CASE III: P-2021 169 (JPC 4168027)

Signalment:

A 4-year-old, male neutered, crossbreed dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The dog was imported to the UK from Cyprus in April 2016. At that time the dog was in contact with a bitch with CTVT and in October 2020 the dog showed a firm swelling along the caudal prepuce in the ventral midline. The biopsy from the penis confirmed a CTVT. The dog was treated with vincristine with a modest reduction in size of the mass, however, the reduction was incomplete, and doxorubicin was given, but without a measurable response. Radiotherapy was given in March 2021, with some shrinkage of the penile mass. An ulcerated mass developed on the skin of the right ventral neck a month later. The dog was referred to the QVSH, University of Cambridge. On presentation, the dog was dull but responsive with a BCS 3/9. Both the penile lesion and the neck mass were evident. Abdominal ultrasound showed several, ill-defined, rounded to multilobulated, hypoechoic masses distributed throughout the liver lobes, measuring 1.56cm - 3.46cm. The penis glands showed a hypoechoic, symmetrical structure surrounding the base of the penis. Cytology of the liver nodules confirmed CTVT cells and histology of the penile glands and the skin mass confirmed CTVT. Following deterioration in the dog's condition and the onset of anorexia and vomiting, euthanasia was performed on humane grounds.

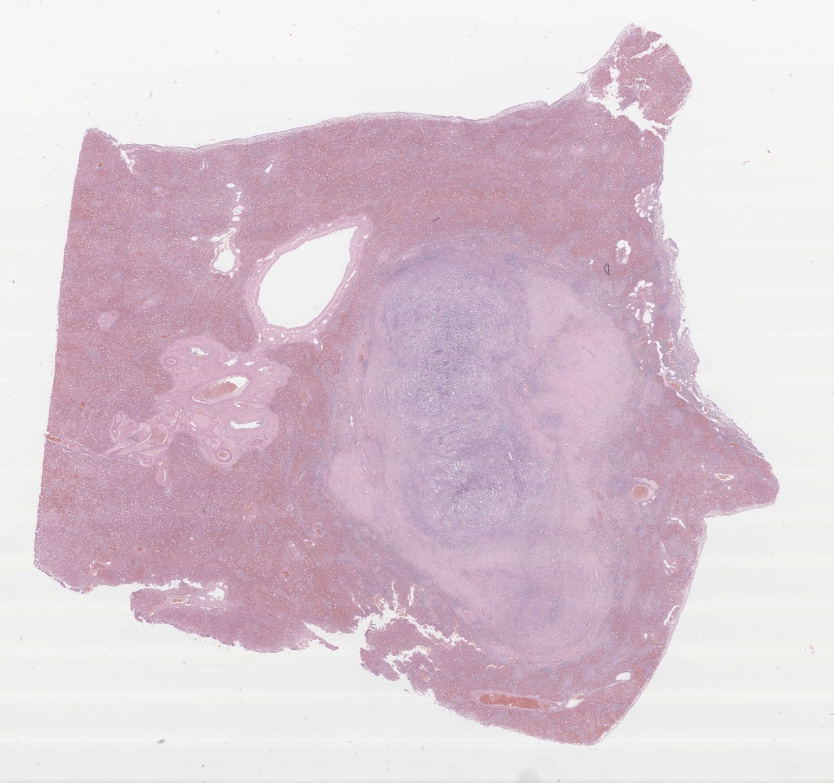

Gross Pathology:

Presented for necropsy was a 4-year-old male neutered cross breed dog. The animal was in body condition 3/9. There was a 2.5x3.5x2.5cm tumor on the skin of the right ventral cervical region. The mass was firm and had a central cavitated opening (1.4x1x1cm). The mass was mobile from the underlying subcutaneous tissues. The mass was homogeneously light cream to pink when the surface was cut, with a central 0.5x0.7x 1.1cm cavity. There was a tumor at the base of the penis 4.2x3.5x3cm on average. The tumor was firm and with an overlying intact mucosa. There was a multinodular firm tumor at the base of the penis approximately 4.2x3.5x3cm on average, well-demarcated, partially encapsulated, but locally infiltrative towards the caudal part of the base of the penis. The tumor was lined by a smooth pink to cream mucosal surface. The tumor was homogeneously cream to white. The rest of the penis had a smooth white to pink mucosal surface. The liver had multiple distinctive firm white nodular tumors with a smooth surface on the right medial lateral lobe and left lateral lobe. The masses vary from 0.3x0.5x0.4cm to 1.3x1.5x1.1cm. The masses were well-demarcated, partially encapsulated, firm, homogeneously white to light pink on cut surface. The right mandibular lymph node was 1.5x fold from the left mandibular lymph node, with a homogeneous white parenchyma on cut surface. The rest of the organs were unremarkable.

