Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 12, Case 1

Signalment:

Stillborn male rocky mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) lamb, estimated gestational age of greater than 140 daysHistory:

Gross Pathology: Crown-rump length was 48.5 cm. No obvious gross abnormalities were seen within the examined organs.Laboratory Results:

Neospora and Toxoplasma Duplex PCR on paraffin-embedded brain tissue: Toxoplasma detected, Neospora not detected.Microscopic Description:

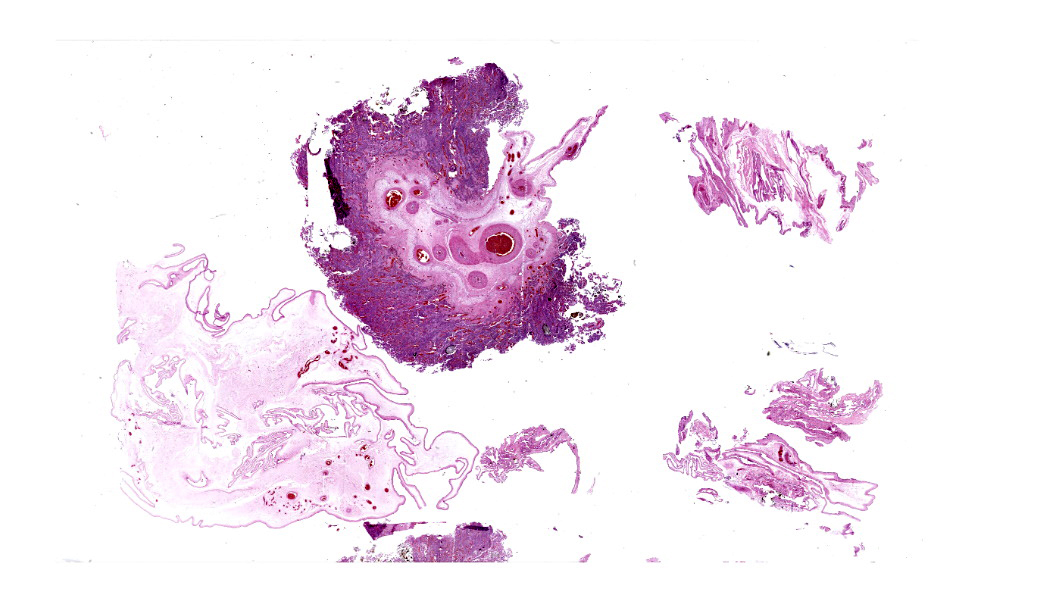

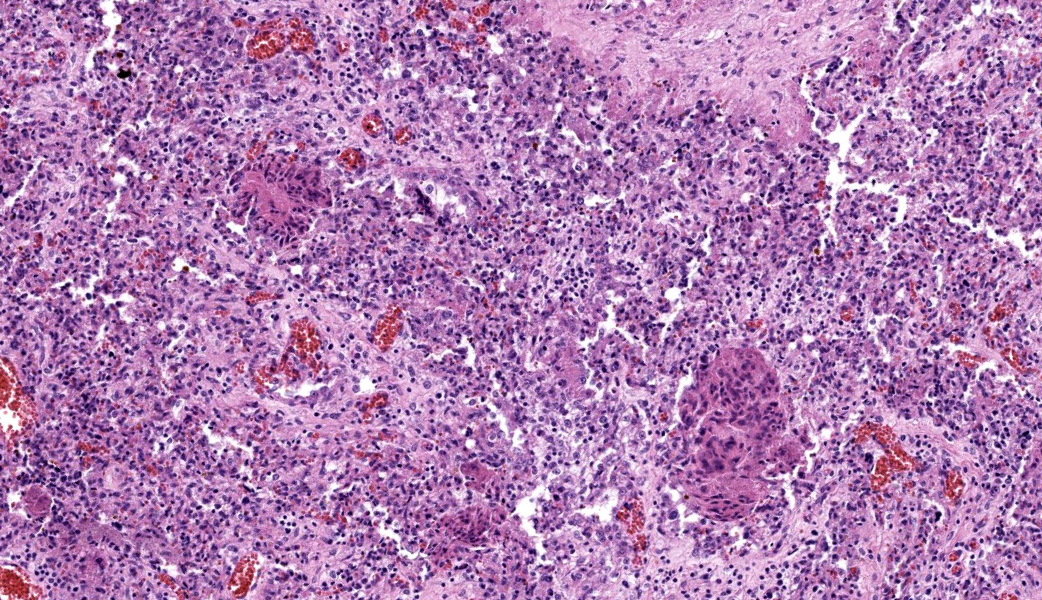

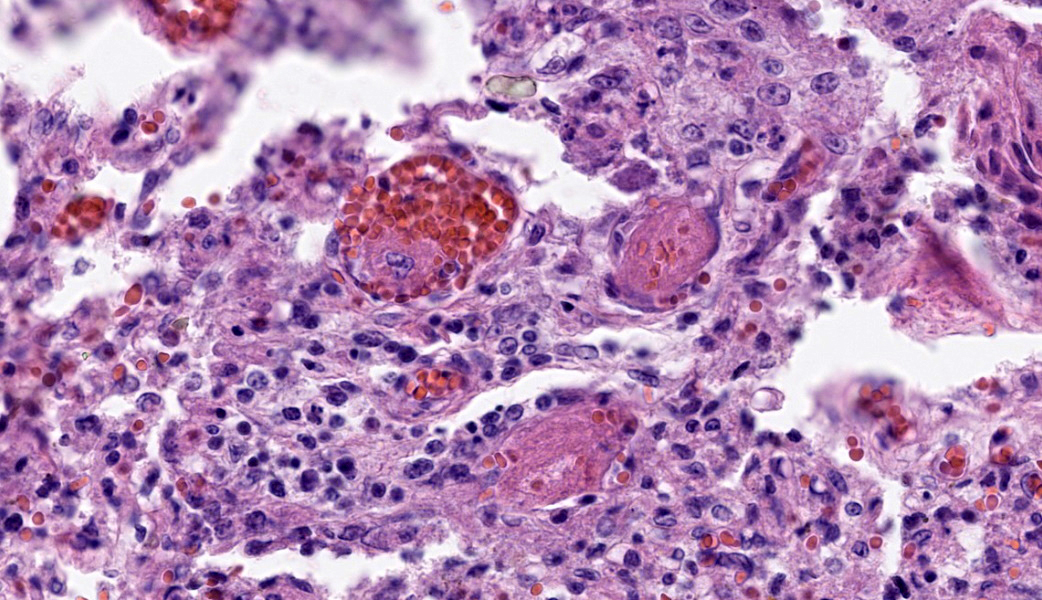

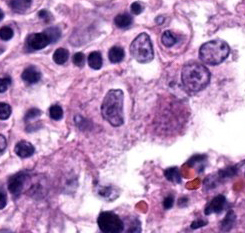

Placenta: Trophoblasts are rarely expanded by single intracytoplasmic protozoal cysts up to 15 μm in diameter with thin, refractile, bright eosinophilic walls which surround dozens of elongate 2 x 1 μm bradyzoites. Multiple regions within the cotyledonary placenta comprising approximately 15% of the total examined area are effaced by hypereosinophilic cellular and pyknotic to karyorrhectic nuclear debris (lytic necrosis) and fibrillar to amorphous eosinophilic material (fibrin). Small caliber blood vessels within the cotyledonary placenta are occasionally occluded by dense fibrin coagula with loss of the subjacent endothelium (fibrin thrombi).Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Placentitis, necrotizing, acute, multifocal, moderate with thrombosis and intralesional protozoal cysts morphologically consistent with Toxoplasma gondii.Contributor's Comment:

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasitic protozoan in the phylum Apicomplexa, and the cause of toxoplasmosis. Members of the Felidae family are definitive hosts of T. gondii. Following infection through ingestion of tissues containing T. gondii cysts, felids typically shed oocysts in their feces for one to two weeks. All other homeothermic vertebrate species are susceptible to infection and become intermediate hosts through ingestion of food, water, or soil contaminated with