Signalment:

Approximately 9-year-old male mudpuppy (

Necturus maculosus)Keepers reported this mudpuppy, a collection animal at the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, to the veterinary

staff for acute coelomic distention and floating upside-down. On physical exam, the animal was dull but responsive,

and had gained approximately 250g since its most recent weight check. Ultrasound exam revealed a large amount of

free fluid within the coelomic cavity, while the heart, liver, and intestines all appeared to be within expected limits.

The coelomic fluid had low specific gravity, 1.009, and cytologic examination of a concentrated sample showed

many lymphocytes and presumptive granulocytes, as well as a single, septate, branching fungal hypha. Treatment

was initiated, including twice daily coelomocentesis, ceftazidime (20mg/kg q72h), and once daily baths in

intraconazole and Wright-Whitaker solution. On the fourth day of treatment, the animal was found moribund and

floating upside-down. Shortly thereafter, the heartbeat could not be detected by Doppler.

Gross Description:

On necropsy, there were multiple variably-sized areas of light red discoloration on the skin of the

ventrum and around the cloaca (livor mortis). The musculature of the body wall was diffusely gelatinous on

palpation (edema). Approximately 10mL of colorless, slightly turbid fluid was present within the coelomic cavity.

The liver was predominantly brownish black with subtle, multifocal, light tan mottling of the capsular surface. The

testes and kidneys appeared mottled light tan to dark brown. All other major organs were grossly unremarkable.

Histopathologic Description:

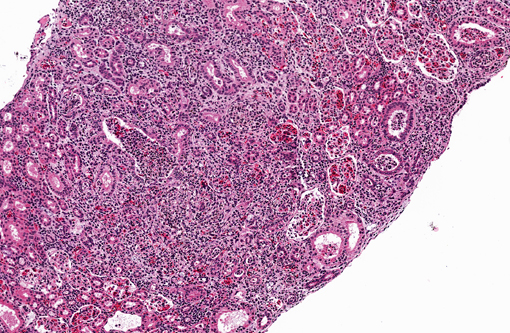

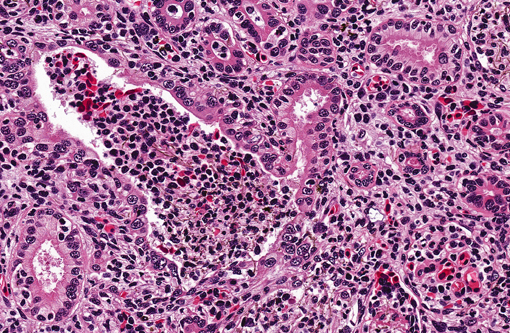

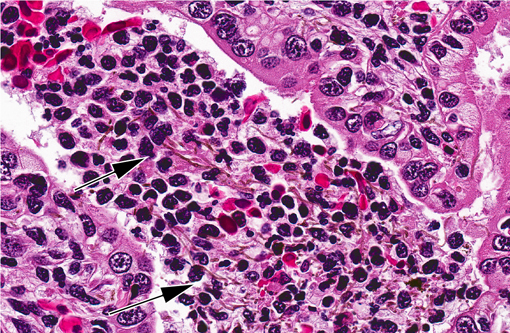

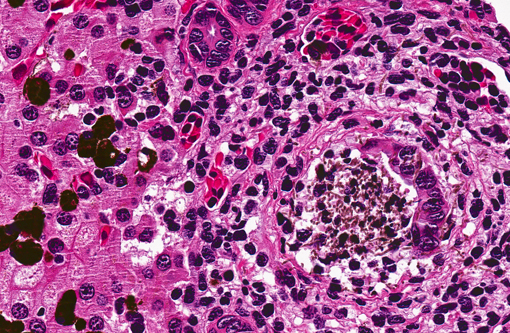

Kidney. Multifocally infiltrating the interstitium and tubules is an

inflammatory cell population consisting primarily of cells with large, multilobulated nuclei (neutrophils) and fewer

cells with large, round to reniform nuclei (macrophages). Admixed with the inflammatory cells are variable amounts

of fibrin, necrotic cellular debris, extravasated red blood cells (hemorrhage), and numerous slender, 5-7μm diameter,

septate fungal hyphae characterized by light brown pigment and acute angle dichotomous branching. Tubules are

occasionally dilated and contain low numbers of red blood cells and viable and degenerating leukocytes.

Liver. The periportal areas are infiltrated by moderate numbers of macrophages and scattered neutrophils, admixed

with occasional fragments of pigmented fungal hyphae. Portal areas consistently contain four or more bile ductules

(biliary hyperplasia). There are moderate numbers of clustered and individual melanomacrophages scattered

throughout the hepatic parenchyma.

** Some slides also contain sections of testes, which display inflammation and necrosis similar to that observed in

the kidney sections.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Kidney, tubulointerstitial nephritis, neutrophilic and histiocytic, multifocal, subacute, severe, with necrosis, and intralesional pigmented fungal hyphae

2. Liver, hepatitis, periportal, histiocytic and neutrophilic, multifocal, subacute, moderate, with biliary hyperplasia, and intralesional pigmented fungal hyphae

Lab Results:

Fungal culture of the coelomic fluid yielded 2+

Exophiala species. Further speciation was not

provided. There was no growth on aerobic bacterial culture.