Laboratory Results:

In October 2020 biochemistry revealed an elevated ALKP 1595IU/L (reference interval 23-212). Serum biochemistry and haematology were performed; alkaline phosphatase remained elevated at 1700iu/L (26-107). There was a lymphocytopenia 0.7 x 10/9/l (reference interval 1-4.7) and an erythrocytosis RBC 9.16 X 10/12/L (5.5-8.5), Hb 22.4 (12-18) HCT 60.9% (37-55) which was unexplained.

Microscopic Description:

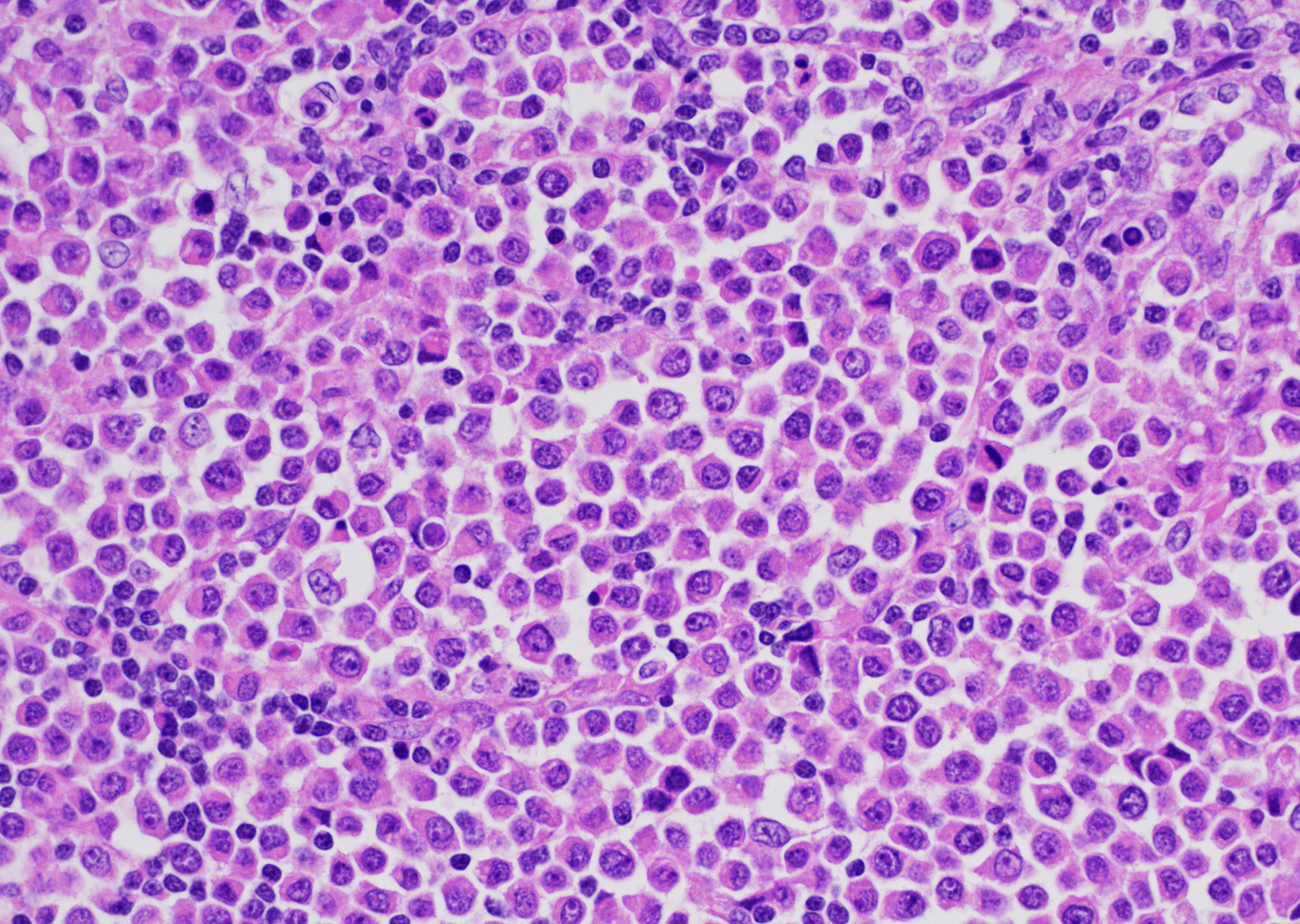

Present within the liver parenchyma is a densely cellular, locally infiltrative, mostly encapsulated neoplastic mass. Neoplastic cells are arranged in densely packed sheets that are supported by a thin collagenous stroma or more prominent fibrovascular connective tissue stroma. Individual neoplastic cells are round to oval, with scant to moderate amount of eosinophilic to light basophilic cytoplasm with variably distinct cell borders. Nuclei are large, oval to round with coarsely aggregated chromatin and variable prominent central nucleolus. Mitoses are 20 per 10 HPFs (2.37mm2), with some being bizarre. Present within a variable thick fibrous connective capsule are variable numbers of new blood vessels, lymphocytes, plasma cells and fewer neutrophils, occasional bile ducts and hepatocytes and rare giant cells. The adjacent parenchyma is compressed, with smaller hepatocytes than expected (atrophy), aggregates of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells. Portal triads exhibit variable amounts of fibrosis, moderate biliary hyperplasia, and macrophages with deposits of golden-brown intracytoplasmic material (presumed lipogranulomas). Diffusely there is moderate to severe hyperplasia and hypertrophy of hepatic stellate (Ito) cells.

