Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 20

April 6th, 2018

CASE III: 10621-16 (JPC 4101304).

Signalment: 15-year-old male neutered Domestic shorthair (Felis catus), feline.

History: Necropsy organ samples were submitted to the Diagnostic Laboratory from a euthanized cat with a history of emaciation, jaundice, and difficulty breathing.

Gross Pathology: None provided.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): None provided.

Microscopic Description:

In the lung, many of the alveoli are filled with solid sheets of small cells containing scant amounts of cytoplasm with round to oval nuclei. In some areas, there is marked anisokaryosis. Approximately six mitotic figures can be seen in ten high powered fields. Along with these neoplastic cells, there are numerous and scattered aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Numerous airways are partially filled with plugs of desquamated cells mixed with mucus and inflammatory cells. Marked alveolar emphysema is also observed in these sections.

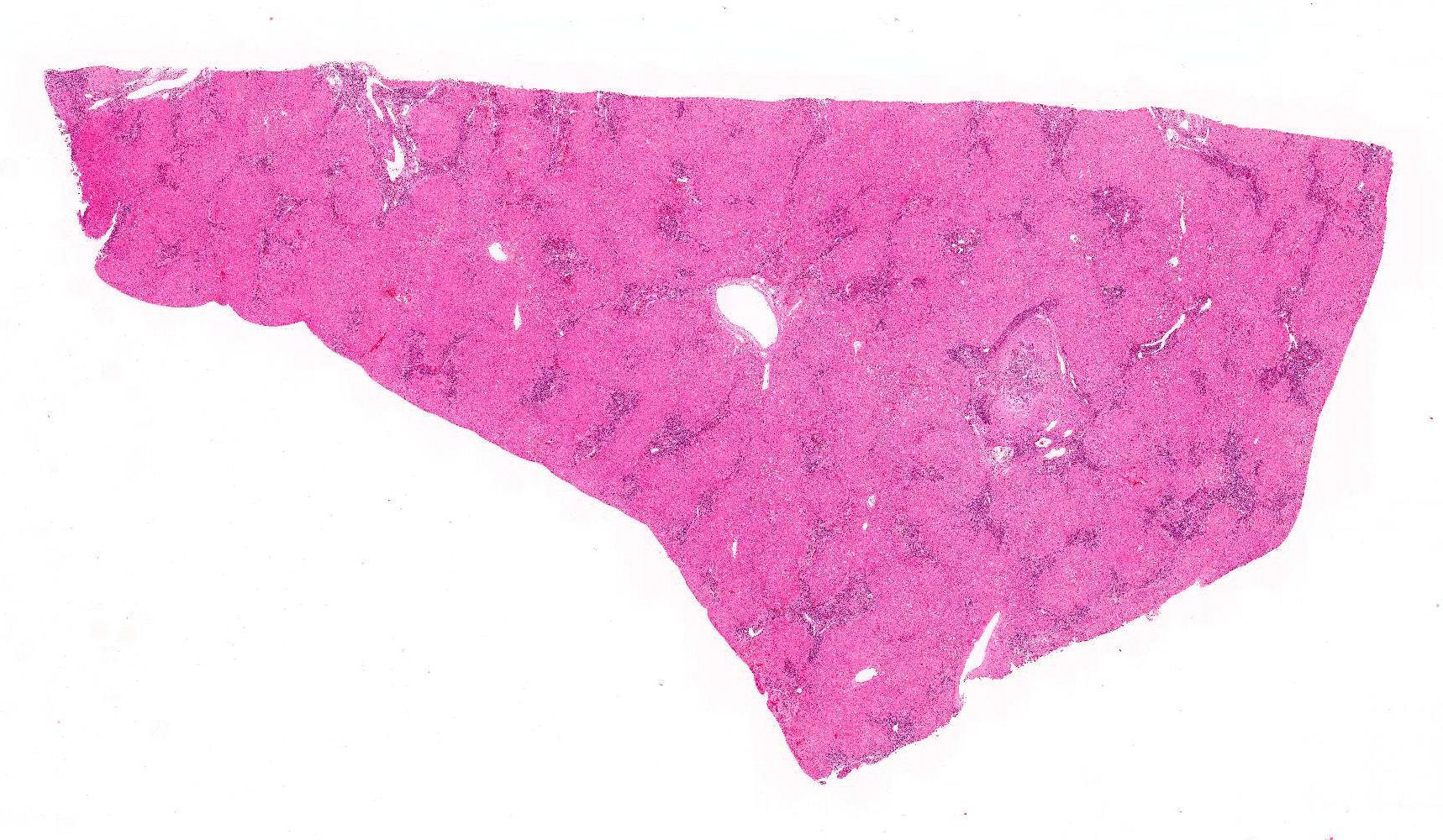

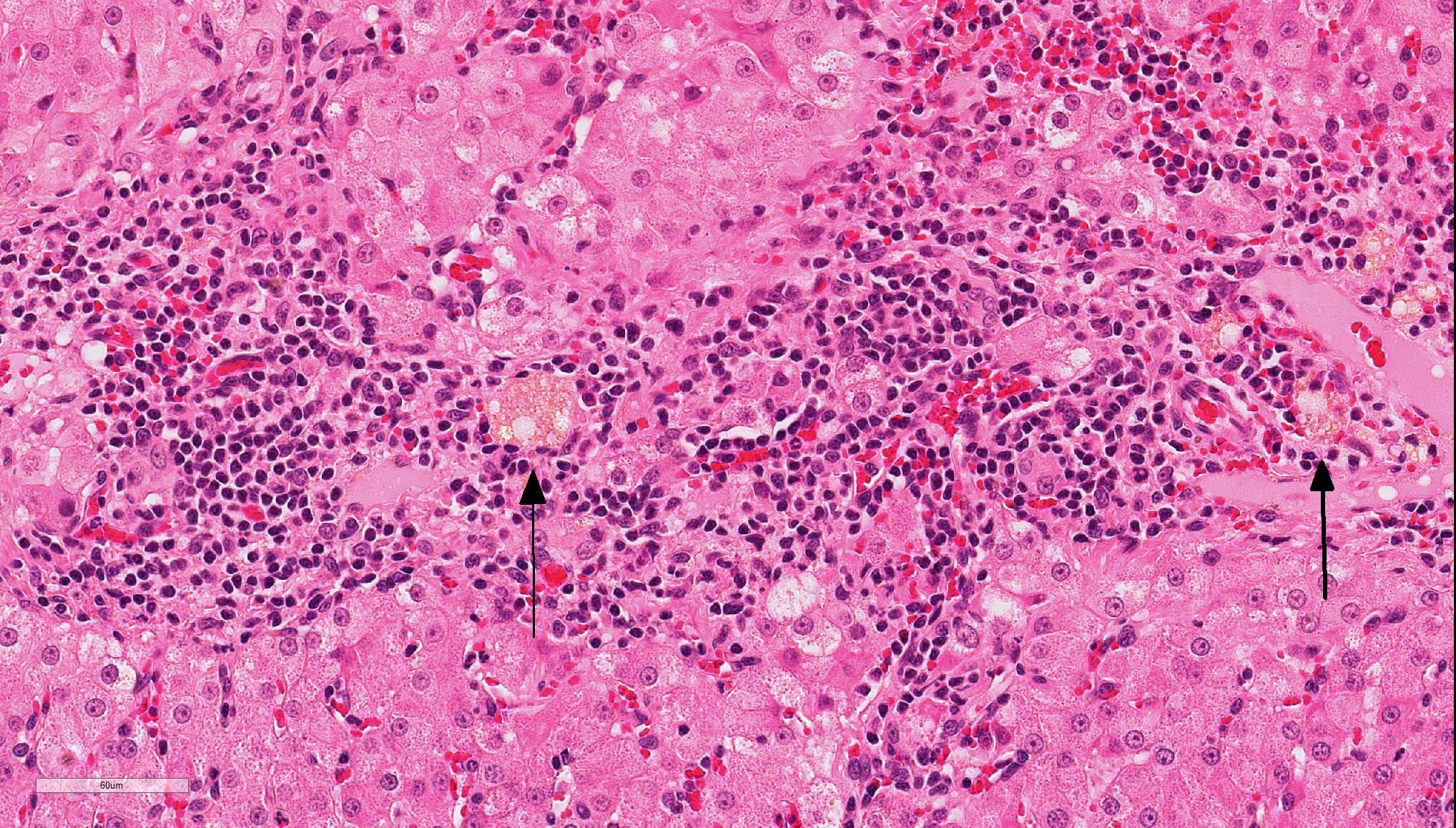

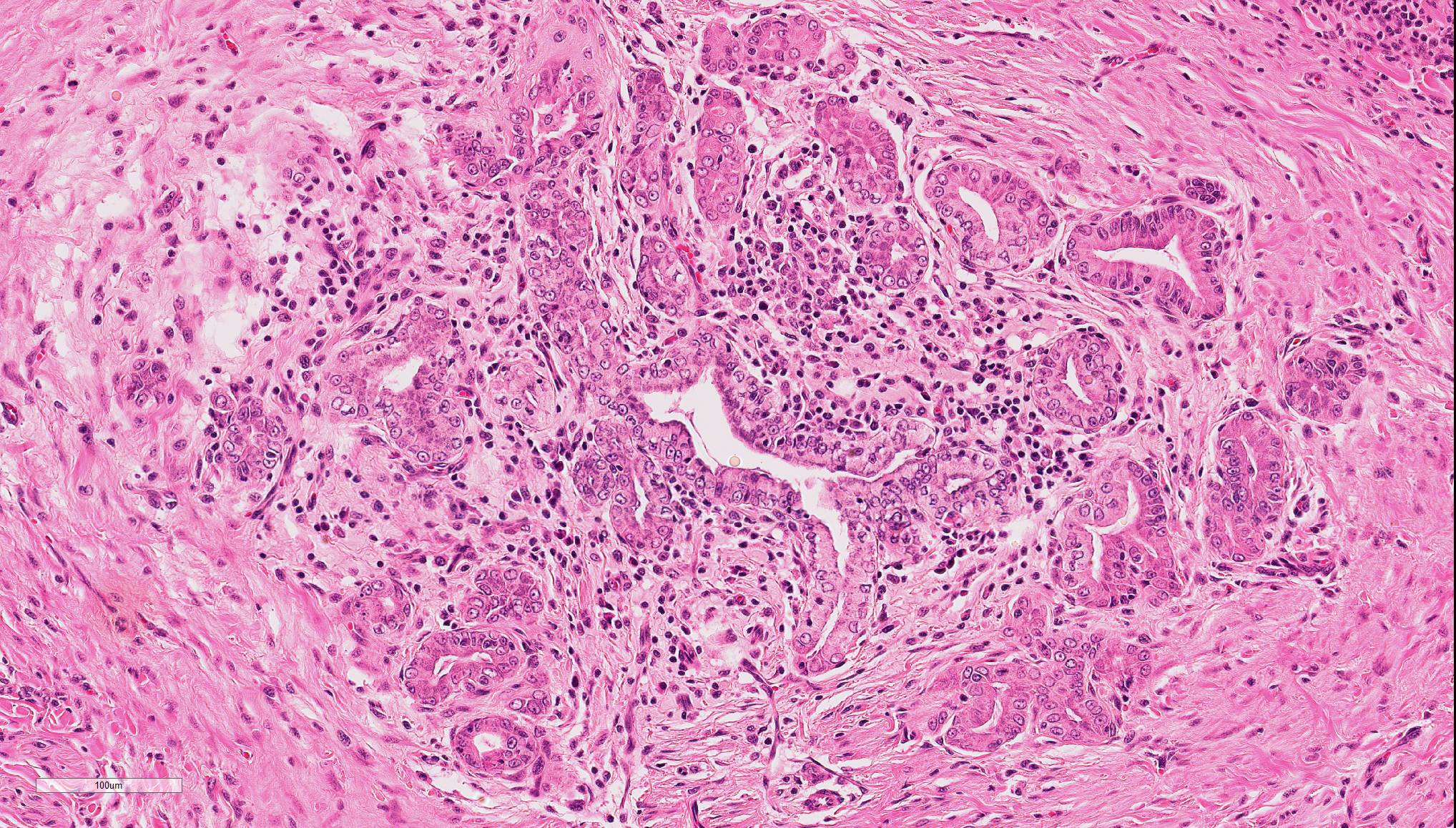

In the liver, periportal areas are markedly expanded due to the presence of large numbers of a mixed population of leukocytes. Limiting plates of lobules are disrupted by this inflammatory infiltrate. Lymphocytes and plasma cells extend into adjacent sinusoids from the periportal areas. Additionally, there is disseminated cholangiolar hyperplasia. Surrounding numerous cholangioles, there is a marked scirrhous response. Some of the larger cholangioles are markedly undulating due to the hyperplastic change and contain a few neutrophils and desquamated epithelial cells in their lumens. A few small aggregates of macrophages containing small cytoplasmic lipid vacuoles are present near the areas of portal inflammation.

