Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 12, Case 1

Signalment:

5-month-old, female intact, Domestic Shorthair, Felis catus, cat.

History:

The patient presented to the referring veterinarian at 3 months of age for a 1 month history of abdominal distention which worsened post-prandially. Approximately 45 mL of yellow fluid was removed from the abdomen at this time. The patient was then referred to Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital for further work up: serum biochemistry demonstrated elevated liver enzymes and hyperbilirubinemia. Abdominal ultrasound showed severe intrahepatic biliary tract dilatation with no identifiable gallbladder, and 300 mL of a similar abdominal fluid was removed. Top differentials included a ductal plate malformation or other congenital malformations. The patient continued to decline despite medical management (Ursodiol and Spironolactone) and was humanely euthanized 1 month later.

Gross Pathology:

On postmortem examination, there was moderate icterus and musculature atrophy. There was approximately 1300 mL of serous, yellow-green fluid in the abdominal cavity. The liver was yellow-to-green tinged and markedly enlarged with distorted, rounded lobes. There was serosal thickening with adhesions from the liver to the diaphragm and stomach and there was no identifiable gall bladder. On cut section, the yellow to green discoloration was present throughout the parenchyma and there were numerous, tortuous, markedly dilated bile ducts filled with dark green fluid. The left lobe of the pancreas was edematous, nodular and irregular and markedly decreased in size with adhesions to the stomach. The spleen was very small, rounded and adhered to the stomach. The mesentery of the greater curvature of the stomach had prominent, slightly tortuous vasculature and was expanded by green-tinged edema.

Laboratory Results:

Chemistry:

|

Phosphorus |

7.0 mg/dL |

(3.0 - 6.0) |

|

Total Protein |

6.2 g/dL |

(6.3 - 8.0) |

|

CK |

828 IU/L |

(60 – 350) |

|

T-Bilirubin |

1.6 mg/dL |

(0.0 - 0.1) |

|

ALP |

392 IU/L |

(10 – 80) |

|

ALT |

893 IU/L |

(30 – 140) |

|

AST |

275 IU/L |

(15 – 45) |

|

GGT |

22 IU/L |

(0 - 0.5) |

|

Sodium |

154 mEQ/L |

(149 – 157) |

|

Potassium |

6.12 mEQ/L |

(3.7 - 5.4) |

|

Chloride |

116.6 mEQ/L |

(115 – 125) |

|

Bicarb |

16.3 mEQ/L |

(13 – 22) |

|

Anion Gap |

27 mmol/L |

(16 – 26) |

|

Calc Osmolality |

317 mOsm/Kg |

|

|

Lipemia |

20 |

(0 – 50) |

|

Hemolysis |

99 |

(0 – 50) |

|

Icterus |

2 |

(0 – 1) |

Urinalysis:

|

U-Protein/Create |

0.54 Ratio |

(0.0-0.19) |

|

Urine Protein |

2+ |

|

|

Urine Bilirubin |

1+ |

|

|

Urine pH |

6 |

|

Abdominal Fluid Analysis & Cytology:

|

Fluid Color |

Yellow |

|

Fluid Clarity |

Cloudy |

|

NCC Fld |

700#/uL |

|

RBC Fld |

<10000 #/uL |

|

Fluid PCV |

0 |

|

Refr Protein Est |

3.0 g/dL |

|

Neutrophils # |

399 #/uL |

|

Neutrophils % |

57% |

|

Large Mononuclear # |

287 #/uL |

|

Large Mononuclear % |

41% |

|

Lymphocytes # |

14 #/uL |

|

Lymphocytes % |

2% |

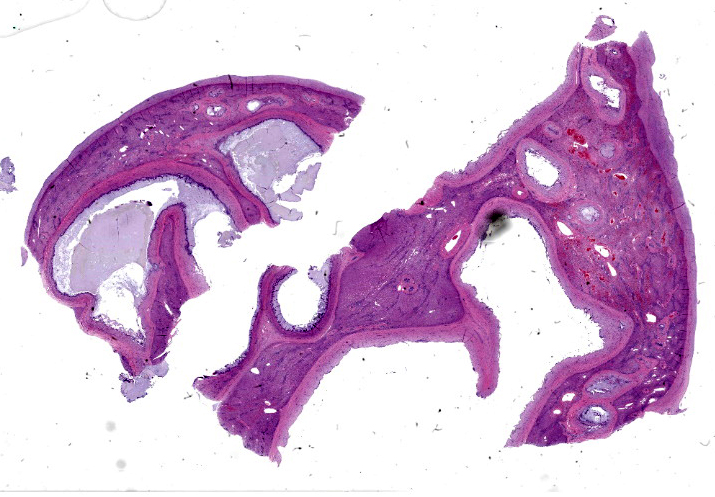

Microscopic Description:

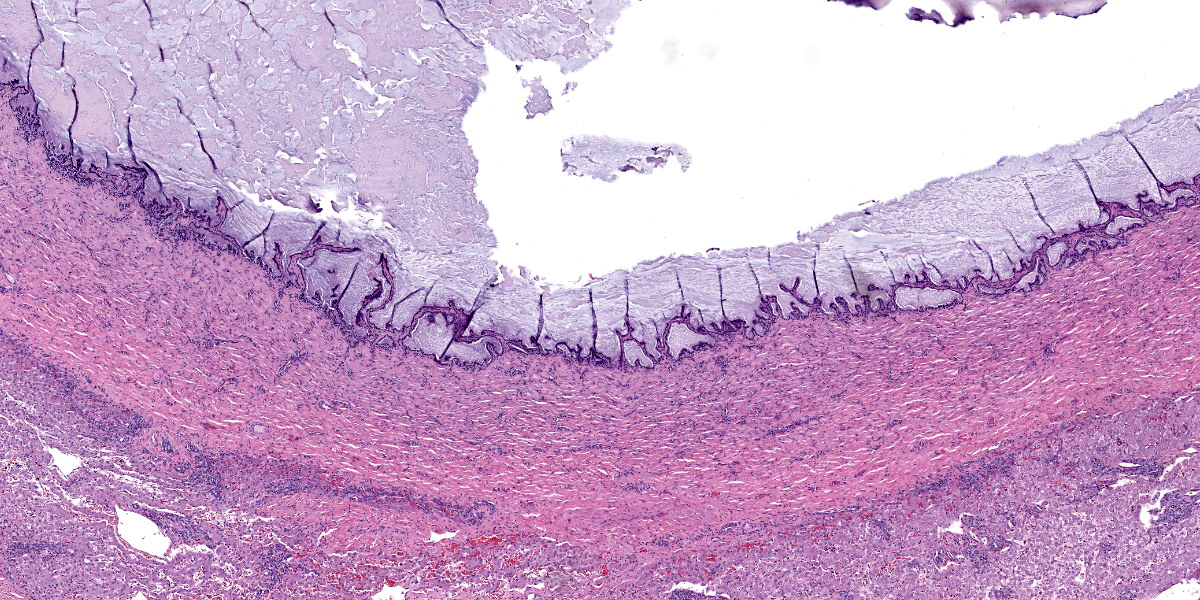

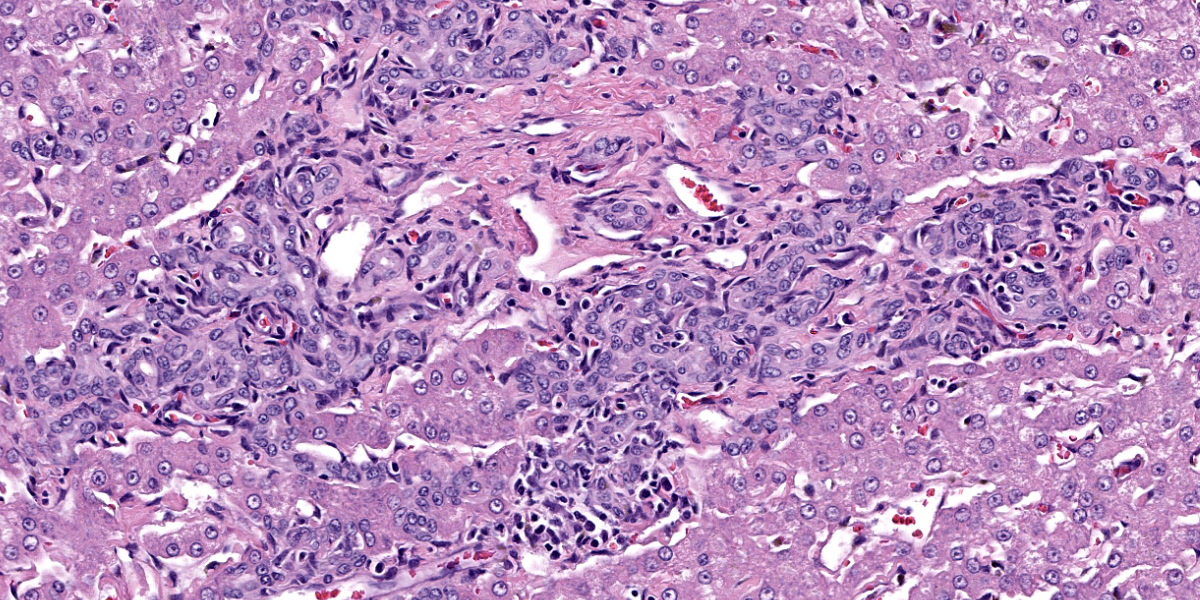

The liver capsule is thickened by variably mature fibrous to myxomatous connective tissue up to 0.6 mm thick with few regularly spaced vessels. Within the adjacent hepatic parenchyma, there are markedly dilated biliary profiles with thickened fibrous capsules. Cystic biliary spaces are lined by elongated and branching villi of biliary epithelium. Within the lumen there is a homogenous basophilic to amphophilic occasionally wispy to vacuolated material. Portal regions are diffusely surrounded by fibrous stroma which bridges between portal regions and entraps islands of hepatocytes. Associated with portal tracts and