Signalment:

Gross Description:

The ventral pylorus was adhered to the left ventral abdominal wall by bands of dense, tan fibrous tissue. The liver was firm with irregular, rounded margins and contained approximately 10-12, 0.2 cm to 3.5 cm diameter, fluid-filled cysts (suspect biliary cysts). The gall bladder was moderately enlarged and contained variably-sized clumps of dark green, inspissated bile. The pancreas was atrophied, pale, firm, and nodular. The mucosa of both the small and large intestines was moderately thickened and the jejunum was corrugated. The kidneys contained multiple cysts that were approximately 0.2 cm in diameter and contained clear fluid. These cysts were present throughout the parenchyma and along the capsular surface. Multiple pale, tan, round, 0.5 mm diameter foci were scattered regularly throughout the cortical tissue.Â

Five to ten milliliters of clear, serosanguineous fluid were in the pleural space. The lungs were markedly congested and oozed blood on cut surface. The heart was rounded and the septal leaflets of the mitral valve were moderately thickened by smooth, variably-sized nodules (nodular endocardiosis).

Histopathologic Description:

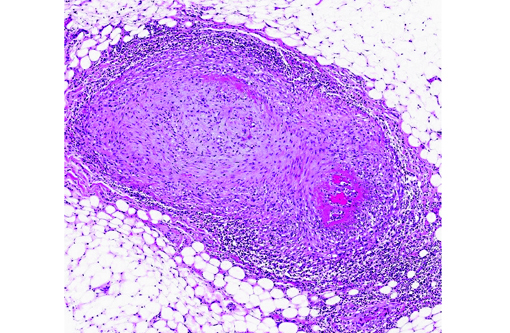

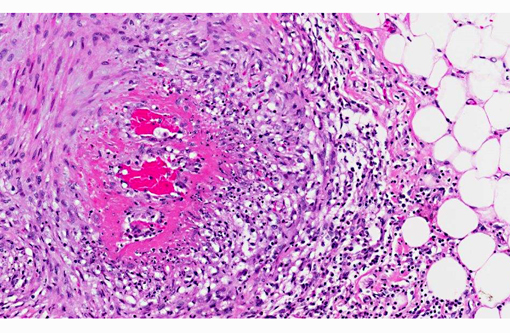

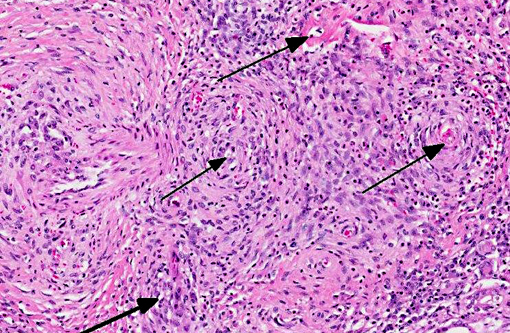

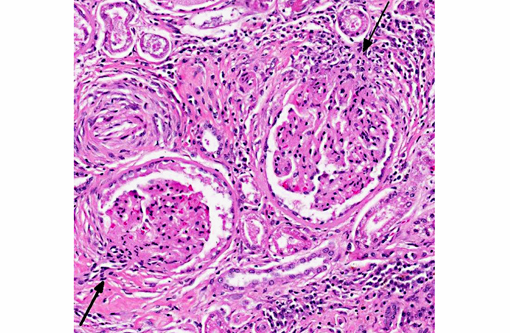

The walls of arteries throughout the kidney and perirenal fat were markedly expanded by hypertrophied smooth myocytes, fibrosis, and infiltrating neutrophils and lymphocytes, leading to the obstruction of the vascular lumens (as described above). Affected vessels were surrounded by moderate, streaming fibrosis. Moderate to marked interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates were scattered throughout the renal parenchyma. Bowman's capsule was moderately expanded in the majority of the glomeruli, as was the mesangium of several glomerular tufts. Glomerular tufts occasionally adhered to the capsule (synechia). Multifocally, the tubular epithelium was variably swollen, vacuolated or attenuated, and hypereosinophilic, suggestive of early epithelial degeneration. Occasional tubules were dilated and contained glassy, amorphous, lightly eosinophilic material. A few, scattered tubules were markedly dilated by a flocculent, eosinophilic material. In both kidneys, the connective tissues around the renal pelvises were moderately to markedly infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Within the heart, the coronary arteries and vessels in the pericardial fat were multifocally, markedly affected by the vascular changes described above. Multifocally, the myocardium was mildly infiltrated by mature fat. In one section of myocardium, the myofibers were mildly separated by a fine fibrous connective tissue.

The lobules within the pancreas were moderately to markedly separated by dense fibrosis, which occasionally invaded into the lobules, isolating small islands of acini. Multifocal, mild aggregates of lymphocytes were apparent within the fibrosis. Multifocal vessels in the pancreatic parenchyma and the adjacent mesentery were effaced by the previously described inflammatory process (pancreas not submitted).Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney:

- Moderate, global, diffuse membranoproliferative glomerulopathy

- Multifocal, moderate lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis

- Acute tubular degeneration and multifocal tubular proteinosis

Heart:

- Mild, multifocal fatty infiltration

- Focal, mild myocardial fibrosis

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Vasculitis is defined as the invasion of vessel walls by inflammatory cells with associated vascular damage, which can include fibrin deposition, collagen degeneration, and necrosis.(5,6) In animals and humans, vasculitis can be categorized as immune-mediated, infectious, toxic, hemodynamic-mediated, or idiopathic.(1,4,5) Infectious causes of vasculitis in dogs include canine distemper virus, bacterial septicemia and endotoxemia, rickettsial organisms, mycotic infections, protozoal organisms, and rarely helminths.(5) In this patient, infectious causes were considered unlikely based on the lack of an organism seen histologically, the negative peritoneal culture, and the lack of any other histologic or gross features associated with an infectious organism.

Immune-mediated vasculitis is a differential diagnosis for the vascular changes in this dog, though such immune-mediated reactions are less common in dogs than in humans.(1,5) The main pathologic processes that can lead to immune-mediated vasculitis include antibody/antigen complex deposition secondary to an infection or a hypersensitivity response, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, or anti-endothelial cell antibodies.(4) One type of vasculitis that is thought to be immune-mediated is polyarteritis nodosa. Polyarteritis nodosa is rarely described in dogs and is considered to be similar to idiopathic juvenile polyarteritis (discussed below). This condition is characterized by segmental, necrotizing vasculitis of small to medium sized arteries. Arterioles, capillaries, and venules are typically not involved, and glomerulonephritis is not present.(5) Type IV hypersensitivity-associated vasculitis is also an immune-mediated vasculitis that has also been described as affecting small vessels (though sparing muscular arteries) and is characterized by a non-necrotizing, mononuclear vasculitis.1 Hypersensitivity vasculitides commonly occur in the skin, and have been associated with systemic lupus erythematosis in dogs.(3,5) Drug reactions occasionally cause type III hypersensitivities, which result from the deposition of antibody/antigen complexes within small vessels, leading to a necrotizing vasculitis.(5) The skin was not examined histologically in this dog.

Toxic damage to the endothelium or to the vascular smooth muscle cells caused by medications has been reported to lead to a necrotizing vasculitis. This form of vasculitis affects small to medium arteries in multiple organs, and is characterized by transmural segmental fibrinoid necrosis and neutrophilic inflammation, which also affects surrounding tissues. Focal medial scarring and adventitial fibrosis has also been described.(1) Toxic vasculitis is difficult to differentiate from polyarteritis nodosa. Medications can also lead to vascular damage caused by excessive hemodynamic activity. For example, dogs have been reported to be sensitive to vasodilators and positive inotropes, and develop vascular lesions associated with their use. The acute histologic features of this lesion include segmental medial necrosis and hemorrhage of the coronary arteries. Chronic changes include smooth muscle hyperplasia of the intima and adventitial fibroplasia, and medial degeneration, necrosis, and variable inflammation.(1) There was no history of vasodilator or positive inotrope use in this dog.

