Signalment:

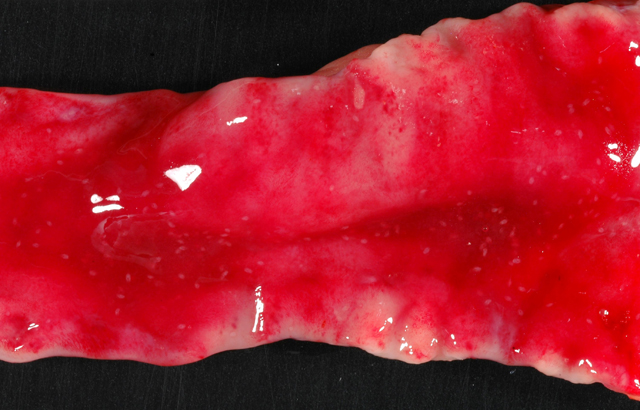

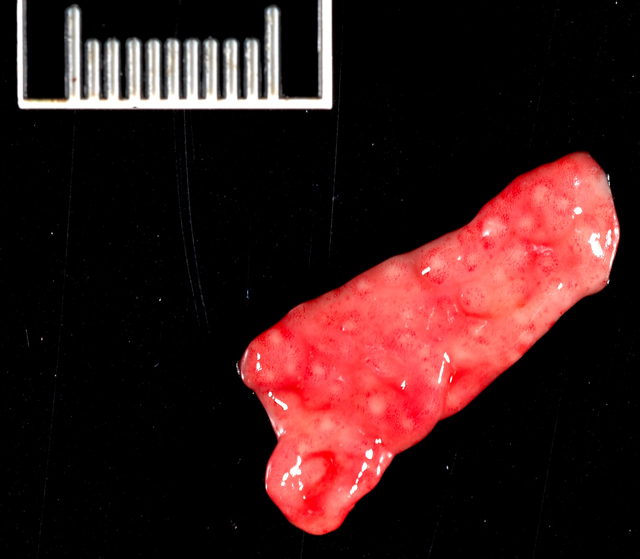

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

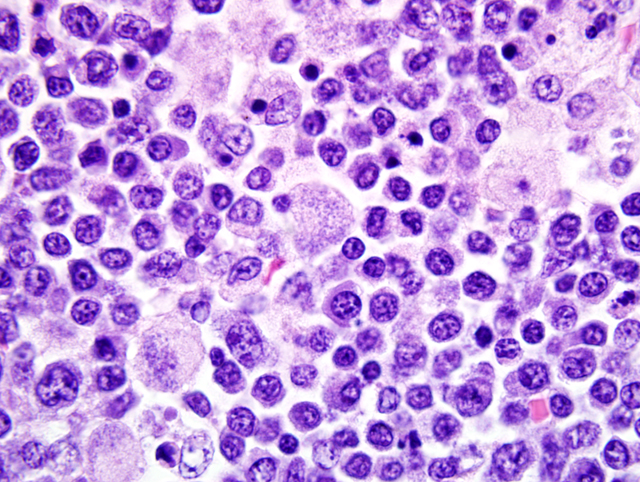

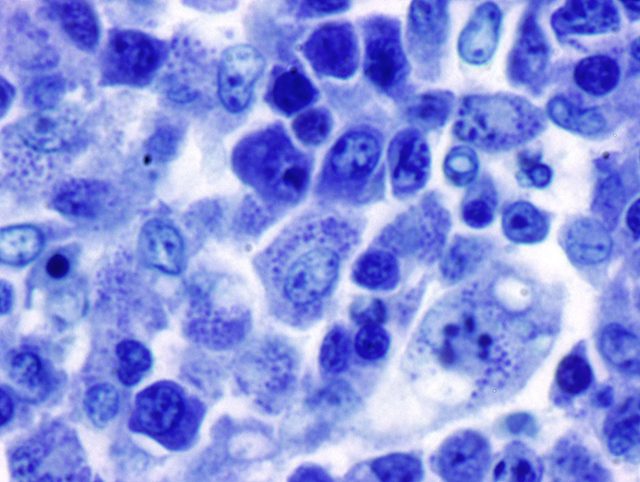

Mesenteric lymph node: In this lymph node, follicles are absent and subcapsular and medullary sinuses are filled with numerous macrophages that have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and frequently contain numerous basophilic, less than1 um diameter, coccoid to coccobacillary organisms surrounded by a thin clear space or occasionally forming clusters within vacuoles. Smaller numbers of macrophages are scattered through the cortex, where there are multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis. Increased numbers of plasma cells are present throughout the cortex and medullary cords.Â

