Signalment:

An 18-month-old, female, LongEvans rat (Rattus norvegicus).

The investigator noticed a large, firm, subcutaneous mass in the right axilla.

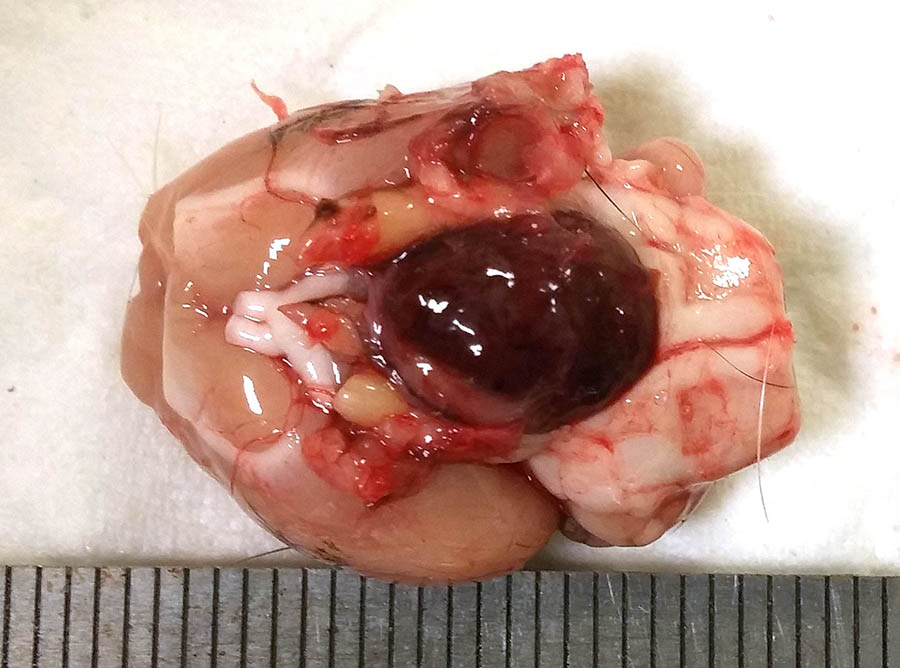

Gross Description:

At necropsy, a firm, circumscribed and lobulated subcutaneous mass approximately 3.5 cm in diameter, was attached to the skin in the axillary area. On removing the brain, a dark red-brown nodular mass, approximately 1 cm in diameter, was present in the ventral aspect of the brain, replacing the pituitary gland.

