Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 2

August 30th, 2017

CASE II: 1235813-002 (JPC 4101299).

Signalment: Juvenile female cynomolgus macaque, non-human primate (Macaca fascicularis).

History: This animal had decreased body weight, and a history of soft watery feces. It was found hypothermic and lying on floor of the cage and was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology: No gross pathology lesions were observed.

Laboratory results: None provided.

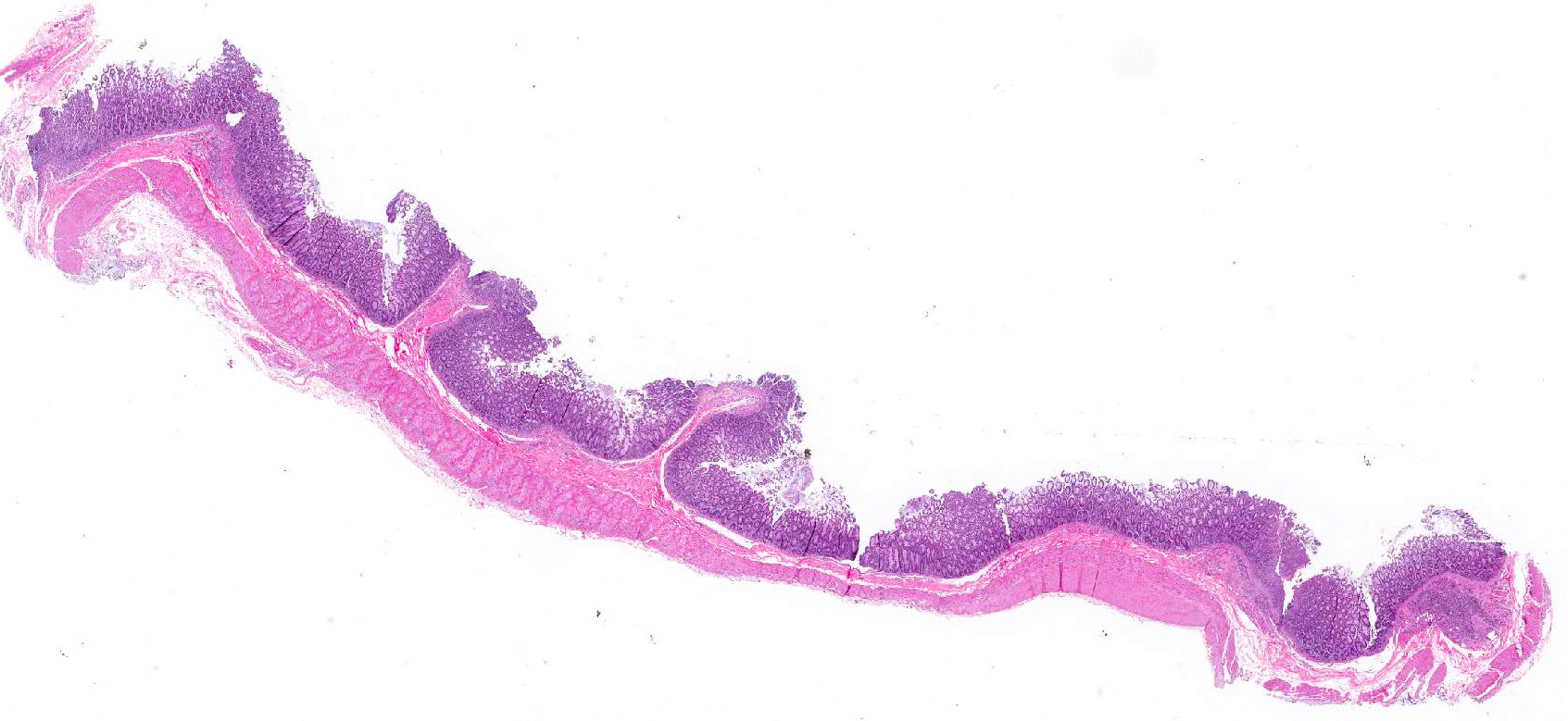

