Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 10

4 November 1998

- Conference Moderator:

Dr. Georgina Miller

NCRR LSS SSB, Bldg. 28A, Room 117

28 Library Drive, MSC 5210

Bethesda, MD 20892-5210

NOTE: Click on images for larger views. Use

browser's "Back" button to return to this page.

Return to WSC Case Menu

- Case I - RT97-1153 (AFIP 2639047)

Signalment: Adult, female, Spontaneous Hypertensive Rat

(SHR).

-

- History: This animal was submitted due to a history

of anorexia and abnormal breathing. It was used in a hypertension

study and was euthanized with CO2.

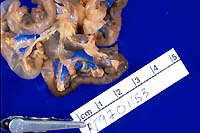

Gross Pathology: The rat was moderately dehydrated and

thin with diffuse skeletal muscle atrophy and little abdominal

body fat. Moderate dehydration was evident. The urinary bladder

was devoid of urine; testing of residual urine on the mucosa

revealed moderate to high ketonuria and trace glycosuria. The

walls of mesenteric vessels throughout the gastrointestinal tract

were thickened and formed 1-3 mm diameter reddish purple nodules.

Other major organs appeared normal.

- Case 10-1. Gross photos (see paragraph above)

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

- Morphologic Diagnosis: Mesenteric arteries/arterioles

- arteriopathy with smooth muscle hypertrophy and thrombosis.

- Etiologic diagnosis: Hypertensive arteriopathy/arteriolopathy.

-

- The rat had multiple organ abnormalities secondary to vascular

disease, consistent with hypertension. Arteriolar changes in

the myocardium included medial hypertrophy and medial fibrinoid

degeneration. Mesenteric and pancreatic arteries and arterioles

were prominently dilated, tortuous, and had subintimal proliferation

and medial hypertrophy, with mild to variable amounts of chronic

perivascular inflammation. Many of the vessels were partially

to completely occluded by thrombi. There were increased numbers

of blood vessels of varying size within the mesentery. Pulmonary

edema was present, along with increased numbers of alveolar macrophages

and erthyrophagocytosis, consistent with chronic congestive heart

failure. One adrenal gland and a section of small intestine were

infarcted secondary to vascular compromise. Renal abnormalities

included medial hypertrophy and intimal proliferation of arterioles,

multifocal glomerulosclerosis, and associated tubular ectasia

with proteinaceous fluid. The predominant findings in this case

are consistent with vascular disease and related sequelae secondary

to hypertension.

-

- The enlarged and tortuous mesenteric arteries demonstrate

a number of changes associated with hypertension. In some areas,

the endothelial lining appears relatively normal whereas in other

regions, the endothelium is necrotic with fibrin deposition and

thrombi formation. Most of the thickening of the arteries is

in the tunica media, and enlarged myocytes with enlarged nuclei

are clearly seen in the smooth muscle indicating hypertrophy.

In some areas, a discrete border is lacking between the muscle

cells and adventitial fibroblasts. The adventitial layer is distended

due to increased collagen deposition. Hemorrhage and hemosiderin

deposits are present. There is an inflammatory reaction consisting

predominately of neutrophils in both the media and the adventitia.

Affected arterioles are evident in both the muscularis and submucosa

of the intestine. Some arterioles have a narrowed lumen with

characteristic "onion skinning". Based on gross morphology,

the principal differential diagnosis is polyarteritis nodosa,

a generalized immune-complex disease. In rats with polyarteritis,

vascular lesions are commonly found in mesenteric arteries and

their branches, but muscular arteries in any organ may be involved.

Grossly, the arteries are tortuous and often exhibit thrombosis

or occlusion.

-

- The spontaneous hypertensive rat (SHR) was first developed

in 1963 from outbred Wistar Kyoto rats by Okamoto and Aoki to

develop an animal model for hypertension. The strain has been

successful in that 100% of the rats develop spontaneous hypertension.

Long term hypertension is known to cause severe arterial disease

which can result in hemorrhage, infarction and nephrosclerosis.

The arterioles in spontaneous hypertensive rats show a thickening

of the tunica media consistent with periarteritis nodosa, and

the structural adaptation of the vessels occurs in response to

an increased pressure load.

-

- In severe hypertensive animals, arteries progress through

a number of phases based on the age of animal and the degree

of blood pressure elevation. Arteries with a diameter of less

than 300 mm determine pressure resistance. In hypertension, pressure

resistance is elevated, implying a narrowing of vasculature.

The mesenteric artery of SHR has a 16% smaller luminal diameter

and a 49% thicker media than nonhypertensive rats. Blood pressure

increases steadily after 6 weeks of age in SHR, rising from 170

mmHg to around 200 mmHg and finally reaching over 250 mmHg by

death. The arteries go through phases beginning with a prehypertensive

period to eventually irreversible damage. During the prehypertensive

phase, the surface of the internal elastic lamina becomes irregular,

then the elastic lamina is destroyed, and modified medial smooth

muscle cells appear. Finally, the internal and medial elastic

lamina are both completely destroyed and small fragments of the

laminae are all that remain.

