Signalment:

Gross Description:

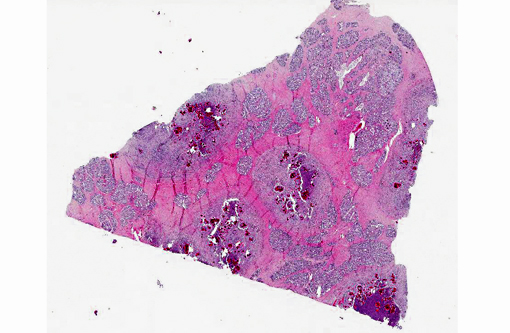

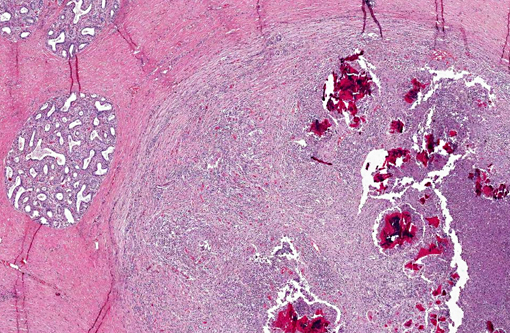

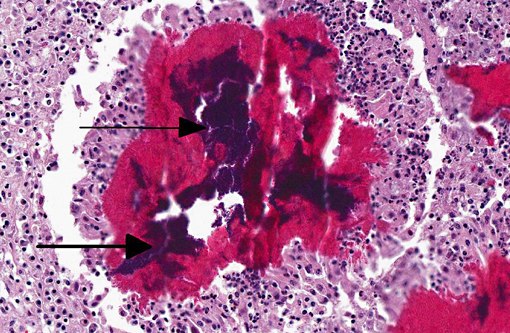

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

S. aureus is one of the most common causes of bovine mastitis. Clinically, staphylococcal mastitis may be peracute and fulminating or milder and more chronic. The acute forms of disease generally occur shortly after parturition and tend to produce gangrene of the affected quarters with high mortality.(9) The chronic or subclinical forms are more common and thus associated with the most important economic losses. The clinical presentation may be related to the strain of S. aureus; strains differ in their ability to spread within herds, and to cause somatic cell count elevation, clinical mastitis, or persistent infections or loss in milk production. In vitro, strains differ in their ability to withstand killing by neutrophils or invade mammary epithelial cells.(1)

The main reservoirs of infection are infected quarters and lesions on the skin of the udder and teat. Once S. aureus contaminates the teat orifice, it can persist and multiply before entering the teat canal and sinus and disseminating within the mammary gland. Colonization of the distal part of the mammary gland may be achieved by adhesion to specific receptors on the surface of epithelial cells. The adhesion varies from very low to extremely high numbers of bacteria per cell. In vitro adhesion depends on multiple factors including strain and origin of mammary epithelial cells.(5) The host response to the penetration includes degeneration and necrosis of epithelial cells and exudation of neutrophils into the interlobular tissue and secretory acini. If the exudation is massive and the organisms highly toxigenic, the acute and gangrenous forms of the disease occur. S. aureus can also invade more deeply into the inter-acinar tissue and establish persistent foci of infection that provoke botryomycotic granulomatous reactions associated with marked fibroplasia.(9) Acinar atrophy may be due to pressure from this fibrosis and also from occlusion of small ducts by exudate or granulation tissue causing obstruction of milk flow from unaffected lobules.(9)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly reported etiology of mastitis. S. aureus isolates range from nonpathogenic to highly pathogenic; catalase and hemolysin production are the best indicators of bacterial pathogenicity.(4,9) Factors in normal milk which inhibit bacterial growth are listed in table one.(7,9) S. aureus has developed multiple virulence factors to overcome these defense mechanisms, which are listed in table two.(2-5,7)

