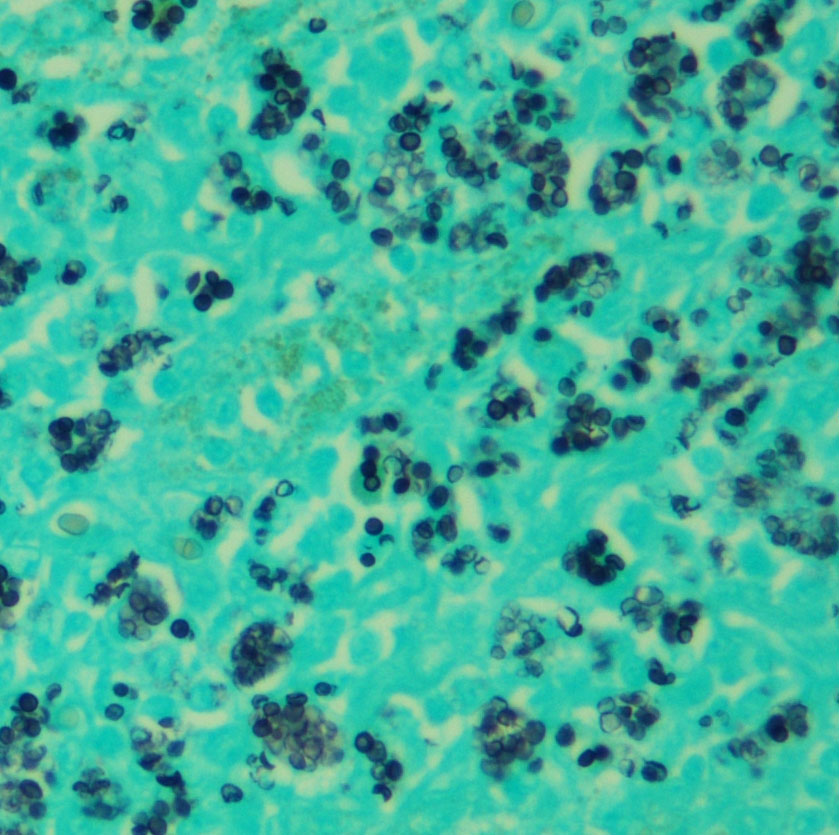

Large numbers of macrophages with intracytoplasmic yeasts are also present in the lungs (alveolar interstitium and lumina), spleen (red pulp), liver (portal tracts and sinusoids), kidney (perivascular interstitium), intestine (lamina propria and Peyers patches), and bone marrow (diffuse), as well as circulating macrophages in the brain and heart vasculature. A GMS stain revealed abundant intracytoplasmic 2-4 µm diameter yeasts.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

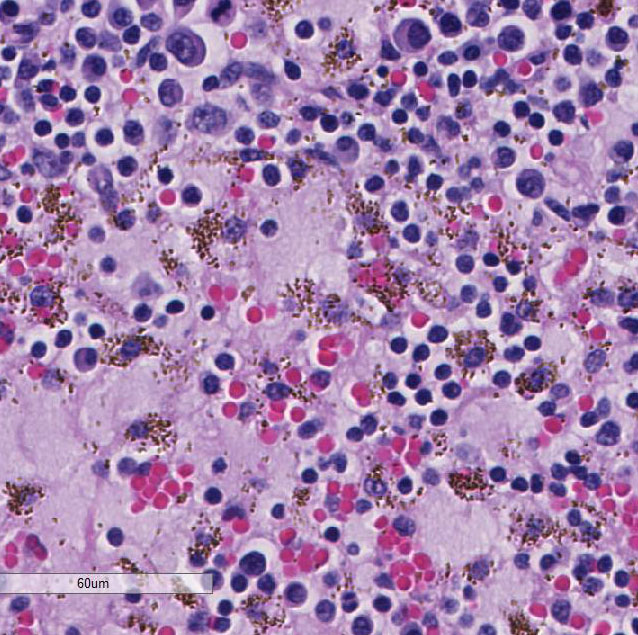

A bone marrow

aspirate showed high nucleated cellularity with rare precursor cells and abundant

macrophages containing numerous round to oval yeast bodies (~2-4 microns in

diameter) that have a thin outer halo with an eccentrically placed, crescent

shaped, basophilic nucleus. The findings were consistent with histoplasmosis.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Infection begins