-

- Before six weeks of age, mesenteric arterial smooth muscle

cells appear morphologically normal with blood pressure around

170 mmHg. After 6 to 7 weeks, the innermost medial smooth muscle

cells begin to show alterations of shape because of an increase

of cell organelles. The prominent morphological changes include

a marked increase and dilatation of rough endoplasmic reticulum

containing electron-dense material. By around 13 weeks of age,

blood pressure has increased to around 210 mmHg and the smooth

muscle cells of the mesenteric arteries show greater change.

The shape of the smooth muscle cell is irregular and few organelles

are seen in the cytoplasm. The internal elastic lamina and the

medial smooth muscle cells begin to interact via plasma membrane

protrusions from the muscle cells. The shape of the smooth muscle

cell is extremely irregular in the middle layer of the media.

Once blood pressure has increased to over 240 mmHg, the rat has

reached advanced stages of hypertension. This usually occurs

by week 28 and there are marked degenerative and degradative

changes in the smooth muscle cells, especially in the inner media.

Prominent protrusions of the plasma membrane extend to the internal

elastic lamina and elastic fiber becomes fragmented, indicating

destruction of the internal elastic lamina by smooth muscle cells.

Commonly, medial smooth muscle cells will migrate into the subintimal

region. By the final stage of hypertension, the internal elastic

lamina appears fragmented and the media is thickened.

-

- Thickening of the arterial wall in chronic hypertension is

thought to be the result of both hypertrophy and hyperplasia

of the medial smooth muscle cell, although the degree of each

differs based on the type of artery: elastic, muscular, or arteriolar.

For example, both hypertrophy and hyperplasia contribute to wall

thickening in muscular arteries, but arteriolar vessels show

a greater amount of hyperplasia. It has been suggested that hyperplasia

is a very early event which reaches its maximum even while blood

pressure is submaximal. The degree and duration of hypertension

determines which is predominant.

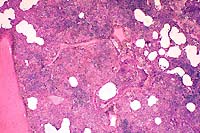

2x

obj

2x

obj

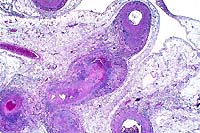

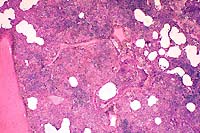

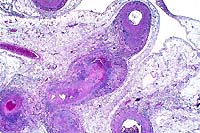

- Case 10-1. Mesentery. There is medial hypertrophy

and inflammatory infiltrates around the affected vessels. Some

arteries have fibrinoid degeneration and/or thrombi in arterial

lumens. Perivascular mesenteric fat contains high numbers of

inflammatory cells (steatitis).

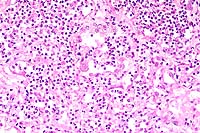

20x

obj

20x

obj

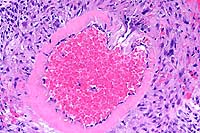

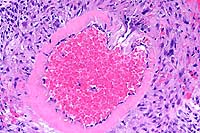

- Case 10-1. Mesenteric artery. There is extensive fibrinoid

degeneration of the vessel and moderate perivascular infiltrates

of lymphocytes and macrophages.

-

- AFIP Diagnoses:

- 1. Mesentery, arteries: Arteriopathy, characterized by fibrosis,

medial hypertrophy, fibrinoid change, thrombosis and chronic-active

arteritis, spontaneous hypertensive rat (SHR), rodent.

2. Mesenteric adipose tissue: Steatitis, chronic-active, diffuse,

mild.

-

- Conference Note: The pathogenesis of the vascular

changes occurring in spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHR) has

been well described by the contributor. Interestingly, the anatomical

locations, gross appearance, and histomorphology of the lesions

in SHR are very similar to those of polyarteritis (periarteritis)

nodosa (PAN). As mentioned by the contributor, the vascular lesions

attributed to hypertension in SHR develop early (6 to 7 weeks)

and progress with age. The severity and distribution of affected

arteries is greater in SHR males than in females. Clinically,

polyarteritis nodosa tends to occur in aged rats (reports vary

between 498 and 900 days), and the incidence is higher in males

than females. The lesions of PAN are often found incidentally

at necropsy. PAN is believed to be an immune-mediated disease.

-

- In the absence of history and signalment, differentiating

the histologic changes of PAN and those developing in SHR can

be problematic. The microscopic vascular lesions that occur in

SHR have been characterized and sequenced by the contributor.