In most cases of vasculitis in dogs, the cause is unknown. Some idiopathic vasculitides appear to occur more commonly in certain breeds. For example, several authors have described a juvenile polyarteritis in beagle dogs.(1,2,5,8,9) This syndrome occurred primarily in young beagle dogs (<40 months of age). These dogs developed sudden-onset fever, anorexia, and a hunched stance that waxed and waned. However, in one study, affected beagles did not show any clinical signs.(9) Histologically, acutely affected small to medium-sized muscular arteries were characterized by necrotizing vasculitis with occasional fibrinoid change and perivascular nodules predominately composed of neutrophils with multifocal accumulations of macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Affected organs included the extramural coronary arteries, cervical spinal cord, and the cranial mediastinum. Less commonly affected organs included thyroid glands, thymus, lymph nodes, stomach, small intestine, esophagus, urinary bladder, epididymis, gall bladder, lung, and diaphragm. Few dogs exhibit severe, diffuse, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.(8,9) Hemorrhage and necrosis were not associated with the vascular lesions in these studies.(1)

In this case of necrotizing polyarteritis, beagle pain syndrome was considered unlikely due to the age of the patient. Additionally, based on the histologic features described above, including the presence of necrotizing vasculitis in multiple organs, the minimal associated necrosis and hemorrhage, and the restriction of the lesions to the small and medium muscular arteries, type IV hypersensitivity reactions were considered less likely. These lesions typically spare muscular arteries, typically occur in the skin, and generally do not have associated fibrinoid necrosis. Vasculitis secondary to excessive hemodynamic activity was also unlikely, because these lesions are often restricted to coronary arteries, and are less likely to have associated inflammation. Interestingly, this dog had a history of chronic pancreatitis, which may have caused or at least contributed to the vasculitis and the glomerulopathy through the production of circulating antigen/ antibody complexes. As a result, a toxic vasculitis, an immune-mediated vasculitis, or an idiopathic vasculitis remain the most likely differentials for this patient.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney, heart and adjacent vessels: Arteritis, necrotizing and proliferative, chronic, diffuse, severe with fibrinoid change.

2. Kidney: Glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative, diffuse, moderate, with multifocal tubular necrosis and lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis.

Conference Comment:

Type I, or immediate type hypersensitivity reactions involve an initial sensitization phase to an allergen or parasite, as well as an effector phase upon secondary or prolonged initial exposure, mediated by IgE antibody cross-linking, mast cell degranulation (resulting in release of vasoactive amines and other mediators) and, in late phase reactions, recruitment of inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils. Type I hypersensitivity is associated with anaphylaxis, and is characterized by increased vascular permeability (edema) and dilation (hypotension), smooth muscle contraction (bronchospasm), mucus production and inflammation. Interestingly, the guinea pig is the species most sensitive to the development of anaphylaxis.Â

Type II, or cytotoxic hypersensitivity reactions occur following the development of antibodies against cell surface antigens or receptors, with subsequent phagocytosis or lysis of the target cell by activated complement or Fc receptors, as well as recruitment of leukocytes. Due to the presence of numerous blood group surface antigens and a predilection for absorbing drugs and antigens associated with infectious agents or tumors, erythrocytes are particularly prone to this type of antibody-mediated hypersensitivity reaction (e.g. autoimmune hemolytic anemia and foal neonatal isoerythrolysis). Furthermore, antibodies directed against cell surface receptors can either activate or inhibit cell function. For instance, binding of antibody to the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor activates thyroid follicular epithelial cells, resulting in hyperthyroidism, while antibody binding the acetylcholine neurotransmitter receptor at the neuromuscular junction inhibits cell function, resulting in myasthenia gravis.(7)

