Signalment:

5-year-old, male, mongrel, dog (

Canis familiaris).The dog presented with apathy, anorexia, vomiting, and diarrhea with blood, icterus (Figs. 1 and 2), fever

(40.8°C), mild dehydration, tachycardia, dyspnea and subcutaneous edema in the pelvic limbs and generalized

enlargement of the lymph nodes.

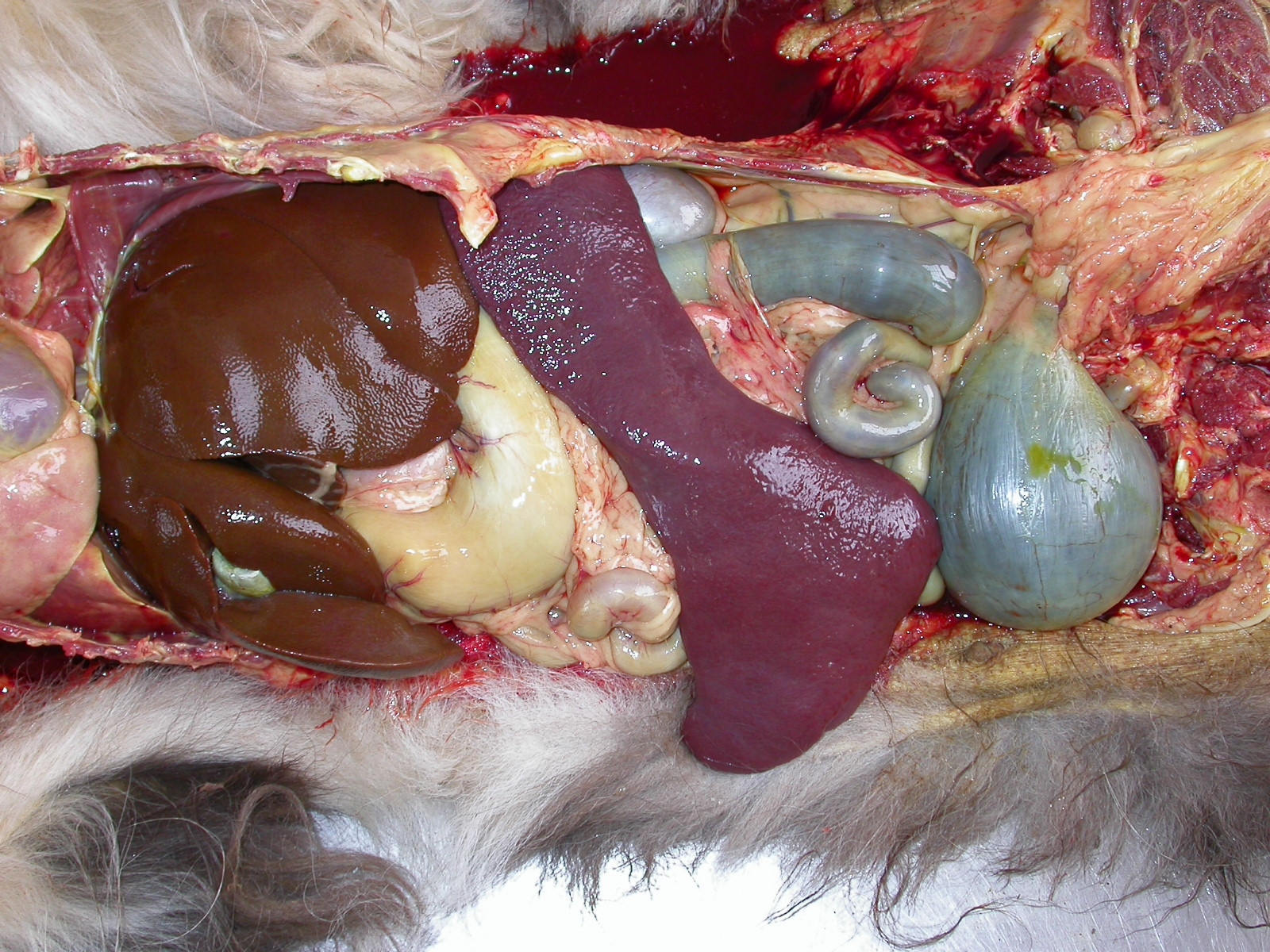

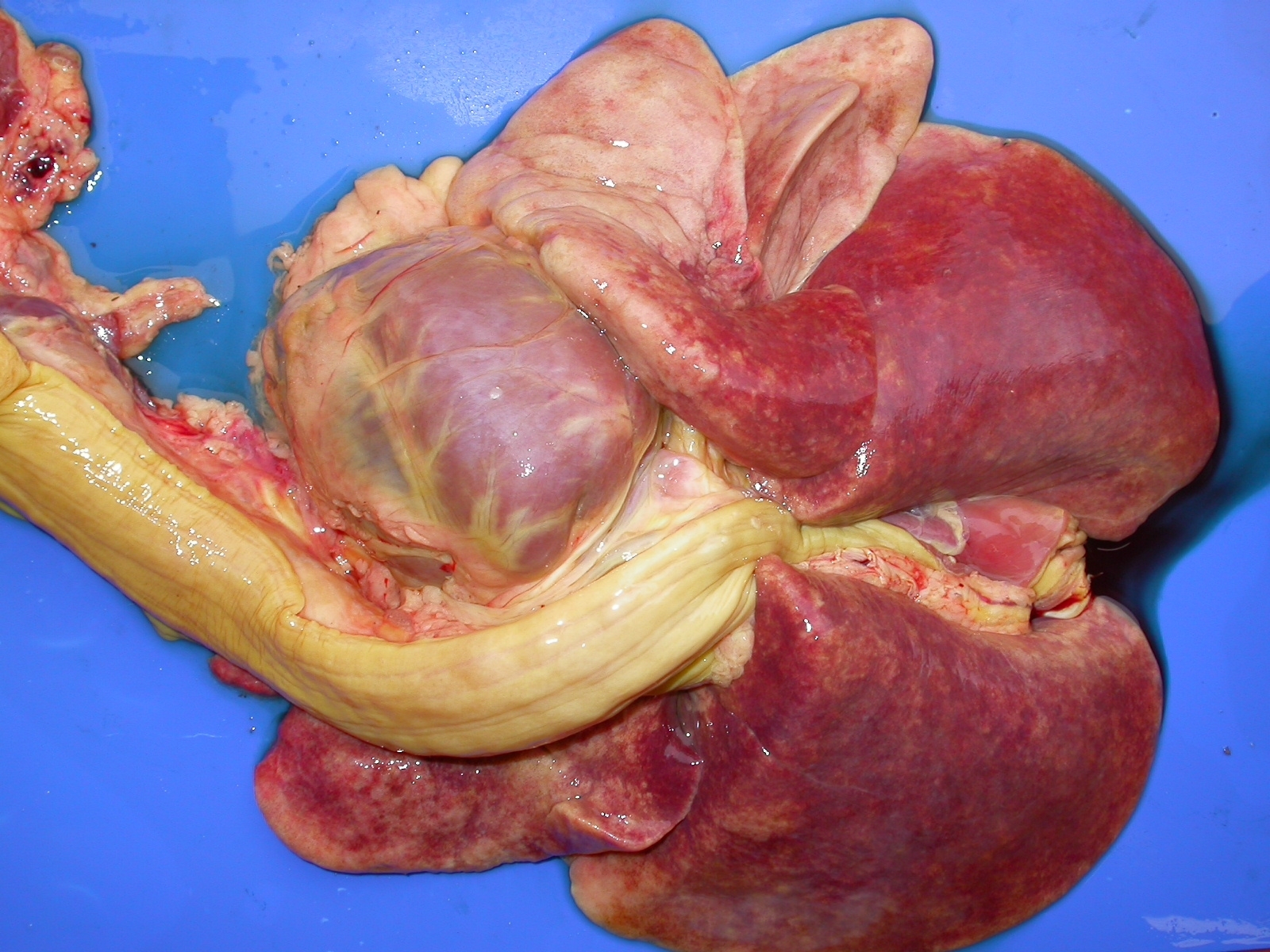

Gross Description:

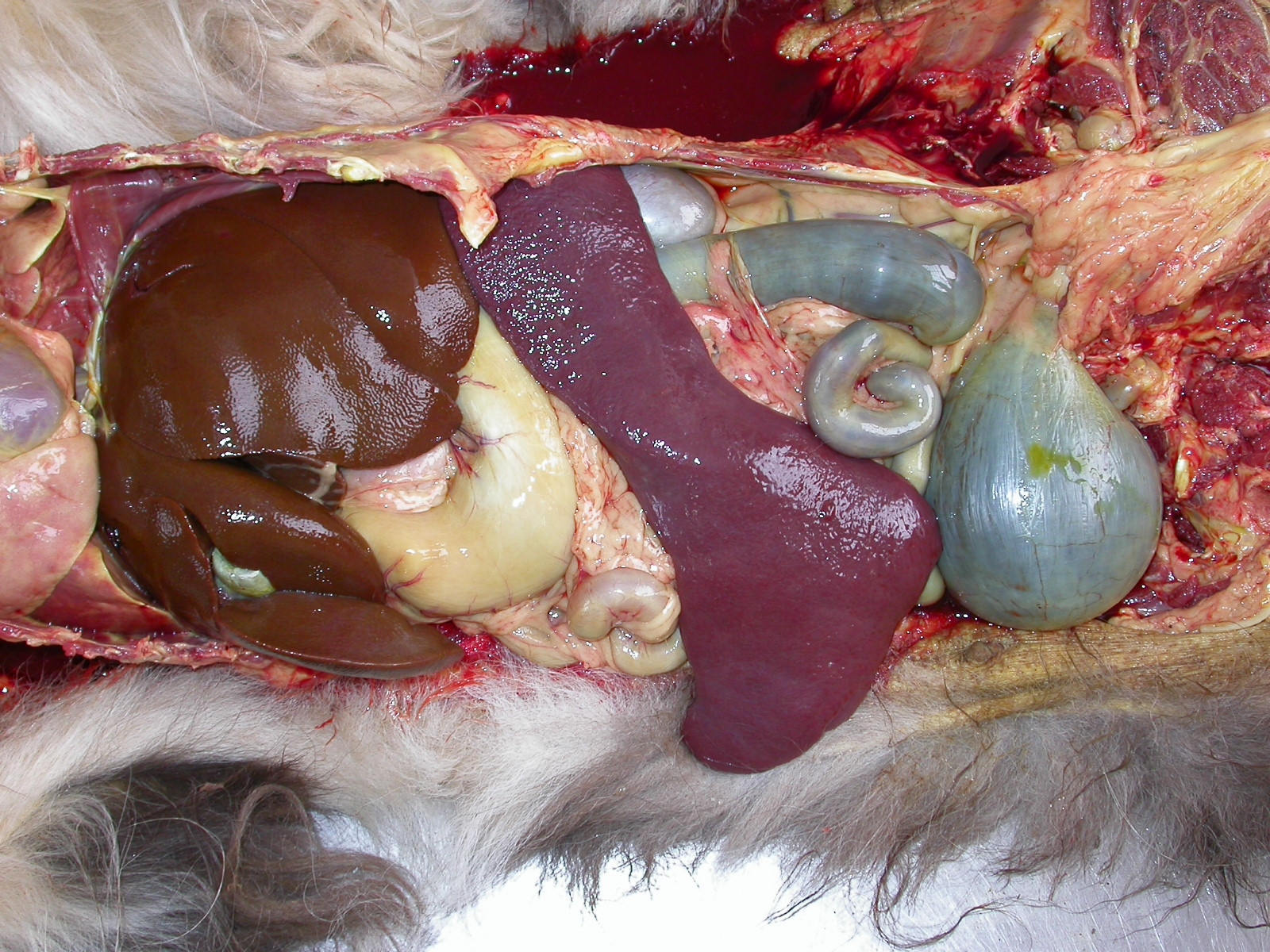

There was marked yellow discoloration (icterus) of mucous membranes, skin, subcutaneous

