Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 5

30 September 1998

- Conference Moderator:

Dr. Terrance Wilson, Diplomate, ACVP

USDA Emergency Programs

Unit 41

4700 River Road

Riverdale, MD 20737-1231

NOTE: Click on images for larger views. Use

browser's "Back" button to return to this page.

Return to WSC Case Menu

Case I - 96/1255 (AFIP 2550628);

- one 2x2 histology color photo transparency

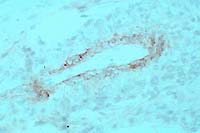

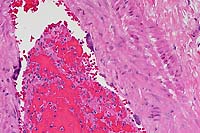

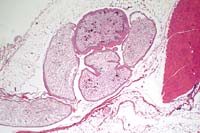

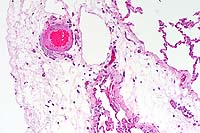

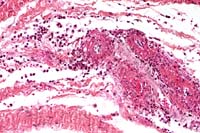

- Case 5-1. Immunohistochemical stain for BVD virus

structural & non-structural proteins

- Note positive staining of blood vessel tunica media.

-

- Signalment: A six-month-old, Brown Swiss calf was

presented to the clinic with signs of respiratory distress.

-

- History: Two calves from the same farm died a few

days previously. Upon admission, the calf was in poor body condition,

had a rectal temperature of 39.8°C, a heart rate of 60 beats

per minute, and a respiratory rate of 60 breaths per minute.

The animal coughed spontaneously. The clinicians detected loud

respiratory signs in the ventral lung fields. The muzzle was

dry, and the eyes were sunken. The calf was treated with NaCl-glucose,

Clamoxylä, Flumilarä, and Ventipulminä. The calf's

condition deteriorated over a five day period and was euthanized.

-

- Gross Pathology: The calf was thin. There were multiple

clumps of doughy, yellow, exudate in the tracheal lumen, and

the tracheal mucosa was reddened. The cranial lung lobes were

consolidated. On cut surface, a yellow-green, creamy mass was

seen in the bronchi and bronchioli. The ventral portions of all

left lung lobes were consolidated. All lung-associated lymph

nodes were enlarged and edematous. The heart and other organs

showed no macroscopic changes.

-

- Laboratory Results:

-

- Cytology Tracheobronchial wash:

- Macrophages: +

Neutrophils: +++

Bacteria: ++

Cell detritus: +++

-

- Bacteriology Tracheobronchial wash:

++/+++ Pasteurella haemolytica Biovar A

+ Leukocytes (microscopically)

-

- Radiography: A peribronchial interstitial pattern

could be seen in the dorsal areas of the lungs, and a bronchopneumonia

was detected in the ventral areas of the lungs.

-

- Parasitology: Eimeria, Trichostrongyles, and Strongylids

were detected.

-

- Hematology:

- 1. Hct: 20% (normal: 24-35%)

- 2. Hgb: 7.2 g/dl (normal: 8.3-11.7 g/dl)

- 3. Leukocytes: 2700/ml (normal: 4240-9090/ml)

- 4. Lymphocytes: 1782/ml (normal: 2192-5117/ml)

- 5. Fibrinogen: 16g/l (normal: 2-9 g/l)

-

- Histology: The following organs were histologically

examined: Lung; pulmonary lymph node; heart; liver; spleen; kidney;

intestine; and brain.

-

- Immunohistochemistry: Immunohistochemistry was performed

on snap-frozen sections of skin, thyroid gland, tongue and abomasum

collected at necropsy. Immunohistochemistry of the heart was

performed on paraffin-embedded tissue. Four monoclonal antibodies

against BVD-virus structural and non-structural proteins were

applied using the LSAB-method. All organs examined were positively

labeled. A positive control from a reference calf was run with

each batch of monoclonal antibodies. A negative control with

PBS (pH 8) was made with each slide.

- BVDV-LSAB

|

Organs |

Monoclonal Antibodies |

|

Ca3/34-C42 |

C16 |

C42 |

15c5 |

|

Skin |

+ |

++ |

+ |

++ |

|

Thyroid |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Tongue |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Abomasum |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Heart |

+ |

nd |

++ |

++ |

(nd= not done)

-

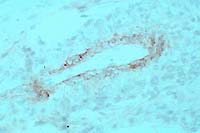

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Heart: Moderate

subacute perivasculitis and vasculitis. Mild multifocal subacute

myocarditis. Lung: Severe chronic bronchointerstitial pneumonia

with bronchiectasia and bronchiolitis obliterans (not submitted).

-

- The heart is submitted for Wednesday Slide Conference. The

perivascular region and the vessel walls are infiltrated with

mononuclear inflammatory cells. The endothelial cells are activated,

and in some regions there is a hyaline degeneration of the vessel

wall. This vasculitis was seen in the brain, intestine (vessels

of the submucosa), and the heart.

-

- The vasculitis is linked to a BVD-virus infection. It is

known that infection with this pestivirus can induce perivasculitis

and vasculitis with mononuclear inflammatory cells. These lesions

can be found in the intestine, the brain, the heart, the adrenal

cortices and other organs. Sometimes hyaline degeneration and

fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls in the submucosa of the

intestine and other organs can also be seen. Therefore, it is

difficult to differentiate vasculitis due to BVD-virus from that

seen in malignant catarrhal fever.

-

- BVD-virus can induce immunotolerance, persistent infection,

or mucosal disease. The course of the disease depends on the

time of infection (prenatal or postnatal) and the viral strains

involved. Due to BVD virus-induced immunosuppression, the calf

became susceptible to respiratory infection.