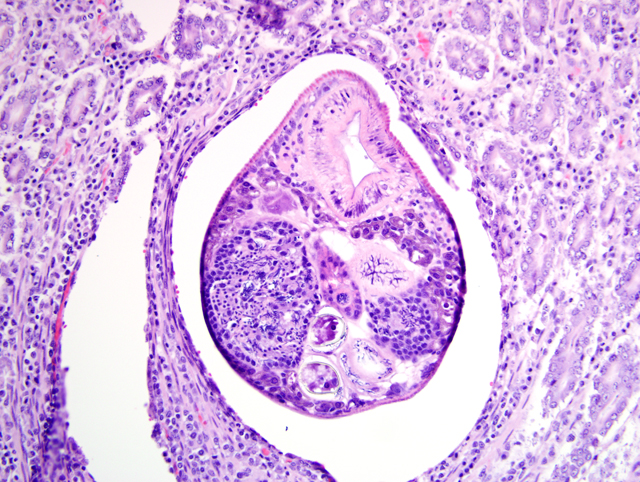

Duodenum: In this section of duodenum, there is generalized villous blunting with multifocal, epithelial necrosis and accumulation of sloughed cells within crypts (crypt abscesses). Embedded within the mucosa as well as within the intestinal lumen are multiple profiles of acoelomic parasites with a spiny cuticle, suckers, and operculated eggs. Some sections of individual parasites have both spermatids and ova (hermaphroditic). Moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells with fewer macrophages infiltrate the lamina propria and form a nearly circumferential band between the muscularis mucosa and the base of villi. Macrophages containing clusters of the same intracellular organisms observed in the lymph node (described above) are occasionally noted within the muscularis mucosa and submucosa. Mucosal epithelium is alternately attenuated to regenerative with some cells exhibiting large, vesicular nuclei. There are scattered regions of submucosal hemorrhage.

Special stains: The organisms seen within macrophages on H&E stained red (gram-negative) with Brown and Brenn and purple-blue with Giemsa stains. Machiavellos stain was inconclusive.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Mesenteric lymph node: Severe, multifocal to coalescing granulomatous and necrotizing lymphadenitis with intracellular rickettsiae (Neorickettsia helmintheoca, presumptive).

2. Duodenum: Moderate, multifocal, chronic, granulomatous enteritis with intracellular rickettsiae.

3. Duodenum: Trematodiasis (Nanophyetus salmincola).

4. Duodenum: Moderate, diffuse, chronic, lymphoplasmacytic enteritis.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Salmon poisoning disease generally has an incubation period of 5-7 days and common clinical signs are fever, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, and lymphadenopathy.(3) Bloody diarrhea and hypothermia may develop in the late stages of the disease, as was the case in this dog. The presence of the fluke is generally of little clinical significance.(3) If left untreated, the disease has a high mortality rate; the specific cause of death is unknown. Neorickettsia are able to evade the immune system by inhibition of lysosomal fusion with its parasitophorous vacuole, a process which has been shown to be reversed by oxytetracycline treatment.(9) Accordingly, appropriate treatment of the disease warrants an excellent prognosis. In one study, 91% of naturally infected dogs treated with tetracycline made a full recovery.(8) Recovered animals generally develop immunity.3

