Signalment:

Gross Description:

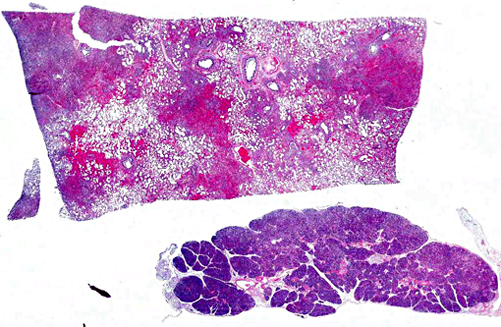

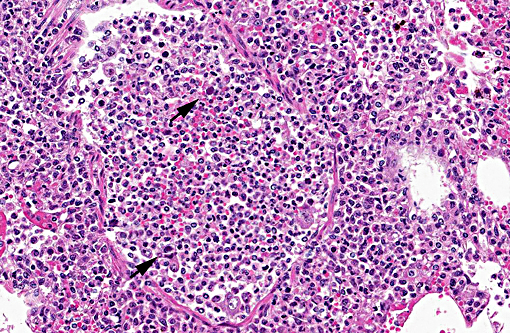

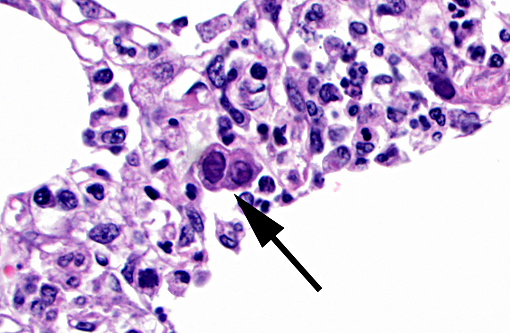

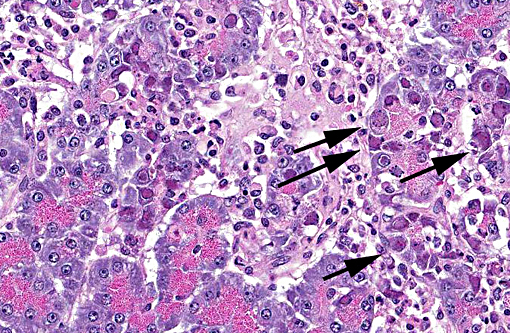

Histopathologic Description:

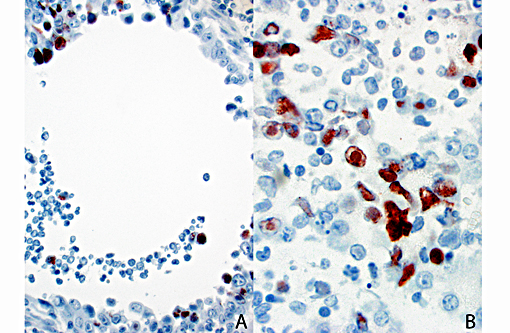

Pancreas The exocrine pancreatic cells in randomly distributed foci are pale with loss of zymogen granules, occasionally vacuolated (degeneration), or faded and shrunken. Nuclei of these cells are frequently absent and the cells are admixed with amorphous cellular debris (necrosis). There are low numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes and plasma cells within these areas and in the interstitium. Moderate numbers of acinar cells in these areas have an enlarged nucleus with marginated chromatin and an eosinophilic to basophilic inclusion similar to that described in the bronchial epithelial cells in the lung. Multifocally large areas of the surrounding adipose tissue are hypereosinophilic with absent nuclei and concentric flocculent to amorphous eosinophilic material within the adipocytes or between them (fat necrosis). There are small numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes along the periphery of these areas.

Mucocutaneous junction (not included): Multifocally there is mild parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, infrequent spongiosis, and occasional areas of ulceration. There are multifocal neutrophilic intracorneal pustules and superficial serocellular crusts composed of serum proteins and degenerate and non-degenerate neutrophils. There are multifocal areas in some sections of glabrous skin, with moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, macrophages and neutrophils surrounding the labial glands. The labial glands are often absent, degenerative, or replaced by necrotic debris and sloughed cells with few intraluminal neutrophils and debris. Rarely within these glands the nuclei are enlarged with marginated chromatin and contain a large ovoid basophilic inclusion body.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Lung: Necrosuppurative and lymphoplasmacytic bronchitis/bronchiolitis and bronchointerstitial pneumonia, multifocal to coalescing, moderate to marked, subacute with mild bronchial epithelial hyperplasia and intraepithelial intranuclear inclusion bodies (consistent with canine adenovirus type 2).

2. Pancreas: Necrotizing and lymphohistiocytic pancreatitis, multifocal, moderate, subacute with intraepithelial intranuclear inclusion bodies (consistent with canine adenovirus type 2).