Condition:

Phaeohyphomycosis

Contributor Comment:

Death of this mudpuppy was attributed to phaeohyphomycosis, a condition characterized

by the presence in tissues of pigmented, or dematiaceous, hyphae, pseudohyphae, yeasts, or any combination of

these forms.(12) Phaeohyphomycosis, which can be caused by over one hundred different types of pigmented fungi,

encompasses a wide spectrum of opportunistic mycoses in humans and domestic animals, reports of which range

from superficial cutaneous infection to fatal encephalitis.(1,2,5,6,12) Similarly, in amphibians, the disease may be limited

to ulcerative or granulomatous lesions of the skin, or be disseminated systemically.(4) The term phaeohyphomycosis

should not be confused with chromoblastomycosis, which refers specifically to a localized cutaneous or

subcutaneous pigmented fungal infection characterized by the presence of rounded sclerotic bodies.(12)

Fungal culture of the mudpuppys coelomic fluid yielded growth of a black mold morphologically consistent with an

Exophiala species. As with other dematiaceous fungi,

Exophiala is widely distributed in soil, decaying vegetation,

and water. Species of

Exophiala are notoriously difficult to classify and identify due to their complicated life cycles

and morphologic plasticity, and recently molecular diagnostic tools have become important in defining the

taxonomy of the group.(13,14 )It has been reported as an emerging opportunistic pathogen in both immunocompetent

and immune suppressed people,(14) including solid organ transplant recipients.(3,11)

Exophiala species are significant

pathogens in a variety of fresh and saltwater fish including salmon,(8) flounder,(10) and sea dragons.(13)

Infection with dematiaceous fungi is typically initiated by introduction of the agent via an abrasive or penetrating

wound, or by inhalation of fungal elements from the environment.(12) In this case, the presence a large mat of

interwoven fungal hyphae within the central air space of one lung, and the lack of visible external wounds, were

compatible with inhalation being the route of entry.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney: Nephritis, tubulointerstitial, pyogranulomatous, diffuse, moderate, with numerous pigmented fungal hyphae.

2. Liver: Hepatitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal, mild to moderate, with rare pigmented fungal hyphae.

Conference Comment:

Dematiaceous fungal hyphae are septate, 2-8 um wide, and have non-parallel pigmented

walls and random dilated, round, thick walled segments up to 25 um in diameter that resemble chlamydospores or

chlamydoconidium. Fungi grow in tissue as yeast, pseudohyphae and hyphae and may be extracellular and

intracellular. Organisms that cause chromoblastomycosis, a condition mentioned by the contributor, are pigmented,

but do not form hyphae in tissue, and their division by septation is distinctive. Additionally, they form large 4-15

um, round, thick and dark-walled yeast-like cells, known as sclerotic bodies or muriform cells(9).

There was some slide variation, and some sections had large hyphal mats within the ureter. This feature, along with

the unusual and striking amount of inflammation within Bowmans space, interpreted as reflux tubulitis, led

conference participants to consider an ascending infection.

References:

1. Anor S, Sturges BK, Lafranco L, Jang SS, Higgins, RJ, Koblik PD, LeCouteur RA. Systemic phaeohyphomycosis (

Cladophialophora bantiana) in a dog clinical diagnosis with stereotactic computed tomographic-guided brain biopsy.Â

Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2001;15:257-61.

2. Bouljihad M, Lindeman CJ, Hayden DW. Pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis associated with dematiaceous fungal (

Cladophialophora bantiana) infection in a domestic cat.Â

Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2002;14:70-72.

3. Fothergill, AW. Identification of dematiaceous fungi and their role in human disease.

Clinical Infectious Disease. 1996; 22(Suppl2):S179-84.

4. Genovese LM, Whitebread TJ, Campbell CK. Cutaneous nodular phaeohyphomycosis in five horses associated with

Alternaria alternata infection. Veterinary Record. 2001;148:55-56.

5. Herrae P, Rees C, Dunstan R. Invasive phaeohyphomycosis caused by

Curvularia species in a dog.Â

Veterinary Pathology. 2001;38:456-59.

6. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by fungi. In:

Veterinary Pathology, eds. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW, 6th ed., p. 530. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland, 1997

7. Kurata P, Munchan C, Wada S, Hatai K, Miyoshi Y, Fukuda Y. Novel Exophiala infection involving ulcerative skin lesions in Japanese flounder

Paralicthys olivaceous. Fish Pathology. 2008;43(1):35-44.

8. Lief MH, Caplivsky D, Bottone EJ, Lerner s, Vidal C, Huprikar S. Exophiala jeanselmei infection in sold organ transplant recipients: report of two cases and review of the literature.Â

Transplant Infectious Disease. 2011;13:73-79.

9. Nyaoke A, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis in weedy seadragons (

Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) and leafy seadragons (

Phycodurus Eques) caused by species of

Exophiala, including a novel species.Â

Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2009;21:69-79.

10. Otis EJ, Wolke, RE. Infection of

Exophiala salmonis in Atlantic Salmon (

Salmo salar L.) Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1985;21(1):61-64.

11. Pena-Penabad C, Duran MT, Yebra MT, Rodriguaz-Lozano J, Vieirra V, Fonseca E. Chromomycosis due to

Exophiala janeselmie in a renal transplant recipient.Â

European Journal of Dermatology. 2003;13(3):305-7.

12. Schell WA, Salkin IF, McGinnis MR. Bipolaris, Exophiala, Scedosporium, Sporothrix, and other dematiaceous fungi. In: Murray PR, Barron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Yolken RH, eds.Â

Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8th ed. Washington, DC. ASM Press. 2003:1820-29.

13. Taylor SK. Mycoses. In: Wright KM, Whitaker, BR, eds.Â

Amphibian Medicine and Captive Husbandry. Malibar, FL. Krieger Publishing Company. 2001:187-188

14. Zeng JS, De Hoog GS.Â

Exophiala spinifera and its allies: diagnostics from morphology to DNA barcoding.Â

Medical Mycology. 2008;46:193-208.