Present beneath the mucosa of the penis (not submitted) is a densely cellular, moderately well-demarcated with a thin fibrous connective tissue capsule or a pseudocapsule neoplastic mass, which in some areas forms lobules. Neoplastic cells are arranged in densely packed sheets that are supported by thin collagenous or fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells are similar to the ones described above. Peripheral to the mass are small numbers of plasma cells and fewer numbers of lymphocytes. The epidermis overlying these sections of haired skin is diffusely ulcerated (not submitted). Present within the sections is a densely cellular, moderately well demarcated, non-encapsulated neoplastic mass that compresses the adjacent dermis, subcutaneous tissues, and underlying skeletal muscle. Neoplastic cells are arranged in densely packed sheets that are supported by a thin collagenous stroma or more prominent fibrovascular connective tissue stroma. Individual neoplastic cells are very similar as the ones described above. Mitoses are 29 per 10 HPFs (2.37mm2), with some being bizarre. Scattered small to moderate sized areas of necrosis and neutrophil accumulation and fibrin deposits are present throughout the mass. Multifocally peripherally blood vessels to the mass exhibit small number of plasma cells and fewer lymphocytes. The ulcerated area exhibits moderate number of viable and degenerated neutrophils, cellular debris, and fibrin deposits. The rest of the overlying epidermis and adjacent dermis is within normal limits.