Lab Results:

Bacteriology

Lung (2 specimens) - No growth and no significant growth, respectively

Liver - No growth

Spleen- Staphylococcus intermedius group (mixed culture, 1+)

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Canine adenovirus type 2 lung (respiratory epithelium, pneumocytes, alveolar macrophages), exocrine pancreas, and labial glands in the oral mucocutaneous junction - positive

Canine adenovirus type 2 small intestine - inconclusive

Canine distemper virus lung - negative

Canine parvovirus small intestine - negative

Virology

Virus isolation lung - Canine adenovirus isolated

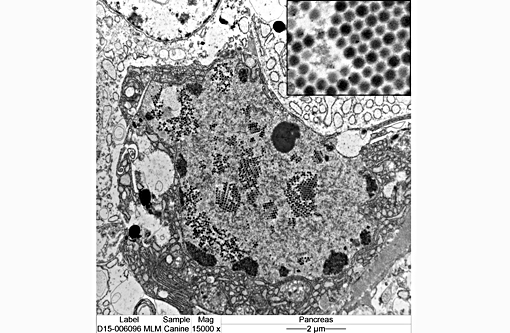

Electron Microscopy

Negative stain lung - Adenovirus

Molecular Diagnostics

Canine Respiratory Panel (PCR) Lung - Canine distemper virus - positive

Canine influenza virus - negative

Canine parainfluenza virus - negative

Canine respiratory coronavirus - negative

Canine Adenovirus 2 - positive

Canine Bordetella bronchiseptica - negative

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The extensive pulmonary infection with CAV2 resulting in dyspnea and respiratory failure in this puppy in the absence of a secondary bacterial infection is unusual. Additionally the extent of infection in this puppy including the oral labial glands at the mucocutaneous junction and exocrine pancreatic acinar cells is rare. The pattern of tissue involvement is reminiscent of that described in some immunodeficient Arabian foals with equine adenoviral infection(10) and, to the authors knowledge, involvement of the pancreas with CAV2 infections in the dog has not been previously described in the literature. However, less typical locations to identify adenoviral inclusions have been noted previously in the splenic macrophages and hepatocytes in a bulldog puppy with systemic CAV2 infection.(1) In a separate report, detection of CAV2 via in situ-hybridization in the liver and spleen and via polymerase chain reaction in the brain was noted in a puppy without inclusion bodies present in any of these tissues.(3) The exact cause of the histologic pattern in this puppy is unclear and although mutations have been noted to occur in CAV3, this virus is generally considered genetically stable(8) while the significance of mutations in terms of virulence or cell tropism is unknown.

Clinical and severe pulmonary infection with CAV2 is typically attributed to an immunocompromised status or complication with other viruses or bacteria.(1) Co-infections with CIRDC are common of which infections with multiple respiratory viruses appears to be more common than previously believed.(12,14) In this puppy, both canine distemper virus (CDV) and adenovirus were detected by PCR of lung tissue but interestingly there was no immunoreactivity noted in the lung on CDV IHC and a lack of viral inclusions consistent with CDV. Although PCR and IHC testing of CDV has not been directly compared, the higher sensitivity of PCR over IHC has been noted in another veterinary infectious disease(2) and inclusion bodies were only found in 25% of CDV cases confirmed by other methods in another report7 which may explain the findings in this case. The contribution of CDV in this case is unknown and assuming that the lack of histologic or immunohistochemical detection suggests a low viral load, one of two following scenarios is likely: 1. Early infection prior to significant viral replication and cytopathic effects, or 2. Late infection after significant but incomplete clearance of the virus. With either of these scenarios, the degree of virus-induced immunosuppression can be questioned as the former is before the lymphoid destruction that induces immunosuppression and the latter would imply enough recovery of the immune system to allow significant clearance of the virus. Other reasons for possible immunosuppression also existed in this puppy including recent steroid usage and others conditions including marked lymphangiectasia with hypoproteinemia and evidence of an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. The occurrence of clinical infection in this vaccinated puppy is likely attributable to interference of maternal antibodies which typically persist until 12-14 weeks of age (2-4 weeks beyond this puppies last vaccine) rather than emergence of a variant strain.(8,13)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Lung: Pneumonia, bronchointerstitial, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe with numerous intraepithelial intranuclear viral inclusion bodies, Rottweiler mix, canine.

2. Pancreas: Pancreatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with numerous intraepithelial intranuclear viral inclusion bodies.

