Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 2

September 5th, 2018

CASE III: VPL 1 (JPC 4066919-00).

Signalment: A 12-year-old female spayed Galgo Español, dog, Canis lupus familiaris

History: During a routine dental cleaning procedure, a polypoid pedunculated mass on the left palatine tonsil was discovered. The mass has been removed surgically. There have been no other signs of illness during clinical examination.

Gross Pathology: Submitted by referring veterinarian. Petechiation was seen throughout the omentum. There were petechiae in the abomasum which was also filled with brownish blood-tinged fluid. There were petechiae and ecchymoses on pericardium, epicardium and endocardium.

Laboratory results: None.

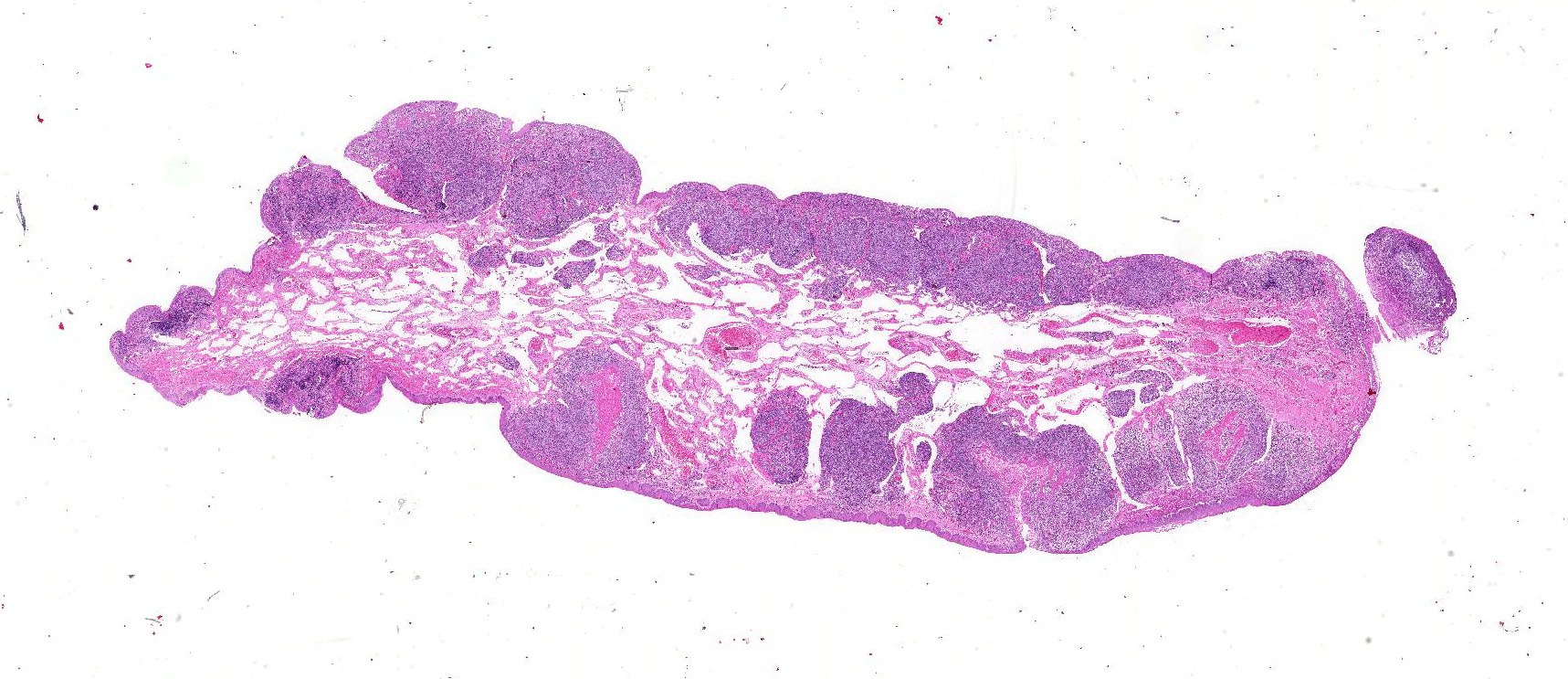

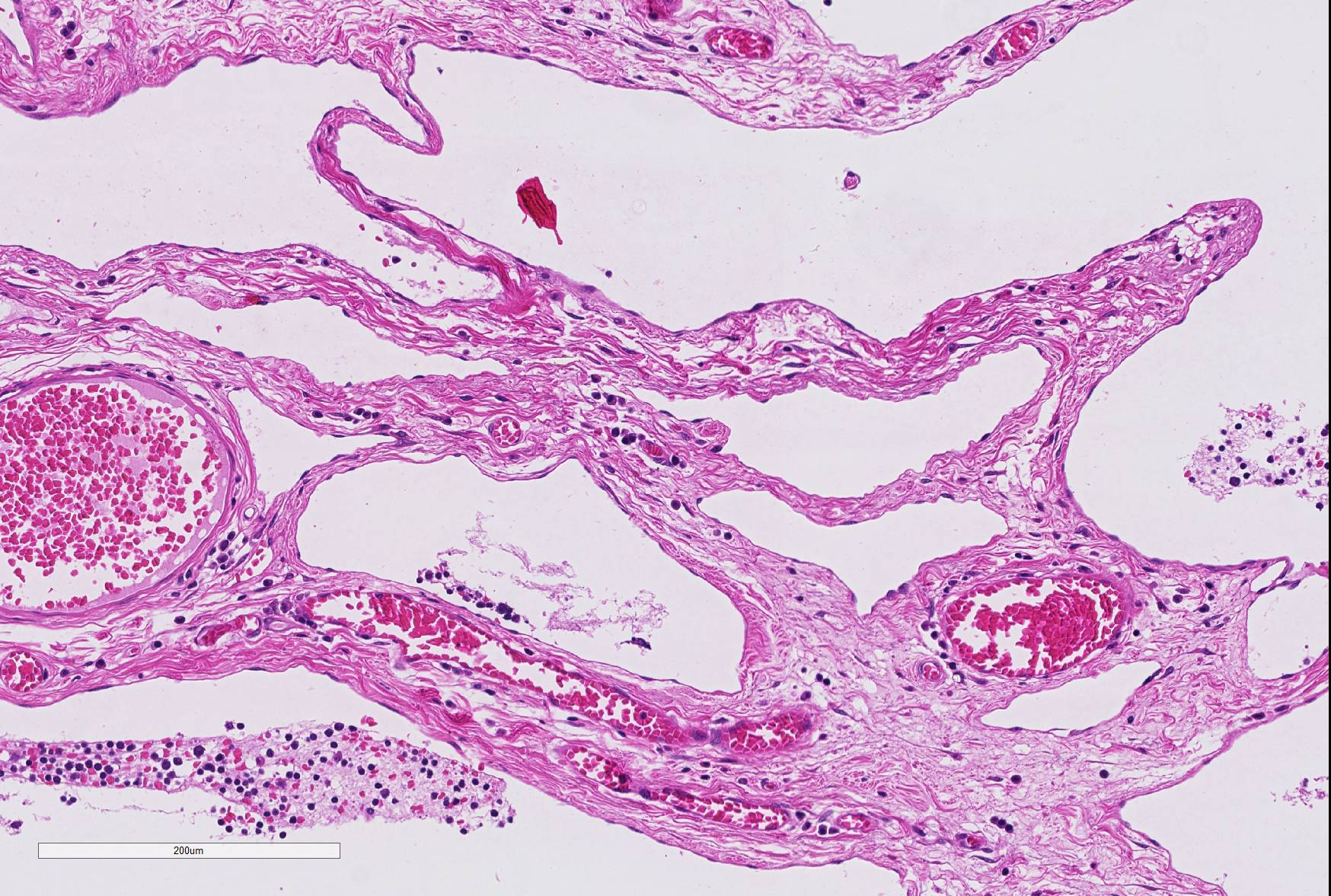

Microscopic Description: The mass mainly consists of soft tissue and is covered by a nonkeratinized pluristratified epithelium showing variable degrees of hyperplasia. The epithelium multifocally shows mild to moderate intracellular oedema and there also is a mild to mainly moderate epitheliotropism of mainly lymphocytes but also some neutrophils. Multifocally, the epithelium tends to form crypts which are filled with an eosinophilic material, scaled off epithelial cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils and cellular debris. There are multiple densely-arranged subepithelial areas consisting of mononuclear cells, which can be identified as well-differentiated slightly anisocytotic lymphocytes and a few plasma cells. Partially, the lymphocytes form follicular nodules which show an appearance of primary and secondary lymphoid follicles. Altogether, the histomorphologic structures resemble tonsillar tissue, which is consistent with the localization of the tumor. The center of the mass is formed by collagenous connective tissue, which shows mild to moderate edema. Embedded in that fibrous stroma, numerous dilated and ectatic vascular structures can be seen. Some of them are filled with erythrocytes and resemble arterial and venous blood vessels. Others, mostly thin-walled, are filled with varying amounts of slightly eosinophilic fluid and a few cellular components (lymphocytes and macrophages) or they appear to be empty. These vascular structures may be identified as lymphatic vessels. All of the vessels are lined by a one-layered well-differentiated endothelium. In some slides, there are seromucous glands at the base of the mass, which seem to be salivary glands.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Tonsil: lymphangiomatous tonsillar polyp