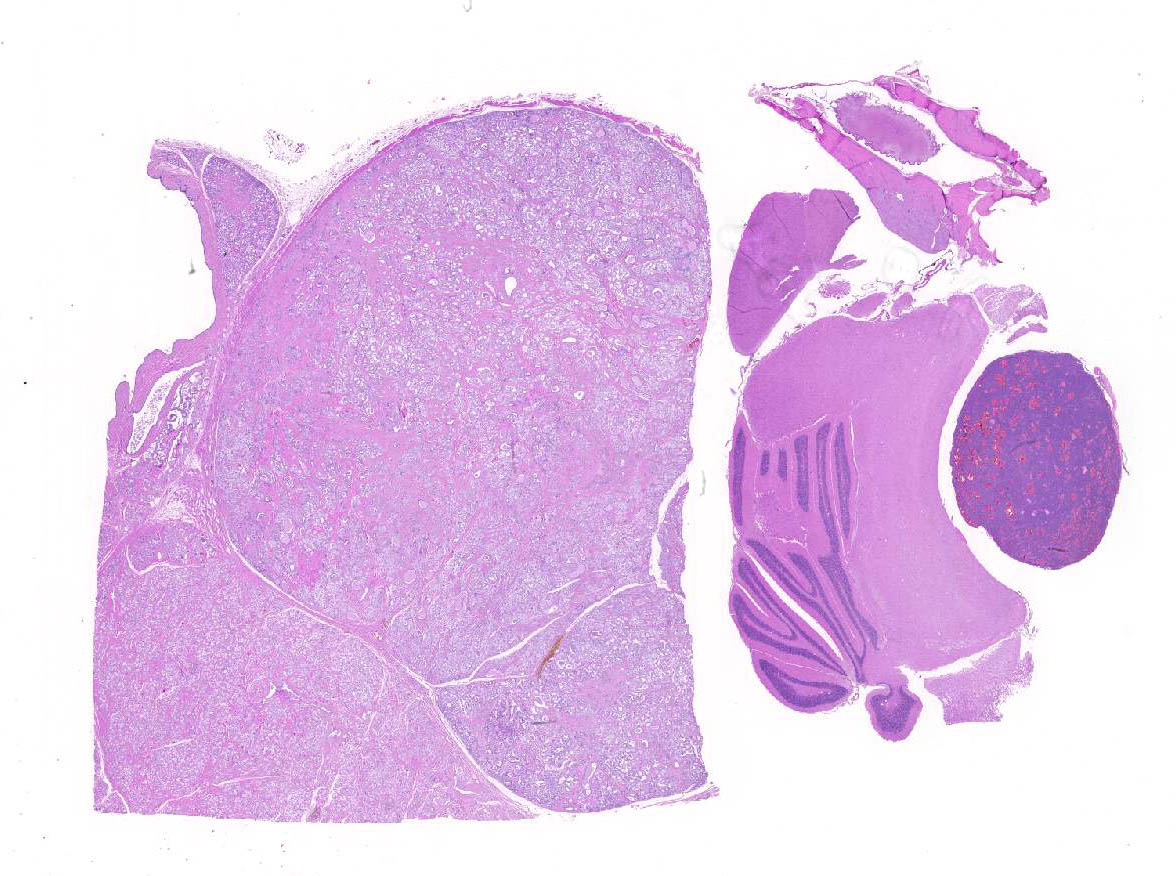

Histopathologic Description:

Axillary mass - Part of a multilobular mass composed of disorganized epithelial pro-liferation and connective tissue. The neoplastic epithelium forms variably sized acini and tubuli which are aggregated into lobules dissected and separated by moderate to abundant dense, collagen-rich, connective tissue. The neoplastic cells are cuboidal to irregular and arranged as a monolayer; they have moderate to abundant cytoplasm which is often vacuolated.

Vacuoles vary from numerous and small (microvesicular vac-uolation) to large, single, lipid vacuoles which lead to significant expansion of the cytoplasm and peripheral displacement of the nucleus. Nuclei are round to slightly irregular, vesicular to finely granular, and have a small nucleolus. There is slight anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Mitotic fi-gures are not observed.

Multifocally, the lumen of acini contains proteinaceous secretory material, which in some cases shows internal layers (corpora amylacea). In other parts of the mass, not submitted, there are large cysts filled with secretory material and lined by epithelial cells as described. Pituitary mass- Compressing the medulla there is a small, discrete, thinly encapsulated and densely cellular nodular mass composed of a uniform population of polygonal cells arranged into solid islands separated by fine fibrovascular stoma.

