WSC 23-24, Conference 8, Case 4

Signalment:

1-year-old, Gypsy Vanner colt (Equus caballus)

History:

The patient presented for acute recumbency and was treated in the field with antimicrobials, plasma, and IV fluids. He was unable to rise but would sit in sternal recumbency and would eat when offered hay. On presentation, he was in lateral recumbency on the trailer, but was able to stand when assisted with the sling. He was severely underweight with muscle wasting. His heart rate was 80 bpm with a systolic murmur, his respiratory rate was 40 bpm, and his rectal temperature was 98.5 ºF. Mucous membranes were pale with a capillary refill time of 2 seconds.

Thoracic ultrasound revealed mild pneumonia (comet tailing cranioventrally) with a small amount of pleural fluid. Abdominal ultrasound revealed edema in the wall of the colon, small intestine, and cecum along with a moderate amount of fluid within the cecum and colon. A small amount of peritoneal fluid was present.

Medical therapy consisted of IV fluids, ceftiofur, flunixin, vitamin E, and supportive care. Two days after presentation, the patient was found colicking and abdominal radiographs at that time revealed a large amount of intestinal sand. He began passing large amounts of diarrhea but continued to have a good appetite and remained standing (assisted with sling). A plasma transfusion was given, but the patient continued to have profuse watery diarrhea and began to slowly decline over the next 36 hours. Two days later he became increasingly dull and spontaneously died.

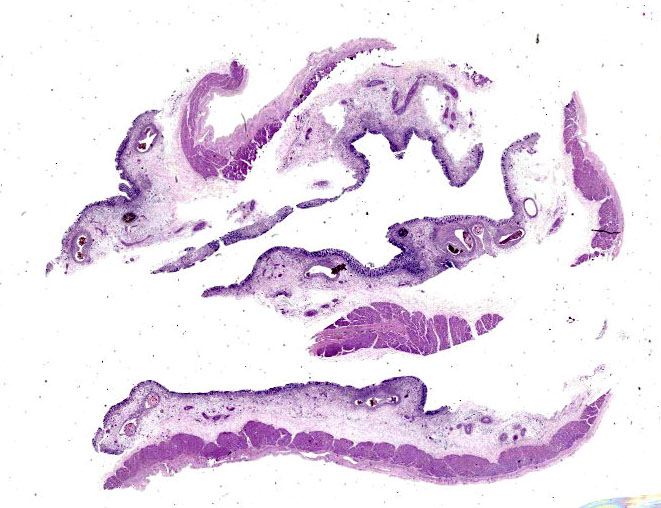

Gross Pathology:

The cecal and ventral colonic mucosa contains numerous widespread multifocal, brown to red, 1-2 mm diameter circular nematodes. In the region of the diaphragmatic flexure, the right dorsal colon contains a moderate amount of wet, packed, tan, granular material (sand) admixed with numerous 8-5 x 1 mm red round nematodes and a small amount of green fibrous ingesta. The wall of the cecum and ventral colon is mildly to moderately expanded by clear gelatinous material. Numerous pinpoint red foci are present within the mucosa of the dorsal colon.

Laboratory Results:

Complete blood count:

WBC = 12,700/µL

Fibrinogen = 600 mg/dL

Serum chemistry:

Total protein = 5.6 g/dL (6.1-8.4)

Albumin = 2.2 g/dL (2.7-4.5)

Potassium = 5.6 mEq/L (2.2-5.3)

Sodium = 130 mEq/L (136-144)

Chloride = 94 mEq/L (96-105)

Fecal float: Negative.