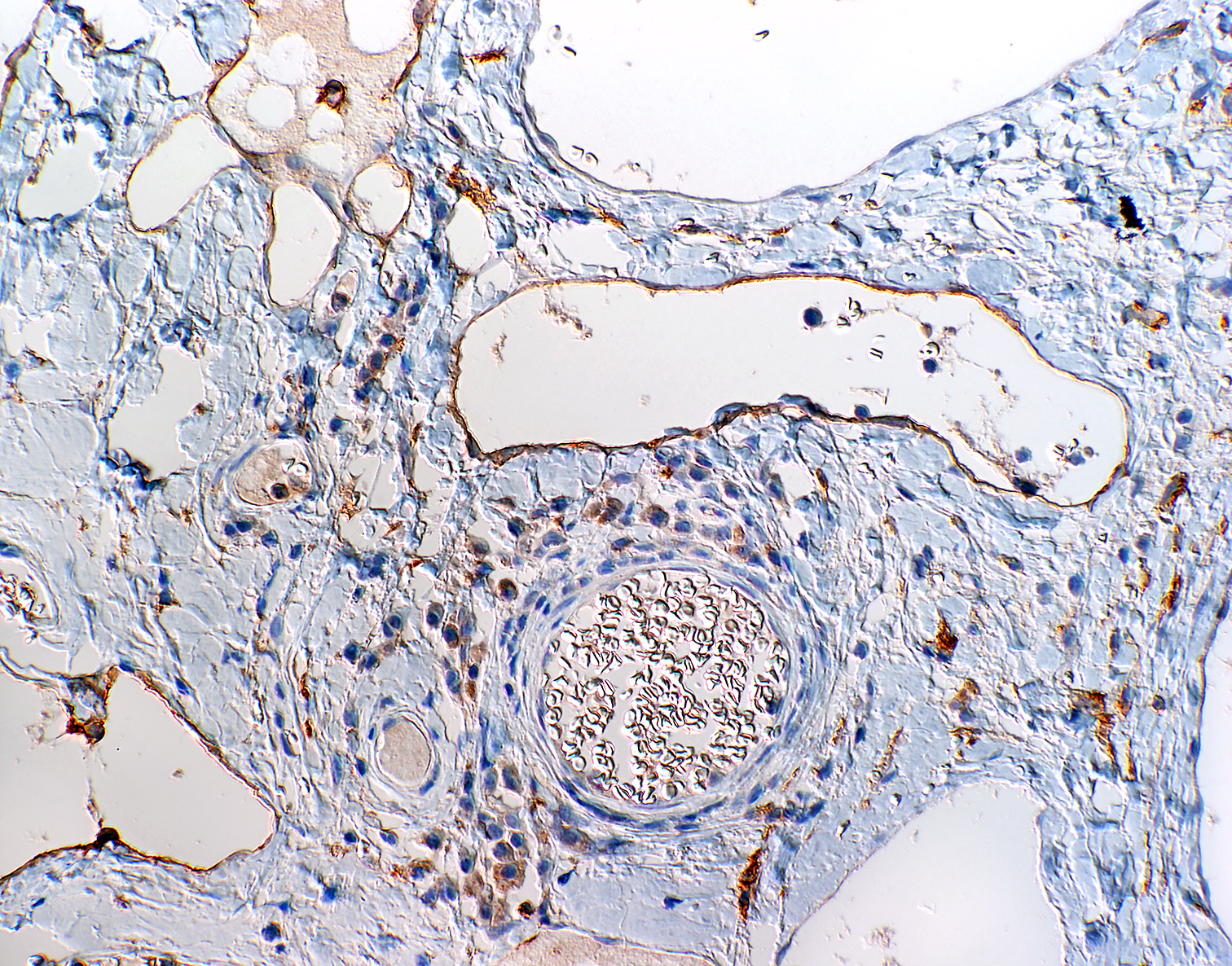

Contributor’s Comment: To characterize the involved cellular components an immunohistological examination was performed. The lymphocytes were immunopositive for CD3 and CD79a and showed the expected distribution patterns for tonsillar tissue. Some of the cells mostly adjacent to small vessels or inside of supposedly lymphatic vessels could be identified as macrophages via expression of MAC387 and lysozyme. While blood vessels often could easily be identified due to the presence of intravascular erythrocytes or thick vascular walls, there were some difficulties in the direct differentiation of lymphatic vessels and thin-walled venous vessels, especially when they appeared to be empty. For that reason, the endothelium was immunolabeled using markers specific for lymphatic endothelium (LYVE-1 and Prox1.9 While not all lymphatic vessels were immunopositive regarding LYVE-1 (Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1), Prox1 (Prospero homeobox 1) was widely expressed by the lymphatic vessels in the tissue sample, which is consistent with the findings of previously performed studies on immunohistochemical labelling of blood and lymphatic vessels in dogs9.

The pathogenesis of lymphangiomatous tonsillar polyps is still unclear. There are different theories about the origin of this benign proliferation. Because of the haphazard proliferation of components which are usually found in the tonsil they are discussed to be hamartomatous proliferations5 and therefore classified as malformations. One author sees them as the result of lymphatic obstruction with consecutive congestion and mucosal prolapse finally forming the polyp11. In veterinary medicine those polyps are also considered being a result of chronic recurrent tonsillitis and are regarded as inflammatory polyps which occur infrequently in old dogs5. Anyhow, the definite cause remains uncertain.

As in this case such polyps are often undiscovered for a long period of time. They can be asymptomatic or, probably when large enough, they may cause dysphagia6, non-productive cough11 or a sore throat1. In human medicine, the complete surgical excision is normally curative and there usually are no recrudescences.5

This case shows that such benign proliferations might be considered as differential diagnosis when there is a unilateral mass of the tonsils, especially concerning tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma, even though regional lymph nodes are usually enlarged early in such cases.7

