Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

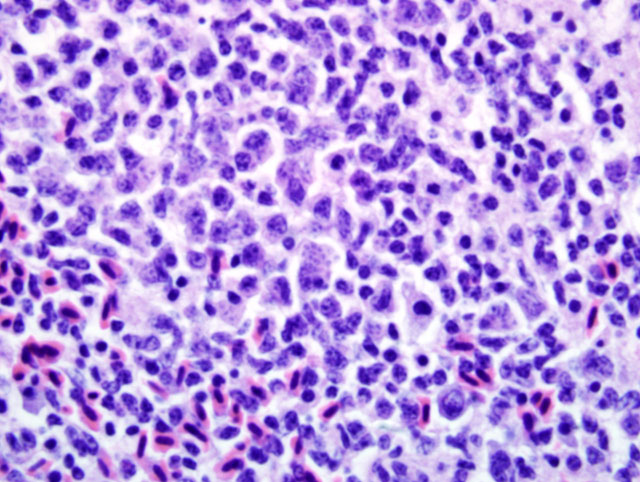

Liver: Infiltrating and partially effacing the peri-portal hepatocytes is a mild to moderate mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphoblasts with fewer histiocytes and plasma cells. The cytoplasm of scattered lymphoblasts contain 1-5, small, oval, 1-2μm diameter basophilic organisms within a thin, clear, well demarcated parasitophorous vacuole. Rarely these organisms peripheralize and indent the nucleus of the infected cells. Small numbers of the basophilic organisms are free amongst the inflammatory infiltrate. Small aggregates of the lymphoblasts are scattered within the sinusoids.Â

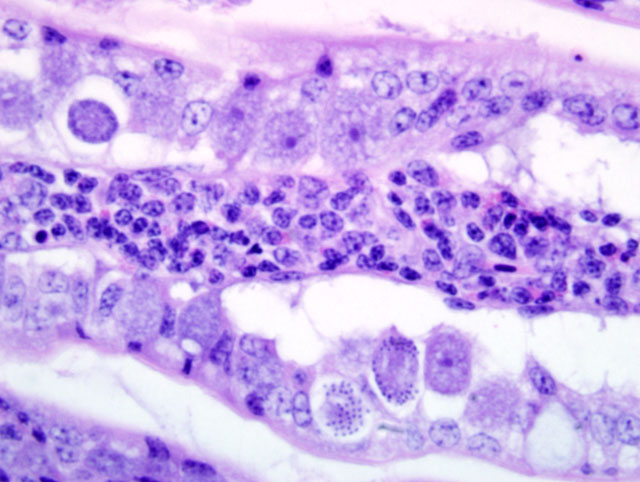

Spleen (not in every section): Diffusely the peri-arteriolar lymphoid sheaths are moderately expanded with variable numbers of small, oval, 1-2μm diameter basophilic organisms with a thin, clear, well demarcated parasitophorous vacuole within the cytoplasm of occasional lymphocytes (Fig. 3-2). Rarely these organisms are present in the sinusoidal histiocytes.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Diffuse, severe, chronic, lymphoplasmacytic, histiocytic and eosinophilic enteritis with intraepithelial coccidian parasites.

Liver: Moderate, diffuse, lymphocytic peri-portal hepatitis with intralesional merozoites consistent with Atoxoplasma spp.Â

Spleen: Moderate lymphoid hyperplasia with intralesional merozoites consistent with Atoxoplasma spp.Â

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Other potential causes of lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphoma in avian species include Mareks disease virus, an alpha-herpesvirus, and Avian leucosis virus, a retrovirus, which can cause lymphoma-like lesions in multiple organs in chickens and many avian species respectively. As the immunohistochemistry results were overwhelmingly positive for CD3, a T cell antigen, a retroviral-induced lesion was determined to be less likely as these viruses typically induce B-cell proliferation. Transmission electron microscopy was performed on the inflammatory infiltrate to rule out viral induced lymphoma. No viral particles were identified in the examined tissues; Atoxoplasma merozoites were not evaluated.

Atoxoplasma spp are host specific apicomplexian parasites that are infective to birds within the family Passeriformes. This is a large family encompassing many different species of birds. Within this family it is the finches, sparrows, thrushes and other small songbirds that are most commonly reported to be affected by this parasite. In the wild these parasites are endemic in low levels (3, 14) however it is likely that the levels are underestimated due to the difficulty in identifying the circulating merozoites.(5,7,8) Atoxoplasma has become a major cause of mortality in zoos and research facilities that utilize wild caught colonies of passeriform birds.(5,6) The stress from being in captivity and poor sanitary conditions have been identified as contributing causes for the high morbidity in these facilities.(6,7,12) Interestingly Atoxoplasma has been reported in raptors.(10) However, as so few cases exist, the significance of the parasite outside of the passerine birds is unknown.Â

Affected birds will exhibit a loss of appetite with subsequent weight loss and reduction of the pectoral musculature, which is termed going light. The animal can become depressed, have ruffled feathers, a distended abdomen, and develop diarrhea, dehydration and a loss of balance.(2,11) Subclinically infected birds will show no outward signs of infection but will shed infective oocysts into the environment. In infected colonies morbidity can approach 100% with a significant mortality rate. Grossly, there are varying degrees of pectoral musculature atrophy, coelomic adipose depletion and enteritis.

