Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 14, Case 1

Signalment:

Adult male limousine bull, (Bos taurus)

History:

Unknown.

Gross Pathology:

Post-mortem examination revealed:

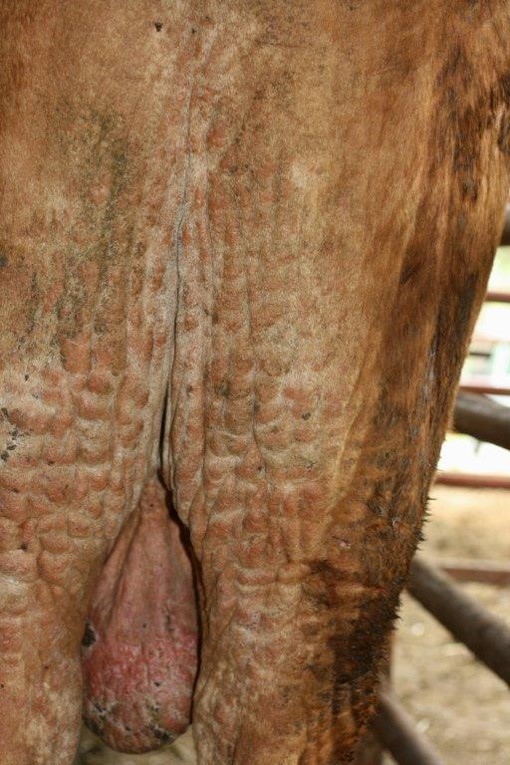

- Diffuse alopecia and lichenification and multifocal erythematous nodules (Fig. 1)

- Multifocal granulomatous scleritis and conjunctivitis (Fig. 2)

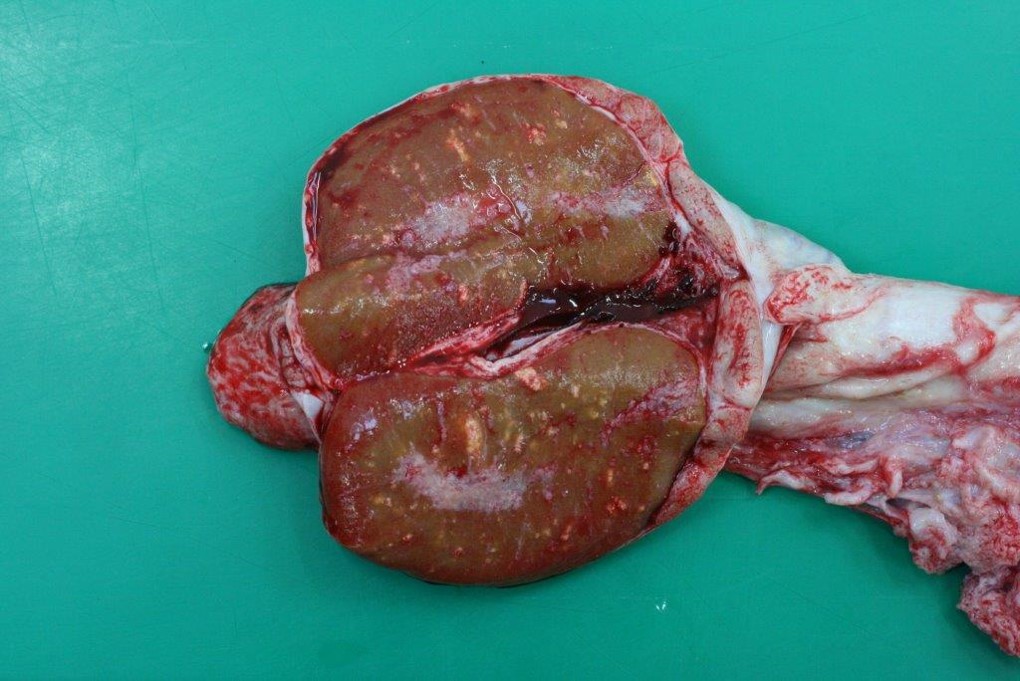

- Multifocal granulomatous orchitis (Fig. 3)

No other macroscopic lesions were present.