oocysts. Following ingestion, sporozoites are released from the oocyst and multiply asexually within the intestinal lamina propria as tachyzoites. Within hours, tachyzoites disseminate hematogenously or via lymphatics to other organs. T. gondii forms tissue cysts within the organs of intermediate hosts, with muscular and neural tissues preferentially affected. Tissue cysts persist for the life of the host and will perpetuate the life cycle if ingested by a felid.3The outcome of infection is dependent upon individual host and parasite factors, including host susceptibility, immune status, parasite virulence, and parasitic life stage to which the host is exposed. Infected animals may remain subclinical or progress to systemic infection, abortion, and/or death.5 Spread of tachyzoites to the placenta and fetus of a pregnant animal typically results in necrotizing lesions within the placenta and fetal brain, though other organs may also be involved.2 In this case, protozoal cysts associated with mononuclear inflammation were also identified within the brain, lungs, and adipose tissue. Toxoplasmosis and neosporosis can cause similar lesions, and the tissue cysts of each species cannot be reliably distinguished using histology alone. Therefore, definitive diagnosis relies on ancillary testing such as PCR or immunohistochemistry.6

The reproductive consequences of T. gondii infection are well-studied in domestic sheep, with one meta-analysis reporting detection of T. gondii using molecular methods in 42% of aborted sheep fetuses from 11 countries.7 However, its impact on wild sheep populations is poorly understood. Only one case of confirmed toxoplasmosis in a bighorn sheep has been published to date.1Contributing Institution:

Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, Washington State University (https://waddl.vetmed.wsu.edu/)JPC Diagnoses:

Placenta: Placentitis, necrotizing, subacute, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with intratrophoblastic and intrahistiocytic apicomplexan zoites.JPC Comment:

This year’s 12th conference was moderated by the JPC’s own MAJ Anna-Maria Travis, an enthusiast of reproductive pathology, who led participants through a “Call the Midwife”-themed conference, complete with a fancy English tea party. As participants donned bowties and/or fasteners, sipped hot tea out of fine bone china, and enjoyed scones with homemade clotted cream, this first case demonstrated a classic entity that is an absolute “must-know” for any diagnostic pathologist.The contributor’s comment gives a great overview of the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii, which participants were asked to recount during conference. In many species, Toxoplasma gondii is known to cause disseminated disease, infections of the CNS (leukoencephalomalacia), and abortions (except in cattle). It is considered an economically important cause of abortions in sheep and goats, especially in late pregnancy, and generally results in classic gross lesions in the placental cotyledons. Affected cotyledons are bright red (in contrast to their normal deep purple color) and contain numerous 1-3mm white flecks/foci of necrosis and mineralization. The intercotyledonary chorioallantois is usually spared but may be edematous.

Fetal leukoencephalomalacia has been reported in fetal lambs infected with Toxoplasma gondii.4 In fetuses with leukomalacia, histologic loss of oligodendrocytes and increased numbers of both astrocytes and microglia in areas of necrosis and the immediately-surrounding neuropil are common findings.4 These lesions are similar to those seen in sheep used experimentally for inflammation syndrome and hypoxic models of periventricular leukomalacia in humans. It has been hypothesized that a fetal inflammatory syndrome resulting in hypoxia of the CNS may be involved in the pathogenesis of early abortion in ovine toxoplasmosis.4

Ewes do not typically show any signs of infection, and the effects on the fetus depend on the stage of gestation. In early gestation, fetal death with resorption or mummification is common. In mid-gestation, there can either be fetal death with resorption/mummification or there may be stillborn lambs. Occasionally, a fetus infected during this time frame may survive to term, but they are usually weak and do not survive long. In late gestation, the fetus will develop an immune response and may survive.

Important differentials to consider in ovine placentitis were included in conference discussion and covered: Neospora caninum, which causes similar lesions in the aborted placenta to T. gondii and requires PCR to differentiate; Chlamydia abortus, which causes a necrotizing placentitis with vasculitis that, in contrast to T. gondii, will affect the intercotyledonary areas and produce a leathery thickening of the placenta; Coxiella burnetti, which will cause similar lesions to Chlamydia abortus, but without vasculitis; Brucella ovis, which produces a thick, brown exudate that covers the chorionic surface of the placenta, causes leathery thickening of the intercotyledonary spaces, and is associated with vasculitis; Campylobacter fetus, which results in relatively non-specific edematous changes to the fetus, an exudative placentitis, and characteristic targetoid hepatic necrosis of the fetal liver; and, lastly, Listeria monocytogenes, which is associated with intratrophoblastic gram-positive bacilli and a necrotizing and suppurative placentitis of both the cotyledons and the intercotyledonary spaces.

Wrapping up this case’s discussion, MAJ Travis touched on a few helpful tips regarding infectious ruminant abortions that pathologists should keep in mind when evaluating these cases. These pointers can be summarized as follows: Bacterial and mycotic infections generally compromise the placenta and deprive the fetus of oxygen/nutrients, resulting in fetal death from placental insufficiency rather than direct infection of the fetus. Viral infections, however, tend to move right on through the placenta without causing it too much damage, but will go on to infect and kill the fetus via virus-induced organ damage. In general, mares get bacterial and mycotic placentitis via cervical infection, whereas cows get bacterial or mycotic placentitis via hematogenous spread. Finally, the most important organs to collect when working up an abortion case are the placenta, abomasum or stomach fluid, liver, lung, kidney, brain, eyelid (surface and palpebral conjunctiva) from bovine fetuses especially, and serum from the dam at the time of the abortion followed by another serum sample two weeks later to check for any rise in titers.

References:

- Baszler, TV, Dubey, JP, Löhr, CV, et al. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in a free-ranging rocky mountain bighorn sheep from Washington. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:752–754.

- Buxton, D, Gilmour, JS, Angus, KW, et al. Perinatal changes in lambs infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Res Vet Sci. 1982; 32:170–176.

- Dubey, JP, Lindsay, DS. Neosporosis, toxoplasmosis, and sarcocystosis in ruminants. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2006;22:645–671.

- Gutiérrez-Expósito D, Arteche-Villasol N, Vallejo-García R, Ferreras-Estrada MC, Ferre I, Sánchez-Sánchez R, Ortega-Mora LM, Pérez V, Benavides J. Characterization of Fetal Brain Damage in Early Abortions of Ovine Toxoplasmosis. Vet Pathol. 2020;57(4):535-544.

- Lindsay, DS, Dubey, JP. Neosporosis, toxoplasmosis, and sarcocystosis in ruminants: An Update. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2020;36:205–222.

- Miller AD, Porter BF. Nervous System. In: McGavin, MD, Zachary, JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2022:930.

- Nayeri, T, Sarvi, S, Moosazadeh, M, et al. Global prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the aborted fetuses and ruminants that had an abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet Parasitol. 2021;290:109-370.