CASE IV: 20-21 345 (JPC 4153945-00)

Signalment:

13-year-old, female, rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta).

History:

This rhesus monkey has a two-year history of severe menses. The monkey would become pale, quiet, lethargic and hyporexic during these periods. Subcutaneous fluids and other supportive care were provided during these periods and ultimately the animal would recover over the course of a few weeks. During the monkey's last month, she began to rapidly decline, in the absence of menses, which was characterized by decreased activity/recumbency in her cage, and weight loss where she would no longer take treats from staff. Ultimately euthanasia was elected due to the clinical decline of the animal.

Gross Pathology:

No gross description or images were provided by the clinical veterinarians. Their working diagnosis was endometriosis and they submitted a sample of uterus and mesenteric mass for confirmation.

Laboratory results:

Comprehensive CBC 6 months prior to euthanasia was consistent with a hypochromic and macrocytic regenerative anemia. Clinically this was attributed to iron deficiency affiliated with chronic blood loss.

|

CBC Parameters |

|

|

WBC (k/ul) |

9.41 |

|

RBC (M/uL) |

3.30 |

|

HGB (g/dL) |

9.6 |

|

HCT (%) |

33.9 |

|

MCV (fL) |

103 |

|

MCH (g/pg) |

29.1 |

|

MCHC (g/dL) |

28.3 |

|

Platelet Count (K/uL) |

361 |

|

RBC Morphology |

|

|

Reticulocyte (%) |

18.4 |

|

Absolute Reticulocyte (K/uL) |

607 |

|

Nucleated RBC (/100 RBC) |

25 |

|

Polychromasia |

Moderate |

|

Anisocytosis |

Moderate |

|

Poikilocytosis |

Moderate |

|

Heinz bodies |

None seen |

|

Differential Absolutes |

|

|

Neutrophils (/uL) |

5358 |

|

Bands (/uL) |

0 |

|

Lymphocytes (/uL) |

2820 |

|

Monocytes (/uL) |

1222 |

|

Eosinophils (/uL) |

0 |

|

Basophils (/uL) |

0 |

|

WBC corrected for the presence of nucleated RBC's1 |

|

Microscopic Description:

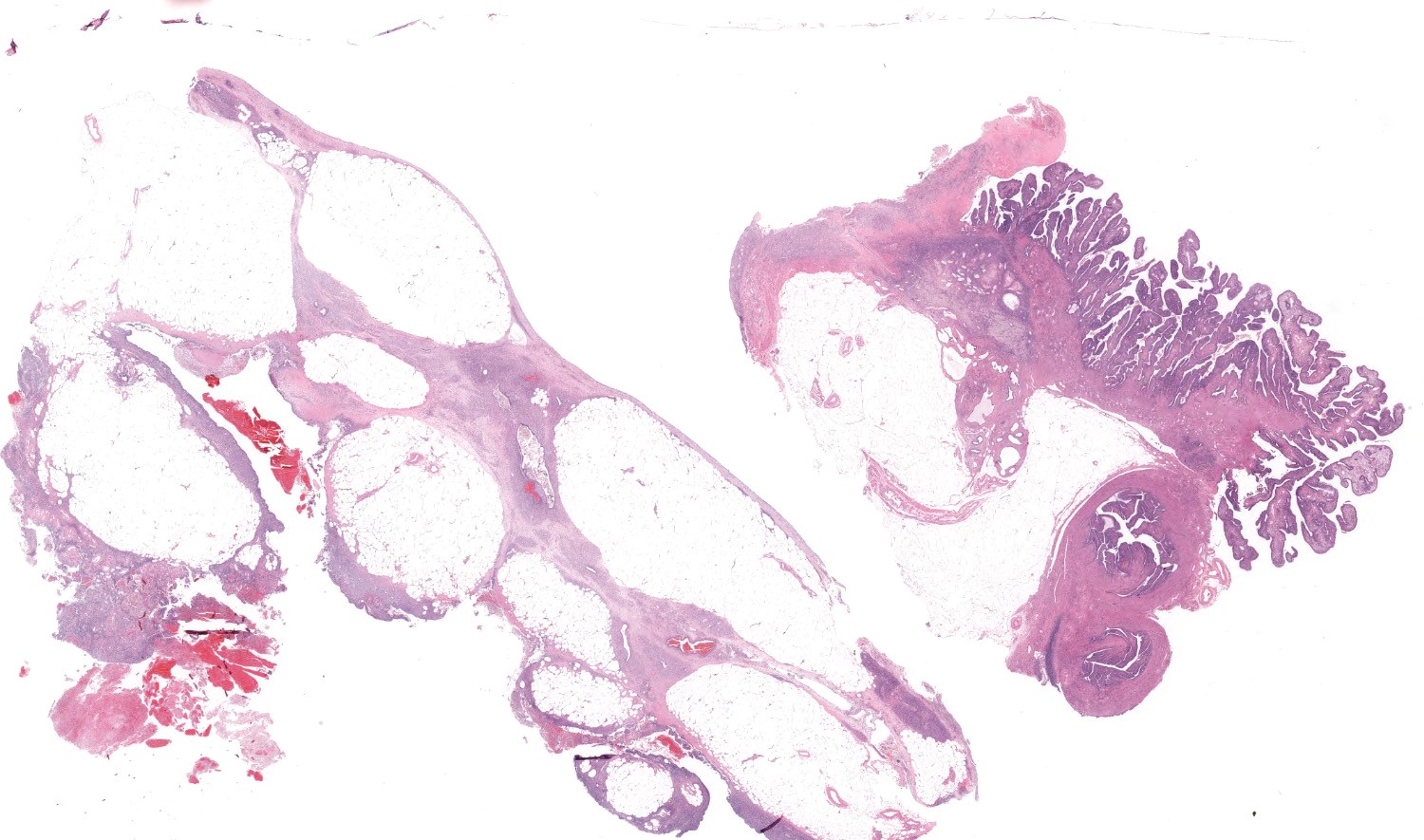

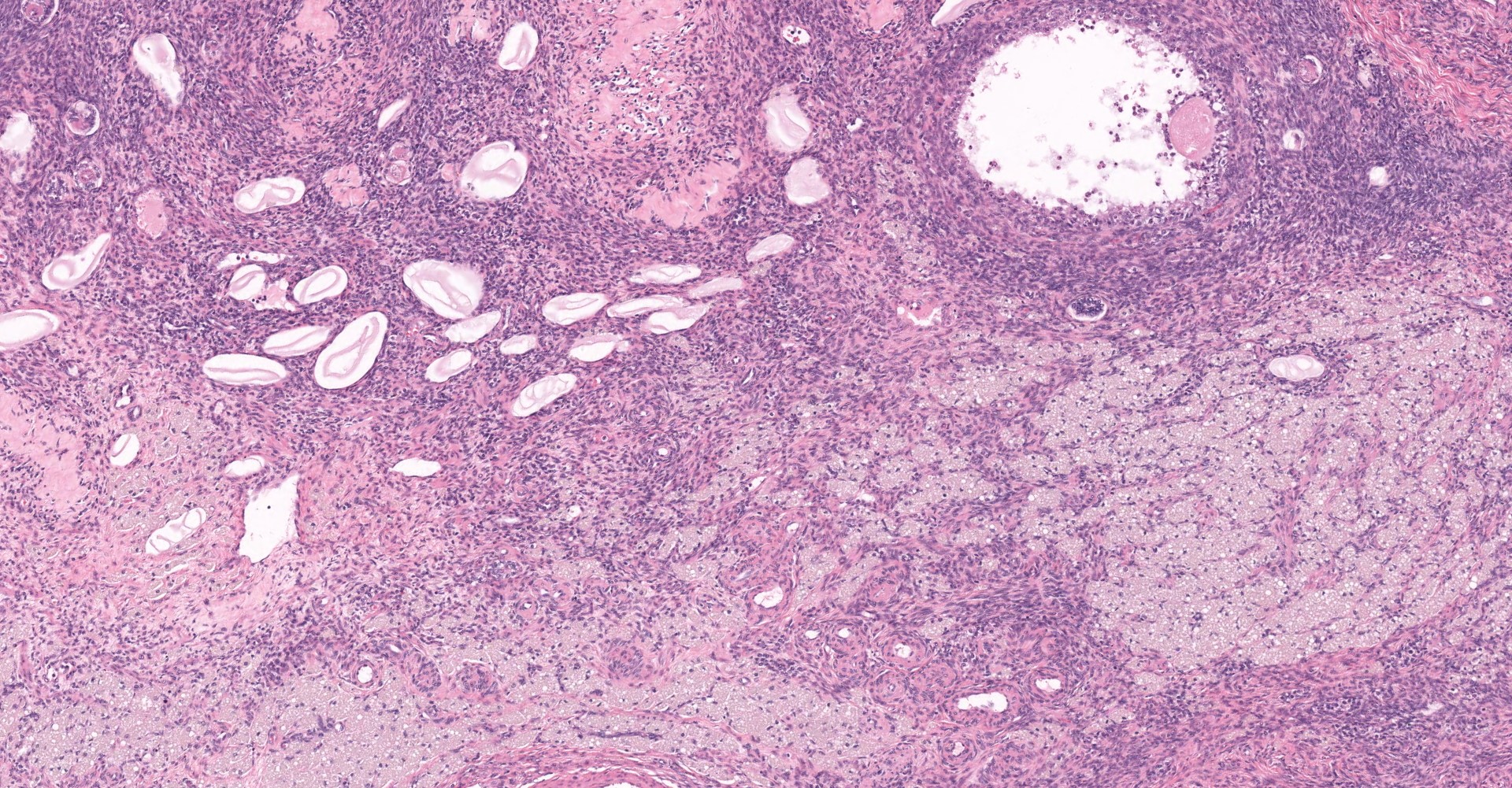

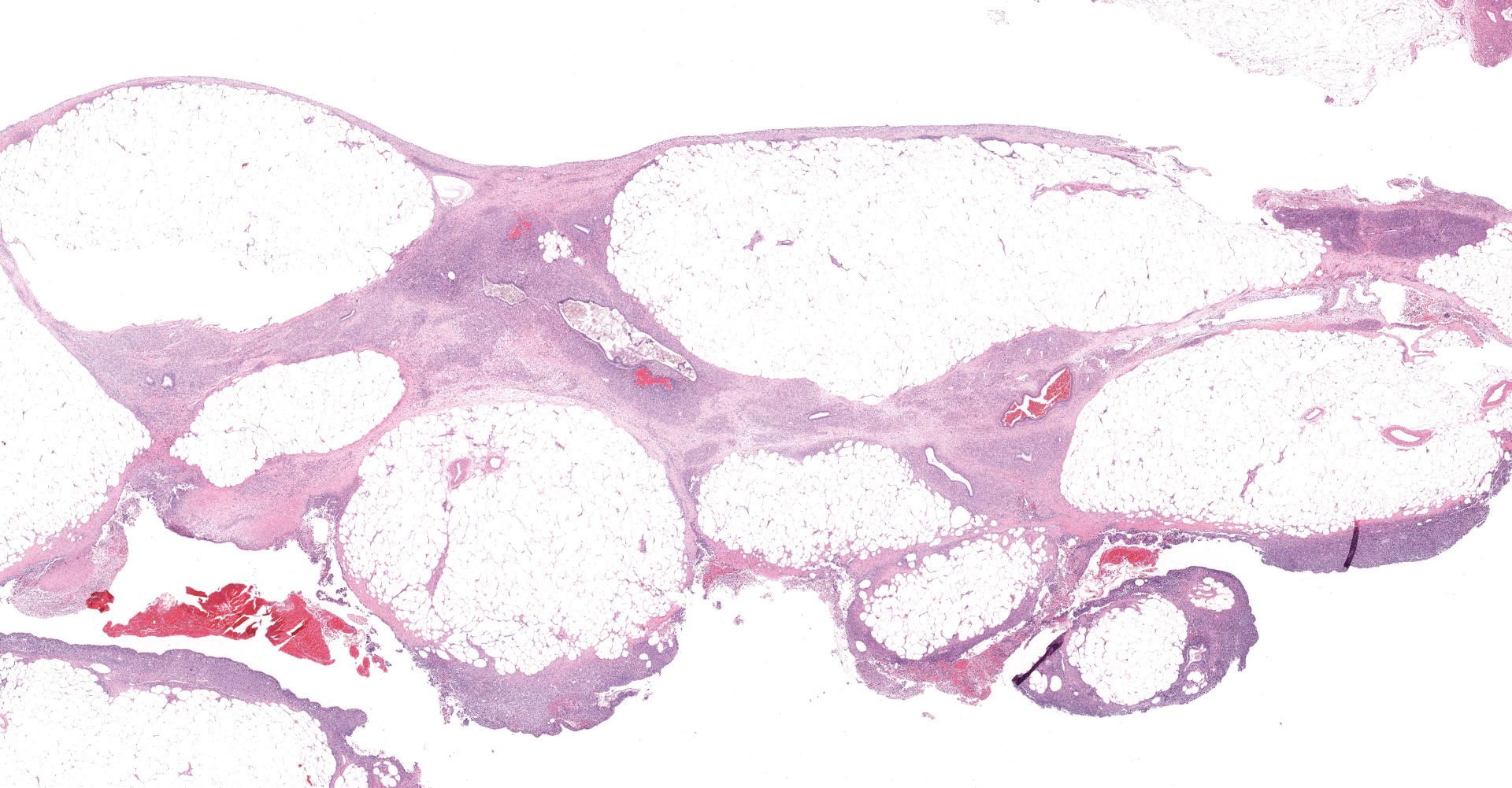

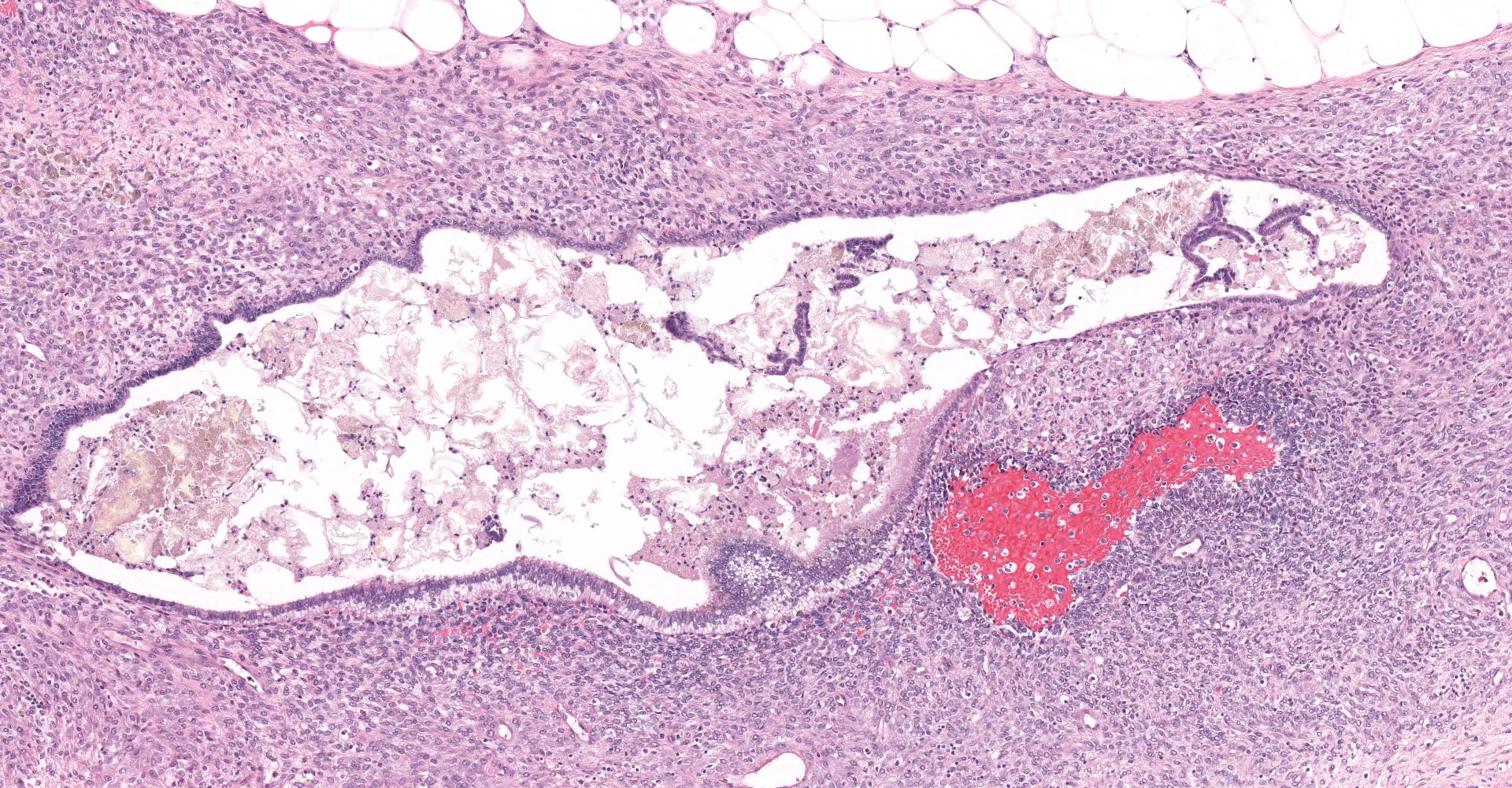

Uterus: The myometrium is multifocally thickened by hyperplastic islands and focal aggregates of papillary fronds of endometrial glands and stromal elements (adenomyosis), which disrupt and replace smooth muscle bundles. Occasionally similar findings extend to the perimetrium and adjacent mesentery (endometriosis). Lumina of endometrial glands occasionally are ectatic containing variable amounts of eosinophilic homogenous material (secretory product) admixed with cellular debris and moderate numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. The myometrium occasionally contains dense aggregates of pigment laden histiocytes interpreted to represent hemosiderin (chronic hemorrhage). There are rare lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils within the uterine stroma. The uterine lumen contains low numbers of erythrocytes, eosinophilic homogenous material, and neutrophils.