PAN is classically described as necrotizing vasculitis and fibrinoid

necrosis affecting small and medium-sized vessels of multiple

organ systems. In the acute phase, the vasculitis is characterized

by transmural infiltration of the vascular wall by high numbers

of neutrophils, eosinophils, and mononuclear cells with fibrinoid

necrosis of the inner half of the vessel. At later stages, the

acute inflammatory infiltrate disappears and is replaced by fibrous

thickening of the vessel wall accompanied by a mononuclear cell

infiltrate13. A characteristic finding in PAN is the presence

of unaffected and severely affected blood vessels within the

same tissues, as well as segmental lesions along individual blood

vessels14. Subjectively, the vascular lesions in PAN seem to

be characterized by higher numbers of inflammatory cells that

are more disruptive to the vessel walls compared to the arterial

changes in SHR.

-

- In this case, in some sections of the small intestine, arterioles

within the lamina propria and tunica muscularis are characterized

by concentric, laminated thickening of the vessel wall, which

narrows or occludes the lumen, consistent with "onion-skinning"

as noted by the contributor. Though hypertension may be a complication

in humans suffering from PAN, the microscopic feature of "onion

skinning" with luminal obliteration in this rat is characteristic

of hyperplastic arteriolosclerosis. Hyperplastic arteriolosclerosis

is more consistent with hypertension than an immune-mediated

etiology.

-

- Contributor: Pathology Unit, Laboratory Sciences Section,

Veterinary Resources Program, NCRR, National Institute of Health,

9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892.

-

- References:

- 1. Black MJ, et al.: Vascular growth responses in SHR and

WKY during development of renal hypertension. Amer J Hypertension

10:43-50, 1997.

- 2. Dominiczak AF, et al.: Vascular smooth muscle polyploidy

and cardiac hypertrophy in genetic hypertension. Hypertension

27:752-759, 1996.

- 3. McGuffee LJ, Little SA: Tunica media remodeling in mesenteric

arteries of hypertensive rats. Anatomical Record 246:279-292,

1996.

- 4. Dilley RJ, Kanellakis P, Oddie CJ, Bobik A: Vascular hypertrophy

in renal hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension

24:8-15, 1994.

- 5. Ganten D, de Jong W: Experimental and genetic models of

hypertension, In: Handbook of Hypertension, vol. 16, Elsevier

Science B.V., Amsterdam, Holland, 1994.

- 6. Ito H: Pathophysiological changes of the membrane system

of the arterial smooth muscle cells. In: Membrane Abnormalities

in Hypertension, Kwan CY ed., vol. 2, pp. 2-21, CRC Press Inc.,

Boca-Raton, Florida, 1989.

- 7. Lee RMKW: In: Blood Vessel Changes in Hypertension: Structure

and Function, vol. 1, pp. 2-17, CRC press Inc., Boca-Raton, Florida,

1989.

- 8. Lee RMKW, Forrest JB, Garfield RE, Daniel EE: Ultrastructural

changes in mesenteric arteries from spontaneously hypertensive

rats. Blood Vessels 20:72-91, 1983.

- 9. Cox, R: Basis for the altered arterial wall mechanics

in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 3:485-495,

1981.

- 10. Andrews EJ, Ward BC, Altman NH: In: Spontaneous Animal

Models of Human Disease, vol. 1, pp. 51-54, Academic Press, New

York, 1979.

- 11. Baker HJ, Lindsey JR, Weisbroth S: In: The Laboratory

Rat: Volume I Biology and Diseases, pp. 63-72, Academic Press,

Inc., New York, 1979.

- 12. Benirschke K, Garner FM, Jones TC: In: Pathology of Laboratory

Animals, vol. 2, pp. 2018-2055, Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.,

New York, 1978.

- 13. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T: Blood vessels. In: Robbins

Pathologic Basis of Disease, 6th ed., pp. 510-522, WB Saunders,

Philadelphia, PA, 1999.

- 14. Snyder PW, et al.: Pathologic features of naturally occurring

juvenile polyarteritis in beagle dogs. Vet Path 32:337-345, 1995.

- 15. Anver MR, Cohen BJ: Lesions associated with aging. In:

The Laboratory Rat Volume I Biology and Disease, Baker HJ, Lindsey

JR, Weisbroth SH eds., pp. 383-384, Academic Press Inc., New

York, New York, 1979.

- 16. Wexler BC, McMurtry JP, Iams SG: Histopathologic changes

in male vs female spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Gerontol

36:514-519, 1981.

- 17. Suzuki T, Oboshi S, Sato R: Periarteritis nodosa in spontaneously

hypertensive rats - incidence and distribution. Acta Pathol Jpn

29:697-703, 1979.

-

- Case II - Vn-72-98 (AFIP 2642410)

-

- Signalment: One-year-old, male, guinea pig (Cavia

porcellus).

-

- History: This is one of five guinea-pigs which were

raised as pets in a household. The owner brought the animal to

the attention of a veterinary practitioner because of "growths"

on its ears that had been present for almost five months. The

animal was otherwise normal. A decision was made to euthanatize

the guinea-pig, and it was submitted to our lab for necropsy.

Gross Pathology: The pinna of the right ear was irregularly

swollen and alopecic, and the overlying skin of the dorsum of

the pinna was bright red, ulcerated and covered by crusts (color

transparency). At the base of the left ear there was a gray,

firm, alopecic nodule measuring 1.5 cm in diameter. Other organs

were unremarkable.