3. Adipose tissue, peripancreatic and mesenteric: Fat necrosis, multifocal to coalescing, with saponification.

Conference Comment:

Canine adenovirus type 2 is most often associated with mild respiratory disease, although more severe fatal disease has been documented.(1) This dogs history included vaccination only up to 8 weeks, as well as administration of corticosteroids, both of which were suggested as playing a role in the pathogenesis in this case. The differential diagnosis for viral pneumonia in the dog discussed by participants included: canine morbillivirus, canine influenza virus, canine coronavirus and canine parainfluenza virus. In this case, the intranuclear viral inclusion bodies within epithelial cells are considered distinctive for canine adenovirus type 2, making other viral etiologies less likely. Some participants speculated that a secondary bacterial infection also may have contributed to the pulmonary changes in this dog.

Viruses are well-known to play a role in the pathogenesis of bacterial pneumonias by damaging the respiratory epithelium, inhibiting bacterial clearance and facilitating bacterial adhesion. Other participants commented that a contributing bacterial etiology likely would have resulted in a more neutrophil-rich inflammatory component in the lung. Bacterial agents of canine infectious respiratory disease include Bordetella bronchiseptica, Mycoplasma spp., and Streptococcus equi sp. zooepidemicus.(14)

The pancreatic involvement in this case is uncommon in typical infections with canine adenovirus. Pancreatitis due to adenovirus infection is well documented in nonhuman primates; adenoviral infection in a number of non-human primate species can result in pancreatic necrosis and fibrosis with chronic-active inflammation. Pancreatic involvement typically occurs in more clinically severe cases, typically with underlying immunosuppression; other lesions also include hepatitis and nephritis. Adenovirus infection in immunocompetent nonhuman primate hosts usually presents as self-limiting respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.(9) Fowl adenovirus, a common disease in chickens, results in necrotizing pancreatitis, gizzard erosion, and inclusion body hepatitis.(11)

We appreciate the excellent supporting materials with the submission, including laboratory data, gross, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy images. These additional materials greatly enhances the teaching value of this case.

References:

1. Almes KM, Janardhan KS, Anderson J, Hesse RA, Patton KM. Fatal canine adenoviral pneumonia in two litters of Bulldogs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010;22: 780784.

2. Baszler TV, Gay LJ, Long MT, Mathison BA. Detection by PCR of Neospora caninum in fetal tissues from spontaneous bovine abortions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37: 40594064.

3. Benetka V, Weissenbock H, Kudielka I, Pallan C, Rothm+â-+ller G, M+â-¦stl K. Canine adenovirus type 2 infection in four puppies with neurological signs. Vet Rec. 2006;158: 9194.

4. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:166.

5. Bulut O, Yapici O, Avci O, Simsek A, Atli K, Dik I, Yavru S, Hasircioglu S, Kale M, Mamak N. 2013The Serological and Virological Investigation of Canine Adenovirus Infection on the Dogs. The Scientific World Journal 2013 Sep 24;2013:587024. doi: 10.1155/2013/587024. eCollection 2013.

6. Buonavoglia C, Martella V. Canine respiratory viruses. Vet Res 2007:38; 355373.

7. Dami+â-ín M, Morales E, Salas G, Trigo FJ. Immunohistochemical Detection of Antigens of Distemper, Adenovirus and Parainfluenza Viruses in Domestic Dogs with Pneumonia. J Comp Pathol 2005:133; 289293.

8. Decaro N, Martella V, Buonavoglia C. Canine Adenoviruses and Herpesvirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2008:38; 799814.

9. Mansfield KG, Sasseville VG, Westmoreland SV. Molecular localization techniques in the diagnosis and characterization of nonhuman primate infectious diseases. Vet Pathol. 2014:51(1);1101-26.

10. McChesney AE, England JJ, Adcock JL, Stackhouse LL, Chow TL. Adenoviral infection in suckling Arabian foals. Vet Pathol 1970:7; 547564.

11. Ono M, Okuda S, Yazawa Y et al. Adenoviral gizzard erosion in commercial broiler chickens. Vet Pathol. 2003:40; 294-303.

12. Rodriguez-Tovar LE, Ram+â-¡rez-Romero R, Valdez-Nava Y, Nev+â-írez-Garza AM, Z+â-írate-Ramos JJ, L³pez A. Combined distemper-adenoviral pneumonia in a dog. Can Vet J. 2007:48; 632634.

13. Sykes JE. Canine Viral Respiratory Infections. In: Sykes JE, ed. Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:170-181.

14. Viitanen SJ, Lappalainen A, Rajam+â-ñki MM. Co-infections with Respiratory Viruses in Dogs with Bacterial Pneumonia. J Vet Intern Med. 2015:29; 544551.

15. Wright N, Jackson FR, Niezgoda M, Ellison JA, Rupprecht CE, Nel LH. High prevalence of antibodies against canine adenovirus (CAV) type 2 in domestic dog populations in South Africa precludes the use of CAV-based recombinant rabies vaccines. Vaccine. 2013:31; 41774182.