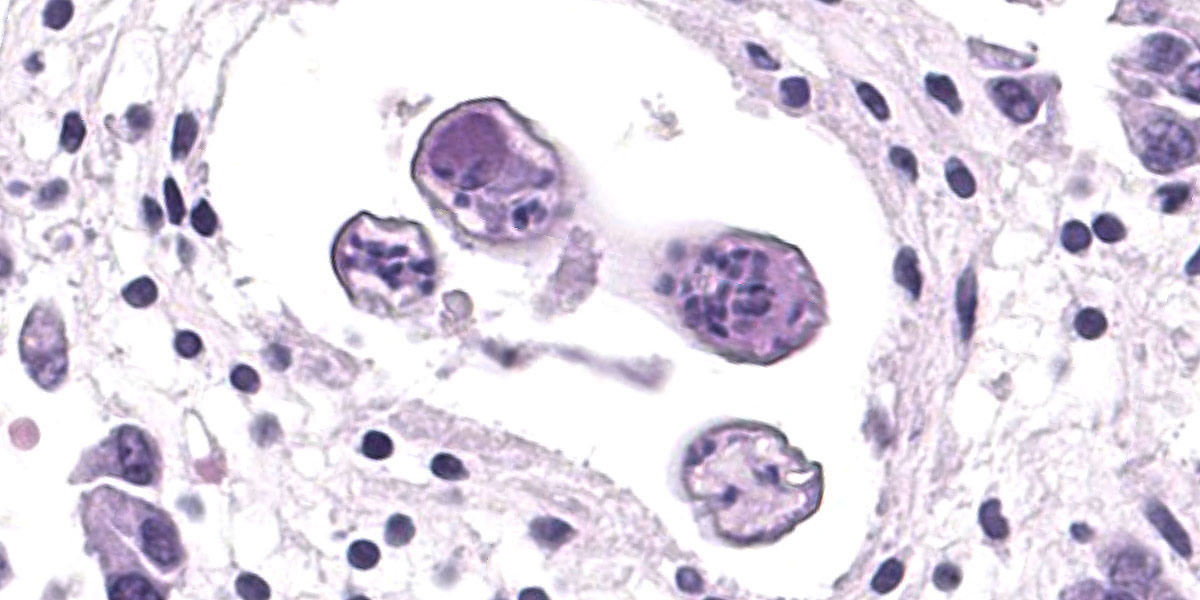

Microscopic Description:

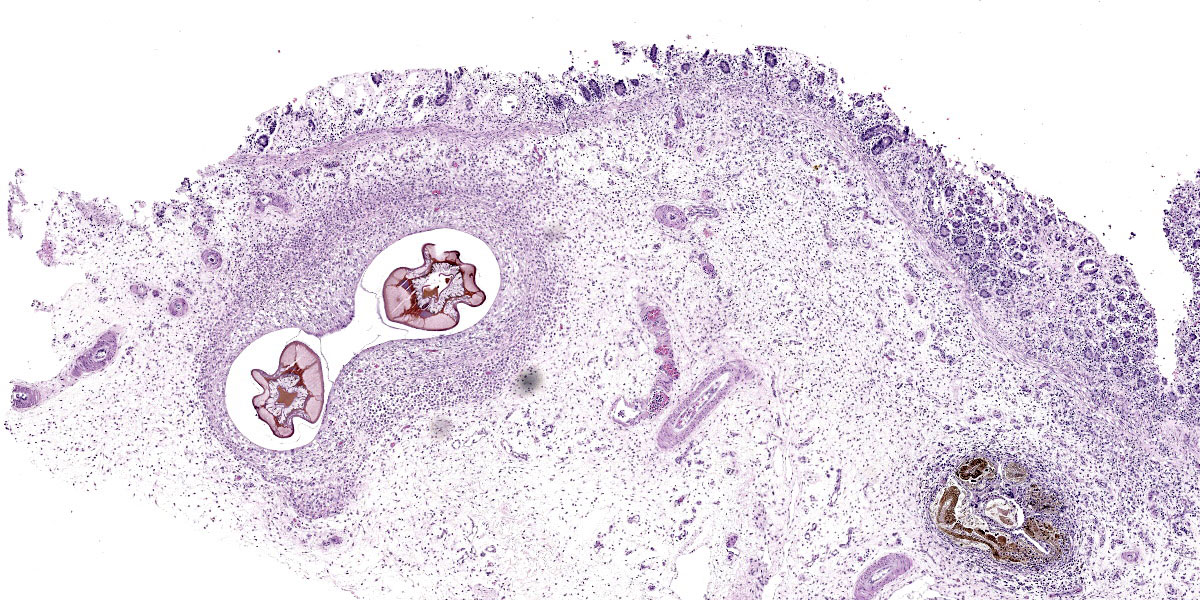

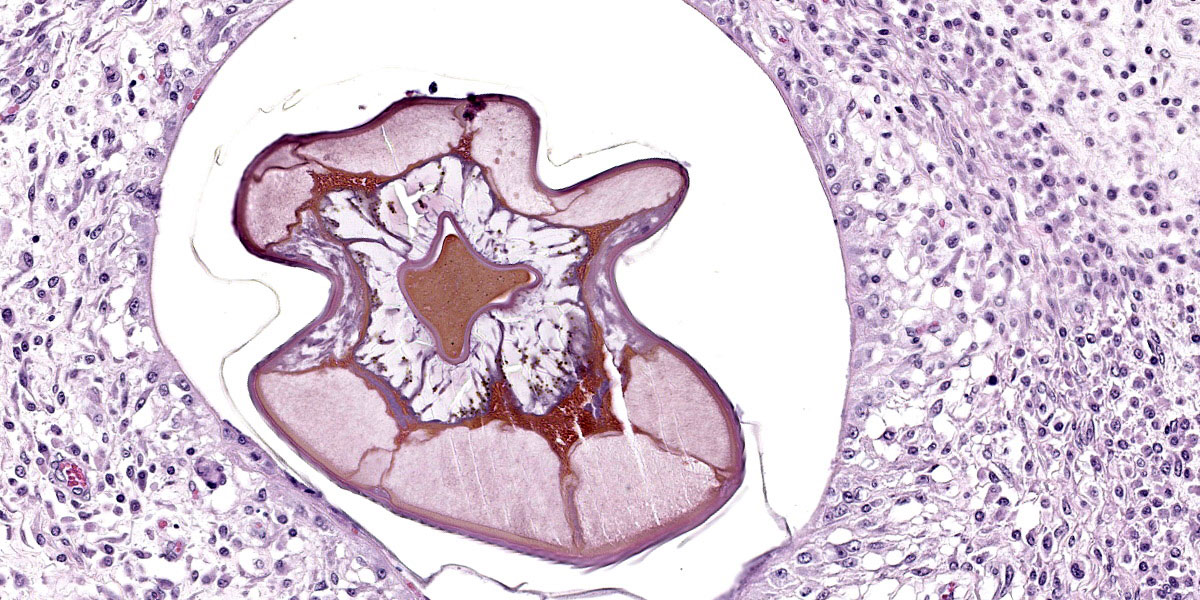

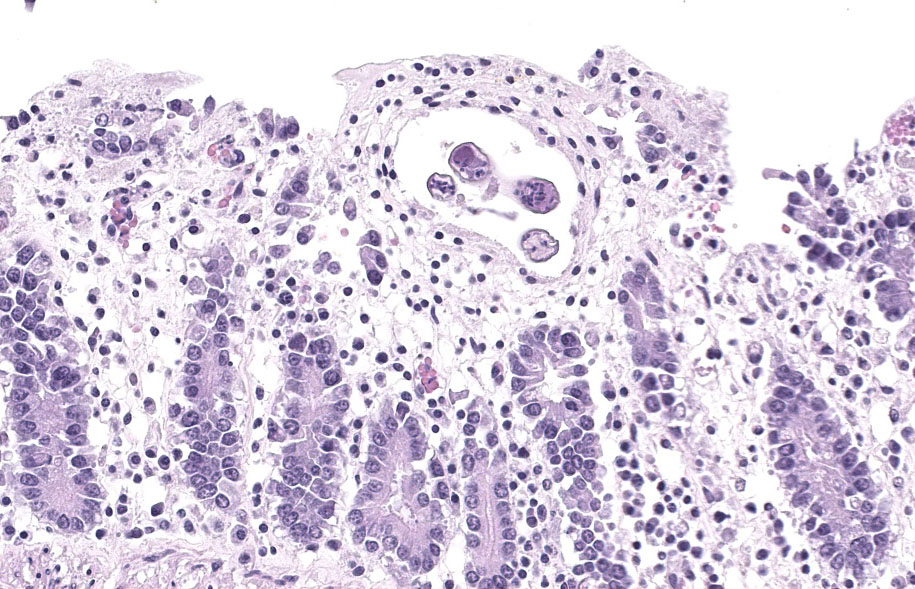

Randomly distributed throughout the large intestinal submucosa and rarely within the mucosa, there are encapsulated 20-400 µm diameter larval nematodes. The nematodes have a ridged eosinophilic cuticle, platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, vacuolated lateral cords, and an intestine that is lined by few multinucleated cells and contains red to brown granular material. Occasional nematodes are mineralized. The nematodes are often surrounded by a moderate number of macrophages and few fibroblasts. The submucosa is markedly edematous and contains a low number of lymphocytes and fewer plasma cells. The lamina propria contains a low to moderate number of plasma

cells, including occasional Mott cells, fewer lymphocytes and occasional macrophages and neutrophils. There are rare small superficial mucosal erosions.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Colon: Colitis, granulomatous, chronic, with edema and intralesional encapsulated nematodes consistent with small strongyles.