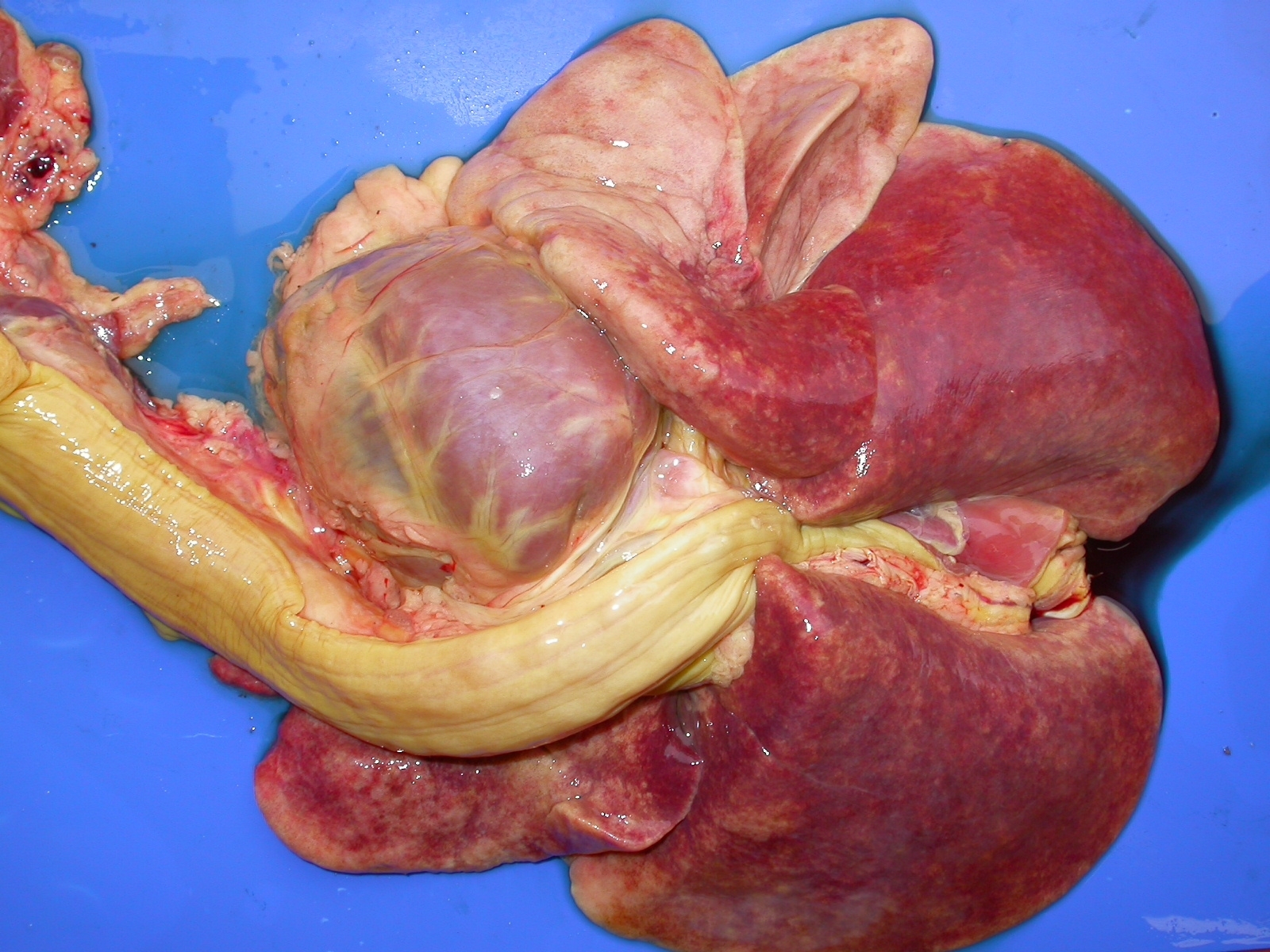

tissues and intima of large arteries. The spleen was markedly (about 5x) enlarged (Fig. 5) and had a dry (no blood

oozing) fleshy texture to the cut surface (Fig. 6). All lymph nodes were moderately enlarged, soft, light brown and

wet at cut surfaces. The mucosa of the entire small intestine was dark red (hemorrhagic) and the contents were

admixed with blood. The lungs were red and wet and did not collapse when the thoracic cavity was opened (Fig. 7).

Large amounts of fluid oozed from the cut surface of the lungs. A large amount of whitish-pink foam could be

observed within the trachea and main bronchi (pulmonary edema). Additional findings included serous atrophy in

the coronary adipose tissue of the heart, hydropericardium, petechiae and paint brush hemorrhages in the

endocardium of the left ventricle. The bone marrow of the long bones was markedly red and filled the whole

marrow space.

Histopathologic Description:

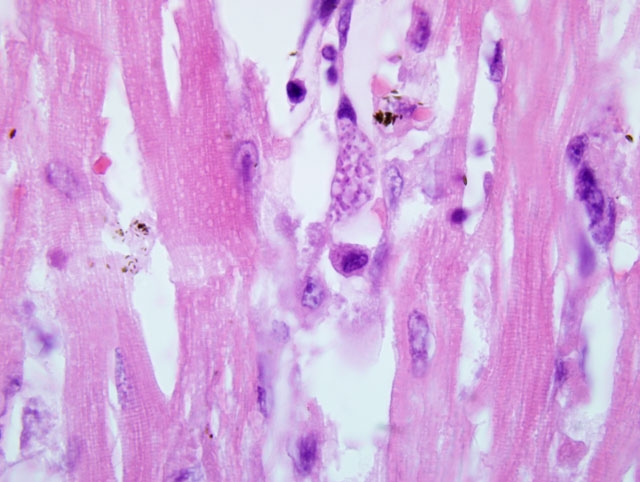

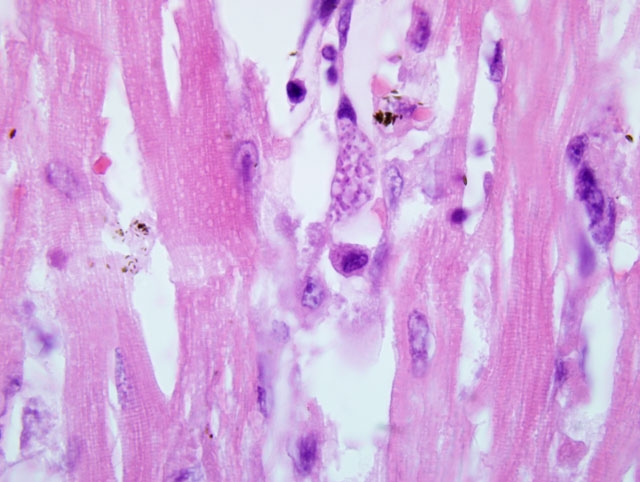

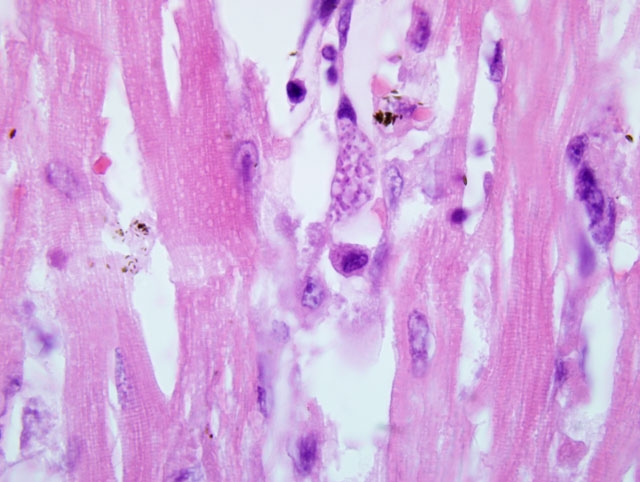

Spleen and heart: In the spleen there is a marked inflammatory infiltrate consisting

of some lymphocytes and large numbers of plasma cells. The cellular infiltrate obliterates a large part of the splenic

red pulp. There are few plasmablasts and Mott cells within the inflammatory infiltrate; however, the majority of the

inflammatory cells consists of mature plasma cells. Multiple aggregates of histiocytes are seen throughout the

spleen and compress the adjacent splenic tissue. Oval to round, 2μm protozoal organisms can be observed within

the cytoplasm of endothelial cells of the splenic capillaries, but not in venules, arterioles, veins or arteries. There are

5-20 organisms per parasitized cell. In the liver (not submitted), there was paracentral coagulative zonal necrosis;

the cholangioles and bile ductules were distended by bile pigment and there was a lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory

infiltrate in the portal triads. The same inflammatory infiltrate is observed in the myocardium, renal interstitium,

and pulmonary interalveolar septa. In the myocardium, the inflammatory infiltrate is associated with mild

degeneration of cardiomyocytes. Large numbers of nucleated RBCs occurred within hepatic sinusoids. The

protozoal organisms described in the spleen and myocardium can also be observed parasitizing endothelial cells of

capillaries in the kidney, lymph nodes, liver, bone marrow and choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle (Fig. 8).