Microscopic Description:

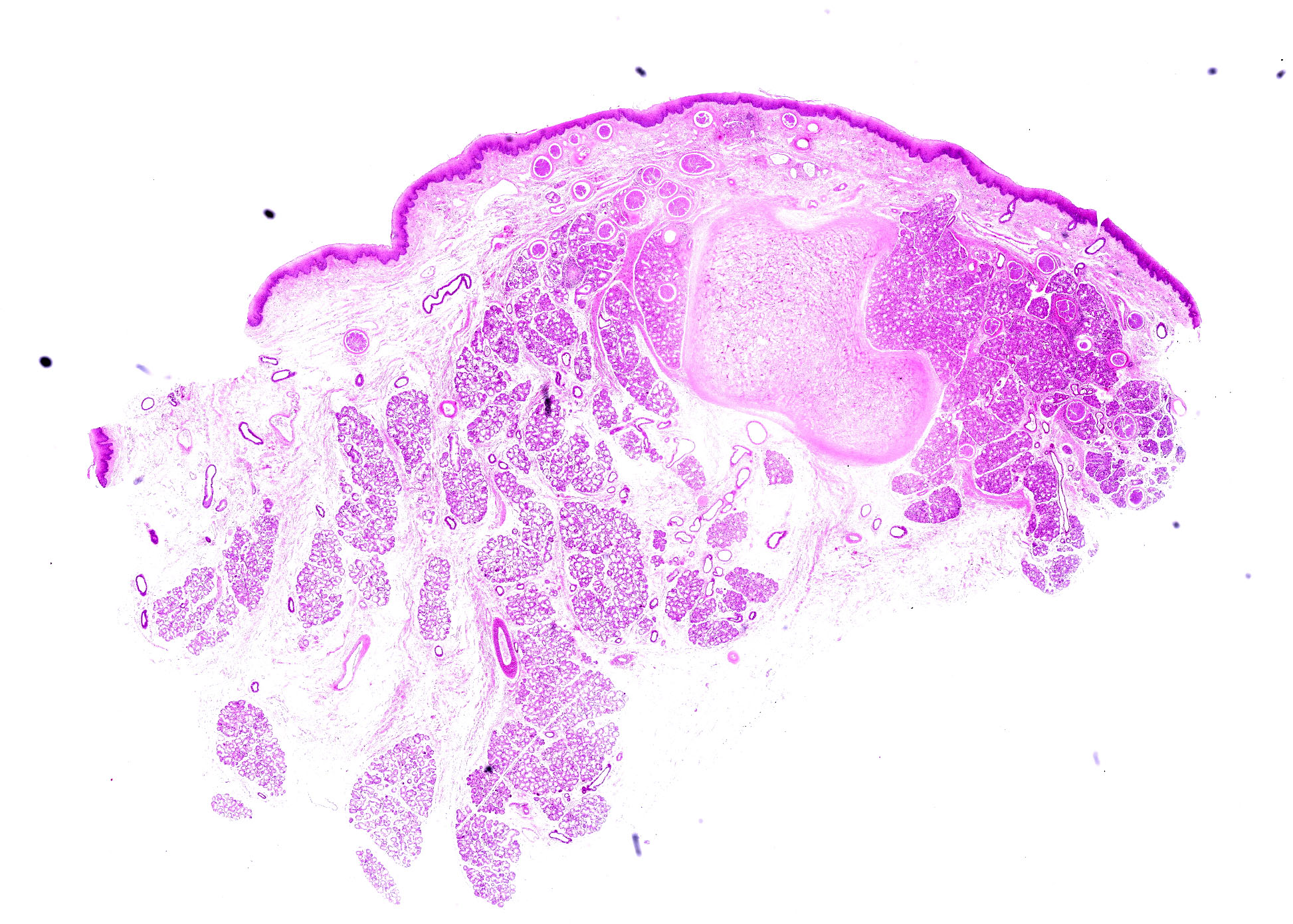

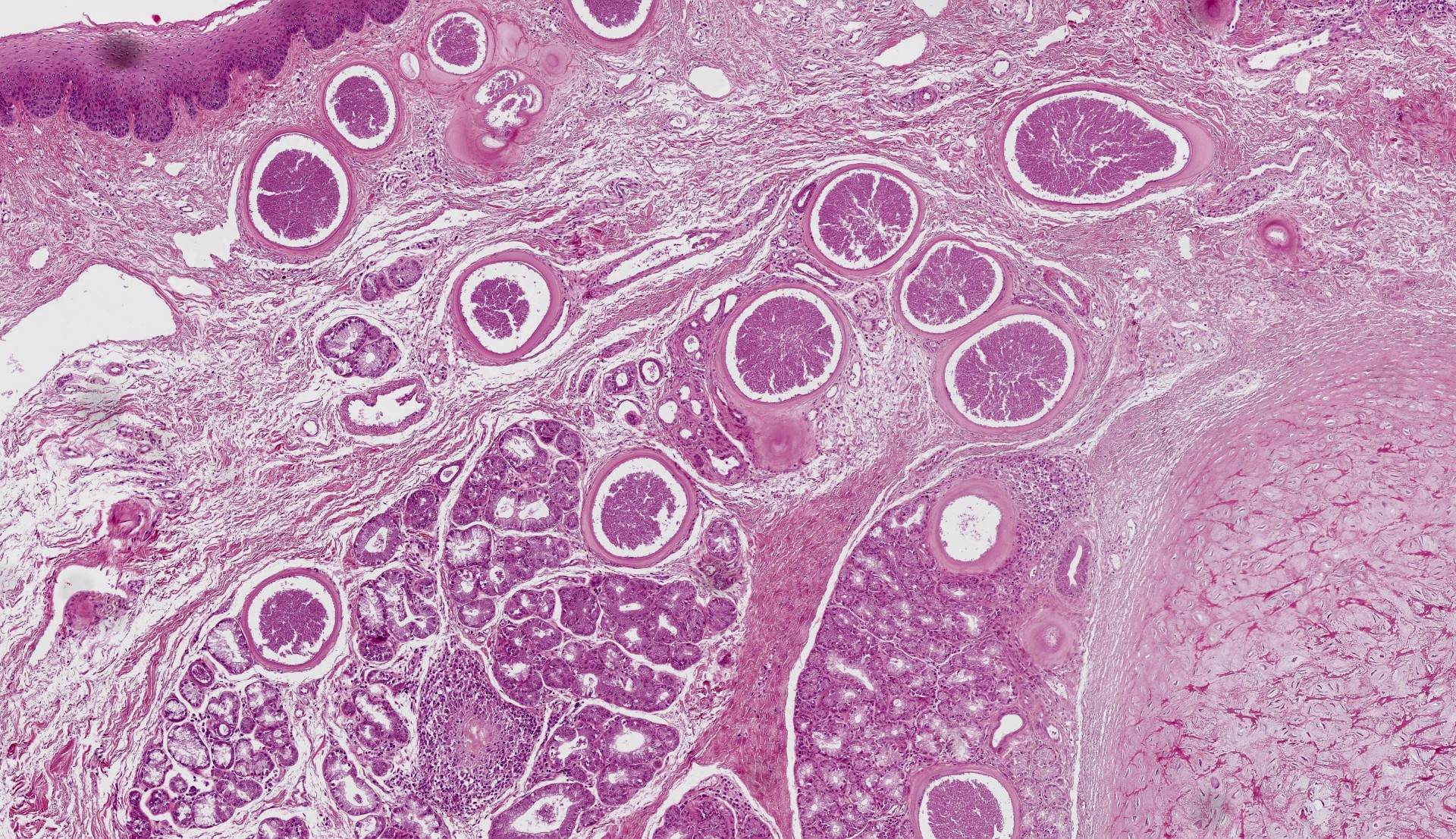

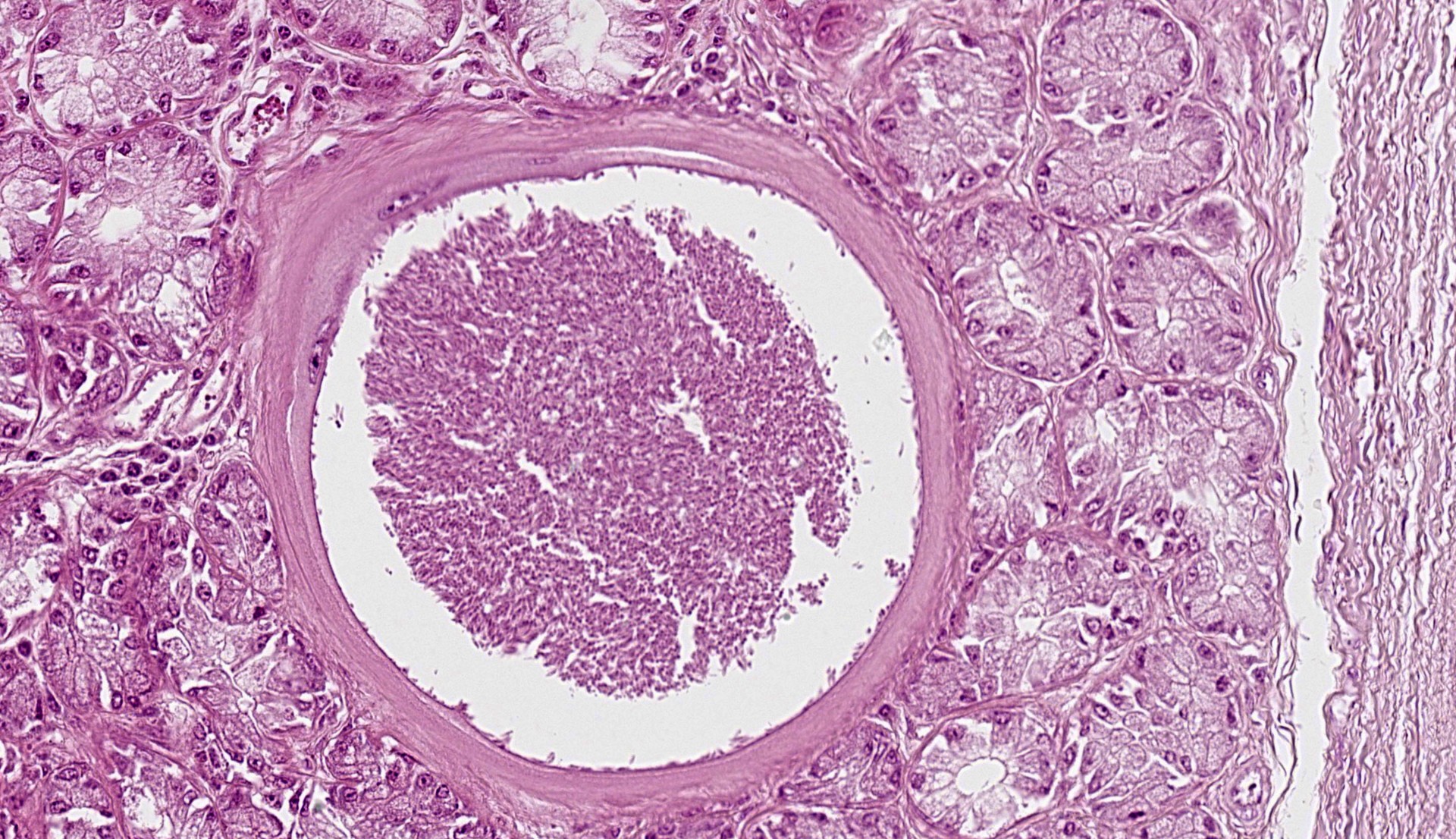

Epiglottis: Multifocally, in the lamina propria and within the mucous gland interstitial tissue, a moderate number of round, 400µm in diameter, protozoal cysts are visible. Cysts are composed of a multilayer wall; the following wall parts are recognizable: an external fibrillary host ‘collagen layer; a thick, homogenous eosinophilic outer layer; and a thin inner layer composed host cell cytoplasm, containing multiple flattened nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The parasitophorous vacuole within the host’s cell cytoplasm is 250µm in size, and contains a large number of densely packed, 3-5 µm crescentic bradyzoites (Figure 4). The inflammation around the cysts is almost absent or minimal, and mainly composed of macrophages.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Epiglottis: epiglottitis, granulomatous, multifocal, minimal, with moderate number of protozoal cysts; etiology consistent with Besnoitia besnoitii, bovine.

