Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 23

24 April, 2019

CASE IV: UMC172 (JPC 4099791)

Signalment: 21 year old Thoroughbred gelding (Equus caballus)

History: This 21 year old Thoroughbred gelding was euthanized and submitted for necropsy due to a severe, chronic, non-healing wound on its right hind leg.

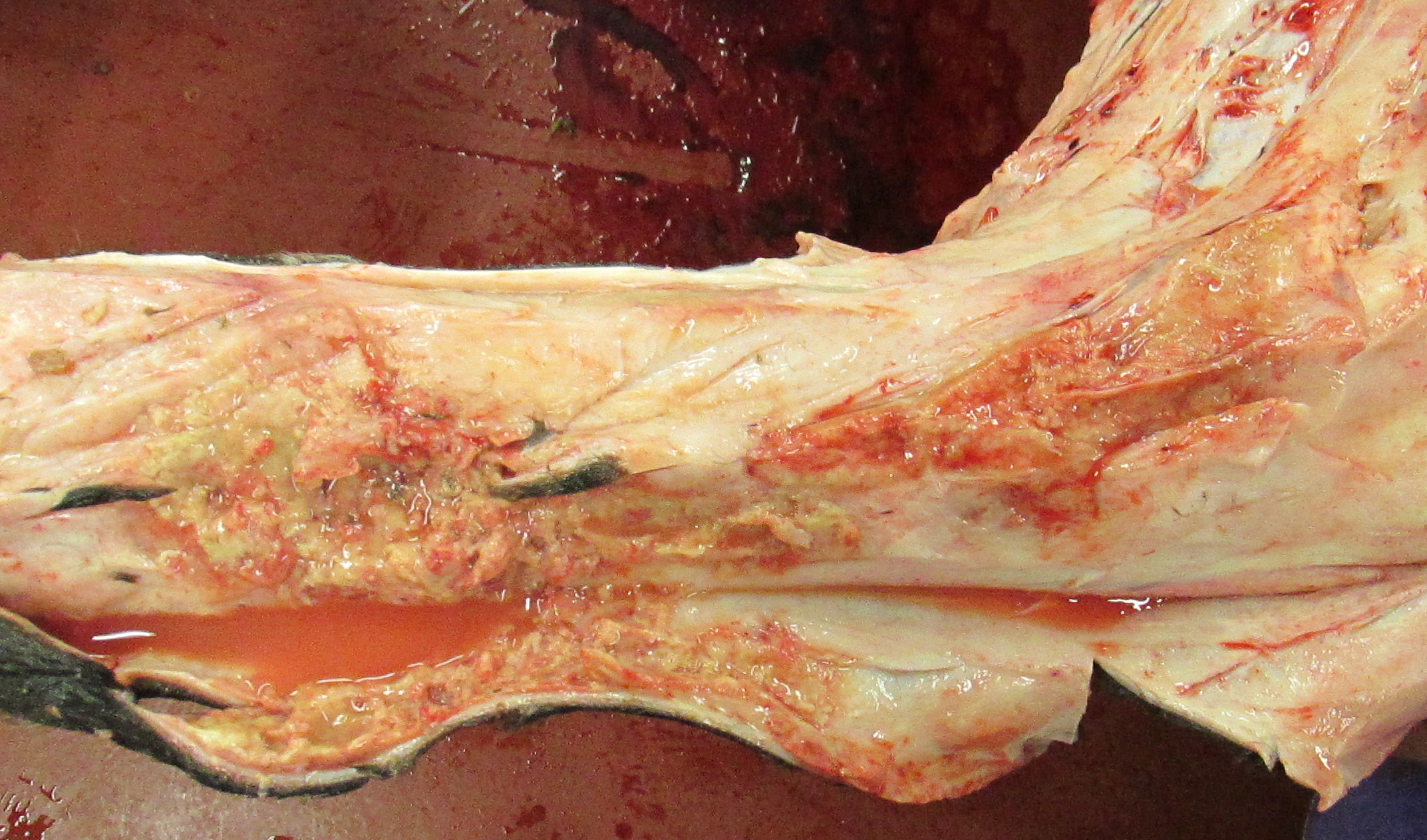

Gross Pathology: A 530kg body weight, aged adult, bay gelding, in moderate body condition (4/9 body condition score) is necropsied. The medial right hind limb is diffusely swollen from the inguinal region down to the level of the fetlock. A punctate fistula is noted on the medially, slightly below the fetlock joint. Considerable dense fibrous tissue is evident in the subcutis of the tibia and metatarsals. Roughly 100 ml watery translucent yellow orange fluid pools in the subcutis during dissection. Extending from the medial hock to the medial fetlock is soft, tan, friable tissue that oozes fluid. The process does not affect the bone, itself tendon sheaths or the joint fluids of the hock, fetlock or pastern. Other gross lesions include ulcers in the squamous portion of the stomach, and a large free-floating abdominal blood clot, thought to be a result of trauma sustained during euthanasia. The abnormalities in the organs submitted to the conference were unexpected.

Laboratory results: NA

Microscopic Description:

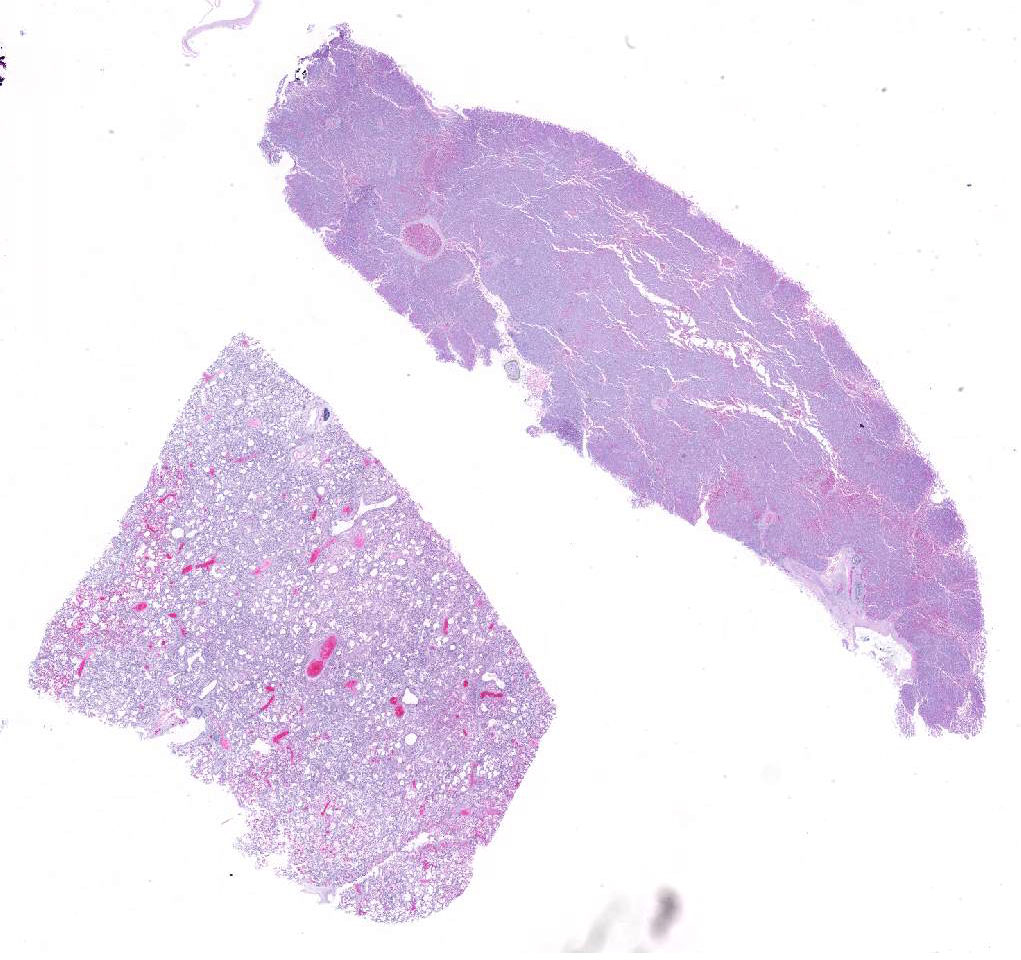

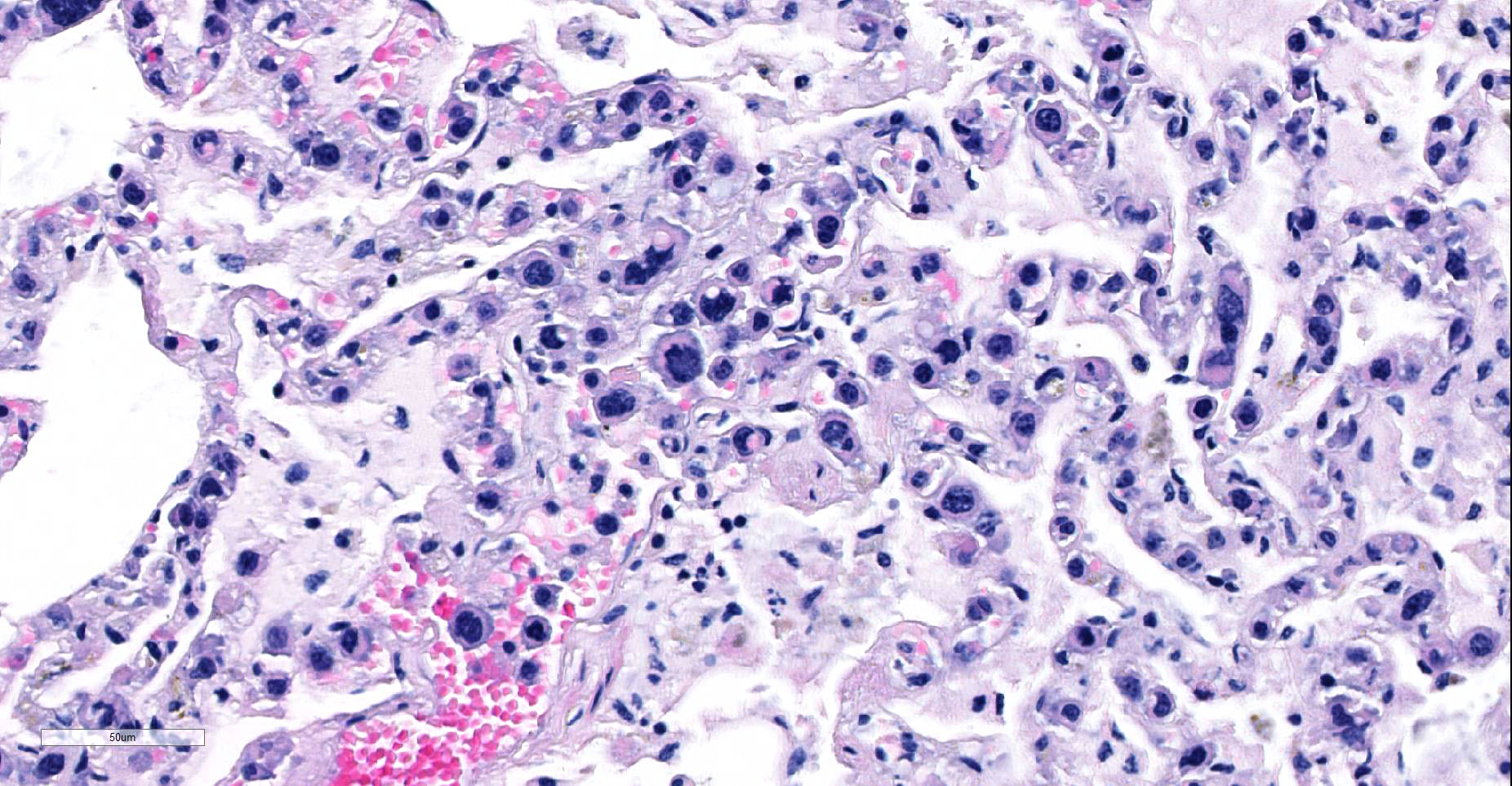

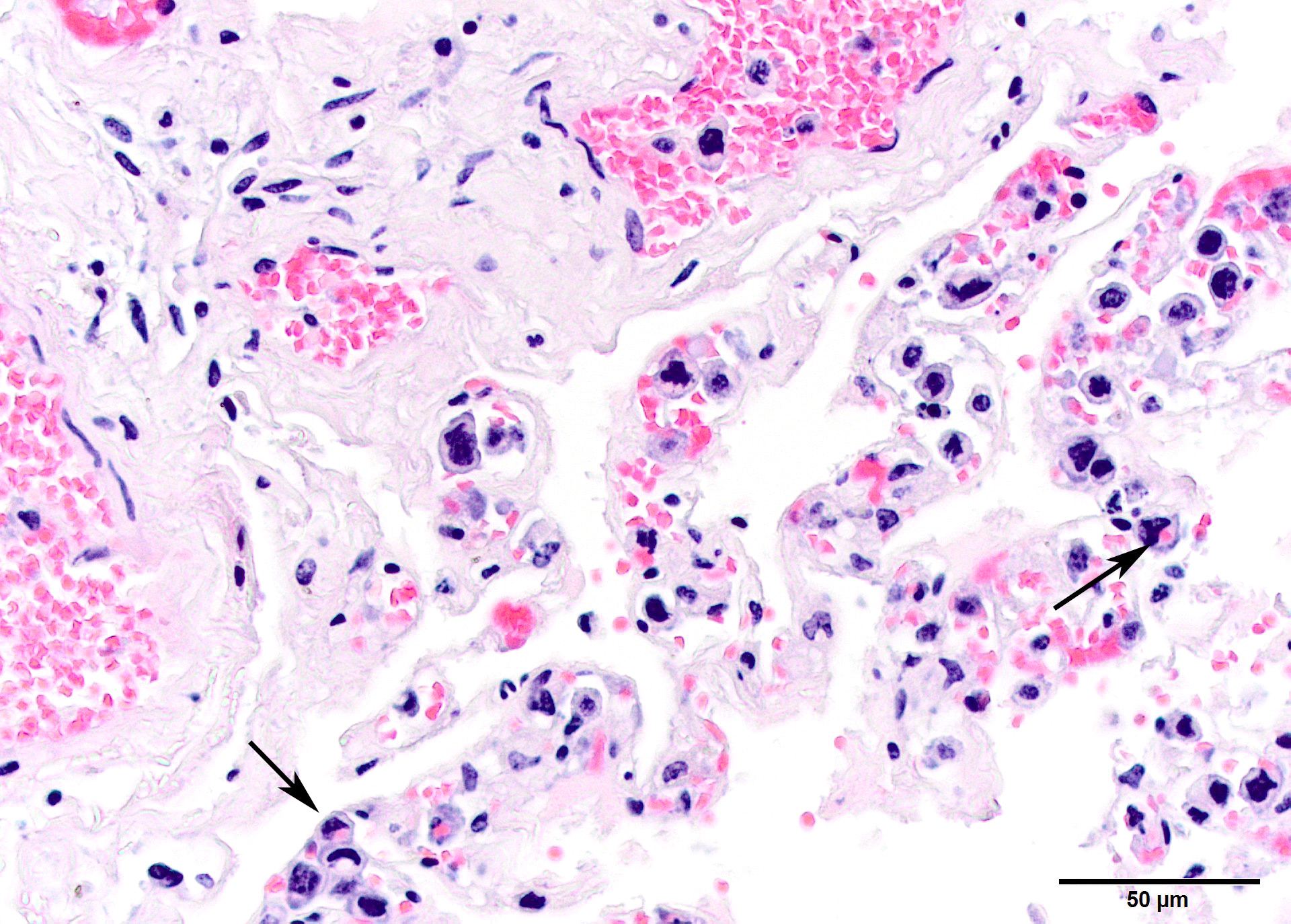

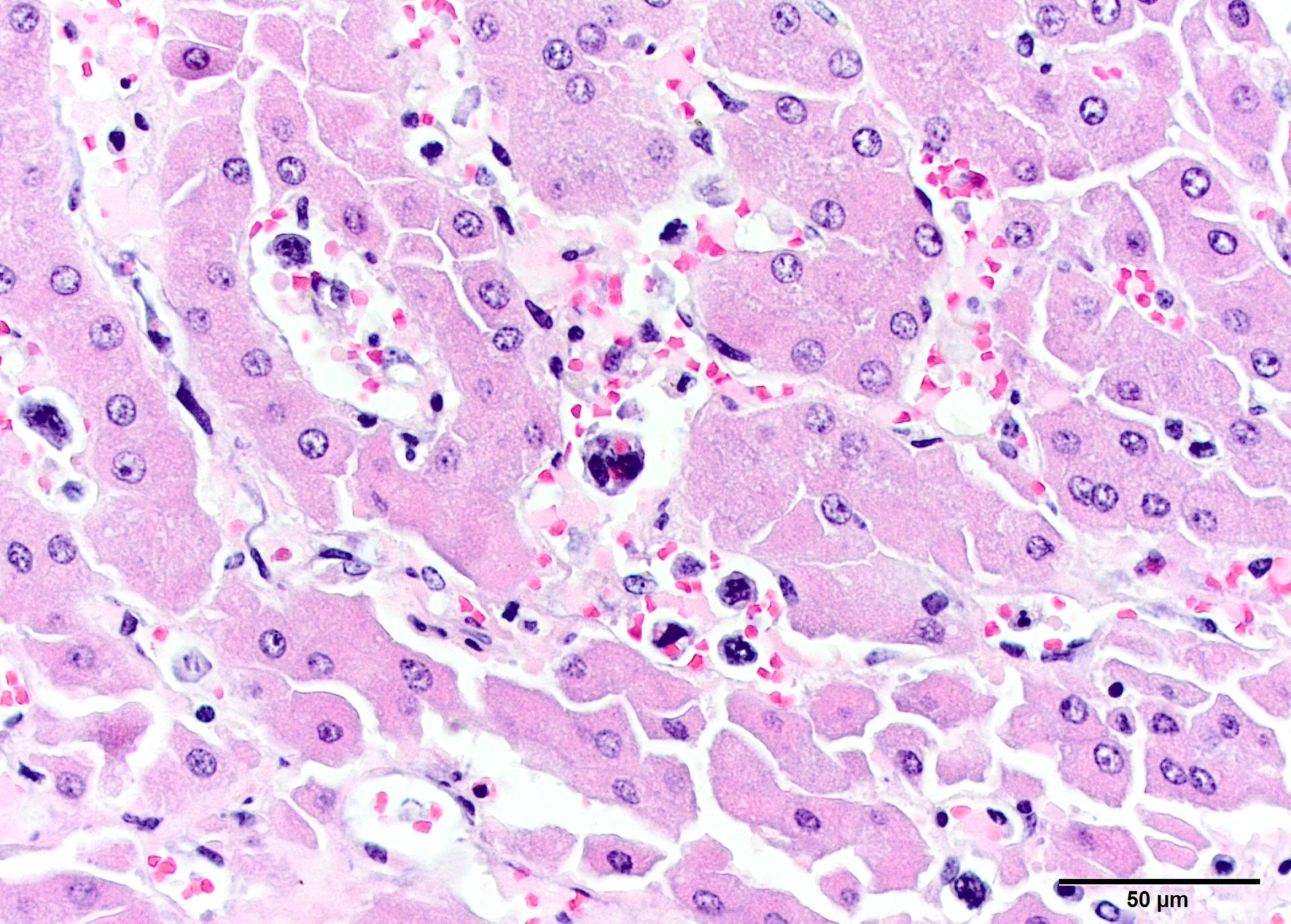

Large and small pulmonary vessels are congested, and there are contain numerous large nucleated cells located in alveolar capillaries. However, the cells are much less frequently present in larger arteries or veins. The cells have a defined outline and are polygonal in shape. They have large (even in relationship to cell size) polyhedral to reniform nuclei, with condensed chromatin. Occasional cells are multinucleate. Erythrophagia is common. Rare intravascular mitoses are found. In the liver, similar cells distend hepatic sinusoids, with atrophy of hepatic cords and degeneration. As in the lung, they have distinct cytoplasmic borders, large hyperchromatic nuclei and are erythrophagocytic. Additional similar cellular infiltrates were found in the spleen and in vessels but not in the parenchyma of the bone marrow.