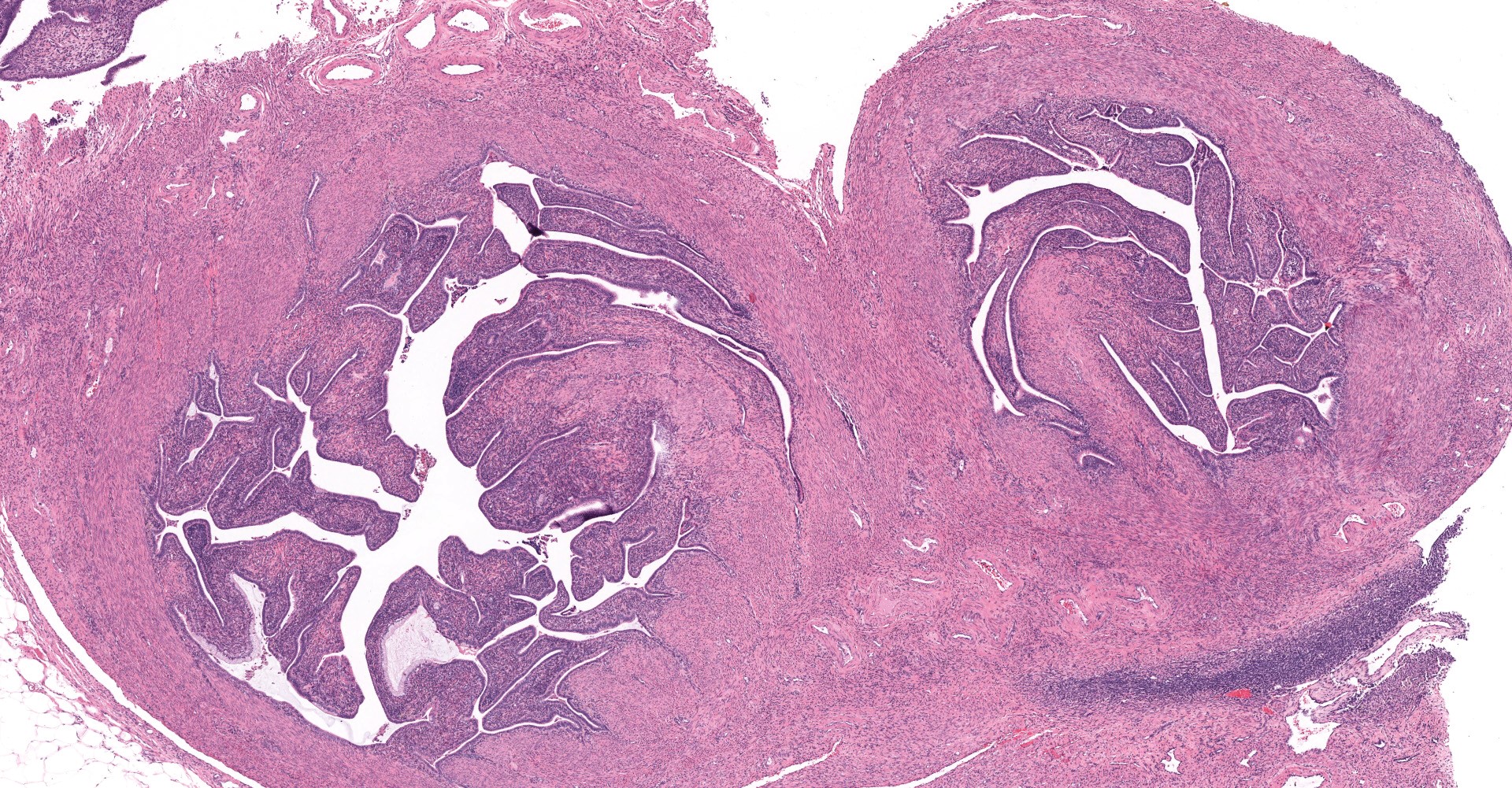

Mesentery: Expanding and effacing the mesentery are multiple, infiltrative islands of endometrial glands surrounded by abundant, densely cellular endometrial stroma. The endometrial glands are lined by simple to pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells with a moderate amount of clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent basilar vacuolation. Nuclei are anti-basilar and oval with finely stippled chromatin. Occasionally, glands contain moderate numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, erythrocytes, and exfoliated cellular debris.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

1. Uterus:

Adenomyosis and endometriosis

2. Peritoneum: Endometriosis

Contributor's Comment:

Endometriosis (endometrial glands or stroma explanted outside of the uterus-i.e., ovary, peritoneum) and adenomyosis (endometrial stroma and/or glands confined within the myometrium of the uterine wall) are non-neoplastic, estrogen-dependent, hyperplastic lesions of endometrial elements. In humans this condition has been reported to affect 10-15% of women in reproductive age, while prevalence in aged intact-female cynomologous macaques has been reported as high as 28.7%.1,7 The menstrual cycle of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) is seasonal, while that of baboons (Papio spp.) and cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascularis) is similar to humans (~4-week menstrual cycle). Accordingly, the later two are considered more relevant spontaneous models of endometriosis.

Histologic components of adenomyosis and endometriosis are heterogenous and include variable ratios of endometrial epithelium and CD10 positive stromal cells with hemorrhage and inflammation, but also smooth muscle metaplasia and nerve fibers.5,6 Gross differential diagnosis such as carcinomatosis and mesothelium are readily ruled out microscopically, given both of these conditions display features of malignancy such as cellular pleomorphism and a high mitotic index that is not observed with adenomyosis and endometriosis.