Antemortem diagnosis is based on history and typical clinical signs along with presence of N. salmincola ova on fecal flotation.(8) Further confirmation is provided by lymph node aspirates showing macrophages with rickettsia-like cytoplasmic inclusions. The organisms stain purple with Giemsa, red with Macchiavellos, black or dark brown with Levaditis method, and pale blue with hematoxylin and eosin. Peripheral lymphadenopathy was not present in this case. On necropsy, gross lesions typically involve the lymphoid tissues, spleen, and gastrointestinal tract. These include lymphoid tissue enlargement, lymph node petechiation, splenomegaly, and petechiation and ulceration in the gastrointestinal tract.(3) Similar gross findings were noted in the present case, with the addition of gross thickening of the duodenum and pinpoint raised mucosal nodules in the stomach, duodenum, and colon, which corresponded histologically to lymphoid follicles and inflammatory nodules in which there were macrophages with intracellular rickettsiae. The presence of the rickettsiae in macrophages within the stomach wall has not been reported. Given that N. helminthoeca is presumed to be inoculated into the intestinal mucosa, its presence in the stomach suggests either inoculation in gastric mucosa as well, or a particular affinity for this tissue during systemic distribution. Diagnosis in this case was facilitated by the finding of classic microscopic lesions. In the lymphoid tissues, these are depletion of mature lymphocytes, foci of necrosis, and hyperplasia of mononuclear phagocytes with intracytoplasmic rickettsia-like organisms. Trematodes are found embedded in the intestinal mucosa, primarily in the duodenum, as was the case here. Nonsuppurative meningitis or meningoencephalitis has been reported experimentally, but neither was observed in this case.4

The endemic area of O. silicula, the first intermediate host of the trematode, ranges from southern Vancouver Island as far south as Lake Tahoe along the western slopes of the Cascade and Sierra mountains.(7) The natural habitat of the snail used to define the affected area, but stocking of sport fisheries and other public waters with infected fish from both state and private hatcheries, as well as natural movement of salmonid fish to new areas, has expanded the range of infected fish, thereby expanding the range of potential cases of salmon poisoning disease.(7) In the present case, further questioning of the owner revealed that the family had eaten trout from a region in the Sierra foothills southwest of Lake Tahoe, which could represent the source of exposure for this dog. Interestingly, salmon poisoning or a similar disease could be emerging in an entirely separate region. There are reports from southern Brazil of a disease in dogs with gross and histopathologic lesions similar to salmon poisoning disease.(6) In these cases, intracytoplasmic organisms were observed, and trematodes were present in the large intestine of one dog that were considered consistent with Ascocotyle arnaldoi, a trematode that also requires both a snail and fish intermediate host. Preliminary PCR studies have isolated gene fragments with close homology to N. helmintheoca from tissues of two such affected dogs.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Duodenum: Enteritis, lymphohistiocytic and plasmacytic, diffuse, moderate, with villar blunting and fusion, crypt hyperplasia and abscesses, fibrinous vasculitis, hemorrhage, and numerous intrahistiocytic rickettsiae.Â

2. Duodenum: Intramucosal adult trematode.

3. Lymph node, mesenteric (per contributor): Lymphadenitis, necrotizing and histiocytic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with plasmacytosis, and numerous intrahistiocytic rickettsiae.

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Gai JJ, Marks SL: Salmon poisoning disease in two Malayan sun bears. J Am Vet Med Assoc 232(4):586-588, 2008

3. Gorham JR, Foreyt WJ: Salmon poisoning disease. In: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, ed. Greene CE, 3rd ed. pp. 198-203. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2006

4. Hadlow WJ: Neuropathology of experimental salmon poisoning of dogs. Am J Vet Res 18(69):898-908, 1957

5. Headley SA, Scorpio D, Barat N, Vidotto O, Dumler JS: Neorickettsia helminthoeca in dog, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 12(8):1303-1305, 2006

6. Headley SA, Vidotto O, Scorpio D, Dumler JS, Mankowski J: Suspected cases of Neorickettsia-like organisms in Brazilian dogs. Ann NY Acad Sci 1026:79-83, 2004

7. Hedrick RP, Amandi A, Manzer D: Nanophyetus salmincola: the trematode vector of Neorickettsia helminthoeca. Calif Vet 44:18-22, 1990

8. Mack RE, Bercovitch MG, Ling GV, Lobingier RT, Melli AC: Salmon poisoning disease complex in dogs a review of 45 cases. Calif Vet 44:42-45,1990

9. Rikihisa Y: Mechanisms to create a safe haven by members of the family Anaplasmataceae. Ann NY Acad Sci 990:548-55, 2003