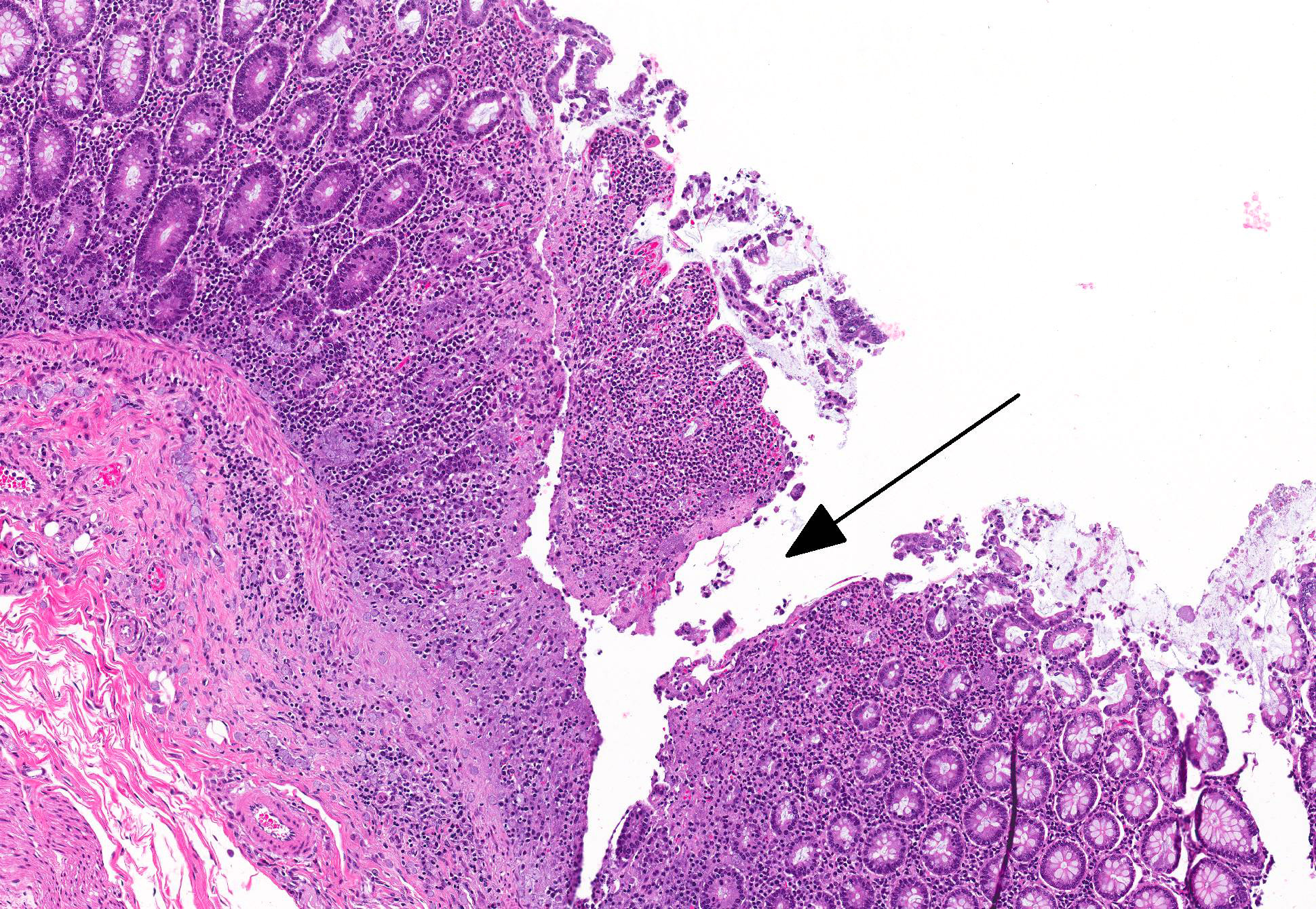

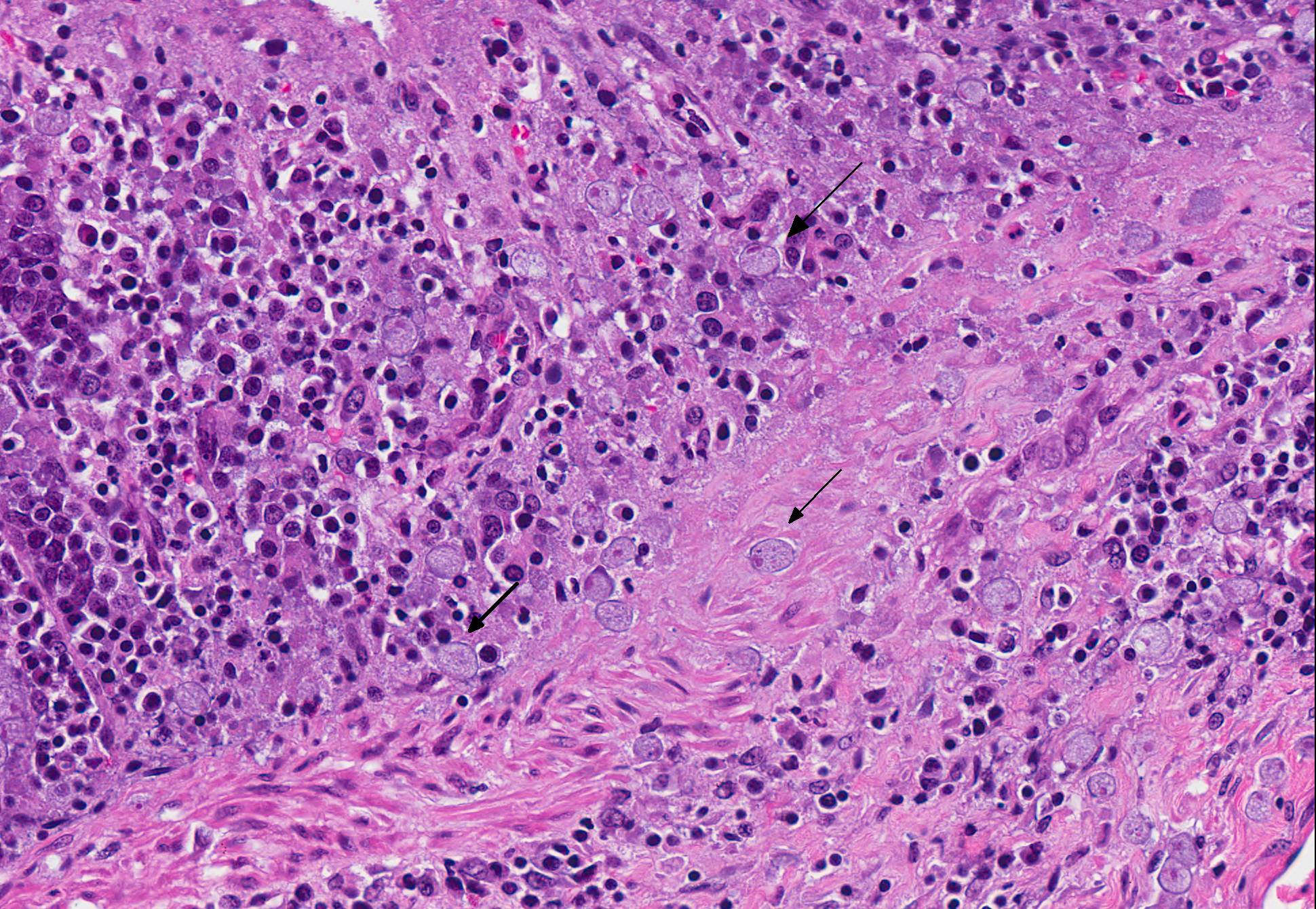

Microscopic Description: Colon: There are multifocal areas of segmental to full-thickness loss of mucosal architecture, with colonic crypts replaced by pale staining eosinophilia with pyknotic and karyorrhectic nuclear debris (necrosis) and some viable neutrophils. Crypts adjacent to the necrotic areas are variably lined by detached epithelial cells with pyknotic nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Frequently scattered within the areas of necrosis, as well as within the submucosa, there are clusters of round protozoal trophozoites, which partially efface occasional crypts. Clusters of bacterial colonies are noted within the superficial to mid-mucosa in some areas of necrosis. The colonic lamina propria is infiltrated by a mixed population of inflammatory cells, including moderate numbers of plasma cells, fewer lymphocytes, and rare eosinophils. In some slides, the colonic serosa is infiltrated by a similar inflammatory cell population.