In humans, common clinical signs and or symptoms include severe dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, diarrhea and constipation and infertility.3 Fortunately in both humans and non-human primates, clinical progression is typically slow and for the most part stable over long periods of time. Complete resection of all visible foci of disease via surgery offers the best control of symptoms, however the possibility of achieving this goal both in humans and NHPs is limited by the difficulty of detecting all foci and the risks associated with radical surgical strategies, including additional seeding within laparotomy scars.8

Effective clinical screening for endometriosis in NHP colonies includes the observation of regular menstrual bleeding, serum Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels and palpation of the abdomen. Elevated serum CA125 levels are correlated with the presence of chocolate cysts in monkeys with endometriosis as well as humans.4,6 Longitudinal MRI screening in at risk populations has received recent attention as a non-invasive method both in human clinics as well as NHP breeding colonies, but is logistically and financially restrictive.9 Regardless of approaches, screening is recommended in rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys within the 11-20-year-old age group, which are at a greater frequency of menstrual bleeding and active ovarian function. Decreased food consumption has been indicated as a proposed terminal endpoint for endometriosis in NHPs knowing that this relates to severe pelvic pain and reduce quality of life.6

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Boston University Medical Campus http://www.bumc.bu.edu/busm-pathology/

JPC Diagnosis:

Oviduct, serosa and mesentery: Endometriosis with ovarian adhesion.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of endometriosis in NHPs and humans.

Interestingly, diagnosis of endometriosis remains a difficult and often lengthy process despite the prevalence of this condition in both NHP and humans. On average, women 18-45 years old with endometriosis symptoms are not diagnosed for 6.7 years.7 Clinical history, physical exam, and testing for other common causes of pelvic pain often begin the diagnostic process, followed by transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasounds and occasionally MRI and CT.7 Numerous biomarkers and assays have been evaluated as less invasive diagnostic tools, but thus far none have proven reliable.7 Diagnosis and the development of minimally invasive testing is presumably complicated by a lack of clear pathogenesis for endometriosis.

Retrograde menstruation is the most evidentially supported hypothesis, during which endometrial fragments adhere to the mesothelium and in the absence of an appropriate immune response begin to grow, bleed cyclically, and eventually cause adhesions and fibrosis.5 While this hypothesis has the most supporting evidence, additional research suggests alternative causes or contributing factors toward the development of endometriosis. This argument is partially based on the idea that retrograde menstruation is common in menstruating women, while the prevalence of endometriosis is low.7 This mismatch of prevalence leads to the idea that other factors including hormones, inflammation, and immunologic status may also play a role in its development. In the face of these barriers, biopsy and histological confirmation remain gold standard for definitive diagnosis.7

Grossly, endometriosis is described in humans and NHPs as "chocolate cysts " that are brown, reddish, black, or blueberry in color and are found to be associated with the ovaries, uterus, and sometimes the surface of other organs or the peritoneal wall. Severe abdominal adhesions are also commonly described in both human and NHP with severe endometriosis.5

The unique histomorphologic features within the submitted section generated spirited discussion amongst conference participants in regard to tissue and lesion identification. The case was subsequently referred to our colleagues within the subspecialty of (human) reproductive pathology.

Following consultation and further discussion amongst the staff, there is consensus that regions of tissue described as adenomyosis are more consistent with oviduct and adhered atypical ovarian tissue.

References:

1. Ami Y, Suzaki Y, Goto N. Endometriosis in cynomolgus monkeys retired from breeding. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55: 7-11.

2. Cline JM, Wood CE, Vidal JD, et al. Selected Background Findings and Interpretation of Common Lesions in the Female Reproductive System in Macaques. Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36(7):142s-163s.

3. Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91: 32-39.

4. Muyldermans M, Cornillie FJ, Koninckx PR. CA125 and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1995;1: 173-187.

5. Nishimoto-Kakiuchi A, Netsu S, Matsuo S, et al. Characteristics of histologically confirmed endometriosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Hum Reprod. 2016;31: 2352-2359.

6. Nishimoto-Kakiuchi A, Netsu S, Okabayashi S, et al. Spontaneous endometriosis in cynomolgus monkeys as a clinically relevant experimental model. Hum Reprod. 2018;33: 1228-1236.

7. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6: 34-41.

8. Rimbach S, Ulrich U, Schweppe KW. Surgical Therapy of Endometriosis: Challenges and Controversies. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013;73: 918-923.

9. Takahashi N, Yoshino O, Maeda E, et al. Usefulness of T2 star-weighted imaging in ovarian cysts and tumors. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42: 1336-1342.