fibrosis, there are abundant torturous biliary profiles with oval cell hyperplasia and arteriolar reduplication. Portal veins are often small and there is variable lymphatic dilation. Mild infiltrates of neutrophils with fewer lymphocytes, plasma cells and Kupffer cells dissect portal regions. There is increased connective tissue surrounding central veins and multifocal mild sinusoidal dilation.

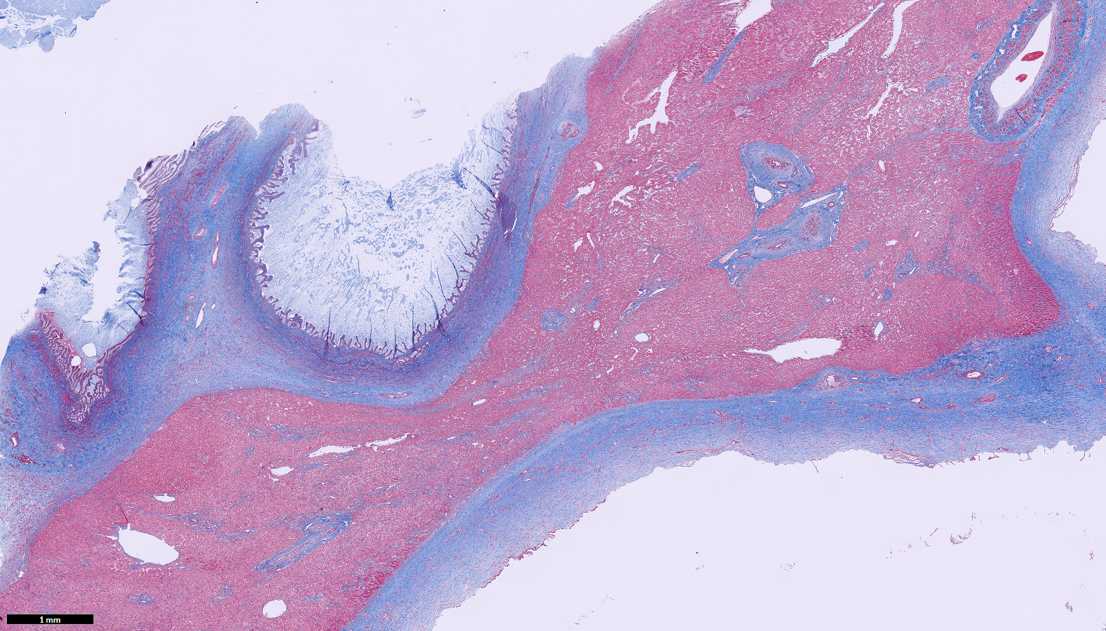

Masson’s Trichrome Histochemistry:

Liver: Trichrome staining demonstrates marked fibrosis surrounding dilated biliary profiles, often entrapping islands of hepatocytes. There is a finer collagen network bridging remaining portal regions and surrounding central veins.