Contributor’s Comment:

Besnoitia spp are obligatory intracellular apicomplexan protozoal parasites belonging to the Sarcocystidae family. Several species have been identified, affecting both wild and domestic animals. (Table 1)

Besnoitia besnoiti is the causative agent of bovine besnoitiosis. The parasite is present worldwide. Bovine besnoitiosis has an outsized economic impact because of mortality, which can reach up to 10% of clinically infected animals in Africa. Similarly, poor body condition of surviving animals may result in culling or decreased market value.6 The disease presents seasonal variations, but this does depend on the geographical region of affected animals.6,8 Sex predisposition is also variable;8 young adults are more affected by the severe clinical forms than animals of less than 18 months or older than 4 years.6

The life cycle of Besnoitia is known only for 4 species, for which felidae were recognized as the definitive host.5,8 For the other instances which include Besnoitia besnoitii, the definitive host, mode of transmission, and pathogenesis are not completely understood.8 In the species for which life cycle is known, the parasite is located in the intestine and the sporulated oocysts are released with feces. The exact mode of transmission is unknown, though blood-sucking insects and direct transmission between intermediate hosts are considered possible routes.6,8 In the first phase of intermediate host infection, tachyzoites replicate in endothelial cells, monocytes, and neutrophils. They then move into peripheral tissues where they invade fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, and/or smooth muscle cells and form bradyzoite-containing cysts. This intracellular replication induces profound changes in the hosting cell with development of parasitic cysts. The definitive host is infected by ingesting cysts containing tissues.8

Bovine besnoitiosis has acute, subacute and chronic phases. In the acute phase, tachyzoites replicate within endothelial cells, causing vasculitis and thrombosis. Clinically, fever, anorexia, rhinitis, conjunctivitis and photophobia, subcutaneous edema and peripheral lymph node hypertrophy can be observed. In the subacute phase, tachyzoites move to peripheral tissues and invade mesenchymal cells. Small cysts can be seen in the sclera, and chronic dermatitis starts to develop. The chronic form is linked to cysts maturation and eventually associated inflammation.

Chronic dermatitis with alopecia and lichenification are often present and they can be aggravated by secondary cutaneous bacterial and fungal infections. Sterility, due to previous inflammatory reaction and vasculitis in the testis, can also be observed.2,3,6

Acute besnoitiosis is difficult to diagnose, while in chronic cases the histologic evidence of intra-cellular cysts is pathognomonic.4 Today, no treatments exists.6

Grossly and histologically, the most affected organs are skin, upper respiratory mucosae, sclera and conjunctiva, and muscular and testicular connective.2,6 Cysts can measure up to 0.5mm, being visible as small nodules at naked eye.1,8

Histologically, in the acute phase, moderate perivascular infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages and eosinophils are present in the dermis. Dermal edema is a consistent finding though hemorrhages are variable. Few tachyzoites can be visible in parasitophorous vacuoles within endothelial cells: they have a crescentic shape with an eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nevertheless, they can be better identified by immunohistochemistry.4

In the subacute and chronic phases, edema and vascular lesions regress and cysts form. Cyst development is characterized by an increase in intracellular zoite number, host cell modifications (including increase in size, multinucleation, anisokaryosis, and prominent nucleoli) and development of a cyst wall. At the end of their maturation (34-50 days post seroconversion), cysts can be up to 400µm in size, and their size is correlated to their age.1,4 The cyst wall is formed by 4 layers comprising an outer condensed collagen layer, an eosinophilic 30µm thick layer, a thin homogenous basophilic layer (not always visible, especially in older cysts), and a rim composed of scant cytoplasm containing multiple enlarged nuclei. The multilayer wall lines a parasitophororus vacuole containing many basophilic bradyzoites.4 The inflammatory reaction is almost absent however. When present, especially secondary to cyst ‘rupture, it is composed of macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells with few eosinophils. In the skin, cysts are mainly located in the papillary dermis.1,4,8

Table 1.

