Signalment:

Gross Description:

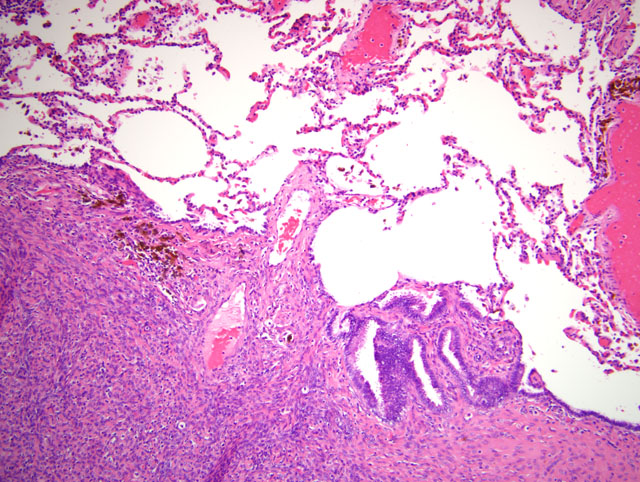

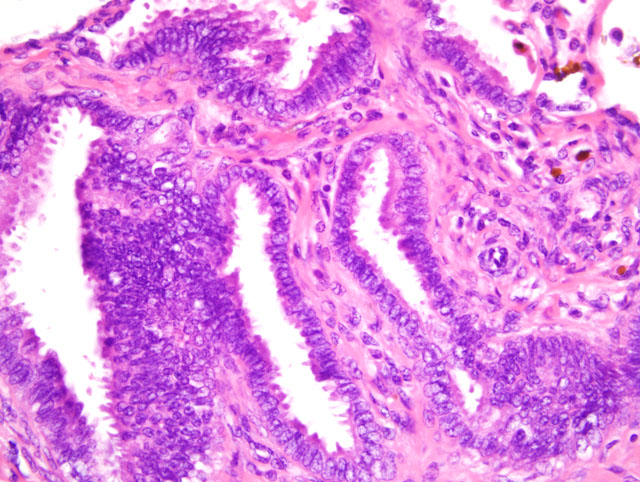

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Spontaneous endometriosis has been studied in rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques and baboons, although the disease has also been reported in other captive and wild species.(3) Risk factors examined for the development of spontaneous endometriosis in nonhuman primates include maternal age, parity, captivity and experimental procedures such as laparoscopies, hysterectomies, and treatment with estradiol implants.(3) Nonprimates (e.g. rats, syngenic mice, nude mice, hamsters and rabbits) do not develop spontaneous disease, but the disease has been experimentally induced in them.(6)

In the present case, metastasis of endometrial cells by lymphatic and/or hematogenous routes could have disseminated the endometriosis to the thorax. To the authors knowledge, endometriosis has not been reported in sooty mangabeys, and only one case of endometriosis in lung has been reported in a rhesus macaque.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Because foci of endometriosis respond to hormonal stimulation with periodic bleeding, the diagnosis is not always straightforward, as mentioned by the contributor. In some cases, lesions consist only of endometrial stroma and areas of hemorrhage or hemosiderin; longstanding lesions may be obscured by secondary fibrosis.(2) A rather atypical example with decidualized stromal cells from a rhesus macaque on a therapeutic course of Depo-Provera-� (medroxyprogesterone acetate) was reviewed in WSC 2007-2008, Conference 10, case III. In cases lacking the distinctive features of endometriosis described by the contributor, the differential diagnosis may include retroperitoneal fibromatosis and neoplasia of mesenchymal origin. In such cases, immunohistochemistry may be useful; endometriotic stromal cells exhibit markedly upregulated estrogen production due largely to high levels of the aromatase enzyme, which is absent in normal endometrial stroma. Interestingly, high levels of such proinflammatory cytokines as prostaglandin E2, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor are also noted in endometriosis. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates local estrogen synthesis, and endometriotic tissue is resistant to the antiestrogenic effect of progesterone; therefore, the overall inflammatory and endocrine milieu in endometriotic tissue is characterized by the overproduction of estrogen and prostaglandin and resistance to progesterone.(2)

Conference participants discussed the two predominant theories for the development of endometriosis, i.e. the metastatic theory and the metaplastic theory. The former postulates that endometrial tissue is physically transplanted to extrauterine locations through: retrograde menstruation, with subsequent spread to the peritoneum; surgical procedures, with subsequent spread to the cervix, vagina, and laparotomy scars; or metastasis via blood and lymphatic vessels. The metaplastic theory suggests that endometrial tissue arises directly from cell rests in the mesothelium, from which the M+�-+llerian ducts arise during embryogenesis.(2) The mechanism by which endometriosis developed in the lung of the sooty mangabey in this case is unclear. Participants considered hematogenous dissemination, but based on the generally peripheral distribution of the lesions in the sections examined, many speculated that direct extension from the abdominal cavity through the esophageal hiatus, aortic hiatus, or caval opening could have occurred.

In addition to the microscopic features described by the contributor, conference participants noted individualized round cells scattered throughout the endometrial stroma characterized by round, hyperchromatic nuclei and small amounts of cytoplasm containing brightly eosinophilic globules. The round cells are interpreted as endometrial stromal granulocytes, which are likely large granular lymphocytes that reach peak numbers during the secretory phase, the onset of which is marked by ovulation.(7)

References:

2. Ellenson LH, Pirog EC: The female genital tract. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, 8th ed., pp. 1028-1029. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2010

3. Hadfield RM, Yudkin PL, Coe CL, Scheffler J, Uno H, Barlow DH, Kemnitz JW, Kennedy SH: Risk factors for endometriosis in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): a case-control study. Hum Reprod Update 3:109-115, 1997

4. Lowestine LJ: A primer of primate pathology: lesions and nonlesions. Toxicol Pathol 31:92-102, 2003

5. McClure HM, Graham CE, Guilloud NB: Widespread endometriosis in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Proc 2nd Int Congr Primatol 3:155-161, 1969

6. Story L, Kennedy S: Animal studies in endometriosis: a review. ILAR J 45:132-138, 2004

7. Young B, Lowe JS, Stevens A, Heath JW: Wheaters Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Guide, 5th ed., p. 373. Elsevier Limited, Philadelphia, PA, 2006