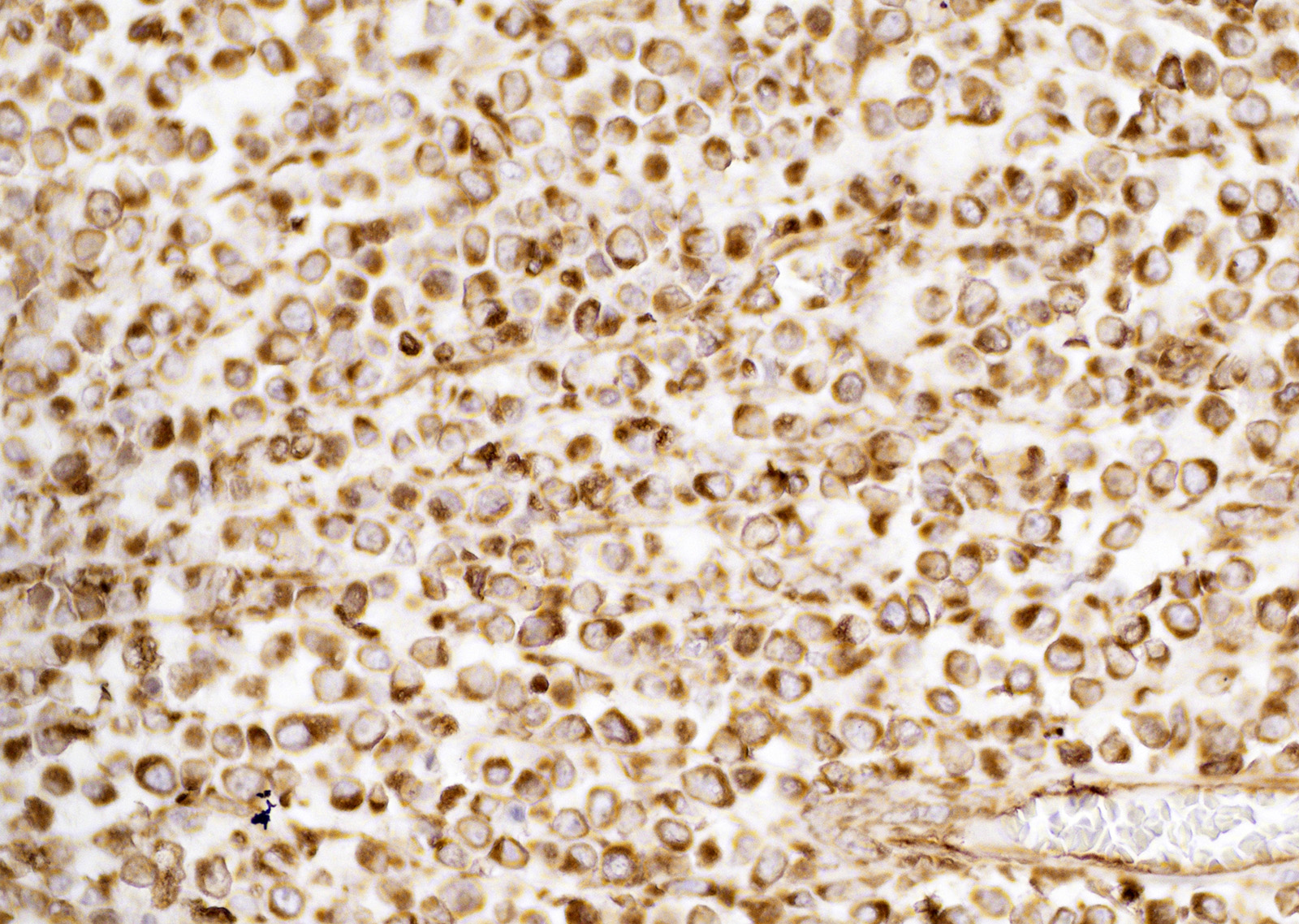

Immunohistochemistry showed neoplastic cells positive staining for vimentin. Neoplastic cells did not exhibit positive staining for CD3, CD79a, and IBA1. Neoplastic cells were negative for toluidine blue staining.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Metastatic canine transmissible venereal tumor to liver.

Contributor's Comment:

Canine transmissible veneral tumor (CTVT), also called Sticker's sarcoma, transmissible veneral sarcoma, veneral granuloma and infectious sarcoma, is a contagious tumor that propagates naturally in dogs usually during coitus, licking, sniffing, and other interaction between an affected dog and another dog.2,6,7 The other contagious known tumors are the Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease14 and a similar tumor in Syrian Hamsters.

CTVT is a naturally occurring allogenic tumor that is transmitted by living neoplastic cells from dog to dog.3,7,13 The number of diploid chromosomes in the dog is 78, whereas there are 58 or 59 chromosomes in cells of CTVT.3 Cells of the CTVT can be recognized by their chromosomes.11 CTVT is the oldest known somatic cell lineage, that arose in a single dog over 11,000 years ago and spread across continents some 500 years ago.3 CTVT may have first arisen within a genetically isolated population of early dogs whose limited genetic diversity facilitated the cancer's escape from its hosts immune systems.7 The first known report of this tumor was made in 1810 by a London veterinary practitioner. CTVT cells commonly harbor a retrotransposon upstream from the c-myc oncogene that is a molecular fingerprint for the tumour.3

CTVT has been unusual in many regards, however during the last few years more cases have been seen in countries that used to have low case numbers. CTVT has been reported from all continents except Antarctica.2 CTVT is a rare tumor in household pet dogs, but relatively common in stray dog populations in some countries, especially in tropical and subtropical regions.3