Since the discovery of this parasite there has been considerable debate as to how it should be classified. In 1950 Garnham proposed the name Atoxoplasma (12) as it was felt this name addressed the fact that the parasite resembled Toxoplasma but was not Toxoplasma. Since that time it was determined that these parasites belong to the family Eimeriidae and closely resemble Isospora spp. Both Atoxoplasma and Isospora oocysts contain two sporocysts each containing four sporozoites. Both parasites follow the basic coccidian life cycle where the sporozoites will excyst in the intestinal tract and invade the enterocytes, undergo merogony, develop into microgamonts or macrogamonts within the enterocytes and undergo sexual reproduction to form unsporulated oocysts. The oocysts are passed in the feces and sporulate in the environment where they will be ingested by the next host.Â

Atoxoplasma spp differ from Isospora spp during merogony. After ingestion of the Atoxoplasma oocysts the sporozoites and merozoites can directly infect mononuclear cells that have been recruited into the intestine in response to the coccidian parasites.(1,7,9,11,12) The merozoites enter into the circulation where they continue to undergo merogony within the mononuclear inflammatory cells. Through a currently unknown mechanism this parasite initiates a marked lymphoproliferative response. Peri-vascular accumulations of mononuclear inflammatory cells develop systemically and often contain intracytoplasmic merozoites. Depending on the severity of the infection the inflammatory infiltrates can resemble mild lymphohistiocytic inflammatory response to widespread lymphoma.Â

As previously mentioned the Atoxoplasma merozoites were not evaluated under the electron microscope. The reported ultrastructural characteristics of this parasite include a pellicle consisting of an outer plasma membrane and an inner complex of two membranes, subpellicular microtubules, a conoid, rhoptries, micronemes, mitochondria, and a micropore all within a parasitophorous vacuole.(2,9,11)

In summary, when evaluating tissue from a passerine bird and a coccidial infection with severe lymphoproliferative lesions, Atoxoplasma should be high on the differential list. Close evaluation of the lymphocytic infiltrates for intracellular merozoites is warranted in these cases.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Small intestine: Enteritis, lymphoblastic, transmural, diffuse, severe, with crypt loss, intraleukocytic apicomplexan merozoites, and intra-epithelial gamonts and schizonts.

2. Liver: Hepatitis, portal, lymphoblastic, diffuse, marked, with intracytoplasmic apicomplexan merozoites.

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Ball SJ, Brown MA, Daszak P, Pittilo RM: Atoxoplasma (Apicomplexa: Eimeriorina: Atoxoplasmatidae) in the Greenfinch (Carduelis chloris). J Parasitol 84:813-817, 1998

3. Bennett GF, Garvin M, Bates M.: Avian hematozoa from west-central Bolivia. J Parasitol 77:207-211, 1991

4. Fadly AM, Payne LN: Leukosis/sarcoma group. In: Disease of Poultry, ed. Saif YM, Barnes HJ, Glisson JR, Fadly AM, McDouglad LR, Swayne DE, 11th ed., pp. 465-516. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 2003

5. Giacoma R, Stefania P, Ennio T, Giorgina VC, Giovanni B, Giacomo R: Mortality in Black Siskins (Carduelis atrata). J Wildlife Dis 33:152-157, 1997

6. McAloose D, Keener L, Schrenzel M, Rideout B: Atoxoplasmosis: Beyond Bali Mynahs. Proc. Am. Assoc. Zoo Vet pp. 64-67, 2001

7. McNamee P, Pennycott T, McConnell S: Clinical and pathological changes associated with atoxoplasma in a captive bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula). Vet Rec 136:221-222, 1995

8. Middleton AL: Lymphoproliferative disease in the American Goldfinch, Carduelis tristis. J Wildlife Dis 19:280-285, 1983

9. Quiroga MI, Aleman N, Vazquez S, Nieto JM: Diagnosis of Atoxoplasmosis in a Canary (Serinus canaries) by histopathologic and ultrastructural examination. Avian Dis 44:465-469, 2000

10. Remple JD: Intracellular hematozoa of raptors: A review and update. J Avian Med Surg 18:75-88, 2004

11. Sanchez-Cordon PJ, Gomez-Villamandos JC, Guierrez J, Sierra MA, Pedrera M, Bautista MJ: Atoxoplasma spp. infection in captive canaries (Serinus canaria). J Vet Med A 54:23-26, 2007

12. Schrenzel MD, Maalouf GA, Gaffney PM, Tokarz D, Keener LL, McClure D, Griffey S, McAloose D, Rideout BA: Molecular characterization of Isosporoid coccidia (Isospora and Atoxoplasma spp.) in passerine birds. J Parasitol 91:635-647, 2005

13. Swayne DE, Getzy D, Siemons RD, Bocetti C, Kramer L: Coccidiosis as a cause of transmural lymphocytic enteritis and mortality in captive Nashville Warblers (Vermivora ruficapilla). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 27:615-620, 1991

14. van Riper III C, van Riper S: Discovery of Atoxoplasma in Hawaii. J Parasitol 73:1071-1073, 1987

15. Witter RL, Schat KA: Mareks disease. In: Disease of Poultry, eds. Saif YM, Barnes HJ, Glisson JR, Fadly AM, McDouglad LR, Swayne DE, 11th ed., pp. 407-449. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 2003