Contributing Institution:

www.vetagro-sup.fr

JPC Diagnosis:

Epiglottis: Epiglottitis, granulomatous, multifocal, mild, with apicomplexan cysts.

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Corrie Brown from the University of Georgia who focused on infectious and transboundary diseases with conference participants. Although the Wednesday Slide Conference archives are (thankfully perhaps) not replete with Foreign Animal Disease examples, Dr. Brown nonetheless selected four cases to delve into comparative pathogenesis.

In this first case, the contributor lays out a nice background of Besnoitia with several interesting gross images. Conference participants were not entirely sure of tissue identification for the submitted histologic image, though the presence of tissue cysts, their predilection for the epiglottis, and a large wedge of cartilaginous tissue were helpful landmarks. Bradyzoites within tissue cysts were readily apparent on H&E alone, though PAS was similarly useful. In some smaller cysts, cell nuclei were still visible and peripheralized by parasitophorous vacuoles containing bradyzoites. Although not stated by the contributor, the presence of cysts within both connective tissue and glands suggests that one or more of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, or endothelial cells were the site of tachyzoite replication in this case.

Similar to other emerging diseases, Besnoitia has been increasingly identified within European cattle, to include further northern locations such as Ireland.9 As biting insects may play a role in the transmission of these protozoans, both prolonged periods of warmer temperatures and extreme temperatures due to global climate change likely aid in sustained development and dispersion of Stomoxys and Tabanus.

Dr. Brown emphasized the viewpoint of small-scale animal agriculture (i.e. ‘smallholders’10) and the stakes at play in transboundary diseases. As each individual animal may represent significant economic value from production of meat, milk, and/or fiber, the impact of Besnoitia can be felt several times over. Though death is the most severe loss for smallholders of affected animals, loss of productivity (meat, milk) as well as poor quality hide in surviving animals is also a loss of income. Likewise, permanent infertileity of bulls may rob smallholders of a prosperous future. Therefore, understanding and control of these diseases plays an important role in global food security and overall stability.

References:

- Diezma-Díaz C, Tabanera E, Ferre I, et al. Histological findings in experimentally infected male calves with chronic besnoitiosis. Vet Parasitol. 2020 May 1;281:109120.

- Gentile A, Militerno G, Schares G, et al. Evidence for bovine besnoitiosis being endemic in Italy—First in vitro isolation of Besnoitia besnoiti from cattle born in Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2012 Mar 23;184:108–115.

- González-Barrio D, Diezma-Díaz C, Tabanera E, et al. Vascular wall injury and inflammation are key pathogenic mechanisms responsible for early testicular degeneration during acute besnoitiosis in bulls. Parasit Vectors. 2020 Mar 2;13:113.

- Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Majzoub-Altweck M, Scharr JC, Schares G, Hermanns W. Naturally Acquired Bovine Besnoitiosis: Histological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Disease. Vet Pathol. 2015 May 1;52:476–488.

- Schares G, Joeres M, Rachel F, et al. Molecular analysis suggests that Namibian cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) are definitive hosts of a so far undescribed Besnoitia species. Parasit Vectors. 2021 Apr 14;14:201.

- Schulz KCA. A report on naturally acquired Besnoitiosis in bovines with special reference to its pathology. :16.

- Verma SK, Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Murata FHA, Lovallo MJ, Rosenthal BM, Dubey JP. Bobcats (Lynx rufus) are natural definitive host of Besnoitia darlingi. Vet Parasitol. 2017 Dec 15;248:84–89.

- Besnoitiosis. In: Vol. 1, Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. W B Saunders Co Ltd; 2015:2456.

- Ryan EG, Lee A, Carty C, O'Shaughnessy J, Kelly P, Cassidy JP, et al. Bovine besnoitiosis (Besnoitia besnoiti) in an Irish dairy herd. Vet Rec. 2016;178:608–608.

- Lifestock International. About Us. https://lifestock.org/