CTVT is most often present on the external genitalia, but it can be implanted on the oral cavity, nasal mucosa, conjunctival mucosa, and skin. The tumor usually develops locally in affected areas and metastases are rare, but can occur in approximately 1.5 to 6% of infected dogs12 to inguinal and iliac nodes, brain, and other viscera3 and underlying tissues such as skeletal muscle. Extragenital presentations of CTVT can occur without genital lesions. CTVT cells grow typically in the submucosa of the external genitalia, which may be ulcerated and bleeding from the site can occur. Tumors vary in size, up to 10cm in diameter3,13 and may invade underlying tissues. Regression of tumors can occur when a rich lymphocytic infiltrate is present throughout the mass within 6 months.15 However, in immunologically compromised dog's tumors can persist and metastases to distant organs can occur. Vincristine is known to be an effective treatment of CTVT, and in some cases a combination with surgery, doxorubicine or radiotherapy has been used.13 In this case unfortunately the dog failed to respond to treatment and euthanasia was performed.

CTVT cells are arranged in sheets and cords, are round or oval with scant cytoplasm that is sometimes vacuolated and have variably distinct cell borders.1 Nuclei are central, large, oval or round, coarsely aggregated chromatin and a single prominent nucleolus. Mitotic figures are common and many are bizarre.9 The supporting fibrovascular stroma is usually scant at early stages, but if the tumor is under regression the stroma is more abundant and T lymphocytes5 and other inflammatory cells are evident throughout the neoplastic tissue.

The histogenesis of CTVT cells is still poorly defined and incompletely characterized.3 Neoplastic cells are variably labelled for vimentin and CD18, further suggesting a histiocytic origin.3,9 Immunoreactivity for lysozyme and alpha-1-antitrypsin can be detected in some CTVT cells.

On routine H&E sections differential diagnoses of CTVT cells are other round cell tumors, including histiocytoma, lymphoma, and mast cell tumor, and cytological features can be subtle.1,2,3,5,6,9,11,13 Less common differential diagnoses are amelanotic melanomas and poorly differentiated carcinomas. CTVT cells usually have low nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratios and distinct small cytoplasmic vacuoles.4 Histology and cytology examination can be diagnostic for CTVT however, it is crucial to consider the tumor site and clinical history for diagnosis.2,3,4,9,11,12,13,14 The current case is an unusual presentation of a CTVT in liver and lymph nodes, being the primary neoplastic site the base of the penis. The combined use of a panel of antibodies in conjunction with microscopic assessment could facilitate the diagnosis of extragenital CTVT and difficult cases where no obvious primary tumor is present.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Medicine, The Queen's Veterinary School Hospital, University of Cambridge. Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK.

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Metastatic transmissible venereal tumor.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent synopsis of canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT), a naturally occurring parasitic allograft. This transmissible neoplasm is commonly associated with canines with free outdoor access (such as strays) and is endemic in more than 90 countries, most commonly in tropical and subtropical regions.9 Although CTVT only occurs naturally in dogs, experimental infection has been reported in other canids such as foxes, coyotes, and jackals.2

Clinically, CTVT typically exhibits a predictable cycle characterized by an initial growth phase (P phase) over 4-6 months, followed by a stable phase, and finally a regression phase (R phase), although not all tumors regress. Histologically, high numbers of mast cells and small caliber blood vessels are commonly observed at the leading margin of progressing tumors while regressing tumors have increased numbers of lymphocytes, predominantly composed of T cells. During the P phase, tumor cells typically exhibit a round cell morphology, while cells in the stable phase undergo transition from round cells to spindle cells, which become vacuolated and are associated with increased collagenous matrix during the regression phase. Unsurprisingly, mitotic counts and telemerase activity is higher during the P phase.2

Spontaneous tumor regression is predominantly mediated by the host's immune response, namely as the result of IgG antibody formation that begins after approximately 40 days of tumor growth, which also prevents reinfection in immunologically competent hosts. In addition, newborn pups born to immune dams are also resistant and achieve remission more quickly than those born to non-immune dams.2

CTVTs evade the host immune response via several mechanisms, including down regulation of their MHC genes, resulting in complete inhibition of MHC II while approximately 10% of MHC I genes are expressed. This pattern of MHC suppression without complete inhibition is crucial in regard to the neoplasm's ability to evade detection by the host's immune system as complete masking of MHC I genes tends to result in the upregulation of natural killer cell activity while a low "background" level of MHC I expression prevents this activation while also effectively masking the cells from the host's immune system. Additionally, CTVT suppresses the immune system by secreting TGF-β1 and circulating monocytes are frequently depressed up to 40%. In addition, the CTVT is associated with impaired efficiency in which mature dendritic cells are generated from monocytes and immature dendritic cells.2