JPC Diagnosis: Tonsil: Lymphangiomatous polyp.

Conference Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent review of this uncommon but morphologically unique lesion often seen in association with chronic tonsillitis in older dogs.

The tonsil samples antigens which are dissolved in the saliva, and develops immune responses akin to other lymphoid organs throughout the body. A layer of nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium provide barrier function for the tonsil.10

A unique feature of the tonsils is their lack of afferent lymphatic vessels. This prevents them from being effective lymphoid filter for structures in the oral cavity (which drains instead primarily to pharyngeal and submandibular nodes)3, but also significantly reduces the possibility of finding metastatic tumors within the tonsils. As a general rule, tonsillar neoplasms arise from tissues native to the tonsil itself- squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and rare tumors of the vascular and lymphatic endothelium.

The tonsils also serve as a reservoir or portal vein treated for a variety of viral and bacterial agents.10 A number of viral agents including pseudorabies in swine and parvovirus in carnivores may utilize the tonsil as an initial site of replication and dissemination. Depending upon the particular virus and stage infection, either involution or hyperplasia of tonsillar follicles may be the result. A significant percentage of swine carry Erysipelothrix rhusiopathae, Streptococcus suis, and various species of salmonellae within the tonsils as well.10 Additionally, the scrapie-associated prion protein has been identified in tonsillar tissue as well.10

The lymphoid changes seen in the tonsils parallel those seen in reactive lymph nodes with a number of primary follicles surrounding tonsillar crypts. Following antigenic stimulation, development of secondary follicles with mantle zones extending in the direction of the antigenic stimulus will occur, as well as marked expansion of the interfollicular lymphoid tissue. The majority of histologic changes seen in the biopsy samples of excised tonsils will be chronic in nature; acute tonsillitis is rarely if ever seen. The presence of neutrophils within crypts, crypt epithelium and most importantly with in the parenchyma of the tonsils is required for the diagnosis of acute tonsillitis. The histologic changes of chronic tonsillitis are indistinguishable in most cases from tonsillar hyperplasia.