- Case 10-2. Gross photo (see description above)

-

- Laboratory Results: None.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Skin of the

ear: Dermatitis and panniculitis, granulomatous, focally extensive,

moderate to severe, with intracytoplasmic protozoal amastigotes

within macrophages, etiology consistent with Leishmania sp. (cutaneous

leishmaniasis), guinea-pig (Cavia porcellus).

-

- Leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease caused by many pathogenic

species and variously named subspecies of the genus Leishmania

(order Kinetoplastida, family Trypanosomatidae). Differentiation

among species cannot be made based only on their morphological

aspects in tissue sections. Differentiation is based on clinical

signs and pathological changes, morphological aspects and behavior

of the parasite, and on specific laboratory tests (e.g., serology,

immunohistochemistry, indirect immunofluorescence).

-

- Leishmania spp. occur in two parasite forms. The intracellular

amastigotes (found in parasitophorous vacuoles within macrophages

of the vertebrate host) and the promastigote (found predominantly

in the sandfly vector). The amastigotes are spherical, 2.5 to

5 mm, have a prominent, eccentric nucleus, and a transversely

oriented kinetoplast.

-

- Diseases caused by Leishmania sp. are transmitted by hematophagous

sandflies which include the genera Lutzomyia sp. (in the New

World) and Phlebotomus (in the Old World). When the insect vector

takes a blood meal, it becomes infected by ingestion of infected

macrophages containing amastigotes. These are released from the

macrophages in the midgut of the insect and transform into promastigotes

(10-20 mm in length). The insect vectors then take another blood

meal and, in doing so, infect the next mammalian host. There

is usually a primary reservoir host for a given Leishmania species

in a particular area where the parasite is maintained in a cycle

between the insect and the vertebrate host.

-

- Clinically and epidemiologically, the disease can be divided

into three main forms caused by different species of Leishmania.

Dermal cutaneous leishmaniasis (L. tropica, L. major), visceral

leishmaniasis (L. donovani), and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

(L. braziliensis, L. mexicana). The lesions of the case described

here are restricted to the dermis and subcutis and are characterized

by marked proliferation of epithelioid macrophages and moderate

amounts of fibrovascular tissue. Most of these macrophages contain

phagocytized amastigotes with morphology consistent with Leishmania

sp. The large numbers of parasites observed in these sections,

although not a consistent finding in leishmaniasis, has been

described previously.

-

- Histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and trypanosomiasis

should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A kinetoplast

and a small nucleus can be identified in Leishmania organisms

in tissue sections. These structures are absent in the causative

organisms of the first three diseases. The tissue phase of Trypanosoma

cruzi has a kinetoplast, but the distribution and type of lesions

in trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) differ from those found in

leishmaniasis.

4x obj

4x obj

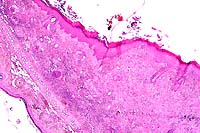

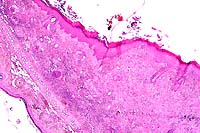

- Case 10-2. Ear. The dermis is expanded by large numbers

of macrophages and lymphocytes.

40x

obj, Giemsa

40x

obj, Giemsa

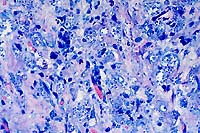

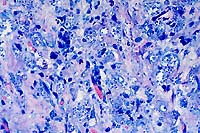

- Case 10-2. Leishmanial amastigotes appear as oval

3-5u basophilic structures surrounded by clear halos.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin, auricular: Dermatitis,

histiocytic and lymphoplasmacytic, diffuse, severe, with ulceration,

serocellular and hemorrhagic crust, and numerous intrahistiocytic

protozoal amastigotes, guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), rodent.

-

- Conference Note: Most conference participants preferred

the morphologic diagnosis of histiocytic and lymphoplasmacytic

dermatitis rather than granulomatous dermatitis because of the

lack of multinucleate macrophages and activated epithelioid macrophages

(macrophages with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large,

vesiculate nuclei containing prominent nucleoli), the histologic

hallmarks of granulomatous inflammation.

-

- Leishmania amastigotes are the only protozoa that survive

and replicate in the macrophage phagolysosome. After phagocytosis

of the promastigotes by macrophages, the acidity in the phagolysosome

induces them to transform into amastigotes. The amastigotes are

protected from lysosomal acid by a proton-transporting ATP-ase

which maintains the intracellular pH of the parasite at 6.5.

Additionally, leishmanial organisms have on their surface two

glycoconjugates which appear to be important virulence factors.

Lipophosphoglycans are glycolipids that form a dense glycocalyx

and bind to C3b and iC3b. Organisms resist lysis by complement

C5-C9, and are phagocytosed by macrophages through complement

receptors CR1 (LFA-1) and CR3 (Mac-1)6. Lipophosphoglycans may

also serve to protect amastigotes by inhibiting lysosomal enzymes

and scavenging oxygen free radicals. The second glycoconjugate,

gp63, is a zinc-dependent metalloproteinase that cleaves complement

and some lysosomal enzymes.