Cytokeratin 19 Immunohistochemistry:

Liver: There is moderate to strong immunoreactivity to cytokeratin 19 throughout cystic bile ducts and proliferative biliary epithelium within portal regions and extending between lobules. Occasionally, individual oval to spindloid cytokeratin 19-positive cells directly oppose periportal hepatocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Chronic marked bridging fibrosis with ductular reaction, arteriolar reduplication, portal vein hypoplasia and marked cystic dilation of bile ducts (Caroli’s disease); moderate central vein fibrosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Physical exam, ultrasound, gross and histologic findings in this case are most suggestive of Caroli malformation/disease, which is a ductal plate malformation (DPM) characterized by congenital hepatic fibrosis and cystic bile ducts.1

DPMs are a group of developmental biliary disorders rarely reported in veterinary species.1 In normal development, hepatoblasts are bipotent, capable of differentiating into biliary epithelium or periportal hepatocytes. The fate of hepatoblasts is largely dependent on transcription factors. Hepatoblasts that give rise to biliary epithelium undergo tubulogenesis, forming a double layer of cuboidal cells surrounding a rudimentary portal vein. This coordinated series of events is orchestrated by TGF-β, Notch, and Wnt signaling pathways, forming the embryonic ductal plate.7 Hepatoblasts that do not undergo tubulogenesis either involute or differentiate into periportal hepatocytes.1,5-7

Malformations within the ductal plate arise when hepatoblasts do not undergo tubulogenesis and also fail to involute, resulting in persistent embryonic bile ducts. It is important to note that DPM encompasses a continuum of phenotypes which reflect the level at which the developing biliary tree is affected.1 This spectrum includes Caroli malformation (presented in this case), biliary hamartomas (also referred to as von Meyenburg complexes), congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF), and polycystic liver disease (PCLD).1,5 In cases of Caroli malformation, disruption occurs at the level of segmental bile ducts (first branch of the hepatic duct), leading to large dilated/cystic persistent ducts.

Few cases of DPMs have been reported in cats, including Caroli malformation with a portosystemic shunt,6 congenital hepatic fibrosis8 (see WSC 2019-2020, Conference 7, Case 1), bile duct hamartomas (see WSC 2021-2022, Conference 1, Case 4), and polycystic liver disease (often in combination with adult polycystic kidney disease).3,4 One retrospective study characterized clinical findings in 30 boxer dogs diagnosed with DPMs.5 In this study, the most common clinical feature was increased liver enzymes (n=28/30), followed by gastrointestinal signs (n=16/30), poor body condition (n=14/30), abdominal effusion (n=9/30), and hepatic encephalopathies (n=2/30); however, these changes are not unique to DPMs which can challenge clinical diagnoses. Such data is currently lacking in cats.

Gallbladder atresia has also been reported in dogs with DPMs.5 In the presented case, the gall bladder was not identified with gross or histologic examination.

In cases of congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF), histopathologic findings include bridging hepatic fibrosis, numerous irregular bile duct profiles, diminished or absent portal veins, and arteriolar reduplication. These histologic findings in addition to large, tortuous and cystic biliary ducts are termed Caroli malformation. DPMs lack nodular regeneration, cirrhosis, and cholangitis. Cytokeratin 19 (CK19) is expressed in hepatoblast precursor cells and committed biliary epithelium and can be used as a marker to confirm cellular histogenesis in these cases.1,5

Differential diagnoses include primary portal vein hypoplasia (PVHP), obstructive biliary disease, and lobular dissecting hepatic fibrosis (dogs only).