Contributor’s Comment:

Referred to as small strongyles or red worms, the more than 50 species of cyathostomins can infect horses of any age, but more severe clinical disease is typically noted in young horses.2 Cyathostomins have a direct life cycle and horses become infected with cyathostomins by ingestion of the early L3 stage, which burrows into the mucosa of the hindgut and forms a fibrous capsule within

two weeks, cloaking it from the host’s immune system.2,4 Development can arrest for as long as 2 years in the early L3 stage.2

Late fourth stage larvae exit the mucosa to mature to the adult stage in the intestinal lumen.4 The emergence of a large number of L4 larvae from the hindgut, in late winter and early spring in temperate regions and late summer and early fall in tropical regions, triggers the syndrome of larval cyathostomiasis.3 Clinically, horses present with rapid weight loss, colic, leukocytosis, hyperglobulinemia, hypoproteinemia, rough hair coat, and severe diarrhea containing a large number of larval cyathostomins detectable by dilution of feces with water and viewing under a microscope.3,4 Edema of the limbs and ventrum can also be seen.3

Contributing Institution:

University of Florida

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Infectious Diseases and Pathology

Gainesville, FL 32611-0880

http://idp.vetmed.ufl.edu/

JPC Diagnosis:

Colon: Colitis, granulomatous, multifocal, mild to moderate, with marked submucosal edema and small strongyle larvae.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor notes, there are approximately 40-50 species of cyathostomins that parasitize the cecum and colon of horses, and as many as 15 to 20 of these species commonly colonize the same host at the same time.1 Luckily, cyathostomin larvae do not migrate far beyond the mucous membranes of the cecum and colon and feed mainly on intestinal contents, so their pathogenic effect can be minimal.1,5 However, infection by large numbers of arrested cyathostomin larvae and their simultaneous emergence from the gut wall can cause the clinical disease of larval cyathostominosis described by the contributor.

Larval cyathostominosis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in horses and can affect horses of any age.5 Grossly, theco lonic mucosa is studded with 2-5 mm diameter nodules that are slightly raised, red or black, and contain encysted third or fourth stage hypobiotic (developmentally arrested) larval nematodes.5 Histologically, the mucosa and submucosa are edematous, as in this case, and may contain a mixed inflammatory response either centered on encysted larvae in the submucosa or more diffusely throughout the lamina propria.5

Cyathostomins are widespread throughout the world, and even apparently healthy horses may be infected with tens to hundreds of thousands of their larvae. As anthelmintic resistance of cyathostomins is a large and growing problem, many current preventive measures are focused on pasture and herd management solutions.1 It has been said (by a parasitologist, naturally) that “the king’s horses probably had fewer worms” owing to the immediate removal of fecal material after deposition, and this concept has inspired the development of pasture vacuums and pasture sweepers.1 Other suggested preventive measures include rotation of administered anthelmintics, orchestrating field plowing to reduce the spreading of infective fecal material, and the composting of horse manure.1

Conference discussion focused initially on tissue identification. The significant amount of autolysis in section complicated the issue, but the lack of identifiable villi placed this solidly in the colon. The examined section was notable for the lack of fibrosis around the larvae, leading conference participants to speculate that this tissue section was procured early in infection or that the horse’s immune response to the larvae might have been impaired. Participants also discussed how simultaneous eruption of myriad larvae can cause loss of the enteric mucosal barrier, providing fertile soil for the development of a potentially profound enterotoxemia.

References:

- Bowman, DD. Helminths. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th ed. Elsevier;2009:92-94.

- Corning S. Equine Cyathostomins: A review of biology, clinical significant and therapy. Parasites and Vectors. 2009; 2(S2): S1.

- Peregrine AS, McEwen B, Bienzle D, Koch TG, Weese JS. Larval cyathostominosis in horses in Ontario: an emerging disease? Can Vet J. 2006;47(1):80-82.

- Sellon DC, Long MT. Strongylosis. In: Sellon DC, Long MT, eds. Equine Infectious Diseases. Saunders; 2007:480-486.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier;2016:216.