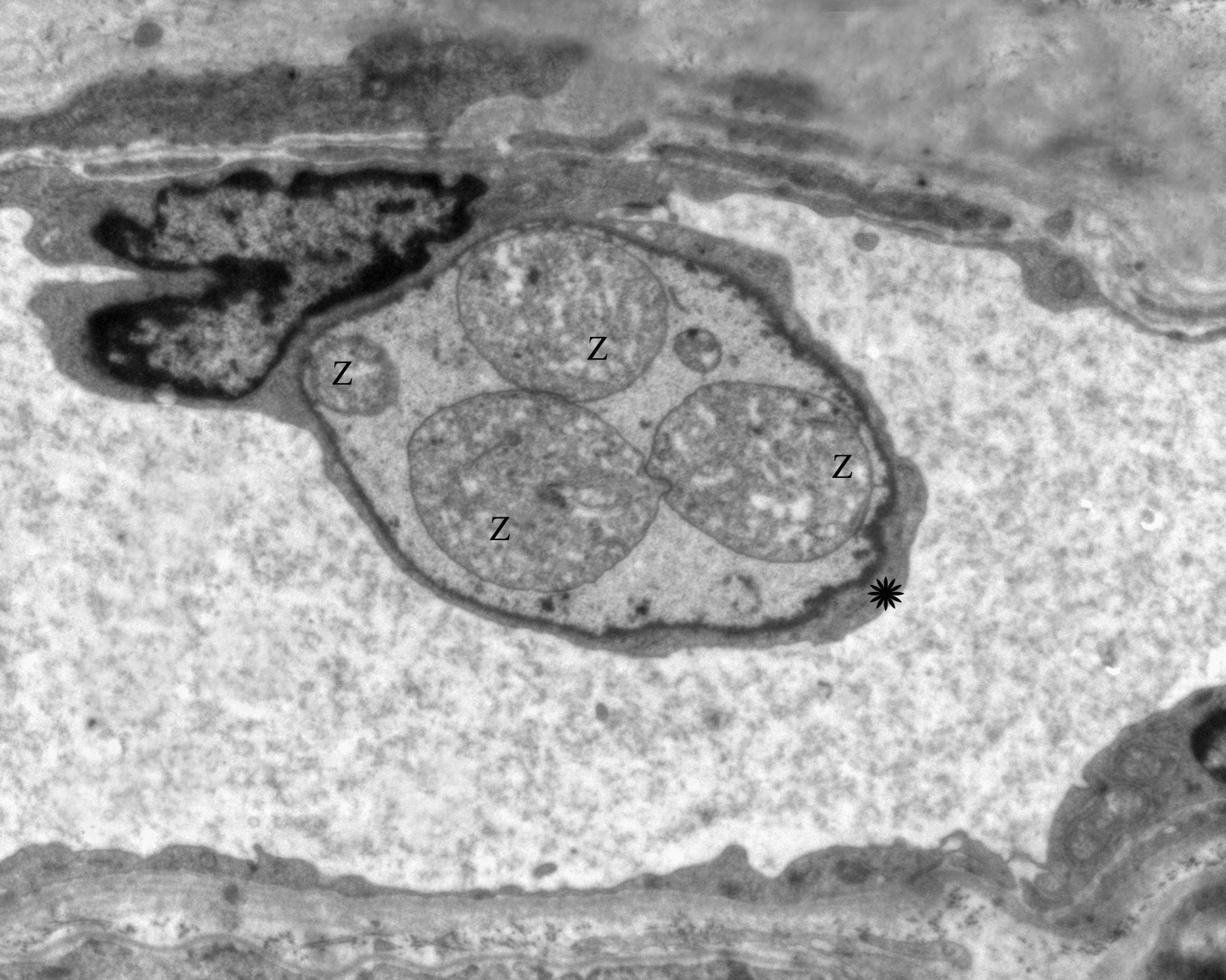

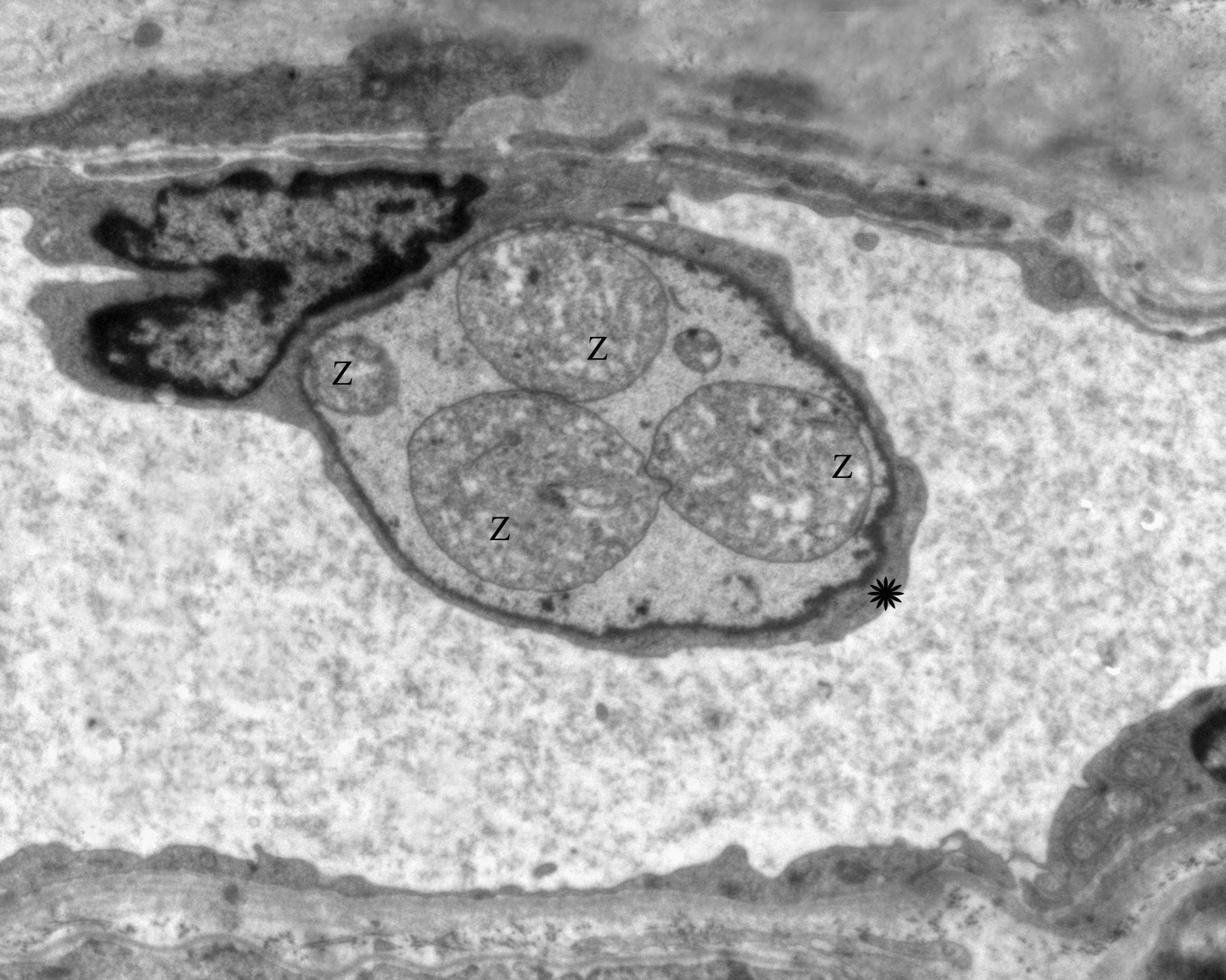

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the choroid plexus (Fig. 9) shows zoites (z) within the cytoplasm

(asterisk) of an endothelial cell. Zoites (z) can also be visualized by TEM within endothelial cells of a lymph node

(Fig. 10).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1) Spleen, reactive hyperplasia, lymphoplasmacytic, associated with

intraendothelial zoites, morphology consistent with

R. vitalii.Â

2) Myocardium, myocarditis, lymphoplasmacytic mild

to moderate, with mild fiber degeneration, associated with intraendothelial zoites, morphology consistent with

R.

vitalii.

Lab Results:

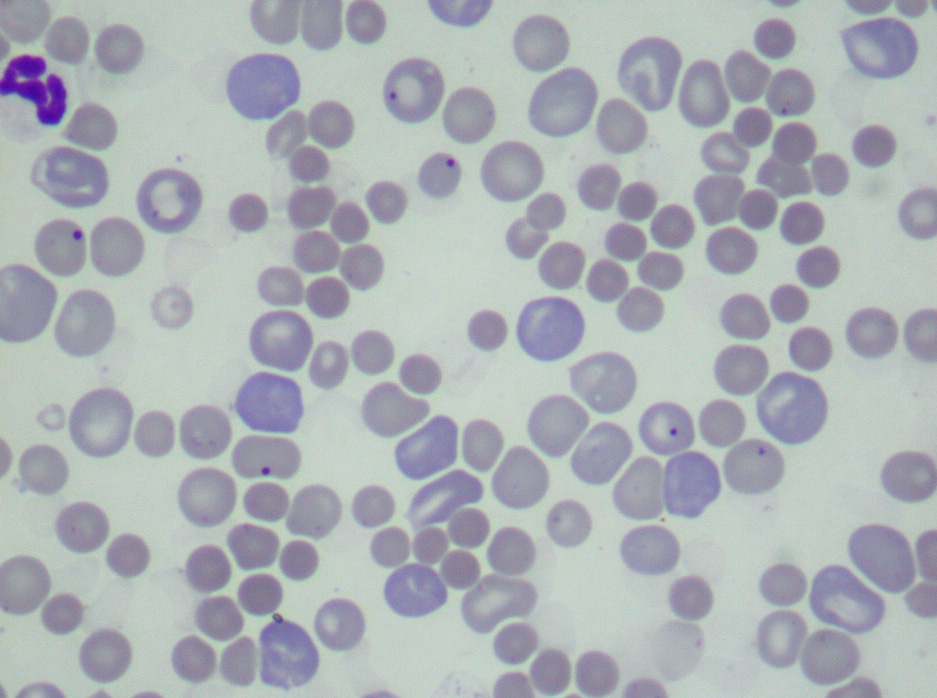

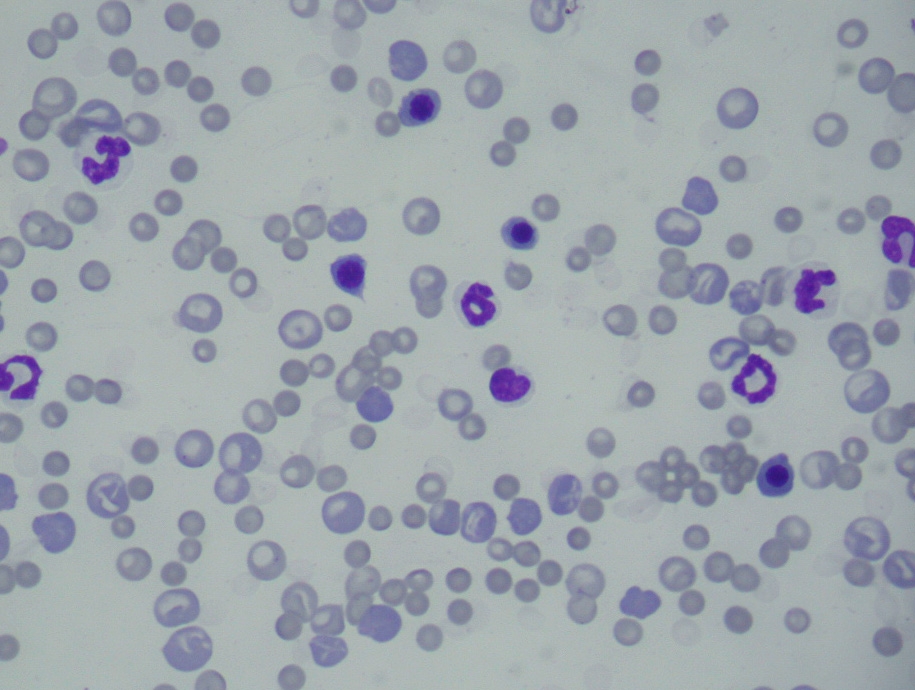

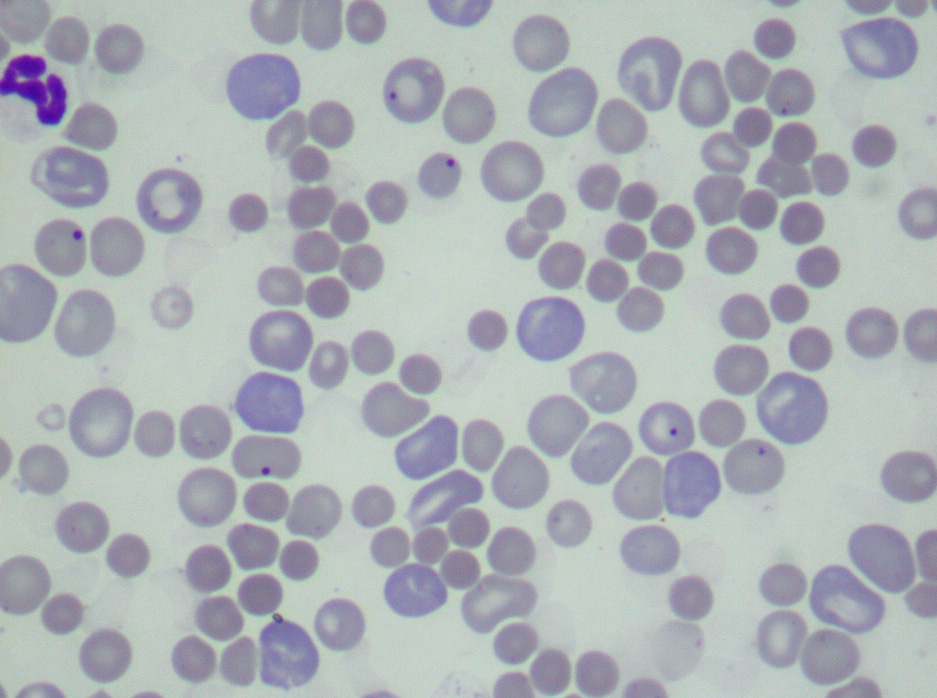

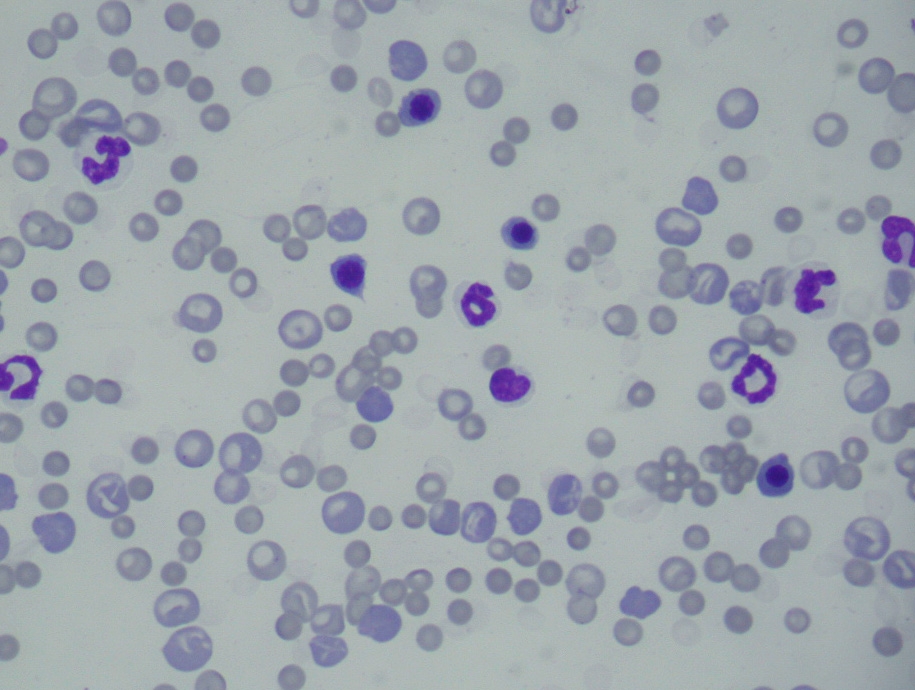

A CBC performed at presentation revealed hypochromic macrocytic regenerative anemia,

leucocytosis due to regenerative left shift and lymphocytosis, and regenerative thrombocytopenia (Table 1). Blood

smears revealed marked anisocytosis and polychromasia, several RBCs with Howell-Jolly bodies (Fig. 3), and large

numbers of nucleated RBCs, mainly metarubricytes (23/100 leucocytes), but also lesser numbers of rubricytes

(2/100 leucocytes) (Fig. 4). Marked spherocytosis (Fig. 3) and large platelets (macroplatelets) were additional

findings in the blood smear. No blood parasites were found neither within blood cells nor free in the plasma.

The biochemistry panels showed mild increase in total plasma proteins due to increase in albumin, moderate

increase in serum activity of alanine aminotransferase and marked increase in the total serum bilirubin (Table 2).

Urinalysis revealed marked bilirubinuria.

Based on the laboratory results described above, a clinical diagnosis of extravascular hemolytic anemia was

established. The marked spherocytosis suggested an immune mediated origin. The dog was treated with 1 mg/kg

prednisone but died the following day.

Table 1 - CBC (reference values are within parentheses)

| WBCs (/mm3) | 32200 | (6,000-17.000) | RBCs (x106/mm3) | 1.3 | (5.5-8.5) |