-

- Conference participants briefly discussed the predisposition

for development of cutaneous lesions on the ears in several reports

of leishmaniasis in various animals. The skin of the face and

the ears are most exposed to the environment, and may predispose

these areas on hosts to inoculation by the sandfly vector. Another

explanation for the predilection of lesions at these anatomical

sites may be related to temperature. Leishmania sp. that cause

visceral disease grow at 37°C in vitro, while those that

cause mucocutaneous disease, grow only at 34°C6. The tips

of the ears are probably cooler than other areas of skin.

-

- Like the contributor, participants considered a similar differential

diagnosis for this cutaneous lesion based upon the character

of the inflammation, the presence of intrahistiocytic organisms,

and organism morphology. In tissue sections, leishmanial amastigotes

are spherical to ovoid and measure 2 by 5mm. Each amastigote

contains a round, eccentric nucleus and rod-shaped kinetoplast

that lies perpendicular to the nucleus; both structures are basophilic

in hematoxylin and eosin stained sections; in Giemsa-stained

sections the nucleus is red.

-

- In contrast, the kinetoplast of Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes

is found parallel to the nucleus, and is larger and more basophilic

than that of Leishmania. Histoplasma organisms, also typically

found within macrophages, are similar in size to Leishmania and

may illicit an intense histiocytic to granulomatous response;

however, the yeasts lack a kinetoplast and are stained by the

PAS and GMS methods. Blastomyces dermatitidis, usually found

as a spherical yeast measuring between 7-15mm with a double-contoured

cell wall, is found both within macrophages and extracellularly;

the organism is characterized by single, broad base budding and

stains with GMS and PAS. Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum

tachyzoites may be round, oval, or crescent-shaped, measure between

4 to 6mm, contain a basophilic nucleus, and lack a kinetoplast.

Tachyzoites may be found within a variety of host cells, including

leukocytes, endothelial cells, stromal cells, and epithelial

cells.

-

- Contributor: Universidade Federal de Santa Maria,

Departamento de Patologia, 97105-900, Santa Maria RS, Brazil.

-

- References:

- 1. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by protozoa.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 549-600, Williams and

Wilkins, Baltimore, 1997.

- 2. Ramos-Vara JA, Ortiz-Santiago B, Segalès J, Dunstan

RW: Cutaneous leishmaniasis in two horses. Vet Pathol 33:731-734,

1996.

- 3. van der Lugt JJ, Stewart CG: Leishmaniasis. In: Infectious

Diseases of Livestock with Special Reference to Southern Africa,

Coetzer JAW, Thomson GR, Tustin RC eds., vol.1, pp. 269-272,

Oxford, Cape Town, South Africa, 1994.

- 4. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: Sarcomastigophora. In:

An Atlas of Protozoal Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed., pp.

3-10, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, 1998.

- 5. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: Apicomplexa. In: An Atlas

of Protozoal Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed., pp. 53-60,

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, 1998.

- 6. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T: Infectious diseases. In:

Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 6th ed., pp. 391-392, WB

Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1999.

- 7. Yager JA, Wilcock BP: Nodular and/or diffuse dermatitis.

In: Color Atlas of Surgical Pathology of the Dog and Cat, pp.

119-130, Wolfe Publishing, London, England, 1994.

-

-

- Case III - 97N0525 (AFIP 2642200)

-

- Signalment: 2½-year-old, Walker hound, male,

canine.

-

- History: This dog was one of a litter of three puppies

raised together as a hunting group. Animals were kept in an outdoor

kennel year round and were current on vaccinations. Each animal

developed ulcerated hind limb digital pads and was treated for

bacterial infections with systemic antibiotics, local debridement,

and hydrotherapy. This dog had a digit amputated due to the severity

of the ulceration that had progressed to gangrene. One of the

other littermates died and was not necropsied. This dog became

severely dyspneic and anorexic and was presented in lateral recumbency.

The dog died despite fluid therapy, intravenous broad-spectrum

antibiotics, and steroids. The surviving dog seemed to improve

with systemic gentamycin and topical therapy of the toes.

-

- Gross Pathology: A 25 pound (11.3 kg), adult, male,

black and tan Walker hound was presented for necropsy. The dog

was in adequate nutritional status and had mild autolysis. The

right rear footpad had sloughed, and the caudal tarsus had a

two centimeter diameter ulcer of the plantar surface above the

footpad. The toenail of the second digit was missing. The liver

was enlarged and had an accentuated lobular pattern. Both kidneys

had several wedge-shaped depressions characteristic of chronic

infarcts. The right cranial and caudal lung lobe vessels each

contained 15 or more nematodes typical of Dirofilaria immitis.