Primary portal vein hypoplasia (PVHP): In DPMs, intrahepatic presinusoid hypertension may redirect portal flow away from the liver, resulting in an acquired portosystemic shunt. Therefore, decreased/absent portal veins with arteriolar reduplication can overlap between DPMs and PVHPs; however, cases of a PVHP often lack marked biliary hyperplasia, biliary ectasia, and periportal fibrosis.1,2

Obstructive biliary disease: Similar to DPMs, obstructive biliary disease includes bile duct dilation and tortuosity; however, peribiliary fibrosis does not bridge portal regions, and the presence of periductal edema with inflammation are unique to obstructive biliary disease.5

Lobular dissecting hepatic fibrosis: Lobular dissecting hepatic fibrosis is often accompanied by nodular regeneration and cirrhosis, both of which are not features of DPMs.1,2

Contributing Institution:

Colorado State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

https://vetmedbiosci.colostate.edu/vdl/

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Ductal plate malformation.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was the renowned Dr. John Cullen who led participants through a liver-centric conference with 4 cases that emphasized careful review of the slide and taking a ‘census’ of liver features along the way.

The contributor provides an excellent summary of ductal plate malformations in this first case. Dr. Cullen ultimately agreed that the features presented were likely consistent with Caroli’s disease, though there were several important additional criteria to consider. Foremost, there was no evidence of obstruction and/or inflammation as an inciting cause for dilatation of the bile ducts which is an important rule out – this can be complicated as ascending infection often accompanies distension of the duct. That this cat was young (5 months) likely limited inflammation. In addition, as Caroli’s disease affects the large ducts specifically. . Figure 1-3 is supportive on its own for Caroli’s disease. Careful dissection of the entire liver with a good gross description is therefore advisable. Though a lack of a gallbladder is associated with DPMs resembling Caroli’s disease in dogs, gallbladder agenesis has been rarely reported in this condition in cats.

Though the abnormal proliferation of biliary ductules in the fibrotic portal areas was an obvious feature of this case, the absence of portal vein profiles was a bit more subtle. Dr. Cullen emphasized reviewing multiple portal tracts as part of his census and specifically locating the portal vein, hepatic artery, bile duct, and lymphatics and comparing both larger tracts and smaller tracts for features. The latter is important for considering the branch level of primary portal vein hypoplasia as only secondary branches may be hypoplastic. Additionally, the marked dilatation of bile ducts was a helpful feature for this case, though the diagnosis of DPM writ large does not require this if there is modest dilation concurrent with portal vein hypoplasia.

Finally, there are several ancillary features of this slide worth capturing. The thick hepatic capsule likely represents stretching of the liver and increased mechanical response. The marked dilatation of bile ducts increases interstitial pressure which in turn allowed for leakage of fibrinogen in lymph and eventual conversion to the mature collagen seen in section. The degree of fibrosis present with Masson’s trichrome is notable (figure 1-6) as well, and indicates (in a very non-specific vernacular), impaired “cross-talk” between epithelial and mesenchymal tissues during intrahepatic biliary tree development. Material within the ductular lumen stained with Alcian blue (i.e. containing mucus), though ductular epithelial secretions are variable and include other constituents as well.

References:

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:264-267.

- Cullen JM. Summary of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association standardization committee guide to classification of liver disease in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009 May;39(3):395-418.

- Hirose N, Uchida K, Kanemoto H, et al. A retrospective histopathological survey on canine and feline liver diseases at the University of Tokyo between 2006 and 2012. J Vet Med Sci. 2014; 76: 1015–1020.

- King EM, Pappano M, Lorbach SK, Green EM, Parker VJ, Schreeg ME. Severe polycystic liver disease in a cat. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Open Reports. 2023;9(2).

- Pillai S, Center SA, McDonough SP, et al. Ductal Plate Malformation in the Liver of Boxer Dogs: Clinical and Histological Features. Vet Pathol. 2016 May;53(3):602-13.

- Roberts ML, Rine S, Lam A. Caroli's-type ductal plate malformation and a portosystemic shunt in a 4-month-old kitten. JFMS Open Rep. 2018 Nov 20;4(2):2055116918812329.

- Wills ES, Roepman R, Drenth JP. Polycystic liver disease: ductal plate malformation and the primary cilium. Trends Mol Med. 2014; 20:261–270.

- Zandyliet MM, Szatmári V, van den Ingh T, Rothuizen J. Acquired portosystemic shunting in 2 cats secondary to congenital hepatic fibrosis. J Vet Intern Med. 2005 Sep-Oct;19(5):765-7.