Signalment:

16-year-old pony breed mare (

Equus caballus).The pony became ataxic one week before presenting at the clinic. The referring veterinarian found

neurological signs affecting the tail and hindlimbs. At the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science clinic,

neurological examination indicated that facial nerves (V and VII) were affected. Muscle tone in the tail and anus

was reduced. Hindquarter skin had areas of hypersensitivty and areas of reduced sensitivity. Severe ataxia was

found.

Gross Description:

In the gluteal region there was edema and hemorrhages centered on nerves. The lumbosacral

spinal cord (L5-S1) was firm and slightly irregular in thickness. There was hemorrhage in the epidural and subdural

spaces and dark hemorrhagic foci in the spinal cord.

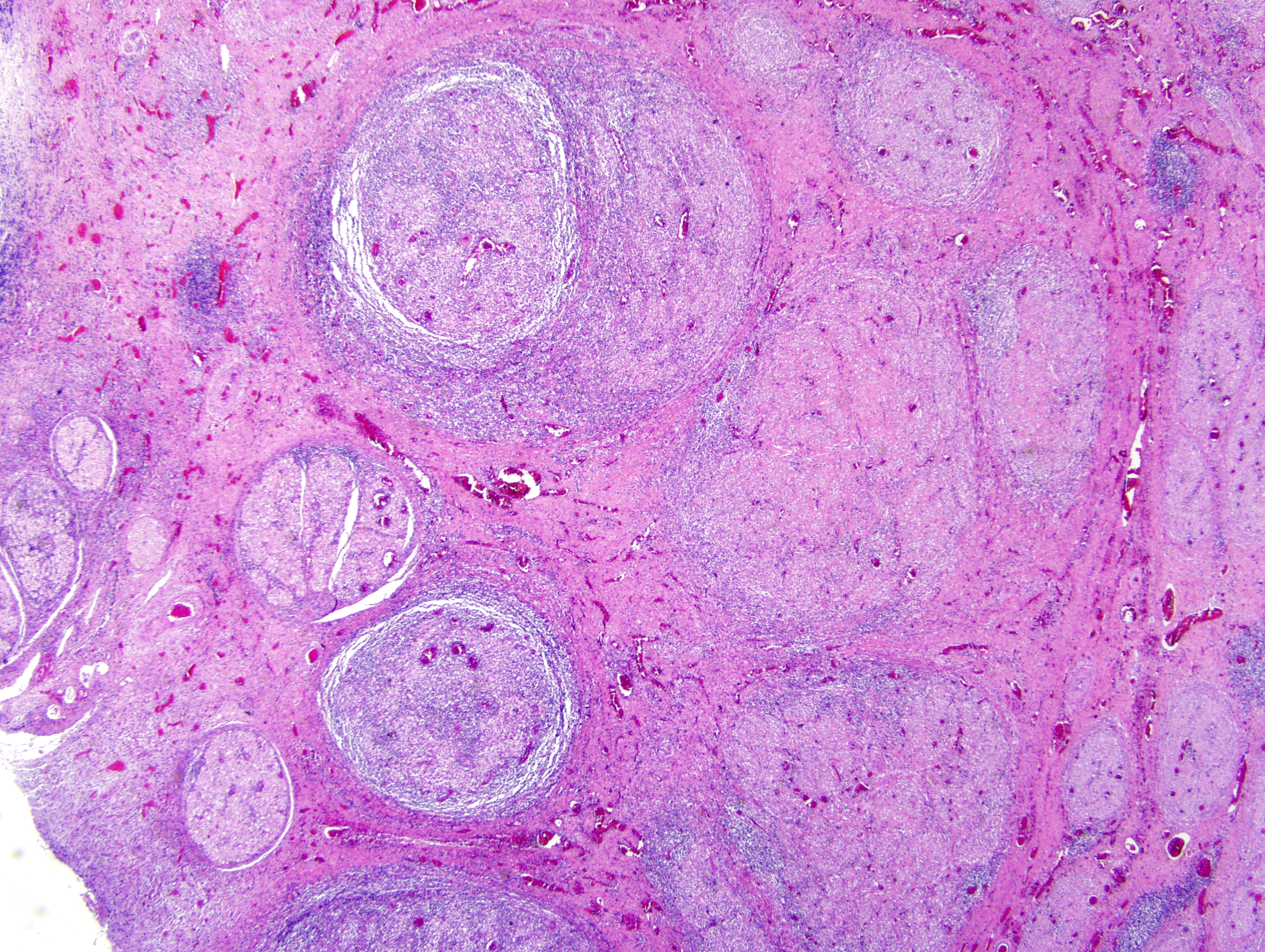

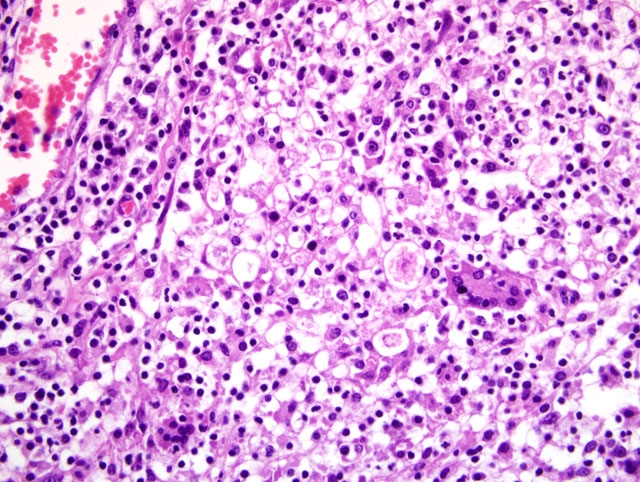

Histopathologic Description:

Cauda equina: Nerves, extradural and intradural, are moderately to severely

infiltrated by lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid macrophages and fewer multinucleated giant cells. There is

axonal degeneration and loss within the affected nerves. The nerve fibers are embedded in a collagen rich fibrous

tissue (fibrosis) with a moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and focally extensive hemorrhages. Fibroplasia is

also seen within nerves. Dorsal root ganglia (not present in all sections) have a moderate to severe

lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and show axonal degeneration and loss as well as rare hypereosinophilic shrunken

neurons (neuronal necrosis). Several cranial nerves and nerves associated with hemorrhages in the gluteal region

had moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (tissue not submitted).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cauda equina: Neuritis and perineuritis, granulomatous, multifocal to

diffuse with epineurial and perineurial fibrosis.

Condition:

Cauda equina syndrome

Contributor Comment:

Neuritis of the cauda equina, or polyneuritis equi, is a nonsuppurative inflammation

mainly affecting the nerve trunks of the cauda equina in horses.(2) Clinically the disease is characterized by

paralysis of the tail, reduced muscle tone of the anus and rectum, paralysis of the bladder (sometimes with urinary

incontinence), paresthesia or anesthesia of the tail and perineum, and incoordination of the hindlimbs. There may

also be involvement of cranial nerves.(2) Lesions are reported to be most severe in the sacral and coccygeal nerves,

and are characterized by granulomatous inflammation, hemorrhage and fibrosis causing irregular thickening and

discoloration of the nerve roots. The inflammation is usually more severe in the extradural parts of the nerves

compared to the intradural nerve segments. Although more mildly, nerves outside the cauda equina, including

cranial nerves, are commonly also affected.(2) In the present case, nerve associated hemorrhagic lesions were

grossly visible in the gluteal region. A recent case report described biopsy of tail musculature as an aid in the

antemortem diagnosis of polyneuritis equi.(1) The cause is unknown, but the morphology of the lesion suggests that

it is an immune-mediated disorder.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Spinal cord, cauda equina: Polyradiculoneuritis, granulomatous, multifocally extensive, marked,

with perineural and epineural fibrosis and nerve fiber loss.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a succinct overview of this perplexing entity. Many favor the

term polyneuritis equi (PNE) over

neuritis of the cauda equina or

cauda equina syndrome because it more

accurately reflects the typical widespread distribution of inflammation affecting not only the cauda equina, but often

spinal roots and cranial nerves as well.(3) As alluded to by the contributor, while the pathogenesis of the lesion

remains obscure, Adenovirus I has been isolated from horses with PNE, and it is hypothesized that a viral infection

may incite an autoimmune polyradiculoneuritis in horses with this condition.(3)

Halicephalobus gingivalus has

been reported as a cause in one case of PNE.(2)

Whatever the inciting etiology, an immune-mediated mechanism is suggested by similarities with Guillain-Barre

syndrome (GBS) in humans and experimental allergic neuritis (EAN) in laboratory animals. Specifically, PNE,

GBS and EAN are all characterized by demyelination in the proximal roots with invading mononuclear cells and

macrophages stripping away segments of the myelin sheath. Furthermore, circulating antibodies to the P2 myelin

protein, the antigen that upon injection into laboratory animals produces EAN, have been demonstrated in horses

with PNE. Nevertheless, the role of these antibodies in the pathogenesis of PNE is unknown; they may be causal or

arise secondary to demyelination and inflammation.(3)

As mentioned by the contributor, a recent case report describes biopsy of the sacrocaudalis dorsalis lateralis muscle,

the innervation of which arises in the cauda equina, for the antemortem diagnosis of PNE. In frozen biopsy

specimens, intense lymphohistiocytic inflammation infiltrated and effaced terminal intramuscular nerve branches

while sparing the myofibers, which exhibited angular atrophy of both muscle fiber types (neurogenic atrophy) and

occasional hypertrophic or split fibers.(1)

References:

1. Aleman M, Katzman SA, Vaughan B, Hodges J, Crabbs TA, Christopher MM, Shelton GD, Higgins RJ:

Antemortem diagnosis of polyneuritis equi. J Vet Intern Med

23:665-668, 2009

2. Maxie MG, Youssef S: Nervous system.

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed.

Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, p. 444. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

3. Summers BA, Cummings JF, De Lahunta A: Veterinary Neuropathology, pp. 433-434. Mosby, St. Louis, MO,

1995