In the pancreas, multiple foci of nodular hyperplasia can be seen. These nodules are separated from normal pancreatic parenchyma by slender fibrous septae. Modest disorganization of exocrine pancreas is observed in these hyperplastic areas. There is moderate duct epithelial hyperplasia with small cystic formation in a major pancreatic duct. Occasional small lymphoplasmacytic aggregates can be seen in the interstitium of the pancreas and are sometimes associated with pancreatic islets.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Anaplastic small cell carcinoma – lung

- Severe, chronic, lymphoplasmacytic, cholangitis

- Marked multifocal nodular hyperplasia – pancreas

- Mild multifocal lymphoplasmacytic pancreatitis

Contributor’s Comment: While cholangitis is a relatively common set of liver diseases in cats4,5 the overall prevalence is not well established as definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy and many cases are clinically unapparent during the early stages. In our case, the liver disease was identified coincidentally at necropsy as the cat was euthanized due to its lung cancer. This is a common finding as cholangitis does not typically result in mortality, but rather animals succumb to a concurrent disease process.2

Lymphocytic cholangitis in cats is a slowly progressive inflammatory lesion primarily of older animals that does not have a sex predisposition.9 There have been a number of different pseudonyms used to describe the condition, although there is a proposal to standardize the classification scheme by the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Liver Standardization group. Using their classification, the types of cholangitis can be subdivided into the following four groups: neutrophilic cholangitis, lymphocytic cholangitis, destructive cholangitis, and chronic cholangitis associated with liver fluke infestation.8

The most common type of cholangitis in cats is neutrophilic or suppurative cholangitis and the pathogenesis is through ascending bacterial biliary infections from the gastrointestinal tract.5,8 These cases have portal neutrophilic infiltrates being the primary component during the acute infections and mixed infiltrates including lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates during the chronic stages. Secondary changes include biliary fibrosis and biliary hyperplasia, as well as a low risk of hepatic abscesses.8

Lymphocytic cholangitis is the second most common type of cholangitis, 8 although other studies have ranked it more prevalent than the neutrophilic variant.4 An etiology has not been established for this condition, although it has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis, suggesting that it may have an immune-mediated component. Clinically ,lymphocytic cholangitis tends to be slowly progressive without overt clinical signs during the initial development. Liver enzymes, although they may be elevated, are not directly correlated to the degree of inflammation.2 Lesion severity is not uniform across all liver lobes. 2 Some cases can also histologically mimic hepatic lymphoma8,9 although there are notable key differences which delineate these entities. These differences include bile duct targeting, ductopenia, peribiliary fibrosis, portal B-cell aggregates, and portal lipogranulomas, which are features that are associated with inflammatory rather than neoplastic infiltrates.9

Destructive cholangitis is typically reported in dogs rather than cats and is associated with drug reactions, biliary toxins, and some viral infections. Unlike neutrophils and lymphocytic cholangitis, this variant can cause severe cholestasis up to the point of bile obstruction.

Liver fluke infestation can cause chronic cholangitis is cats. These cases tend to have dilated bile ducts with fibrosis and papillary hyperplasia and pleocellular inflammation and can predispose to the eventual development of biliary carcinomas.8

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Liver: Cholangitis, lymphocytic, chronic, diffuse, severe, Domestic shorthair (Felis catus), feline.

- Liver, bile duct: Cholangitis, neutrophilic, proliferative, focally extensive.

Conference Comment: Feline cholangitis is relatively common and presents in three different varieties: neutrophilic, lymphocytic, and chronic (due to liver flukes). A fourth variety, destructive cholangitis, is most common in dogs and briefly discussed by the contributor above. Microscopically, aside from the inflammatory cell population, they all have similar effects on the hepatic parenchyma: inflammatory infiltrates within portal regions and subsequent periportal to bridging fibrosis and bile duct or oval cell proliferation.