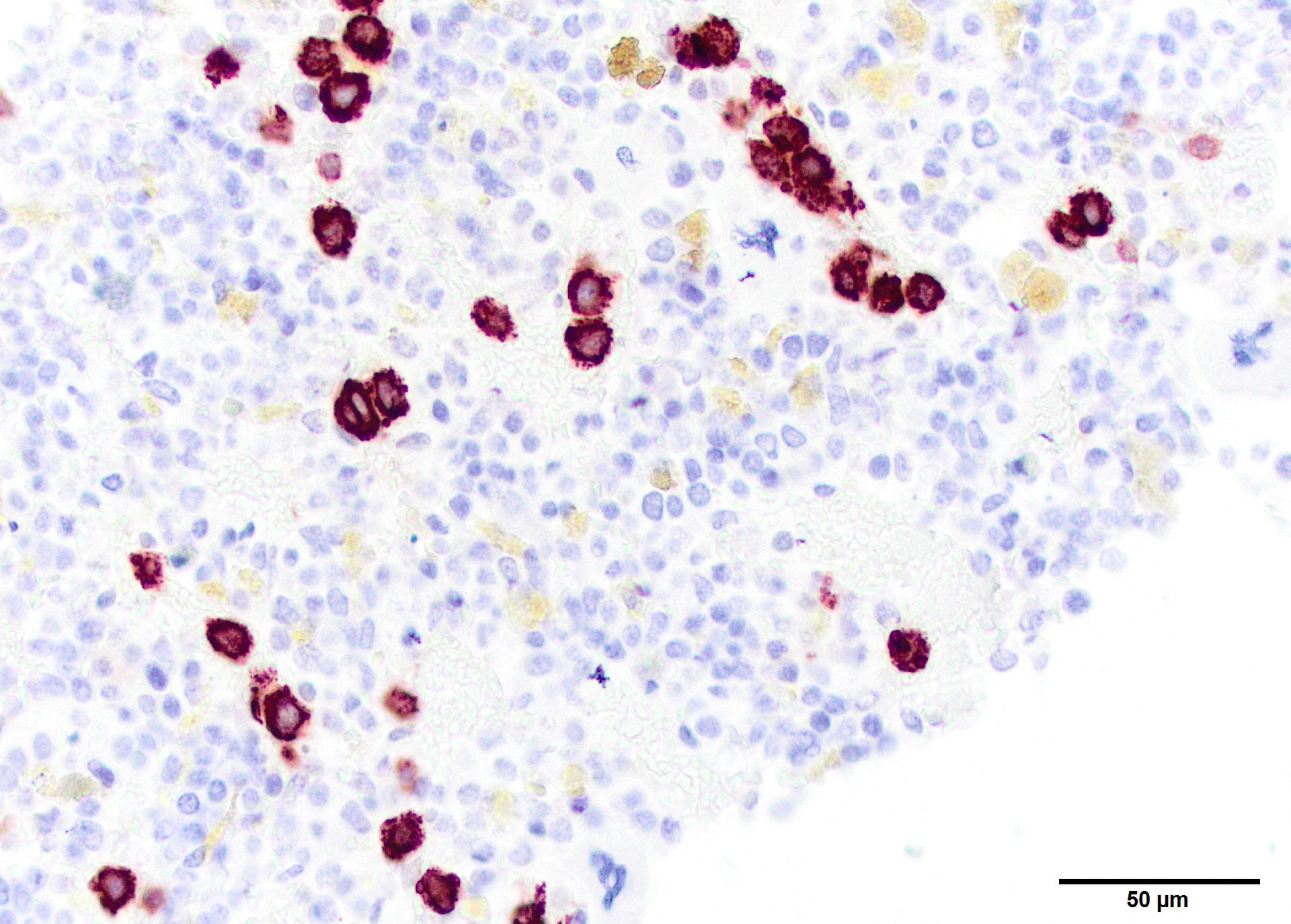

Immunohistochemistry identified the cells as CD3-positive. Positively staining cells have a linear arrangement in the marrow due to their intravascular location, which is not readily appreciated in the photo. CD20 staining identified a few small lymphocytes in the marrow itself. Numerous Iba-1 positive cells were present and appeared to be parenchymal, but co-localization of this marker with CD3 was not tested.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lung and liver: Intravascular (angiotrophic) lymphoma, multiple organs

Contributor’s Comment: Finding an intravascular lymphoma was entirely unexpected in this horse, which had been euthanized for intractable chronic cellulitis of one rear leg. Lymphoma is the most common malignant neoplasm of the hematopoietic system of horses, with the multicentric form being most common. B cell and T cell-rich B cell neoplasms are most common.1 Angiotrophic or intravascular lymphoma, also call lymphoid granulomatosis, is one of the least common types of lymphoma in any species. Different types of lymphoma are now considered specific diseases rather than a single entity.

Intravascular lymphoma is a rare disease and may be of B cell, T cell, or NK cell origin, in order of increasing rareness in people.2,4 Neoplastic cells are found only in small and medium-sized vessels, and it has been speculated that they cannot interact with the vascular wall to exit the circulation.2 In people, especially in the western hemisphere, most cases are large B cell lymphomas. They are often difficult to diagnose hematologically. In Asian countries, the T cell phenotype is more common.4 T cell tumors have been associated with HIV infection.2 Patients with intravascular lymphoma commonly present with fever, and fever due to this neoplasm might have been attributed to the leg infection in this horse. Hemophagia is very common, although in the past it had been attributed to red cell consumption macrophages in the tumor rather than tumor cells. No antemortem hematologic data was available for this patient. In our case, it is clear that the neoplastic cells are engulfing red cells. However, double immunolabeling was not done, and the possibility remains that this lymphoma could express both markers. Intravascular lymphoma cells typically reside in small arteries veins and capillaries instead of large vessels;6 this characteristic was present in the horse. Intravascular or angiotropic lymphoma has been called by others a “homeless lymphoma” and apparently lacks the ability to exits the vasculature. It is thought that lack of β-integrin or ICAM homing receptor may explain the inability of these cells to exit the intravascular space.