with ingestion or inhalation of soil contaminated with Histoplasma

microconidia.4 Pulmonary or gut-associated macrophages phagocytose

the microconidia, which germinate into the yeast form and replicate within

phagosomes.7 In immuno-competent animals, Th1 cell-mediated immune

responses eliminate the infection; in immunosuppressed states, the yeast-laden

macrophages disseminate widely via the lymphatics and blood vessels to lymph

nodes, liver, bone marrow, spleen, adrenal glands, etc.7

Histoplasma

capsulatum

evades the hosts extracellular immune defenses by residing intracellularly

within macrophages, and by concealing immunostimulatory beta-glucan cell wall

components with non-immuno-stimulatory alpha-glucans.5,7 The yeast

is internalized via macrophage complement receptors such as CR3 and CR4 while

avoiding activation of pro-inflammatory receptors such as TLR2 and TLR4.5

Once inside the phagosome, the fungus produces antioxidant enzymes including

superoxide dismutase Sod3 and catalases CatB and CatP.5,7 It also

prevents acidification of the phagosome and fusion of lysosomes by as yet

unknown mechanisms.5 Other described virulence factors are involved

with nutrient acquisition and production, including iron-scavenging hydroxamate

siderophores, calcium-binding protein Cbp1, and various nucleic acid- and vitamin-synthesizing

enzymes.5,7

Clinical signs include

fever, malaise, emaciation, diarrhea, nonregenerative anemia, and respiratory

distress.2-4 Gross lesions include enlargement or thickening of

affected organs including lymph-adenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly,

thickened bowel walls, and interstitial pneumonia.2-4

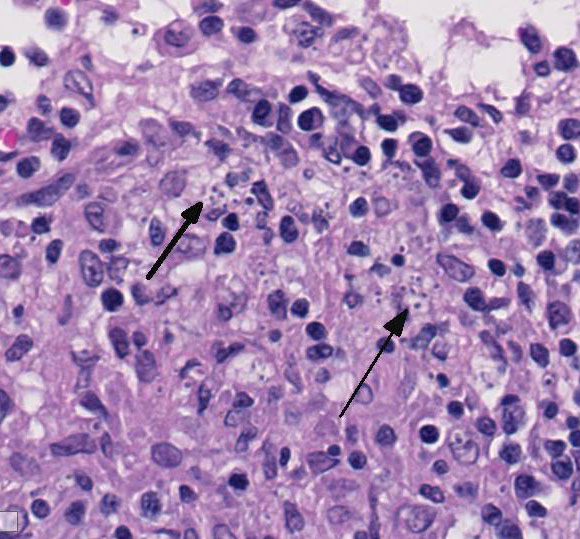

Histologically, organ in-volvement is characterized by granulo-matous

infiltration with large numbers of mononuclear phagocytes bearing character-istic

intracellular yeasts, as well as variable numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells,

and multinucleated giant cells.3,4 Histochemical stains such as

silver stains, periodic acid-Schiff, or Giemsa stains can highlight yeast

organisms. For antemortem diagnosis, cytology from rectal scrapings or fine

needle aspirates from lymph nodes and internal organs can also demonstrate

intrahistiocytic yeasts.3,4,6 Fungal culture is hazardous, however,

due to infectivity of microconidia produced in the mycelial phase.

Ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole alone or in combination with