The main pulmonary artery had more than 15 adult worms. The left

and right cardiac ventricles were enlarged; the chambers were

dilated and the free walls were thickened. The mitral and tricuspid

valve leaflets were thickened and irregular. The femoral, saphenous,

and tarsal veins and arteries contained adult nematodes. All

lymph nodes seen were enlarged and dark red. Both testes were

firm, small, and intraabdominal. The prostate gland was very

small.

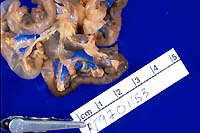

- Case 10-3. Tarsal region. The metatarsal pad is necrotic

and covered with a brown exudate which contains a pale tan nematode

parasite.

-

- Laboratory Results: A mixed population of bacteria

grew from a culture of the right hind footpad.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Tarsal and carpal

vessels: Inflammation, perivascular, focal, mild, chronic, with

adult filarial nematodes in perivascular tissue and in arteries.

-

- Etiology: Dirofilaria immitis.

- It is unusual even in endemic areas to see Dirofilaria immitis

adults in the systemic arteries and in tissues. This dog and

its littermates had never received heartworm preventive treatment

and had overwhelming infections. The adult heartworms in the

arteries of the distal limbs led to inflammation and blockage

of the vessels with impedance of blood flow. This created the

appropriate environment for gangrene.

2x

obj

2x

obj 10x

obj

10x

obj

- Case 10-3. Fibroelastic artery. There are cross sections

of two nematodes within a large artery. The 10x view shows two

empty uteri and a smaller gut in the pseudocoelom. There is a

coelomyarian musculature on either side of two large flattened

lateral cords (top & bottom center). Portions of a fibrin

thrombus and the arterial wall are in the lower right corner.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Subcutis, fibroelastic arteries: Arteritis,

chronic-active, focally extensive, moderate, with periarteritis,

fibrin thrombus, and intraluminal adult nematode parasite, Walker

hound, canine, etiology consistent with Dirofilaria immitis.

-

- Conference Note: This case was studied in consultation

with Dr. C.H. Gardiner, parasitology consultant to the Department

of Veterinary Pathology. Morphologically, this adult nematode

parasite is characterized by a cuticle with lateral internal

ridges that project into hypodermal chords, coelomyarian, polymyarian

musculature which is divided by the flattened hypodermal chords,

and a pseudocoelom which contains an intestine with small lumen

and two reproductive tubes (uteri). In some sections, the uteri

contain sperm, indicating that copulation had occurred.

-

- Aberrantly located adult heartworms have been infrequently

reported in dogs since the middle of the 19th century. Reported

sites include the eyes, subcutaneous interdigital cysts, intramuscular

cysts and abscesses, peritoneal cavity, bronchioles, in a salivary

gland mucocele, and the central nervous system including the

lateral ventricles and the epidural space. Clinical signs observed

in dogs with systemic arterial dirofilariasis include lameness,

weakness, poor peripheral perfusion, paresthesia of the hindlimbs,

and ischemic necrosis of tissues such as muscle and digits due

to thromboembolic disease.

-

- Systemic arterial dirofilariasis is an uncommon condition,

and the pathogenesis is not completely understood. In some reported

cases, migration of parasites was thought to have occurred from

the right ventricle through an identified ventricular septal

defect, patent ductus arterious, or a patent foramen ovale after

development of high right heart pressures and pulmonary hypertension.

In other cases, no congenital cardiovascular defect was identified

during necropsy. In these cases, the condition may have occurred

due to aberrant migration or development of L5 heartworms within

the systemic arterial circulation. While the mechanism of systemic

arterial dirofilariasis is not understood, the presence of adult

worms in the abdominal aorta may manifest as thromboembolic disease

with subsequent infarcts in the spleen, kidneys, liver, and stomach

resulting in multiple acute organ failure and/or ischemic muscle

or digital necrosis.

-

- Based on morphology and location of a nematode within an

artery, Angiostrongylus sp. was also considered in the differential

diagnosis. The adults of Angiostrongylus vasorum reside in the

pulmonary arteries and right ventricle of dogs and foxes and

incite a proliferative endarteritis similar to that in dirofilariasis.

Angiostrongylus spp. are metastrongylid parasites characterized

by a large intestine with few multinucleate cells and a microvillar

border, in contrast to the small, indistinct intestine of Dirofilaria.

The presence of eggs in the uterus of adult angiostrongylidae

is another distinguishing morphologic feature.

-

- Conference participants also discussed several other intravascular

metazoan parasites known to occur in animals. Schistosoma sp.

(blood flukes) are trematodes that predominately affect portal

and mesenteric vessels in various animal species. The fourth

stage larvae of the nematode Strongylus vulgaris primarily affects

the mesenteric arteries of horses. Elaeophora schneideri, the

arterial worm of deer and sheep, is a nematode primarily affecting

the carotid arteries and is the cause of the clinical entity

known as sorehead.

-

- Contributor: Louisiana State University, School of

Veterinary Medicine, Baton Rouge, LA 70803.