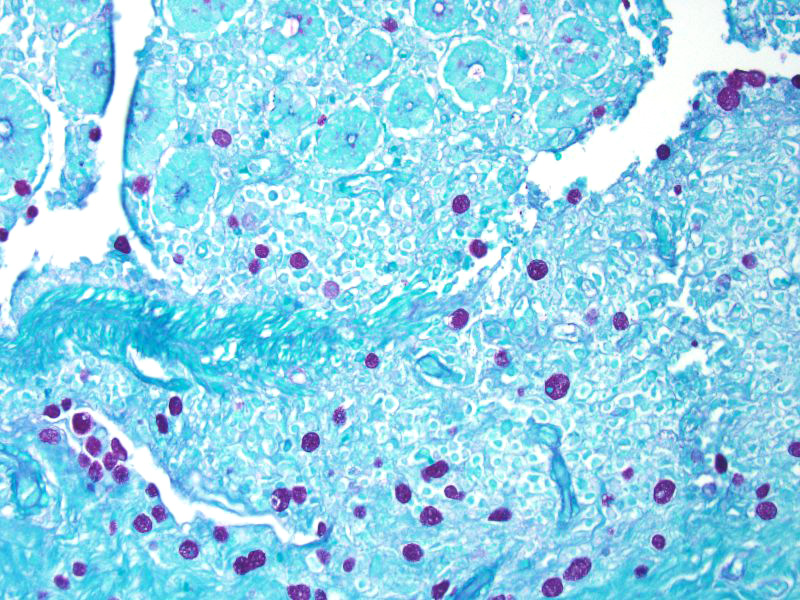

Some sections of colon contain gut-associated lymphoid tissue with loss of lymphocytes and variable necrosis. The protozoa stained positive with PAS and the bacteria were identified as a mixture of gram negative and gram positive organisms with a Gram Twort stain.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis: Colon: Acute, multifocal, necrotizing colitis, with intralesional protozoa consistent with Entamoeba histolytica.

Contributors Comment: Non-human primates held in laboratory and research settings harbor a variety of intestinal parasites that rarely cause clinical infection.5 Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite that is a part of the normal fauna, but has also been shown to be pathogenic in captive non-human primates. Amebiasis affects the colon, causing diarrhea and can also cause liver abscesses, and ultimately lead to death.1 It is of particular concern because of its zoonotic potential.3 Clinical disease secondary to this pathogen is uncommon in the biomedical research laboratory setting and is usually secondary to stress or immunosuppression.

Definitive speciation of Entamoeba spp. can be made using PCR-reverse line hybridization blot (RLHB), as differentiation of this protozoan from Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba nutalli, and other species of this genera using light microscopy can be challenging.1,3 Because of this difficulty, it has been suggested to make a combined diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar unless molecular differentiation can be made. Entamoeba nutalli was found to be pathogenic in in Japanese macaques in a study where Entamoeba dispar was not identified, despite being reported to be prevalent in captive macaques. This suggests that colonies of macaques in captivity may have differing predominant causes of amebiasis.2

A definitive diagnosis of intestinal amebiasis may be complicated in cases of macaques infected with Entamoeba chattoni, as it has been shown to breach the mucosa of the cecum shortly after death.4 In the case presented here, protozoal trophozoites are present in the submucosa with and without any associated pathology in varying areas of the slide. However, the organisms present within the mucosa and the GALT (present in some slides) are associated with pathology.

JPC Diagnosis: Colon: Colitis, necrotizing, multifocal, moderate with numerous amoebic trophozoites, cynomolgus macaque, non-human primate (Macaca fascicularis).

Conference Comment: Conference participants discussed two species of Entamoeba: E. histolytica and E. dispar (the primary form of amoeba found in macaques).4 Amoebic dysentery caused by Entamoeba histolytica is relatively common in humans and nonhuman primates, but rarely infects other species. Cats are susceptible to experimental infection, and infection in dogs is sporadic and most likely caused by ingestion of infected human feces. Dogs act as dead end hosts since they dont pass encysted amebae, and thus present little public health hazard.

Amebae are usually nonpathogenic organisms that inhabit the lumen of the large intestine, but may cause colitis due to changes in host diet or immune status, or the virulence attributes of the organism. Additionally, disease appears to be more common in animals with concurrent Trichuris or Ancylostoma infections.