As noted by the contributor, CTVT can be histologically difficult to differentiate from other round cell tumors, such as histiocytoma, lymphosarcoma, and mast cell tumors. In addition to vimentin, lysozyme, and α-1-antitrypsin CTVT cells may also demonstrate immunoreactivity for glial fibrillary acidic protein while being negative for cytokeratins, S100, and muscle markers.2

The Tasmanian devil facial tumor (TDFT) is another transmissible tumor that was first noted in 1996 and is restricted to the island of Tasmania, the only natural habitat of Tasmanian devils. Estimates from 2004-2007 estimated the disease was endemic to 70% of the island, decimating up to 90% of Tasmanian devil populations in some regions. This rapid spread is likely attributable to multiple behavioral characteristics of devils, which are non-territorial, roam up to 27km2, and also frequently bite others during feeding, fighting, and mating, facilitating transfer of transmissible tumor cells. In contrast to CTVTs which often stabilize and/or regress, TDFTs frequently occur on the face and mouth resulting in severe disfigurement and do not regress; approximately 65% undergoing metastasis to visceral organs, most commonly to the lungs.8

Histologically, TDFTs are composed of round cells and are characterized as undifferentiated, infiltrative mesenchymal neoplasms within a pseudocapsule supported by fibrovascular stroma and are often ulcerated. Initially, TDFTs were thought to be of neuroendocrine origin due to expression neuron specific enolase, synaptophysin, and vimentin. However, recent research has found tumor cells also produce periaxin, a protein specific to Schwann cells; periaxin is now considered a sensitive and specific diagnostic marker for these tumors. Given both Schwann and neuroendocrine cells are derived from the neural crest, it is likely TDFTs originated from a precursor neural crest cell.8

DFTD presents a serious risk to Tasmanian devils, which may be extinct in the wild in as few as 35 years. Given their behavioral characteristics and limited geographic distribution, few options exist to prevent their extinction short of isolating unaffected animals and culling those affected. However, recent development of a potential vaccine may offer a new approach toward thwarting the extinction of this unique species.8

References:

1. Champour M, Ojrati N, Nikrou A, Rhahimian H, et al. First report of diffuse cutaneous transmissible venereal tumor in Iran. Comp Clin Pathol. 2015;24:741-744.

2. Ganguly B, Das U, Das AK. Canine transmissible venereal tumour: a review. Vet Comp Oncol. 2013;14(1):1-12.

3. Hendrick MJ. Mesenchymal tumors of the skin and soft tissues. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Wiley Blackwell; 2017.

4. Henson KL. Reproductive system. In Atlas of Canine and Feline Cytology. W.B. Saunders Co; 2001.

5. Mizuno S, Fujinaga T, Hagio M. Role of lymphocytes in spontaneous regression of experimentally transplanted canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. J Vet Med Sci. 1994;56(1):15-20.

6. Mozos E, Mendez A, Gomez-Villamandos JC, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of canine transmissible venereal tumor. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:257-263.

7. Murchison E, Wedge DC, Alexandrov LB, et al. Transmissible dog cancer genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage. Science. 2014;343:437-440.

8. Ostrander EA, Davis BW, Ostrander GK. Transmissible Tumors: Breaking the Cancer Paradigm. Trends Genet. 2016;32(1):1-15.

9. Pashkevych I, Strybel V, Soroka N. Diagnostic methods of canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. Vet Med Sci. 2018;3:67-76.

10. Pimentel PAB, Oliveira CSF, Horta RS. Epidemiological study of canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT) in Brazil, 2000-2020. Prev Vet Med. 2021;197:105526.

11. Prier JE. Chromosome pattern of canine transmissible sarcoma cells in culture. Nature. 1966;212:725-726.

12. Rogers KS, Walker MA, Dillon HB. Transmissible venereal tumor: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1998;34(6):463-470.

13. Strakova A, Murchison E. The changing global distribution and prevalence of canine transmissible venereal tumour. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10(1):168-168.

14. Welsh JS. Contagious cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16:1-4.

15. Yang TJ, Jones JB. Canine transmissible venereal sarcoma: transplantation studies in neonatal and adult dogs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;51(6):1915-1918.