Clinically, these three have distinct presentations. Neutrophilic cholangitis is caused by bacterial cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. These cats typically present with an acute history of lethargy, inappetence, pyrexia, and jaundice. Liver fluke infestations in cats is variable depending on the animal’s environment, but they infrequently cause clinical disease and are usually incidental findings at necropsy.1 The literature frequently associates chronic fluke infections with pancreatitis, however, a recent study conducted on cats on St. Kitts debunked that theory. They found that cats infected with Platynosomum sp. Rarely induces pancreatic damage in cats, and that any chronic pancreatitis present was subtle and most likely not related to the pathogenesis of platynosomosis.6

Lymphocytic cholangitis in cats is a relatively new condition characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates within portal regions and a biliary response with hyperplasia and duct destruction. The pathogenesis is unclear, but an immune-mediated disease has been proposed. One study identified T-cells as the predominant cell type with fewer B-cells admixed (at times forming secondary follicles). This study did not recognize eubacteria (using FISH) which rules out chronic bacterial cholangitis as the cause. Additionally, in cats, where T-cell hepatic lymphoma is common, this study found five microscopic features that distinguish lymphocytic cholangitis from lymphoma: (1) bile duct targeting, (2) peribiliary fibrosis, (3) portal B-cell aggregates, and (4) portal lipogranulomas.9 Additional diagnostics include T-cell receptor (TCR) clonality assays.3 However, this test may not be as reliable as previously supposed, Warren et al.9 found unanticipated results in which a portion of cases with lymphocytic cholangitis were clonal to oligoclonal as were their lymphoma cases. However, most (83%) lymphocytic cholangitis cases were polyclonal as expected.

Recent studies have sought to distinguish lymphocytic from neutrophilic cholangitis in cats with the least invasive modality. Unfortunately, ultrasonographic findings are identical for both conditions: diffuse liver and gallbladder hyperechogenicity and enlarged pancreas.7

During the conference, the moderator identified circumferential fibrosis around bile ducts which are disproportionately small and lined by irregular biliary epithelium. In addition, some sections (not all) contained a single aggregate of irregularly shaped bile ducts with degenerating epithelial cells and neutrophils (resulting in the second conference morphologic diagnosis above). As one of the potential causes of lymphocytic cholangitis is chronic neutrophilic cholangitis, the moderator speculated that this focus of atypical neutrophilic cholangitis might have been contributory to the overall condition. He further articulated that this focus does not appear neoplastic, and although there is a scirrhous response, the cells have normal organization and damaged biliary epithelium frequently produces that type of tissue response. Regarding the possibility of fluke infection in this case, the moderator stated that fluke lesions are large, often macroscopic, and result in marked ductal fibrosis. Finally, he noted that it is important to rule out chronic neutrophilic cholangitis, a condition treatable with antibiotics, by culturing bile solids in these cases.

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Diagnostic Center

School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

http://vbms.unl.edu/nvdls

References:

- Boland L, Beatty J. Feline cholangitis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2017;47(3):703-724.

- Callahan JE, Haddad JL, Brown DC, Morgan MJ, et al. Feline cholangitis: a necropsy study of 44 cats (1986-2008). J Feline Med Surg. 2011; 13:570-576.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:308.

- Gagne JM, Weiss DJ, Armstrong PJ. Histopathologic evaluation of feline inflammatory liver disease. Vet Pathol. 1996; 33:521-526.

- Hirose N, Uchida K, Kanemoto H, Ohno K, Chambers JK, Nakayama H. A retrospective histopathological survey on canine and feline liver diseases at the University of Tokyo between 2006 and 2012. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014; 76(7):1015-1020.

- Koster LS, Shell L, Ketzis J, Rajeev S, Illanes O. Diagnosis of pancreatic disease in feline platynosomosis. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19(12):1192-1198.

- Marolf AJ, Leach L, Gibbons DS, Bachand A, Twedt D. Ultrasonographic findings of feline cholangitis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012; 48(1):36-42.

- M van den Ingh TSGA, Cullen JM, Twedt DC, Van Winkle T, Desmet JV, Rothuizen J. Morphological classification of biliary disorders of canine and feline liver. In: Rothuizen J, Bunch SE, Charles JA, et al. eds. WSAVA Standards for Clinical and Histological Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Diseases. Edinburgh, UK: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:61-76.

- Warren A, Center S, McDonough S, Chiotti R, et al. Histopathologic features, immunophenotyping, clonality, and eubacterial fluorescence in situ hybridization in cats with lymphocytic cholangitis/cholangiohepatitis. Vet Pathol. 2011; 48(3):627-641.