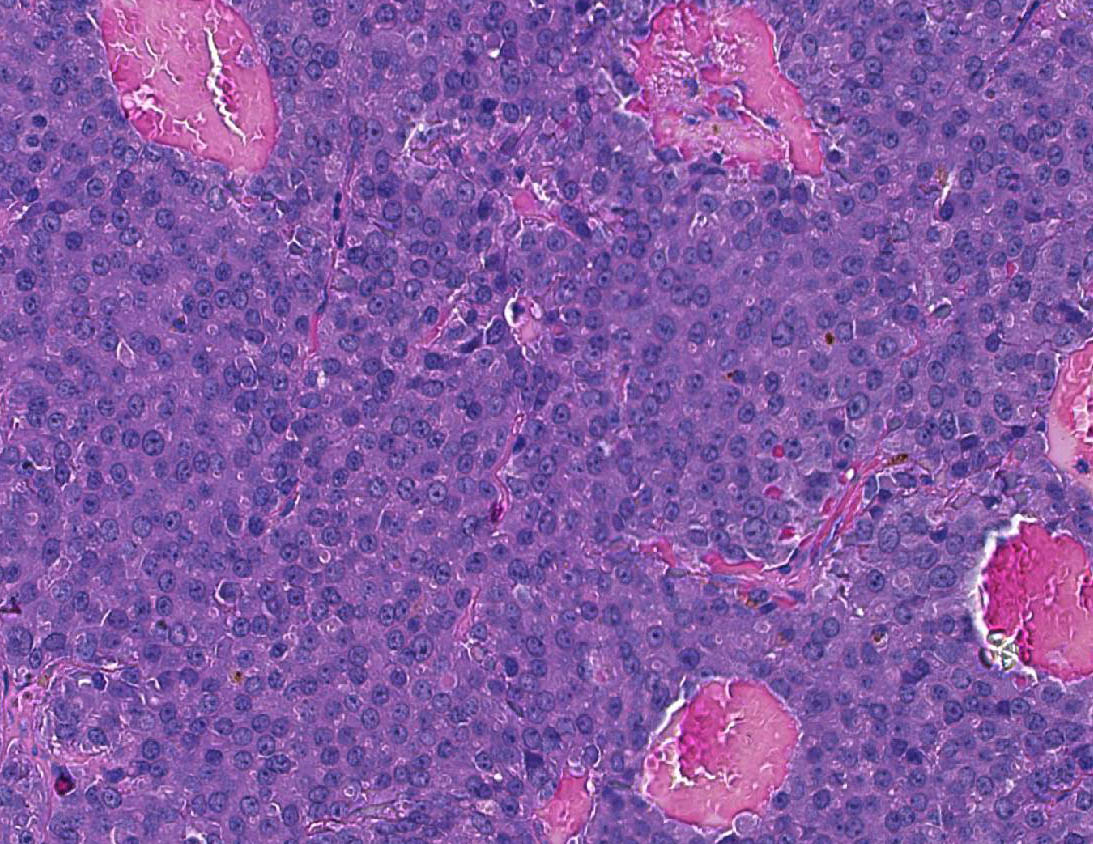

The neoplastic cells have a moderate amount of eosinophilic to lightly amphophilic cytoplasm, relatively indistinct cytoplasmic margins, and round to slightly irregular, vesicular to finely granular nuclei with a small nucleolus. There is anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. A few mitotic figures are observed. At the edge of the mass there are scattered giant ka-ryomegalic cells. There are numerous large, blood-filled spaces lined by neoplastic pituitary cells.

At one edge of the mass there are possible remnants of the pre-existing adeno-hypophsis

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Axillary mass: Mammary gland fibro-adenoma

Pituitary gland (adenohypophysis): Adenoma

Lab Results:

None.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Mammary fibroadenoma: Mammary tumors are one of the most common tumors in old female rats,1 especially in the SD strain where the incidence of spontaneous tumors often approaches 50% in lifetime studies of control animals.4 Most are benign fib-roadenoma which are composed of mammary epithelial cells and connective tissue.4 The incidence of these tumors varies considerably between different rat strains, suggesting that genetic background is an important factor in their development. Other factors which influence their occurrence are diet, environment, and in the case of toxiclogic studies, the degree of differentiation of the mammary glands, and physiologic and hormonal status at the time of chemical exposure.4

Mammary tumors are rare before 1 year of age, and are generally found after 18 months of age.1 Mammary fibroadenomas also occur occasionally in male rats.5

Histologically, the proportion of glandular and connective tissue in fibroadenomas is variable, and this has led to their sub-classification. However, since several subtypes are commonly encountered in a single tumor, this division appears to be of little merit.1, 4 Exposure to estrogen and prolonged exposure to prolactin increase tumor frequency, whereas parity and ovariectomy decrease the incidence of mammary gland tumors in rats.1,5 Although increased mammary gland tumors are found in rats with pituitary tumors and high levels of prolactin are considered a contributing factor, a casual effect is difficult to determine.1,5 Estrogens induce both pituitary and mammary tumors, and the incidence of both types of tumors correlates with body weight.1

Mammary fibroadenomas may become very large, but as a rule, they are only locally infiltrative and rarely metastasize. Surgical excision is possible in pet rats or experimentally valuable animals.5 Sp-ontaneous mammary adenocarcinomas are most common in SD rats and uncommon in other strains. They may develop in existing fibroadenoma, but this is rare. They generally do not metastasize.1

Pituitary adenoma is very common in older rats, especially of the Wistar strain. There is conflicting information in standard ref-erences regarding their incidence in other strains: according to Boorman and Everitt 1 they are common in F344 and uncommon in SD, while according to Percy and Barthold 5 they are common in the SD strain. Some studies suggest a slightly higher incidence in females. Other than age, genetic ba-ckground, diet, and breeding history are thought to play a role in tumor development. Reduction of food intake reduces their incidence and, according to one study, mated females are less prone to these tumors than virgin females.5 Clinical signs vary from asymptomatic to severe depression, often with incoordination.5 The neurologic signs are due to compression of the brain.

Histologically, the hallmark of adenoma is compression of the surrounding parenchyma and sharp delineation at the margins of the nodule. The neoplastic cells are generally larger than normal and have more abundant cytoplasm, which is usually pale or faintly basophilic. The mitotic index is usually low. Often, there are prominently dilated vascular channels which may be lined by endothelial cells or neoplastic pituitary cells; this has been referred to as angiomatous or cavernous pattern. Giant cells and areas of necrosis may be present.3 Most pituitary tumors are thought to arise from the pars distalis and are diagnosed as chromophobe adenomas based on HE-stained sections.1,5 Acidophil and basophil tumors have also been described. The diagnosis of chromophobe adenoma pro-vides no information regarding the endocrine status of the tumor.1 In pituitary tumors studied by immunocytochemistry, prolactin-producing tumors are the most common type,5 but growth hormone, ACTH, TSH and FSH-secreting tumors have also been described.1 Lactation in an aging rat is often a sign of a functional pituitary tumor.1

Pituitary adenomas should be differentiated from hyperplastic and hypertrophic lesions. In hyperplastic lesions there is proliferation of cells of normal size, no evidence of pseudocapsule formation, and no significant compression of adjacent pituitary tissue. Nodules of hypertrophic cells form islands of large cells without evidence of encapsulation.1,3 Pituitary carcinomas are rare and require evidence of invasion or distant metastasis for their diagnosis.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Pituitary gland: Pituitary pars distalis adenoma.