-

- References:

- 1. Frank J, et al.: Systemic arterial dirofilariasis in five

dogs. J Vet Intern Med 11:189-194, 1997.

- 2. Goggin G, et al.: Ultrasonographic identification of Dirofilaria

immitis in the aorta and liver of a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc

210:1635-1637, 1997.

- 3. Henry CJ: Salivary mucocele associated with dirofilariasis

in a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 200:1965-1966, 1992.

- 4. Slonka FS, Castleman W, Krum S: Adult heartworms in the

arteries and veins of a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 170:717-719,

1977.

- 5. Chitwood M, Lichtenfels JR: Identification of parasitic

metazoa in tissue sections. In: Experimental Parasitology, 32:458-460

and 491-495, Academic Press, 1972.

- 6. Davidson WR, Nettles VF: White-tailed deer. In: Field

Manual of Wildlife Diseases in the Southeastern United States,

2nd ed., Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, University

of Georgia, GA, 1997.

-

- Case IV - 38613 (AFIP 2643569)

-

- Signalment: Nine-year-old, female, pygmy chimpanzee

(Pan paniscus).

-

- History: Several animals in the pygmy chimpanzee group

exhibited signs of upper respiratory tract infection including

nasal discharge, coughing, sneezing, tachypnea and open-mouth

breathing. The animals were also lethargic and inappetent. Animals

were treated symptomatically (expectorant, non-steroidal antiinflammatory

drug). This adult female was found dead on the morning of the

fourth day. She was three weeks post-parturient.

-

- Gross Pathology: Abundant mucopurulent to sanguineous

fluid flowed from the nostrils bilaterally. The nasal mucosa

was reddened. Bilaterally, vocal sacs contained abundant mucopurulent

to hemorrhagic exudate. A moderate amount of white froth partially

filled the trachea and bronchi. Dorsal-caudal lung lobes were

firm and discolored purple. Cranioventral lobes and the periphery

of the dorsal lobes were slightly firm and discolored. The cut

surfaces of the lungs were dry and dense. Sections of lung from

all areas were observed to float in formalin. Tracheobronchial

lymph nodes were mildly enlarged. The cervix was closed. The

uterus was mildly enlarged, had a slightly reddened mucosa, and

contained 3 to 5 milliliters of dark red/brown fluid, consistent

with post-partum status. Milk was easily expressed from both

teats.

-

- Laboratory Results:

-

- 1. Bacterial cultures:

a. Aerobic culture of lung: 1+ Streptococcus viridans group,

1+ Staphylococcus aureus.

b. Aerobic culture of vocal sac: 3+ Staphylococcus aureus.

c. Aerobic culture of heart blood: Streptococcus viridans group,

Enterobacter cloacae, non-hemolytic streptococcus, Staphylococcus

aureus, Streptococcus viridans group II, beta-hemolytic streptococci

group B.

d. Anaerobic culture of lung and vocal sac: No growth.

e. Fungal culture of lung and vocal sac: No growth.

f. Virus isolation lung and nasal exudate (Simian Diagnostic

Lab, San Antonio, TX): No virus isolated.

-

- 2. Cytology:

a. Nasal exudate: Mucopurulent exudate with numerous extra- and

intracellular gram-positive cocci.

b. Air sac: Purulent exudate, sloughed columnar epithelial cells

and extra- and intracellular gram-positive cocci.

c. Lung: Abundant neutrophils and erythrocytes, with fewer macrophages

and epithelial cells. Macrophages tend to have abundant foamy

cytoplasm. Epithelial cells have enlarged nuclei, and there are

occasional binucleated forms. Low numbers of intracellular gram-positive

cocci and occasional large extracellular gram-positive rods are

detected.

d. Uterus: Abundant erythrocytes with low to moderate numbers

of foamy macrophages. Small amounts of pigment (hemosiderin)

and degenerate neutrophils.

-

- 3. Immunofluorescence (direct or indirect IFA) of

nasal epithelial scraping (Rhinoprobe, University of San Diego

Medical Center):

a. Positive for respiratory syncytial virus.

b. Negative for parainfluenza 1, 2, 3; adenovirus; influenza

A and B.

- 4. Immunohistochemistry of lung (R. C. Hackman, Fred Hutchinson

Cancer Research Center): Positive for respiratory syncytial virus.

-

- Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments:

- 1. Lungs: Severe, diffuse, subacute, suppurative bronchoalveolar

pneumonia with type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia, hypertrophy and

syncytial cell formation.

2. Lung: Mild, multifocal, chronic acariasis (not present in

all sections).

- Etiology: Respiratory Syncytial Virus with secondary

bacterial infection (gram-positive cocci).

-

- Syncytial cell formation in alveolar epithelium with degeneration

and necrosis of bronchiolar and, to a lesser extent, bronchial

epithelium are characteristic of respiratory syncytial virus

(RSV) infection. Positive immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

confirmed the diagnosis of RSV infection. The marked suppurative

nature of the lesion in this case may be due to secondary bacterial

infection, though neutrophils may be a prominent component of

RSV pneumonia.

