Signalment:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

While the conference moderator and vast majority of conference participants concurred with the contributors diagnosis of OSA, none of the slides evaluated by the attendees contained blood-filled spaces lined by neoplastic osteoblasts, the histologic features diagnostic for the telangiectatic subtype. The gross appearance of telangiectatic osteosarcoma is distinctive, and reflects multiple blood-filled spaces reminiscent of hemangiosarcoma; the contributor did not provide a gross description of the bone tumor in this case.

Osteosarcoma represents the single most common primary neoplasm of the appendicular skeleton in dogs and cats, where it accounts for 80% and 70% of primary bone neoplasms, respectively. In dogs, OSA is characterized by rapid progression and early metastasis to the lungs, resulting in an early and high mortality rate. The appendicular skeleton is affected far more commonly than the axial skeleton, and the forelimbs are affected more commonly than the hind limbs. The neoplasm exhibits a strong predilection for the metaphyses of the distal radius, proximal humerus, distal femur, and proximal tibia.(2,3)

Osteosarcoma can be categorized based on its site of origin, with the majority of tumors being central, i.e. arising within bones, and fewer being categorized as one of two types of peripheral OSA, i.e. arising within the periosteum. Peripheral osteosarcoma includes the periosteal subtype, which clinically behaves similar to central OSA; and parosteal OSA, which is slower-growing and more well-differentiated, with a more favorable overall prognosis. The conference moderator cautioned participants that, because of the marked intratumoral histologic variability, OSAs can be difficult to accurately classify; nevertheless, subclassification into one of six categories based on the predominant histologic pattern is well-described in veterinary pathology, and summarized below:(2,3,4)

- Poorly differentiated: undifferentiated neoplastic cells range from primitive mesenchymal to large and pleomorphic; identification as OSA depends on identifying small quantities of tumor osteoid; highly aggressive, osteolytic tumor frequently associated with pathological fractures

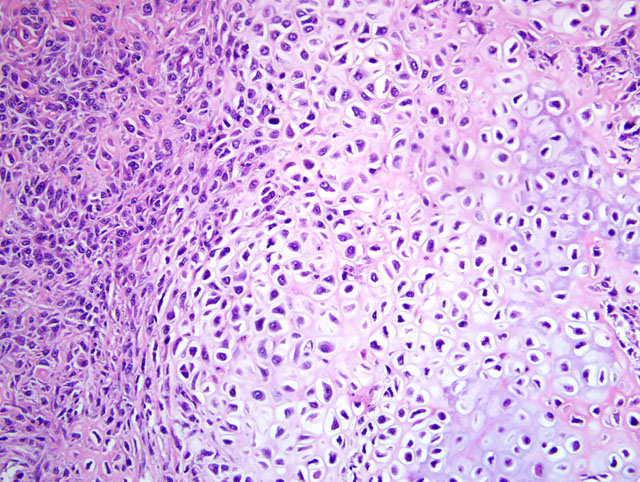

- Osteoblastic: anaplastic osteoblasts with angular cell borders, variable amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, and hyperchromatic, often eccentric nuclei predominate; further subclassified as nonproductive or productive based on presence or absence of tumor bone production

- Chondroblastic: neoplastic cells produce both prominent chondroid and osteoid matrices

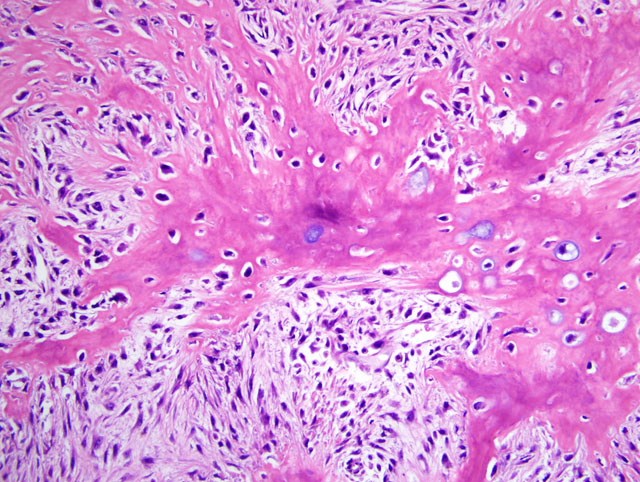

- Fibroblastic: interlacing fascicles of spindle shaped cells, resembling those of fibrosarcoma, that produce osteoid or tumor bone

- Telangiectatic: subtype associated with the least favorable prognosis; consists of solid areas and large blood-filled spaces lined by malignant osteoblasts that occasionally form spicules of osteoid

- Giant cell: tumor giant cells predominate in large areas of the neoplasm, which otherwise resembles nonproductive osteoblastic OSA

References:

2. Thompson K: Bones and joints. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 112-118. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

Thompson KG, Pool RR: Tumors of bones. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 4th ed., pp. 263-290, Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames, IA, 2002

Unni KK, Inwards CY, Bridge JA, Kindblom LG, Wold LE: Tumors of the Bones and Joints, AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 4th series, vol. 2, ed. Silver Spring, MD, pp. 119-192. American Registry of Pathology, Washington, DC, 2005