The essential steps leading to tissue damage by amebae are: adhesion to mucus by lectins, enzymatic breakdown of protective mucus, and lectin-mediatedadherence to host epithelium. E. histolytica releases cysteine proteases that cause damage to mucosal epithelium and attract inflammatory cells, both of which lead to characteristic ulcerative colitis with flask shaped ulcers. Microscopically, amebae are surrounded by a clear halo with extensive pseudopodia and possess a nucleus with a dark karyosome. The cytoplasmappears foamy and they frequently phagocytize erythrocytes, which makes them difficult to distinguish from activated macrophages.7 A periodic acid-Schiff stain was viewed during the conference which nicely highlighted intracytoplasmic glycogen granules within amebae; it also lightly stained goblet cells within the mucosa. Trichrome and Giemsa stains can also be used to highlight amoebic trophozoites. Due to the presence of intracytoplasmic glycogen (starch), Lugols iodine can also be used to diagnose the presence of trophozoites via direct smear.

In humans and non-human primates, primary sites of dissemination are the liver (through the portal circulation) and less commonly, lung and brain. Fatal amebiasis with abscess formation has been reported in various primate species.5 Recent reports in transgenic mice that overexpress Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic gene) reveal that epithelial cell apoptosis facilitates E. histolytica infection in the intestinal tract.1

Conference participants discussed several ruleouts including: Shigella flexneri and S. sonnei (both are gram-negative bacilli that cause necrohemorrhagic colitis and can lead to submucosal ulceration and perforation), Salmonella enteritidis and S. typhimurium (which, although less common, cause necrotizing suppurative enterocolitis with paratyphoid nodule formation and can lead to septicemia with pyogranulomas in other organs), Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli (these are spiral bacteria evident with silver stains, and the most frequently isolated enteric pathogens causing mild colonic mucosal hyperplasia), Yersinia enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis (large colonies of gram-negative bacteria within necroulcerative enterocolitis), and Balantidium coli (ciliated trophozoites with a kidney-shaped macronucleus, can cause ulcerative enterocolitis which is fatal in great apes).5 Leaf-eating primates (colobus monkey, silver-leafed monkey) are particularly susceptible to erosive and ulcerative gastritis due to a higher gastric pH (similar to the colon in other species) which is conductive to the survival of the amebae.5 Comparatively, Entamoeba invadens was discussed as causing significant disease in snakes. E. invadens is typically spread via fecal-oral transmission and results in hemorrhagic enteritis and colitis, with subsequent spread to the liver via portal circulation to cause hepatic abscesses.2

Lastly, free-living (leptomyxid) amoebae were reviewed, which rarely cause disease, but may in immunosuppressed animals. Acanthamoeba sp., Balamuthia mandrillaris and Naegleria fowleri may result encephalitis. Acanthamoeba sp. and B. mandrillaris both cause granulomatous amoebic encephalitis. In contrast, N. fowleri infection is such an acute process that there are very few inflammatory cells associated with infection.5

Contributing Institution:

http://www.mpiresearch.com

References:

- Becker SM, Cho KN, Guo X, et al. Epithelial cell apoptosis facilitates Entamoeba histolytica infection in the gut. Am J Pathol. 2010; 176(3):1316-1322.doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090740.

- Flanagan JP. Chelonians (turtles, tortoises). In: Miller RE, Fowler ME, eds. Fowlers Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. Vol. 8. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:70.

- Levecke B, Dreesen L, Dorny P, Verweij J, Vercammen F, Casaert S, Vercruysse J, Geldhof P. Molecular identification of Entamoeba spp. in captive nonhuman primates. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(8):2988-2990.

- Purcell JE, Philipp MT. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Wolfe-Coote S, ed. The Handbook of Experimental Animals the Laboratory Primate. 1st ed. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2005:581-582.

- Strait K, Else JG, Eberhard ML. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, ed. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. Vol 2. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2012:206-209, 221-222, 599-602.

- Tachibana H, Yanagi T, Akatsuka A, Kobayashi S, Kanbara H, Tsutsumi V. Isolation and characterization of a potentially virulent species of Entamoeba nutalli from captive Japanese macaques. Parasitology. 2009;136:1169-1177.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:242.

- Verweij J, Vermeer J, Brienen A. Entamoeba histolytica infections in captive primates. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:100-103.

- Vogel P, Zaucha G, Goodwin Sm Kuel K, Fritz D. Rapid postmortem invasion of cecal mucosa of macaques by nonpathogenic Entamoeba chattoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(6):595-602.

- Zanzani S, Gazzonix A, Epis S, Manfredi M. Study of the gastrointestinal parasitic fauna of captive non-human primates (Macaca fascicularis). Parasitol Res. 2016;115:307-312.