| Neutrophils (%) | 72 | (60%-77%) | | | |

| Neutrophils (abs.) | 23184 | (3,000-11,500) | | | |

| Bands (%) | 6 | (0%-3%) | Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 3.8 | (12.0-18.0) |

| Bands (abs.) | 1932 | (0-300) | | | |

| Metamyelocytes (%) | 2 | (0%) | | | |

| Metamyelocytes (abs.) | 644 | 0 | Hematocrit (%) | 12 | (37-55) |

| Myelocytes (%) | - | (0%) | | | |

| Myelocytes (abs.) | - | 0 | | | |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 17 | (12%-30%) | MCV (fl) | 92.3 | (60.0-77.0) |

| Lymphocytes (abs.) | 5474 | (1,000-4,800) | | | |

| Monocytes (%) | 2 | (3%-10%) | | | |

| Monocytes (abs.) | 644 | (150-1,350) | MCHC (%) | 31.7 | (32.0-36.0) |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1 | (2%-10%) | | | |

| Eosinophils (abs.) | 322 | (100-1,250) | | | |

| Basophils (%) | - | (rare) | Platelets (x103/mm3) | 98 | (200-500) |

| Basophils (abs.) | - | (rare) | | | |

Table 2 - Biochemistry panel

| Parameter | Unit | Result | Reference values |

| Alanine aminotransferase | U/L | 180 | 4.0-24.0 |

| Albumin | g/dL | 4.4 | 2.6-3.3 |

| Creatinine | mg/dL | 1.2 | 0.5-1.5 |

| Total bilirubin | mg/dL | 6.5 | 0.1-0.5 |

| Fibrinogen | mg/dL | 200 | 200-400 |

| Globulins | g/dL | 4.2 | 2.7-4.4 |

| Total plasm proteins | g/dL | 8.8 | 6.0-8.0 |

| BUN | mg/dL | 56.0 | 21.0-60.0 |

Condition: Rangelia vitalii

Contributor Comment:

Based up on the clinicopathological findings, a diagnosis of hemolytic anemia

associated with infection by Rangelia vitalii (rangeliosis) was made. Rangeliosis, colloquially known as nambi-uv+�°

(in native Brazilian Indian idiom meaning literally bleeding ear), peste de sangue and febre amarela dos

c+�-�es (Portuguese for blood ill and yellow fever of dogs, respectively) is an extravascular hemolytic disorder

affecting dogs from southern Brazil. For several reasons this disease remained almost forgotten for the last 50 years,

and during this period it was variably mistakenly diagnosed as other canine infectious diseases (hemolytic or

otherwise), such as babesiosis, erlichiosis and leishmaniasis. The true nature of the disease surfaced again in 2001

when a group of Brazilian researchers put forth an effort to elucidate its cause, pathogenesis and etiology, and thus

established it as a distinct disease entity of dogs. (3,4,6) Although the precise taxonomic classification of the causative

organism of rangeliosis is still uncertain, the agent was established as a protozoal organism of the phylum

Apicomplexa, order Piroplasmorida based on ultrastructural, immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization studies.

(5) Until definitive nomenclature is established, Rangelia vitalii (named after two Brazilian researchers from the

first half of the 20th Century - Rangel and Vital ) is maintained as the parasites designation.

It is currently accepted that R. vitalii is transmitted by tick vectors (Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Amblyomma

aureolatum) to dogs and several wild mammal species in the State of Rio Grande do Sul (RS) in southern Brazil.

The life cycle of R. vitalii is unknown, but it has been speculated that the vectors R. sanguineus and A. aureolatum

circulate the protozoan between wild mammals and domestic dogs, the latter probably being an aberrant host.(3)

Experimental transmission to susceptible dogs using blood from spontaneously affected dogs was achieved recently

in two independent studies.(4,5) The clinical and laboratory aspects of experimental disease differ somewhat from

natural disease, suggesting that the parasite needs to replicate in the tick in order to acquire some aspects of

virulence. Experimental disease is also fatal if left untreated.

The great majority of dogs with spontaneous rangeliosis develop clinical signs of extravascular hemolysis: pallor of

mucous membranes; icterus; and hepatosplenomegaly.(3,4) Other clinical signs include apathy, anorexia, fever,

vomiting, diarrhea, mucopurulent oculonasal discharge, tachypnea, tachycardia, subcutaneous edema of the pelvic

limbs, and petechiae and ecchymosis on the mucous membranes.(3)

Hematologic findings are typical of extravascular hemolysis and include hypochromic macrocytic anemia with

excessive regeneration. Anisocytosis, polychromasia, Howell-Jolly bodies and several nucleated red blood cell

precursors (metarubricytes and rubricytes) are observed on peripheral blood smears.(3,4) Most of the affected dogs

also present varying degrees of spherocytosis,(3,4) a hematological finding highly suggestive of immune mediated

hemolytic anemia.(1) The numbers of circulating reticulocytes are high (5%-28%, average 12,5%).

Erythrophagocytosis is occasionally observed, particularly in those cases in which there is marked associated

spherocytosis. Normochromic normocytic anemia is observed on occasion due to the extreme contrast between the

small and falsely hypochromic-appearing spherocytes and the large polychromatophils recently released from the

bone marrow. Plasma from affected dogs is bright yellow. WBC counts frequently reveals leucocytosis due to

regenerative left shift resulting from long-standing and non-specific stimulation on the bone marrow. In some of the

cases the leucocytosis may present as a leukemoid reaction. Other common hematological findings include

lymphocytosis and monocytosis.(3)

In a smaller percentage of the cases of spontaneous canine rangeliosis, affected dogs develop a bleeding disorder

similar to DIC characterized by extensive hemorrhage from the tips, margins, and outer surface of the pinnae.(5) Dogs

affected in this manner have a moderate decrease in platelet numbers; numerous large platelets are observed in the

circulation, indicating regenerative thrombocytopenia. However, due to its moderate intensity, it is apparent that

thrombocytopenia itself is insufficient to induce the hemorrhage in these dogs, and some other disorder(s) of

hemostasis may be in place.(3,4)

There is no specific biochemical test for the diagnosis of rangeliosis, but serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is

increased in most cases. This elevation most likely results from anemia, hypoxia of centrolobular hepatocytes, and

death of these cells. Bilirubin levels are consistently increased due to the extravascular hemolysis and the urine is

darkened by the excretion of large amounts of bilirubin and urobilinogen; hemoglobinuria is never part of the

clinical picture.(3)

In contrast to most infectious hemolytic anemias, the clinical diagnosis of rangeliosis is generally made on response

to therapy, since the parasite is seldom found in the blood smears from affected dogs (only in approximately 4% of

the cases).(3) Currently, there is no commercial or in-house tests to detect antibodies or antigens associated with R.

vitalii. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) or excisional biopsy of lymph nodes, spleen and bone marrow with subsequent

cytological evaluation can also be important aids in the clinical diagnosis. Due to the intraendothelial location of the

parasite, fine needle aspiration may yield false negative results.

Necropsy findings in dogs dying from rangeliosis are consistent with those seen in other causes of extravascular

hemolysis. The mucous membranes, subcutaneous tissue, muscle fascia, serosal surfaces and arterial intima are

markedly icteric and peripheral blood is thin and watery. The liver is enlarged and has a red-orange hue or, in more

severe cases, a greenish discoloration. Accentuation of the hepatic lobular pattern is common. The spleen is

enlarged and fleshy and all lymph nodes are swollen, moist, and red,(3) and may have multifocal to coalescing white

areas.(5) Hyperplastic bone marrow is markedly red and fills the entire marrow space.

Microscopic evaluation of lymph nodes reveals marked erythrophagocytosis and, depending on the stage of the

disease, there is hemosiderosis and severe paracortical lymphoid hyperplasia. In the spleen, there is lymphoid

hyperplasia characterized by marked plasmacytosis which, in some cases, resembles the plasma cell proliferation

pattern observed in myelomas; however, in rangeliosis, most plasma cells are mature and there are few plasmablasts,

Mott cells and/or flame cells.(3)

In non-lymphoid organs, the same lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates are observed, and occasionally there is a

granulomatous infiltrate which includes multinucleate giant cells that sometimes phagocytize parasitized endothelial

cells.(4) In the liver, there is centrolibular coagulative necrosis and accumulation of bile pigment. In the bone

marrow, there is marked erythroid and megakaryocytic hyperplasia characterized by replacement of the marrow

adipose tissue by hematopoietic cells with high mitotic index, a drop in the myeloid to erythroid ratio, and increased

numbers of megakaryocytes and megakaryoblasts. Foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis can be observed

frequently in the spleen and liver and less frequently in the lymph nodes and adrenal glands.(3)

