Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 12, Case 3

Signalment:

Adult pregnant Texel sheep (Ovis aries).

History:

12 of ~1,500 sheep exhibited acute depression, red urine (hemoglobinuria), yellow discoloration of the conjunctiva (jaundice), and died over a 10-month period. The sheep grazed on red clover and annual ryegrass, had access to foxtail millet and oat hay, and were supplemented with soybean meal, molasses, and slow-release urea. The flock was administered a multivalent vaccine to prevent clostridial diseases, as well as anthelmintic drugs.

Gross Pathology:

The subcutaneous tissue and the abdominal and pericardial fat were slightly icteric, and the carcass had a brownish hue (presumably due to methemoglobinemia). Bilaterally, the renal parenchyma involving both the cortex and medulla showed a diffuse dark red to black discoloration (hemoglobinuric nephrosis). The urinary bladder contained ~3 mL of dark red urine (hemoglobinuria). The liver was diffusely tan. Additional changes included mild ecchymoses in the serosa of the small and large intestine, abundant pink stable froth in the lumen of the trachea, extra and intrapulmonary bronchi with diffuse pulmonary edema, and free dark, red-tinged fluid in the abdominal and thoracic cavities and pericardial sac (mild hydroperitoneum, hydrothorax and hydropericardium). Incidentally, there were multiple, white, spherical to ovoid, 7-9 mm in diameter, solid nodules in the esophageal muscular layer morphologically resembling Sarcocystis gigantea cysts, and a few adult nematodes compatible with Trichuris sp. in the lumen of the colon.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory tests were performed before autopsy. Aerobic and microaerobic bacterial cultures from lung, liver, kidney, urine, and colon were unremarkable. PCR, qPCR and direct fluorescent antibody test for Leptospira spp. from liver, kidney, and urine were all negative. A heavy metal screen was performed in samples of liver and kidney with the following results:

|

Analyte |

Liver

|

|

|

Result |

Reference range |

|

|

Lead |

ND |

<1 |

|

Manganese |

1.8 |

2-4.4 |

|

Iron |

400 |

30-300 |

|

Mercury |

ND |

<1 |

|

Arsenic |

ND |

<4 |

|

Molybdenum |

ND |

<6 |

|

Zinc |

57 |

30-75 |

|

Copper |

867 |

25-100* |

|

Cadmium |

ND |

<2 |

|

Analyte |

Kidney

|

|

|

Result |

Reference range |

|

|

Lead |

ND |

<1 |

|

Manganese |

1.2 |

0.8-2.5 |

|

Iron |

800 |

30-200 |

|

Mercury |

ND |

<1 |

|

Arsenic |

ND |

<1 |

|

Molybdenum |

ND |

<2 |

|

Zinc |

43 |

20-40 |

|

Copper |

207 |

4-5.5* |

|

Cadmium |

ND |

<4 |

ND: not detected. All values are expressed in ppm on a wet-weight basis. *>250 ppm in liver and >15 ppm in kidney is consistent with copper toxicity.

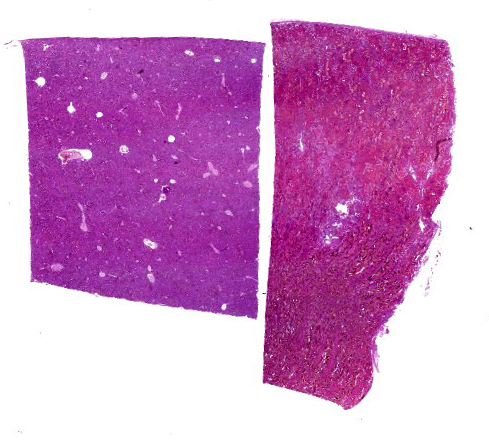

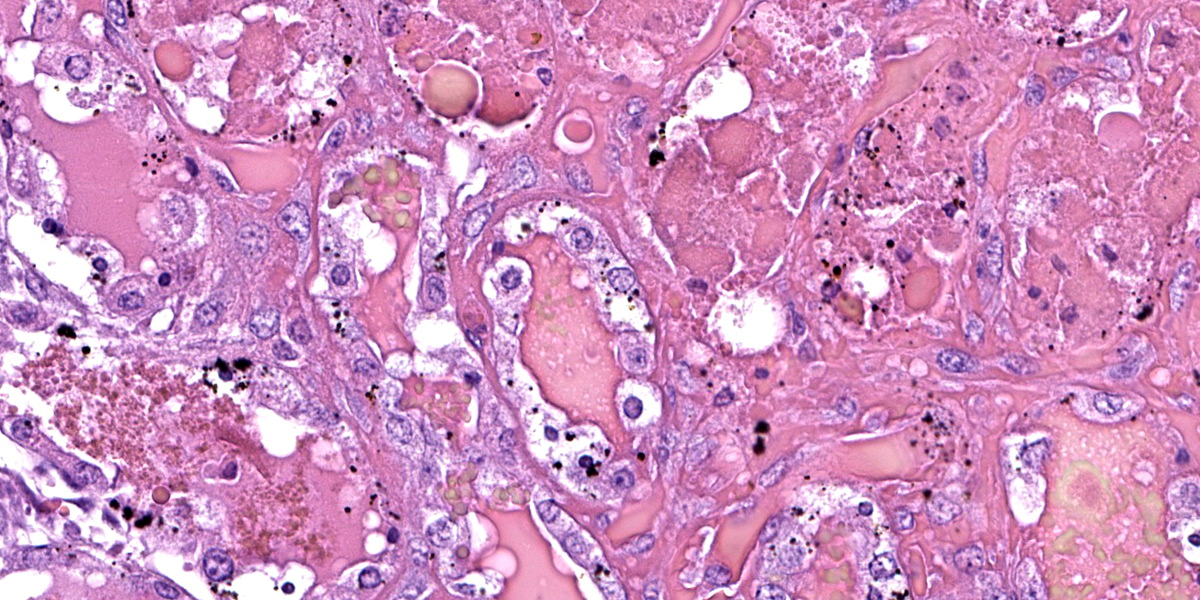

Microscopic Description:

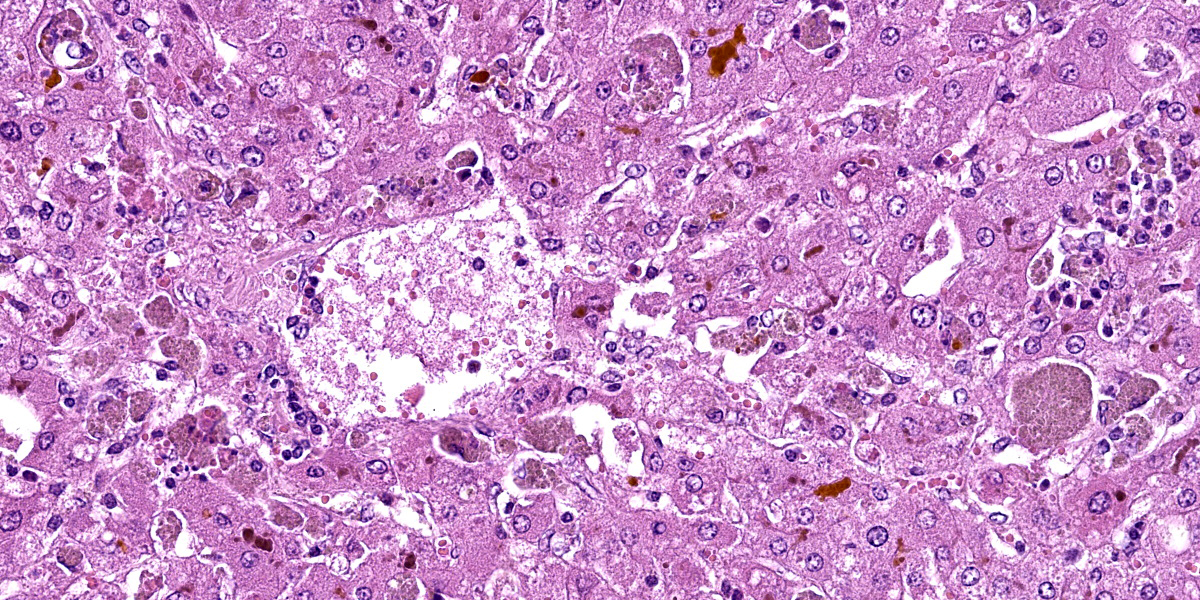

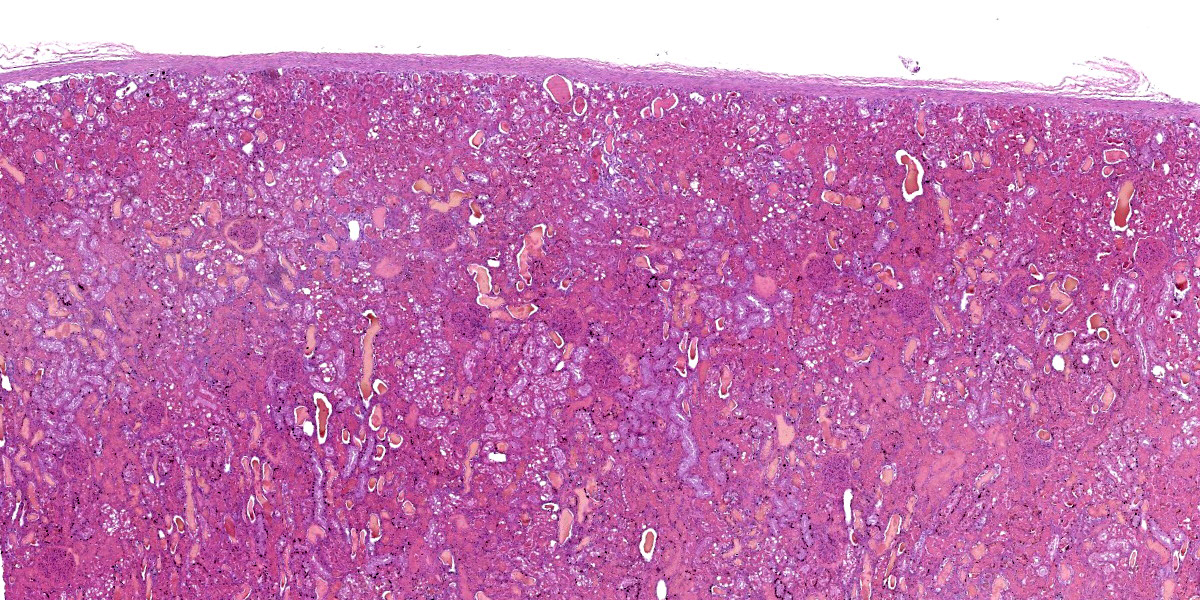

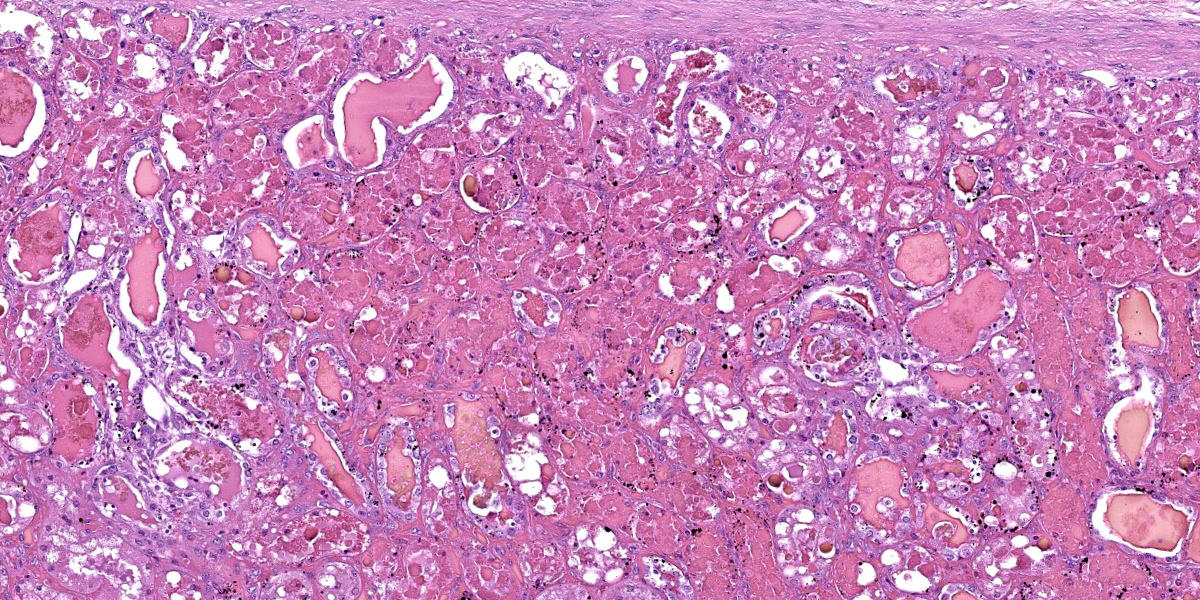

Liver: hepatocytes throughout centrilobular and midzonal areas exhibit swelling, poorly defined cell boundaries, and vesicular nuclei (degeneration) or have shrunken hypereosinophilic cytoplasm with angular borders and pyknotic nucleus or karyorrhexis (necrosis). Occasionally, necrotic hepatocytes are surrounded by aggregates of neutrophils, macrophages and extravasated erythrocytes. Hepatic cords are distorted, and hepatocyte orientation is altered, especially around the centrilobular regions. Scattered in the parenchyma many hepatocytes and Kupffer cells contain cytoplasmic, finely granular, brownish to gray material (interpreted as copper). Multifocally, a golden to orange amorphous pigment plugs the canaliculi (cholestasis). Portal regions are multifocally infiltrated by moderate numbers of pigment-laden macrophages and fewer lymphocytes.

Kidney: diffusely, cortical and medullary tubules, and glomerular filtration spaces are ectatic, and contain eosinophilic proteinic material/droplets and hyaline casts (consistent with hemoglobin). Cortical tubular epithelial cells exhibit a wide variety of changes including foamy cytoplasm, tumefaction, nuclear swelling (degeneration), attenuation, or hypereosinophilic cytoplasm with pyknosis (necrosis) frequently involving entire segments of the tubules (tubulorrhexis). Multifocally necrotic epithelial cells slough into the tubular lumen. Intracytoplasmic, coarse, granular, brown to black pigment (consistent with iron/hemosiderin) is widely distributed throughout the epithelium of the proximal tubules.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis, centrilobular to midzonal, acute, severe, diffuse, with intracytoplasmic granular material (consistent with copper) in Kupffer cells and hepatocytes, canalicular cholestasis, moderate, multifocal, neutrophilic and histiocytic hepatitis and portal hepatitis.

2. Kidney: Nephrosis (cortical tubular necrosis), acute, severe, diffuse with intratubular hyaline proteinic casts (consistent with hemoglobinuria) and intracytoplasmic brown to black pigment (consistent with iron/hemosiderin) in proximal tubular epithelial cells.

Contributor’s Comment:

The diagnosis of copper poisoning was based on macroscopic and histologic pathological findings which clearly indicated an acute hemolytic crisis coupled with markedly elevated copper concentrations in the kidney and liver. Considering the severity and extension of the lesions, death was attributed to renal and potential hepatic failure.

Copper is a heavy metal and an essential microelement. It acts on cells in different biochemical processes such as respiration, catecholamine biosynthesis, iron metabolism by copper-dependent enzymes, elastin and collagen formation, and melanin production.12

Chronic copper poisoning is frequent in sheep, and it has been reported in most sheep rearing regions all over the world.9 It may occur with daily intakes of 3.5 mg of copper/kg when grazing pastures that contain 15-20 ppm of copper (dry matter).5 Sheep are particularly susceptible to this condition because they are not able to increase copper biliary excretion as intake increases.7 Additionally, the protein that aids in the transport of copper in plasma (ceruloplasmin) possess a long half-life in sheep, thus increasing the time this mineral remains in the bloodstream.4 Although all ovine breeds are susceptible to copper poisoning, Texel sheep (as in this case) are among the most vulnerable.9

Chronic copper toxicosis is usually the result of an excessive copper intake for a prolonged period of time, often associated with contamination of water sources, pasture, or rations.1 Additionally, secondary factors such as low molybdenum, iron, or sulphate levels in the diet can increase copper absorption and accumulation in the liver. In this case, ingestion of red clover (Trifolium pratense) could have predisposed this animal to retain excessive copper as clover can have elevated copper:molybdenum ratios.5,10 Although molybdenum was not detected in liver and kidney of this sheep, the diet was not tested for molybdenum as would have been required to assess molybdenum intake.

Other factors including the ingestion of hepatotoxic plants such as those containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids (e.g. Senecio spp.) can induce copper release from damaged hepatocytes, resulting in increased blood levels of copper and risk of hemolytic crisis.1,5 To the best of our knowledge, the sheep in this flock were not exposed to hepatotoxic plants. Stress resulting from starvation, vigorous exercise, transportation, handling, and/or adverse weather conditions could elicit the hemolytic crisis typical of copper poisoning.5

When toxic quantities of copper are released into the bloodstream, intravascular hemolysis occurs due to a reduction of the antioxidant capacity of erythrocytes and lipid peroxidation of their cell membrane. The resulting hemoglobinemia ultimately leads to hypoxia and hemoglobinuric nephrosis.6,14

Carcasses usually exhibit diffuse yellow discoloration (jaundice) of the subcutaneous tissue, fat and mucosae.1,13 The liver can be enlarged and diffusely ochre/orange due to bile retention.1,5 The spleen is often enlarged, dark and soft.1,5 A black or dark red discoloration is present in the kidneys (colloquially referred to as gunmetal kidneys).5,13 The urine is also dark red, resembling port-wine due to hemoglobinuria.5,13

Differential diagnoses for acute jaundice and hemoglobinuria/hemoglobinuric nephrosis in sheep include bacterial diseases such as bacillary hemoglobinuria (Clostridium haemolyticum) and eperythrozoonosis (Mycoplasma ovis), parasitic diseases such as bovine theileriosis (Theileria lestoquardi, T. uilenbergior and T. luwenshuni) and babesiosis (Babesia ovis and B. motasi), and plant toxicoses (Allium cepa and Brassica spp.). In lambs, leptospirosis, yellow lamb disease (Clostridium perfringens type A), and type D enterotoxemia (C. perfringens type D) should be considered as well.3,8

Frequent histological findings of copper poisoning include centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis accompanied by pigment laden Kupffer cells.6,14 Rhodanine stain can be used to highlight intracellular copper. Portal mixed inflammatory infiltrates are also common.1,6 Renal lesions usually consist of acute tubular necrosis with intratubular eosinophilic casts.2,14 The deposition of iron-derived pigments in the cortical tubular epithelial cells, as seen in this case, has not been frequently described in the literature. However, a case presented in a previous Wednesday Slide Conference (Case 1, Conference 14, WSC 2010-2011) also described this finding. In our case, the heavy metal screen revealed that the iron levels in the kidney were markedly elevated, with a less significant elevation in the liver. It is possible that, as intravascular hemolysis progresses, heme iron is released into the plasma, filtered through renal glomeruli and captured by proximal renal tubules eventually leading to histologically visible iron deposits (hemosiderin), which could be highlighted using special stains such as Perl's Prussian blue.

Unequivocal confirmation of copper toxicity requires determination of toxic copper levels in blood (>1.5 µg/ml), kidney (>15 ppm, wet weight) and/or liver (>250 ppm, wet weight), although it should be stressed that hepatic levels may decrease after copper is released into the bloodstream during the hemolytic crisis.5,11

Contributing Institution:

Plataforma de Investigación en Salud Animal, Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria (INIA), La Estanzuela, Uruguay.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Necrosis, centrilobular, diffuse, mild, with cholestasis and intracytoplasmic pigment.

2. Kidney: Tubular degeneration and necrosis, acute, diffuse, severe, with hemoglobin and protein casts.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent case summary to accompany representative sections from the liver and kidney of this sheep. We agree that the changes in the kidney are severe, though the degree of necrosis within this section of liver is somewhat mild which surprised some participants. Possible explanations include slide/sampling variation as well as the notion that hepatocytes are able to extract oxygen from the portal vein with increasing efficiency during hypoxia. As such, they may be less immediately impacted by loss of erythrocytes/oxygen than the renal tubular epithelial cells supported by the vasa recta.

Conference participants discussed features of copper metabolism (or lack thereof) present within the liver. The large number of bile plugs (canalicular cholestasis) is accompanied by hepatocyte degeneration that is secondary to hypoxia and the growing anemic crisis. Together, these aspects highlight an increase in heme breakdown to biliverdin that is combined with the inability of hepatocytes to secrete bile constituents effectively. Rhodanine staining highlighted copper within hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, though iron staining was largely unremarkable despite the degree of hemolysis and elevated blood iron concentration in this case, likely attributed to intra- versus extravascular hemolysis. Masson’s trichrome showed some bridging fibrosis, though this is an expected and probably unrelated finding in an aged, grazing sheep, it is possibly indicative of the typical secondary hepatocyte injury, often plant toxicity, that initiates the cascade of hepatocyte death and copper release leading to hemolysis.

The changes in the kidney are classic in this case. We performed a Jones methenamine silver (JMS) and PAS stain to highlight the glomerular and tubular basement membrane – tubulorrhexis was not a feature of this case, however. We did not identify any copper within the kidney on rhodanine staining. Iron staining highlighted select renal tubular cells described by the contributor as containing hemosiderin; acid hematin is another differential to consider.

References:

- Cullen JM, Stalker M. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed., Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:258–352.

- García-Fernández AJ, Motas-Guzmán M, Navas I, María-Mojica P, Romero D. Sunflower meal as cause of chronic copper poisoning in lambs in southeastern Spain. Can Vet J. 1999;40:799–801.

- Giannitti F, Macias-Rioseco M, García JP, et al. Diagnostic exercise: hemolysis and sudden death in lambs. Vet Pathol. 2014; 51(3):624–627.

- Gooneratne SR, Buckley WT, Christensen DA. Review of Copper Deficiency and Metabolism in Ruminants. Can J Anim Sci. 1989;69:819–845.

- Gupta RK. A review of copper poisoning in animals: Sheep, goat and cattle. Int J Vet Sci Anim Husb. 2018;3:1–4.

- Hovda LR. Disorders caused by toxicants. In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine. 5th ed. St.Louis, MO: Mosby; 2015:1578–1616.

- López-Alonso M, Prieto F, Miranda M, Castillo C, Hernández J, Benedito JL. The role of metallothionein and zinc in hepatic copper accumulation in cattle. Vet J. 2005;169:262–267.

- Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016.

- McCaughley WJ. Inorganic and Organic Poisons. In: Aitken ID, ed. Diseases of Sheep. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 2007:424–439.

- Millar M, Errington H, Hutchinson JP, Norton A. Copper poisoning in sheep associated with clover. Vet Rec. 2007;161:108.

- Plumlee K. Metals and Minerals. In: Clinical Veterinary Toxicology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004:193–230.

- Radostits OM, Gay CC, Hinchcliff KW, Constable PD. In: Veterinary medicine: A textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. 10th ed. New York, USA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:1740-1741.

- Roubies N, Giadinis ND, Polizopoulou Z, Argiroudis S. A retrospective study of chronic copper poisoning in 79 sheep flocks in Greece (1987-2007). J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31:181–183.

- Villar D, Pallarés Martínez FJ, Fernández G. Retrospective study of chronic copper poisoning in sheep. An Vet Murcia. 2002;60:53–60.