2. Mammary gland: Mammary fibro-adenoma.

Conference Comment:

Mammary gland fibroadenoma is one of the most common rat mammary tumors. It is more commonly seen in female rats and has an especially high incidence in Sprague Dawley rats as mentioned above. It is generally well def-ined and composed of proliferating glandular tissue surrounded by a pro-liferation of fibrous tissue. Large sections or an entire mammary gland may be involved.

It may have a lobular growth pattern with variation in size and composition of individual lobules. Secretory epithelium is arranged in a single layer, and small foci of pleomorphic cells may be present, but mitoses are uncommon. It is differentiated from adenoma by the conspicuous con-tribution of a fibrous connective tissue component.

Adenocarcinoma may arise fr-om within mammary fibroadenoma.6 Other less common mammary neoplasms in the rat include ductular carcinoma and cy-stadenoma. Another lesion which must be differentiated from benign mammary neoplasia is lob-uloalveolar hyperplasia. This condition may be referred to as pseudopregnancy, and is differentiated from neoplasia by maintaining the normal lobular histologic architecture, specifically the relationships among the various mammary tissue components in-cluding ducts, glandular epithelium, stroma, and myoepithelium.

Cellular pleomorphism is absent; however, focal squamous met-aplasia can occur and hyperplastic lesions may be focal or diffuse.6 Diffuse mammary hyperplasia is associated with hormonally-induced physiologic changes during late gestation and lactation. Focal hyperplasia may be accompanied by fibrous pro-liferation separating acini, but the lobular architecture is maintained and the lesion is not compressive, which aids in dif-ferentiating it from mammary fibro-adenoma.6

Dietary food restriction is known to decrease the incidence of both pituitary and mam-mary tumors in rats. Lower levels of prolactin are present in rats on a restricted diet, and prolactin is a primary stimulus for the development of mammary neoplasia in rats. Most rat pituitary neoplasms are prolactin-immunopositive and are postulated to be involved in the development of mammary tumors,2 although a definitive link has not been demonstrated in all cases. Furthermore, not all rat pituitary tumors are prolactin positive.

Interestingly, reduction in body weight from decreased caloric intake is paradoxically associated with an increase in uterine neoplasia in rats; this effect is postulated to be related to prolactins influence on function of the ovary and corpora lutea. In the rat prolactin promotes progesterone production in the corpus luteum post ovulation, which opposes estrogens promotion of uterine growth. Therefore, a decrease in prolactin results in elevated levels of estrogen, which stimulates endometrial growth.2

Long term administration of estrogen to rats also results in prolactin producing pituitary adenomas. These induced tumors may also produce other hormones, such as thyroid stimulating hormone.7

References:

1. Boorman GA, Everitt JI. Neoplastic disease.In: Suckow MA, Weisbroth SH, Franklin CL, eds. The Laboratory Rat. 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press; 2006:493-4, 501-2.

2. Harleman JH, Hargreaves A, Andersson H, Kirk S.A review of the incidence and coincidence of uterine and mammary tumors in Wistar and Sprague-Dawley rats based on the RITA database and the role of prolactin. Toxicol Pathol. 2012; 40: 926-930.

3. Majka JA, Sollveled HA, Barthel CH, Van Zwiten MJ. Proliferative lesions of the pituitary in rats, E-2. In: Guides for Toxicological Pathology. Washington DC: STP/ARP/AFIP; 1990.

4. Mann PC, Boorman GA, LoIIioi LO, McMartin DN, Goodman DG. Proliferative lesions of the mammary gland in rats IS-2. In: Guides for Toxicological pathology.Washington DC: STP/ARP/AFIP; 1996.

5. Percy DH, Barthold SW.Pathology of laboratory rodents. 3rd ed. Ames IA:Blackwell Publishing; 2007:171-174.

6. Rudmann D, Cardiff R, Chouinard L, Goodman D, Kuttler K, Marxfeld H, et al.: Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse mammary, Zymbal's, preputial, and clitoral glands. Toxicol Pathol 2012:40(6 Suppl):7S-39S.

7. Takekoshi S, Yasui Y, Inomoto C, Kitatani K.A histopathological study of multi-hormone producing proliferative lesions in estrogen-induced rat pituitary prolactinoma. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2014; 47(4):155-164.