The parasite is found within the cytoplasm of endothelial cells in several organs and consists of 2.0-2.5 μm round to

oval, basophilic organism when stained with hematoxylin and eosin; its cytoplasm is pale and inconspicuous and the

nucleus is prominent, basophilic and eccentrically located.3,5 The frequency in which the parasite was observed in

several organs was reported from the study of 11 cases of canine rangeliosis as: kidneys (7/11), lymph nodes (7/11),

liver (6/11), bone marrow (4/11), spleen (3/11), tonsils (2/11), lung, brain, stomach and gallbladder (1/11).(4) The

authors pointed out that not all organs were histologically examined in each of the 11 cases. Other reports indicate

lymph nodes, bone marrow, kidneys and choroid plexus are the organs with the highest parasite load.(4) About 20-30

organisms can be found within the cytoplasm of each parasitized endothelial cell. The organisms usually can be

seen in smears from bone marrow sampled during the necropsy and stained with Giemsa and Panoptic.(4) In various

reports, immunostaining for Leishmania chagasi, Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii was consistently

negative;(4,5) however, the parasite reacted positively with an anti-Babesia microti antibody.(5) R. vitalii was also

positive on in situ hybridization for B. microti(4) indicating that the organism belongs to the same group as Babesia

However, unlike babesia R. vitalii is characterized by an intraendothelial stage. Parasitized cells are immunopositive

for Willebrand factor, indicating their endothelial nature. The ultrastructural characteristics of R. vitalii were

reported by Loretti & Barros 2005 (these authors mistakenly spelled the parasites name as R. vitalli) as having an

apical complex that includes a polar ring and rhoptries but no conoid; the parasite is contained within a

parasitophorous vacuole that had a trilaminar membrane with villar protrusions and was located within the

cytoplasm of capillary endothelial cells.(6)

Necropsy finding of dogs dying from rangeliosis, coupled with the hematological findings, suggest the diagnosis of

hemolytic anemia; the finding of the causative agent in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells confirms a presumptive

diagnosis.

Differentials for this case should include infection by R. vitalii, Histoplasma capsulatum, Trypanosoma cruzi,

Leishmania spp., Toxoplasma gondii, and Neospora caninum. Histoplasma and Leishmania organisms are typically

found in macrophages and may elicit an intense histiocytic to granulomatous response. H. capsulatum yeasts stain

with PAS and GMS stains. Leishmania and T. cruzi have a kinetoplast, which is absent in R. vitalii. Additionally,

the amastigotes of T. cruzi form pseudocysts within the sarcoplasm of cardiomyocytes and not within endothelial

cells. The zoites of T. gondii and N. caninum form 2-5 μm and 4-7 μm tachyzoites, respectively, and have no

kinetoplast. N. caninum can parasitize endothelial cells but usually parasitize a large spectrum of host cells and are

PAS positive. Similarly, T. gondii affects a large spectrum of host cells, although usually not endothelial cells, and

induces a whole different set of lesions.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Heart: Myocarditis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, multifocal, mild to moderate with

cardiomyocyte degeneration, capillary fibrin thrombi and numerous intraendothelial protozoa.

2. Spleen: Plasmacytosis, diffuse, marked with multifocal reticuloendothelial cell hyperplasia and scattered

intraendothelial protozoa.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent, thorough discussion of this unique and poorlyknown

infection. Conference participants were unfamiliar with this condition. Many favored T. cruzi. The key

observation necessary to reach the correct diagnosis is the intraendothelial location of the organism. Once that is

recognized, internet searches could lead to articles on this fascinating disease.

While reviewing the submitted CBC, biochemistry panel and cytology, conference participants discussed the

clinicopathologic differentiation between extravascular and intravascular hemolysis. The diagnostic features for

each are briefly summarized in the chart below.(2)

| | Extravascular Hemolysis | Intravascular Hemolysis |

| Cause (general categories) |

1. Antibody and/or complement mediated

2. Decreased RBC deformability

3. Premature RBC aging (decreased glycolysis

and [ATP])

4. Increased macrophage phagocytosis |

1. Complement-mediated lysis

2. Physical damage

3. Oxidative damage

4. Osmotic lysis

5. Membrane alterations

|

| Onset | Usually chronic course with insidious onset | Peracute to acute |

| CBC | Neutrophilia, monocytosis, thrombocytosis | No significant findings |

| Biochemistry | Hyperbilirubinemia with the unconjugated

form dominating early |

1. Hemoglobinemia: plasma discolored red;

increased MCHC and MCH; decreased serum

haptoglobin

2. Hyperbilirubinemia with unconjugated

dominating early |

| Urinalysis | Bilirubinuria | Hemoglobinuria; hemosiderinuria; -�

Bilirubinuria |

| Erythrocyte

morphology |

Spherocytes, schistocytes, keratocytes; if a

regenerative response, reticulocytes, Howell-

Jolly bodies, polychromasia and macrocytosis |

Schistocytes, keratocytes, Heinz bodies,

eccentrocytes |

Certain breeds of dogs and cats possess hereditary biochemical deficiencies or predispositions to extravascular

hemolysis.(2) In dogs, phosphofructokinase deficiency is seen in cocker spaniels, English springer spaniels and some

mixed breeds. Pyruvate kinase deficiency is noted to occur in the Basenji, beagle, Chihuahua, dachshund, pug,

miniature poodle, West Highland White terrier, and Cairn terriers as well as Abyssinian, Somali and domestic shorthaired

cats. A hereditary predisposition to hemolytic anemia is suspected in the border collie, cocker spaniel,

English springer spaniel, German shepherd dog, Irish setter, Old English sheepdog, poodle and the whippet.

References:

1. Barker RN. Anemia associated with immune responses. In: Feldman BF, Zinkl JG, Jain NC, eds. Schalms

Veterinary Hematology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2000:169-177.

2. Brockus CW, Andreasen CB. Erythrocytes. In: Latimer KS, Mahaffey EA, Prasse KW, eds. Duncan and Prasses

Veterinary Laboratory Medicine: Clinical Pathology. 4th ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2003:26-38.

3. Fighera RA: Rangeliose. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae 2007;35(Supl2):264-266.

4. Krauspenhar C, Fighera RA, Gra+�-�a DL. Anemia hemol+�-�tica em c+�-�es associada a protozo+�-�rios. MEDVEP

2008;1:273-281.

5. Loretti A, Barros SS. Hemorrhagic disease in dogs infected with an unclassified intraendothelial piroplasm in

southern Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:193-213.

6. Loretti A, Barros SS: Infec+�-�+�-�o por Rangelia vitalli (Nambiuv+�°, Peste de Sangue) em caninos: revis+�-�o.

MEDVEP. 2004;2:128-144.

Click the slide to view.

4-1. Oral mucosa

4-2. Skin

4-3. Spleen

4-4. Spleen

4-5. Heart and lung

4-6. Peripheral blood

4-7. Peripheral blood

4-8. Heart

4-8. Heart

4-9. Choroid plexus, endothelial cell

| Back | VP Home |

Contact Us |