Type III hypersensitivity reactions, as noted by the contributor, can incite necrotizing vasculitis via formation and deposition of antigen-antibody complexes which lead to complement activation, recruitment of leukocytes, release of free radicals, proteolytic enzymes and other toxic molecules. In order for deposition of antigen-antibody complexes to occur, there must be a slight antigen excess with the formation of intermediate sized complexes; deposition tends to occur at sites where blood is filtered at high pressure, such as glomeruli, joints, small vessels, the heart, the skin, or the serosa. Examples include systemic lupus erythematosus, equine infectious anemia and acute glomerulonephritis.(9)

Type IV hypersensitivity reactions, also known as cell mediated or delayed-type, are mediated by CD4+ or CD8+ T-lymphocytes (see WSC 2013-2014, conference 2, case 2 for a review of CD4+ T-lymphocyte mediated hypersensitivity). CD8+ T-lymphocytes are activated by antigen expressed in the context of MHCI and are directly cytotoxic to target cells via granzyme A/perforin (which leads to caspase-independent apoptosis), granzyme B (leading to caspase-dependent apoptosis) or Fas:Fas ligand interactions (which induces extrinsic apoptosis). Tuberculosis, Johnes disease, allograft rejection and allergic contact dermatitis are all diseases associated with primary type IV hypersensitivity reactions.(7)

Table 1. Mechanisms of Immunologically Mediated Hypersensitivity Reactions.(7)

| Type | Prototype Disorder | Immune Mechanisms | Pathologic Lesions |

| Type I (immediate) hypersensitivity | Anaphylaxis; allergies; bronchial asthma | Cross linking of IgE antibody, mast cell degranulation â release of vasoactive amines and other mediators; recruitment of inflammatory cells (late-phase reaction) | Vascular dilation, edema, smooth muscle contraction, mucus production, inflammation |

| Type II (antibody-mediated/ cytotoxic) hypersensitivity | Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; neonatal isoerythrolysis | Production of IgG, IgM â binds to antigen on target cell or tissue â phagocytosis or lysis of target cell by activated complement or Fc receptors; recruitment of leukocytes | Cell lysis; inflammation |

| Type III (immune complex- mediated) hypersensitivity | Systemic lupus erythematosus; glomerulonephritis; serum sickness; Arthus reaction | Deposition of antigen-antibody complexes â complement activation â recruitment of leukocytes â release of enzymes and other toxic molecules | Necrotizing vasculitis (fibrinoid necrosis); inflammation |

| Type IV (cell-mediated/delayed-type) hypersensitivity | Contact dermatitis; transplant rejection; tuberculosis; Johnes disease | Activated T lymphocytes: 1. Release of cytokines and macrophage activation 2. T cell-mediated cytotoxicity | Perivascular cellular infiltrates; edema; cell destruction; granuloma formation |

References:

1. Clemo FAS, Evering WE, Snyder PW, Albassam MA. Differentiating spontaneous from drug-induced vascular injury in the dog. Toxicol Pathol. 2003;31(Suppl.):25-31.

2. Hayes TJ, Roberts GK, Halliwell WH. An idiopathic febrile necrotizing arteritis syndrome in the dog: beagle pain syndrome. Toxicol Pathol. 1989;17(2):129-137.

3. Hoff E J, Vandevelde M. Case report: necrotizing vasculitis in the central nervous systems of two dogs. Vet Pathol. 1981;18:219.

4. Maxie MG, Robinson WF. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007:1-103.

5. Mitchell RN, Schoen FJ. Blood vessels. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2010:487-528.Â

6. Nichols PR, Morris DO, Beale KM. A retrospective study of canine and feline cutaneous vasculitis. Vet Dermatol. 2001;12:255-264.

7. Snyder PW. Diseases of immunity. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:258-270.

8. Snyder PW, Kazacos EA, Scott-Moncrieff JC, et al. Pathologic features of naturally occurring juvenile polyarteritis in beagle dogs. Vet Pathol. 1995;32(4):337-345.

9. Son W. Idiopathic canine polyarteritis in control beagle dogs from toxicity studies. J Vet Sci. 2004;5(2):147-150.