amphotericin B has been used to successfully treat dogs and cats.2-4

Itraconazole is the recommended treatment of choice.3,4

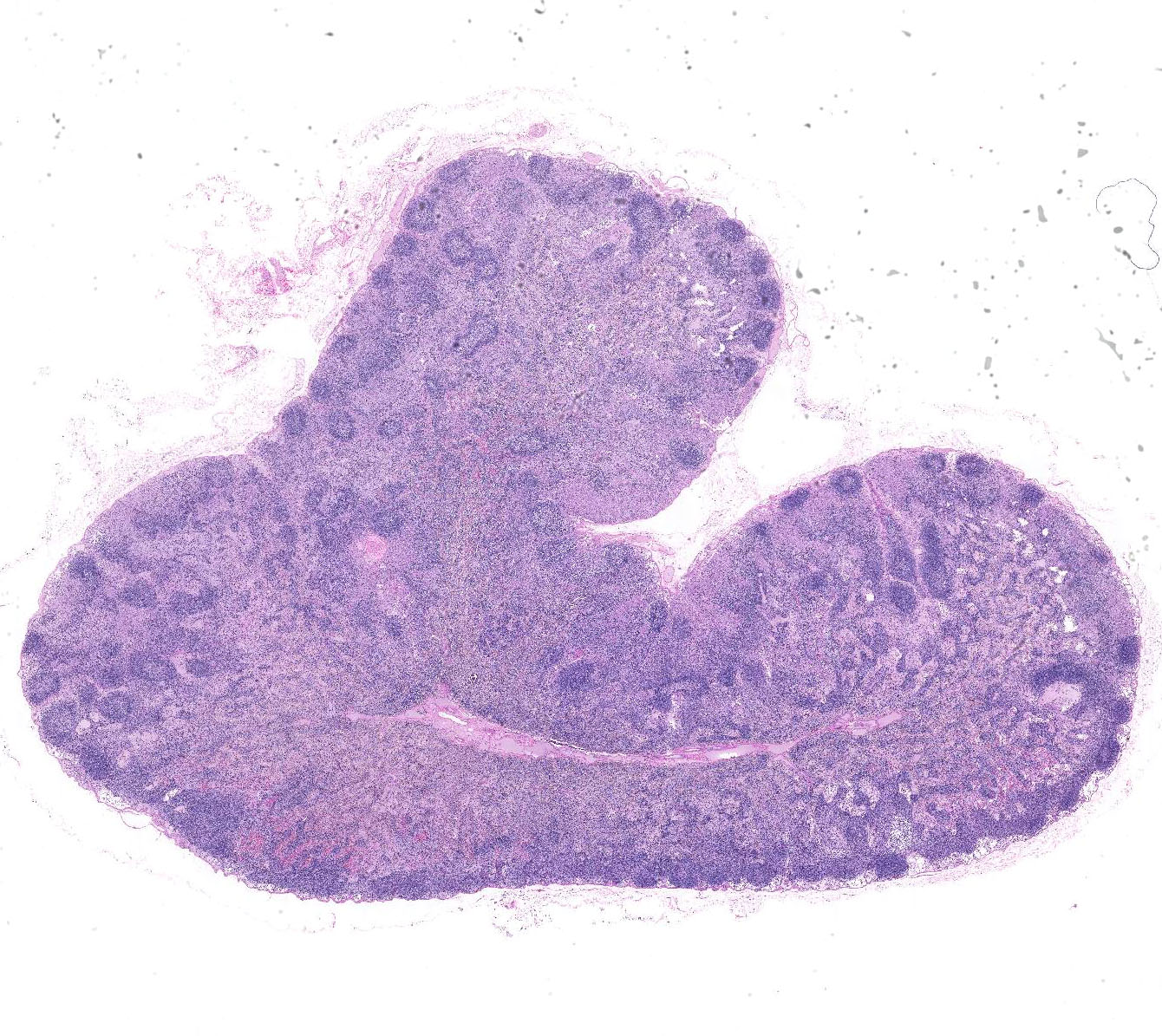

JPC Diagnosis:

2. Lymph node: Draining hemorrhage with hemosiderosis.

Conference Comment:

Conference participants also discussed dendritic cells as an important component of the innate immune response to this or-ganism. Dendritic cells typically phagocytose and destroy the organism with higher efficacy than macrophages. In addition, they present antigens to naïve CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes via MHC-1 to generate a T cell mediated immune response and destroy infected cells.1 Cell-mediated immunity (CMI) is crucial for the host to clear the organism and T cells, as the central effectors CMI, are necessary to degrade the pathogen.1,5,7 Severe disease occurs in immunosuppressed animals as well as hosts with a bias toward a Th2 humoral response. Humoral immune responses generally have a limited role in the clearance of intracellular pathogens.5,7

The nature of the inflammation within the lymph node generated spirited discussion during the conference, as it has so many times before over the many years of the Wednesday Slide Conference. Some con-ference participants preferred histiocytic, rather than granulomatous lymphadenitis. Those favoring the term histiocytic noted the paucity of multinucleated giant cells and lack of activated fibroblasts surrounding aggregates of infected macrophages, histologic features often associated with the more typical granulomatous response. Due to variation in sections, others noted more numerous multinucleated giant cell macro-phages surrounding accumulated epithelioid macrophages and preferred granulomatous lymphadenitis. Conference participants also posited that the subcapsular location of many of the aggregating macrophages may be secondary to antigen presentation within pre-existent lymphoid follicles. This would stimulate follicular lymphoid hyperplasia and medullary plasmacytosis with Russell body-laden Mott cells, as seen in this case.

References: