Signalment:

6-month-old, male, domestic ferret (

Mustela putorius furo)This 6-month-old, male domestic ferret

presented to the referring veterinarian with a 1-2 week

history of diarrhea and lethargy. On physical exam, the

animal was assessed as being moderately dehydrated. The

abdomen was moderately distended. Abdominal ultrasound

showed marked enlargement of the spleen, multifocal areas

of hyperechogenicity in the liver, and markedly enlarged

mesenteric lymph nodes. Over the next week, diarrhea

continued and the ferret became anorexic, lost weight, and

developed a mild cough despite symptomatic treatment.

Euthanasia was elected and the animal was submitted to

the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health,

Lansing, MI for necropsy.

Gross Description:

On gross necropsy, the animal was

in fair to poor body condition with no visible fat stores and

increased prominence of bony protuberances. Dehydration

was marked as evinced by retraction of the eyes into the

orbits and tackiness of visceral surfaces. The abdomen

was prominently distended due to marked enlargement

of the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes. The spleen

was approximately 10 times normal size, dark black and

diffusely meaty. There were 7-8 relatively indistinct,

poorly circumscribed, pale white, semi-firm, nodular foci

dispersed throughout the splenic parenchyma. These foci

ranged from 0.5-1.5 cm in maximum diameter, and the

capsular surface of the spleen overlying few of these areas

was slightly raised. The liver was diffusely mottled dark

red and tan, and was mildly enlarged with slightly rounded

borders. There were 10-12 slightly raised, occasionally

coalescing, pale white, firm, slightly nodular plaques

ranging from 0.5-1 cm in diameter randomly distributed

on the capsular surface of the liver. The mesenteric lymph

nodes were markedly enlarged being approximately 5-8

times normal size. The capsular surfaces of lymph nodes

were irregular due to dozens of 2-5 mm in diameter,

slightly raised white nodules. On cut surface, the normal

nodal architecture was obliterated by pale tan to white, firm

tissue (

Fig. 3-1). The mesentery was irregularly thickened

by dozens of coalescing pale white, firm nodules and

irregular plaques. Similar white nodules and plaques were

segmentally distributed across the serosal surfaces of the

jejunum, ileum and to a lesser degree colon. In few areas,

sections of intestinal loops were adhered to each other

and to adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes by both fibrinous

and fibrous adhesions. The visceral pleural surfaces of

the lung were focally raised 1-3 mm by similar irregularly

shaped, pale white, poorly demarcated, firm plaques that

ranged from .2-1.5 cm in diameter. No other significant

lesions were noted grossly.

Histopathologic Description:

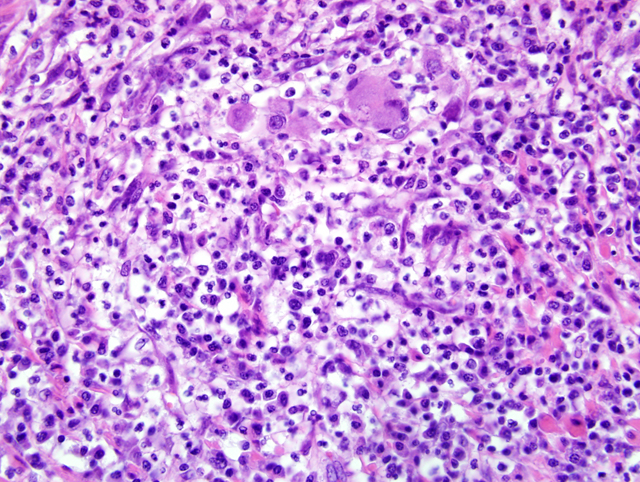

In the wall of the small intestine, there are multifocal to

coalescing areas of granulomatous to pyogranulomatous

inflammation. These areas are most prominent on the

serosal surfaces of the intestine, but also extend into the

underlying tunic muscularis and more rarely into the

submucosa and mucosa. Granulomas and pyogranulomas

are characterized by variable central necrosis and

infiltrates of degenerate neutrophils surrounded by

thick dense bands of plump epithelioid macrophages

and rare multinucleated foreign body type giant cells.

Varying rings of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and dense

maturing fibrosis surround granulomas. Granulomatous

inflammation is generally randomly distributed, but

occasionally is associated with vasculature. In sections of

lymph node, nodal architecture is expanded and ablated by

multifocal and coalescing granulomas and pyogranulomas

similar to those described in the small intestine (

Fig. 3-2).

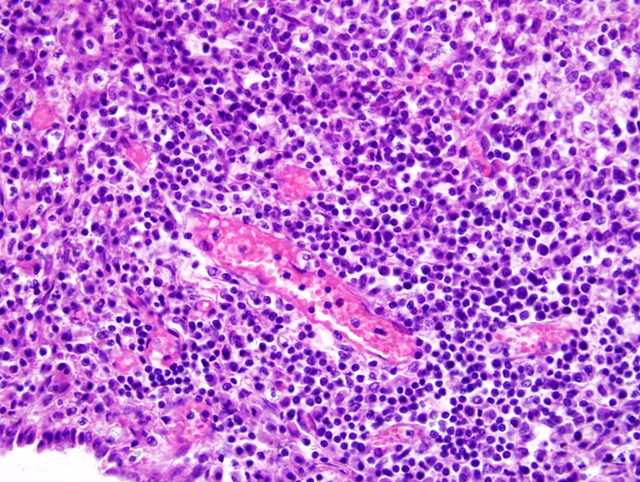

Granulomatous inflammation extensively extends through

the capsule into the surrounding perinodal adipose

tissue. Similar foci of granulomatous to occasionally

pyogranulomatous inflammation expand the serosal

surfaces of the liver and lung, and focally obliterate the

normal parenchyma of the lung and spleen. In rare areas,

the meninges overlying the cerebral cortex are expanded

by granulomatous inflammation. Vasculature within tissue

surrounding foci of granulomatous inflammation in the

liver, lung, and cerebral cortex is segmentally surrounded

by moderate cuffs of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and

fewer histiocytes (

Fig. 3-3). Immunohistochemistry

using a generic antibody against Group 1 coronaviruses

on sections of small intestine, lymph node, lung, and

spleen demonstrated strong positive, intracytoplasmic

immunoreactivity within macrophages at the center of

granulomas. A generic coronavirus RT-PCR yielded

amplification of a 650 base pair fragment. Sequencing

of this segment suggests that the amplified virus is

distinct from feline coronavirus (FeCoV). The amplified

virus appears to be most closely related to ferret enteric

coronavirus (FECV) that reportedly causes epizootic

catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small

intestine: Severe chronic segmental granulomatous to

pyogranulomatous enteritis and peritonitis

Lymph node: Severe chronic multifocal and coalescing

granulomatous to pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis

Lab Results:

PCR for Aleutian mink disease virus was negative.

Condition:

Coronavirus-associated granulomatous disease

Contributor Comment:

This case presentation

represents a disease that has been termed granulomatous

inflammatory syndrome (GIS) or ferret systemic

coronavirus infection (FSCV).1,4 This is an emerging

disease in ferrets that was first reported in the veterinary

literature in 2006 and closely resembles the clinical,

gross and microscopic features of feline infectious

peritonitis.

1,2,4

The exact etiopathogenesis of this lesion is unclear at this

point, but appears to be related to infection with a group

1 coronavirus. Immunohistochemistry using monoclonal

antibodies against feline coronavirus (FCoV) has been

reported to demonstrate immunoreactivity in macrophages

within lesions.

1,2 This antibody is not specific for FCoV

as it has been shown to detect other group 1 coronaviruses

including ferret enteric coronavirus (FECV) that has been

implicated as the cause of epizootic catarrhal enteritis

(ECE).

5,6 Electron microscopy confirmed the presence

of coronavirus-like particles within macrophages.

1 RTPCR

using primers that detect a broad array of group

1 coronaviruses yielded amplification of a 599bp

sequence that showed significant similarity to FECV

(77% homology) and to other group 1 coronaviruses.

1

Whether this virus represents a novel virus or variation

within an already described coronavirus is unclear. The

exact mechanism by which this virus causes the described

lesions is unknown. Further characterization of the virus

is required.

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Enteritis and peritonitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, moderate

Lymph node: Lymphadenitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, moderate

Conference Comment:

Coronaviruses are singlestranded

RNA viruses of major importance in domestic

animals.

3 Coronaviruses are currently split into 3

serogroups. Group 1 includes transmissible gastroenteritis

of swine (TGEV), canine coronavirus (CCV), feline

coronavirus (FCoV), and human coronavirus 229E.

Mouse hepatitis virus, sialodacryoadenitis of rats, turkey

coronavirus (bluecomb), and bovine coronavirus are the

major viruses recognized in group 2.

1,3 Group 3 comprises

the avian viruses and includes infectious bronchitis virus.

1,3

As the contributor mentioned, ferret systemic coronavirus

infection (FSCV) has an almost identical gross and

histologic appearance as FIP in domestic cats. Juvenile and

young adult ferrets seem to be the most susceptible to this

disease.(1) Gross lesions consist of widespread nodular

foci on multiple serosal surfaces that closely resemble

similar foci seen in clinical cases of FIP.

1 Involvement of

mesenteric lymph nodes is also reminiscent of FIP in cats.

FSCV closely resembles the dry form of FIP.

1 Histologic

lesions are identical to what is seen in cats with FIP and

consist of pyogranulomatous inflammation with vasculitis

and perivasculitis.

1 Relevant clinical pathologic findings

in these ferrets included a mild non-regenerative anemia

(anemia of chronic disease), thrombocytopenia and

hyperproteinemia.

1 The thrombocytopenia was attributed

to DIC secondary to vasculitis, while the hyperproteinemia

occurred due to hyperglobulinemia.

1

References:

1. Garner MM, Ramsell K, Morera N, Juan-Sall+�-�s C,

Jim+�-�nez J, Ardiaca M, Montesinos A, Teifke JP, L+�-�hr

CV, Evermann JF, Baszler TV, Nordhausen RW, Wise

AG, Maes RK, Kiupel M. Clinicopathologic features of

a systemic coronavirus-associated disease resembling

feline infectious peritonitis in the domestic ferret (

Mustela

putorius). Vet Pathol

45(2):236-46, 2008

2. Mart+�-�nez J, Ramis AJ, Reinacher M, Perpi+�-�+�-�n D.

Detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus-like antigen

in ferrets. Vet Rec

158:523, 2006

3. Murphy FA, Gibbs EPJ, Horzinek MC, Studdert MJ:

Coronaviridae.Â

In: Veterinary Virology, 3rd ed., pp. 495-

508. Academic Press, San Diego, California, 1999

4. Perpi+�-�+�-�n D, L³pez C. Clinical aspects of systemic

granulomatous inflammatory syndrome in ferrets (

Mustela

putorius furo). Vet Rec

162(6):180-185, 2008

5. Williams B, Kiupel M, West K, Raymond JT, Grant

CK, Glickmann LT, Coronavirus associated enzootic

catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets (

Mustela putorius furo):

a review of 120 cases (1993-1998) JAVMA 217: 526-530,

2000

6. Wise AG, Kiupel M, Maes RK. A novel coronavirus

associated with epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in

ferrets. Virol

349:164-174, 2006