-

- RSV infection is a common cause of morbidity in human infants

and children. Mortality is uncommon and generally occurs in children

with underlying pulmonary, cardiac or immunosuppressive disease.

Disease in adult humans is usually limited to mild cold symptoms.

Adult fatality is rare unless complicated by immunosuppression

or general debilitation (old age). Although it is common knowledge

that chimpanzees and a few other primate species are susceptible

to RSV infection, there are very few reports or descriptions

of naturally acquired RSV pneumonia in the literature.

2x

obj

2x

obj

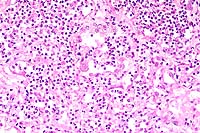

- Case 10-4. Lung. Bronchointerstitial pneumonia. A

suppurative exudate fills many alveoli.

20x

obj

20x

obj

- Case 10-4. Higher magnification demonstrates type

II pneumocyte hyperplasia, syncytial giant cells, and suppurative

alveolar exudate.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, broncho-interstitial,

acute to subacute, diffuse, severe, with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia,

edema, syncytial cells, and cocci, pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus),

nonhuman primate.

-

- Note: Some sections contain lung mites.

-

- Conference Note: Some conference participants identified

rare arthropod parasites within bronchioles. The morphology of

these lung mites is consistent with Pneumonyssus sp. Cocci are

gram-positive by the Brown and Brenn staining method.

-

- Respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV) are best known as causes

of respiratory disease in humans, other primates, and cattle

(bovine RSV). RSV is a single-stranded, encapsulated, RNA virus

that matures by budding through the cytoplasmic membrane. It

is classified as a pneumovirus (subfamily pneumovirinae) in the

family Paramyxoviridae. The genus pneumovirus also contains a

virus that causes pneumonia in mice, though it is antigenically

unrelated to RSV in humans or cattle. The other subfamily of

the Paramyxoviridae, paramyxovirinae, includes paramyxovirus

(parainfluenza 1, 2 , and 3, equine paramyxovirus, snake paramyxovirus),

morbillivirus (measles, canine distemper, rinderpest, phocine

distemper, cetacean morbillivirus), and rubulavirus (velogenic

viscerotropic Newcastle disease).

-

- In nonhuman primates, RSV was first isolated from a chimpanzee

with respiratory disease and called chimpanzee coryza agent (coryza

meaning inflammation with discharge from the nasal mucosa). Viral

pneumonias may predispose animals to secondary pulmonary bacterial

infection by compromising host defense mechanisms, and RSV infection

likely predisposed this animal to infection by the gram-positive

cocci.

-

- Other potential causes of viral respiratory disease in nonhuman

primates include adenovirus, herpesvirus, orthomyxovirus (influenza),

paramyxovirus (parainfluenza), picornavirus, and morbillivirus

(measles). Conference participants particularly considered measles

virus due to the similarity in microscopic findings to RSV. Both

viral pneumonias may cause type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, syncytial

cell formation, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic and intranuclear

inclusions. While RSV infection is almost always limited to the

respiratory tract, measles virus often manifests with a concurrent

maculopapular rash and erythema, especially on the face. Other

systemic features of measles virus infection include white, necrotic

foci on the gingiva and tongue, generalized lymphadenopathy,

and syncytial cells and inclusions in various organs including

the liver, lymph nodes, intestines, salivary glands, and lungs.

-

- Contributor: Department of Pathology, Zoological Society

of San Diego, P.O. Box 120551, San Diego, CA 92112-0551.

-

- References:

- 1. Clarke CJ, et al.: Respiratory syncytial virus-associated

bronchopneumonia in a young chimpanzee. J Comp Path 110:207-212,

1994.

- 2. Kalter SS, Heberling RL: Primate viral diseases in perspective.

J Med Primatol 19:519-535, 1990.

- 3. Miller RR: Viral infections of the respiratory tract.

In: Pathology of the Lung, Thurlbeck WM, Churg AM eds., Theime

Medical Publishers Inc., New York, 1995.

- 4. Sedgwick CJ, Robinson PT, Lochner FK: Zoonoses: A zoo's

concern. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 167:828-829, 1975.

- 5. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T: Infectious diseases. In:

Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 6th ed., pp. 340-341, WB

Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1999.

- 6. Miller, MJ: Viral taxonomy. In: Clinical Infectious Diseases

25:18-20, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, 1997.

- 7. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by viruses.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 310-322, Williams &

Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, 1997.

-

- Ed Stevens, DVM

Captain, United States Army

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: STEVENSE@afip.osd.mil

-

- * The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

- Return to WSC Case Menu

2x

obj

2x

obj

20x

obj

20x

obj

4x obj

4x obj

40x

obj, Giemsa

40x

obj, Giemsa

2x

obj

2x

obj 10x

obj

10x

obj

2x

obj

2x

obj

20x

obj

20x

obj