Although most problematic in cattle, mastitis also affects many other domestic animal species. The major agents recovered from sheep and goats with necrotizing or gangrenous mastitis are S. aureus and Mannheimia haemolytica. For mycoplasmal mastitis, the typical causative agents are Mycoplasma agalactiae or M. mycoides. Additionally, goats and sheep infected with the small ruminant lentiviruses, caprine arthritis and encephalitis virus and maedi-visna virus, respectively, develop hard udders with agalactia. Equine mastitis is sporadic, and Streptococcus zooepidemicus is the typical cause.(4,7,9) In swine, mastitis usually occurs in lactating or recently weaned sows. Gram-negative coliforms are the most commonly isolated etiologic agents; gram-positive bacteria such as Streptcoccus, Staphylococcus and Aerococcus spp. are reported less frequently.(6) In dogs and cats mastitis is uncommon; dogs are more likely to present with mammary neoplasia, while fibroadenomatous hyperplasia (mammary hyptertrophy) is the most prevalent mammary lesion in cats. When present in dogs or cats, mastitis tends to occur in early lactation, due to Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. or E. coli entering lactiferous ducts via fissures in nipples.(4) E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus zooepidemicus are commonly encountered in guinea pig mastitis, while S. aureus (type C) and Pasturella multocida tend to affect rabbits. Mastitis is also reported in rats (typically due to Pasteurella pneumotropica, S. aureus, Corynebacterium spp., or Pseudomonas spp.), and hamsters (beta-hemolytic Streptococcus spp., P. pneumotropica, E. coli).(8)

Table 1. Antibacterial factors in milk. (7,9)

| Antibacterial Factor | |

| Phagocytic cells | Phagocytosis is less efficient in milk than in serum |

| Lactoferrin | Iron-binding protein that inhibits bacterial multiplication |

| Lysozyme | Lyses bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan |

| Lactoperoxidase | May inhibit S. aureus and streptococci |

| Hydrogen peroxide | A weak oxidizing agent that is a byproduct of bacterial fermentation of milk carbohydrates |

| Immunoglobulins | Primarily IgG, which promotes opsonization; less IgA, which may reduce bacterial adherence at epithelial surfaces |

Table 2. Select virulence factors of S. aureus.(2-5,7)

| Virulence Factor | |

| Leucocidin | Cytolytic to bovine leukocytes |

| Alpha-toxin | Binds cell membranes forming hexameric pores; not produced by all S. aureus isolates |

| Beta-toxin | A phospholipase C or sphingomyelinase |

| Protein A | Antiphagocytic factor that binds to the Fc fragment of IgG |

| Extracellular enzymes | Coagulase, hyaluronidase, phosphatase, nuclease, lipase, catalase, staphylokinase (fibrinolysin), superantigens and proteases |

| Bacterial capsule | Interferes with opsonization, phagocytosis, and complement activity; not present in all strains of S. aureus |

| Penicillinase | Splits beta-lactam ring of penicillin |

References:

1. Barkema, HW, Schukken YH, Zadoks RN. Invited review: The role of cow, pathogen, and treatment regimen in the therapeutic success of bovine Staphylococcus aureus mastitis. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:1877-1895.

2. Biberstein EL, Hirsh DC. Staphylococci. In: Hirsh DC, Zee YC, eds. Veterinary Microbiology. Malden, MA: 1999:115-119.

3. DeDent AC, McAdow M, Schneewind O. Distribution of protein A on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacter. 2007;189(12):4473-4484.

4. Foster RA. Female reproductive system and mammary gland. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:198, 1121-1124.Â

5. Kerro Dego O, van Dijk JE, Nederbragt H. Factors involved in the early pathogenesis of bovine Staphylococcus aureus mastitis with emphasis on bacterial adhesion and invasion. A review. Vet Quart. 2002;24:181-198.Â

6. Martineau GP, Farmer C, Peltoniemi O. Mammary System. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:282-285.

7. Morin DE. Mammary gland health and disorders. In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1112-1143.Â

8. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:192, 231-232, 281, 283.Â

9. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:550-564.Â