An appropriate ruleout in this case would be that of a lymphangioma. Lymphangiomas are uncommon benign proliferations of lymphatic derived thin walled cystic spaces often filled with pink, watery proteinaceous fluid.12 These benign tumors may be found as isolated findings in lymphoid tissues including the lymph node and spleen. The abundant fibrous connective tissue seen in lymphangiomatous polyps is generally not a feature of lymphangiomas, and provides additional support as tonsillar lymphangiomatous polyps are hamartomatous lesions rather than true neoplasms.5

A very interesting, morphologically distinct lesion of lymphoid tissue that is occasionally seen in the dog and cat is vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses (previously referred to as nodal angiomatosis). This lesion has not yet been reported in the tonsil as of yet. Gelberg and Valentine reported this change in association with thyroid carcinoma in a dog. 4 Vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses is a pressure-induced non-neoplastic conversion of nodal sinuses into anastomosing vascular channels. The inciting pressure is often the result of obstruction of venous or hilar lymphatic drainage and has been reported in humans in association with a variety of neoplasms, as well as various forms of venous obstruction. Vascular transformation may take a variety of appearances believed to be the result of a continual related to the duration and degree of venous or lymphatic obstruction.4 The plexiform pattern, the most commonly reported in animals, presents as a mass lesion composed of interconnected mature vascular channels, a flat endothelial cell lining, and a low mitotic rate.10 More chronic cases are associated with increased amounts of collagen separating proliferating vessels. In a second variant, the round vascular type, vascular changes are usually empty or contain amorphous material presumed to be lymph10. A recently published review by Xu et al., excellently describes this and other vascular and stromal proliferations in the lymph nodes of humans. 12

Contributing Institution:

Institute of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Leipzig, Germany

http://patho.vetmed.uni-leipzig.de

References:

1. Al Samarrae SM, Amr SS, Hyams, VJ. Polypoid lymapangioma of the tonsil: report of two cases and review of the literature. J of Laryngol Otol 1985; 99(8): 819-823.

- Bauchet A, Balme E, Thibault J, Fontaine J, Cordonnier N. Lympahgiectatic fibrous polyp of the tonsil in a dog. ECVP/ESCVP 2009 Proceedings; 141(4):284.

- Gelberg HB. Alimentary system and the peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, and peritoneal cavity. In: Zachary, JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 6th ed. 2017. St. Louis, MO, pp. 324-411.

- Gelberg HB, Valentine BA. Lymphadenopathy associated with a thyroid carcinoma in a dog. Vet Pathol 2011; 48(2): 530-534.

- Kardon DE, Wenig BM, Heffner DK, Thompson LDR. Tonsillar lymphangiomatous polyps: a clinocopathologic series of 26 cases. Mod Pathol 2000; 13(10):1128-1133.

- Kuhnemund M, Wernert N, Gevensleben H, Gerstner AO. Lympahgiomatoser Tonsillenpolyp. HNO 2010; 58(4):409-412.

- Meuten DJ, ed.. Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th ed. 2002; Ames IA; Iowa State Press.

- Miller A, Alcaraz, A, McDonough S. Tonsillar lymphangiomatous polyp in an adult dog. J Comp Pathol 2008; 138(4): 215-217.

- Sleeckx N, van Brantegem L., Fransen E. Evaluation of immunohistochemical markers fo lymphatic and blood vessels in canine mammary tumors. J Comp Pathol 2013; 148(4): 307-317.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hotstetter JM. Alimentary System, In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed. 2016; St. Louis MO, Elsevier Press, vol 2, p. 20

- Visvanathan PG. A pedunculated tonsillar lymphangioma. J Laryngol Otol 1971; 85(1):93-96.

- Xu ML, O’Malley D. Lymph node stromal and vascular proliferations. Seminars Diagn Pathol 2018; (67-75).