This neoplasm has a short list of differential diagnoses, includes histiocytic sarcoma/leukemia, lymphoid leukemia and intravascular lymphoma. Intravascular lymphoma has been described in an Australian horse that presented with anemia due to hemophagic syndrome.4

Participants in this case were split between a diagnosis of leukemia or intravascular lymphoma, both of which are viable diagnoses in the absence of bloodwork or the ability to evaluated peripheral blood or bone marrow specimens. The moderator brought up an interesting clinical aspect of intravascular lymphomas in animals, as that peripheral blood smears of intravascular lymphoma are often devoid of neoplastic cells, while leukemias will show a lymphocytosis as well as abnormal cells on a peripheral blood draw. Attendees also commented on the relative paucity of neoplastic cells in this particular case, while previous cases that they had seen (albeit all in dogs), contained numerous circulating neoplastic cells which often filled vessels in multiple organs. This may simply be a species difference.

The consensus of the participants is that the JPC diagnosis of “intravascular lymphoma with erythrophagocytosis” would be most appropriate in this case, as the poor preservation of the lung section as well as the pleomorphic nature of the cells precludes a more specific diagnosis in this case without the use of immunohistochemical markers.

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab and Department of Veterinary Pathobiology

http://vmdl.missouri.edu/, http://vpbio.missouri.edu/

JPC Diagnosis: Lung, liver: Intravascular lymphoma, with erythrophagocytosis.

JPC Comment: The contributor has supplied an excellent writeup of a unique case. Based solely on the morphology of the pleomorphic lymphocytes within the sinusoids and alveolar capillaries and their unfamiliarity with the syndrome in the horse, conference attendees preferred a diagnosis of intravascular lymphoma (IVL) until phenotyping information became available as the case was discussed.

Intravascular lymphoma is a rare entity in all species including humans. In humans, most cases of angiotropic are of B-cell origin. In the dog, in which the majority of this rare neoplasm has been reported, it is usually of T-cell origin. A previous case of cerebral intravascular lymphoma of presumptive T-cell origin was presented in WSC 2013-2014, Conference 6, case 2; dogs are also predisposed to develop this neoplasm within the nervous system.5

In the single previously reported case of IVL in a mare, antemortem diagnosis was not made, a common finding in IVL likely resulting of the variable involvement of somewhat random organs often seen in this condition. In that report, a mare with a viable 8-month fetus rapidly developed extravascular hemolysis and regenerative anemia as a result of erythrophagocytosis by an activated reticuloendothelial system (hemophagocytic syndrome), rather than by neoplastic cells as seen in this case.

A possible reason for the intravascular nature of the neoplastic cells comes from human cases, in which neoplastic B cells have demonstrated deficiencies in β1- (CD29) or β2-integrin (CD18) deficiencies. β-integrins are important in the leukocyte adhesion cascade, enabling leukocytes to exit blood vessels and migrate through tissue in order to participate in inflammation. The lack of these molecules may render neoplastic lymphocytes unable to exit vessels, resulting in high numbers within the vasculature.5

References:

- Valli VEO, Kiupel M, Bienzle D. Hematopoietic System. In Maxie G, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals Vol 3, 6th ed. Elsevier, Inc. St. Louis; 2016:237-238.

- Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJM. Intravascular lymphoma: a neoplasm of “homeless lymphocytes. Hematolo Oncol. 2006;24:105-112.

- Raidal SL, Clatk, P, Raidal SP. Angiotrophic T-cell lymphoma as a cause of regenerative anemia in a horse. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:1009-1013.

- Sukpanichnant S, Visuthisakchai S. Intravascular lympomatosis: a study of 20 cases in Thailand and review of the literature. Clinical lymphoma & Myeloma. 2006; 6(4):319-328.

- WSC 2013-2014, Conference 6, Case 2; http://www.askjpc.org/wsco/wsc_showcase4.php?id=djZ2eEQwNDZoc1NZZUNDTXB5R3lUZz09

- Yao X, Sadd A, Chitmbar CR. Intravascular B-cell lymphoma, and exclusively small vessel disease? Case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2010;34:275-77.