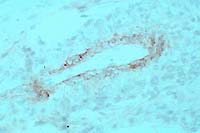

- Case 5-1. Immunohistochemical stain for BVD virus

structural & non-structural proteins

- Note positive staining of blood vessel tunica media.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

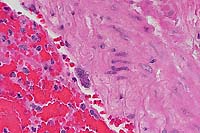

- Case 5-1. Heart: Note moderate influx of lymphocytes,

few histiocytes, and rare neutrophils within and around the vessel

wall.

AFIP Diagnosis: Heart, myocardium: Vasculitis and perivasculitis,

lymphohistiocytic and plasmacytic, multifocal, moderate, with

vascular fibrinoid necrosis, mild interstitial edema, and myocardial

necrosis, Brown Swiss, bovine.

-

- Conference Note: Sarcocysts are infrequently present

in some sections. Multifocal myocardial degeneration is also

present in some of the examined sections.

-

- Most conference participants agreed that fibrinoid necrosis

of vessels with perivascular distribution of inflammatory cells

in the myocardium is an unusual feature of BVD-virus (BVDV) infection.

Vasculitis has been frequently reported in arterioles of the

mesentery and intestinal submucosa. It has also been reported

in other organs, including the heart. A differential diagnosis

for bovine viral myocarditis discussed by conference participants

included malignant catarrhal fever (MCF) and rinderpest.

-

- Bovine viral diarrhea virus is a pestivirus which occurs

as cytopathogenic (cp) and noncytopathogenic (noncp) biotypes

based on their effects on tissue culture cells. The cytopathogenic

virus causes diarrhea in cattle exposed postnatally between six

months and two years of age. Clinically, the virus usually causes

a mild, acute, transient diarrhea with high morbidity. In some

cases, new strains of cpBVDV have caused outbreaks with high

mortality rates.

-

- Mucosal disease occurs in cattle that become infected in

utero with noncpBVDV. These animals develop a persistent infection

with the subsequent development of immunotolerance. Mucosal disease,

which is almost invariably fatal, generally develops in animals

between six months and two years of age and occurs when the noncpBVDV

is transformed to cpBVDV through RNA recombination. Superinfection

of cpBVDV may cause mucosal disease in persistently infected

animals if the cytopathogenic strain antigenically matches the

noncytopathogenic strain. Antigenically different cpBVDV strains

will not cause mucosal disease.

-

- Pestiviruses are enveloped, RNA viruses that measure 40 to

70nm in diameter. The pestivirus genus in the family Flaviviridae

also includes the viruses which cause hog cholera in swine and

border disease in sheep. Swine may be infected with BVDV, but

the virus does not cause clinical disease with the exception

of pregnant sows in which fetal death and resorption may occur.

-

- While the character and distribution of histologic lesions

may suggest a specific etiology, ancillary diagnostic tests and

procedures are often required to accurately diagnosis the various

bovine viral gastrointestinal and vesicular diseases. Virus isolation

requires labor intensive methods, prolonged periods of time,

and may fail to detect infection in a significant number of animals.

Recently developed immunohistochemical methods and polymerase

chain reaction tests provide practical, rapid means to accurately

confirm BVDV infection in animals.

-

- Rinderpest, a morbillivirus of the family Paramyxoviridae,

causes necrosis of intestinal glands and Peyer's patches reminiscent

of the gastrointestinal lesions of BVD. Rinderpest may also cause

a necrotizing vasculitis; however, syncytial cells with eosinophilic

intracytoplasmic inclusions are often seen histologically in

cattle infected with rinderpest, and when present, distinguish

it from BVD and MCF. Intranuclear inclusions may also occur within

the syncytial cells of rinderpest lesions.

-

- MCF, caused by a lymphotrophic gammaherpesvirus, causes a

marked perivascular and intramural infiltration of predominately

large lymphocytes with large nuclei and prominent nucleoli. There

is often an associated fibrinoid necrotizing vasculitis. The

characteristic inflammatory infiltrates and vascular changes

occur in almost all organs. Unlike rinderpest and BVD, the underlying

lymphoproliferative nature of MCF often causes a prominent lymphocytic

hyperplasia in multiple lymph nodes and prominent lymphoid follicles

in the splenic white pulp. The vascular lesions are more consistently

present and more severe in MCF than in BVD.

-

- Contributor: Institute of Veterinary Pathology, University

of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. 268, Zurich Switzerland 8057.

-

- References:

- 1. Kent TH, Moon HW: The comparative pathogenesis of some

enteric diseases. Vet Path 10:414-469, 1973.

- 2. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N: The alimentary system.

In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., vol. 2, pp. 149-158,

Academic Press Inc., 1993.

- 3. Baszler TV, Evermann J, Kaylor PS, Byington TC, Dilbeck

PM: Diagnosis of naturally occurring bovine viral diarrhea virus

infection in ruminants using monoclonal antibody-based immunohistochemistry.

Vet Pathol 32: 609-628, 1995.

- 4. Thur B, Zlinsky K, Ehrensperger F: Immunohistochemical

detection of bovine viral diarrhea virus in skin biopsies: A

reliable and fast diagnostic tool. J Vet Med B43:163-166, 1996.

5. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by viruses. In:

Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed. Williams and Wilkins. pp. 299-302,

1997.

-

Case II - 96/558/4 (AFIP 2641092)

- Signalment: An adult horse.

-

- History: A horse was inoculated orally with 50,000

TCID50 equine morbillivirus/Hendra virus (EMV/HeV). Seven days

post inoculation, it developed tachycardia, anorexia, lethargy,

and increased respiratory rate. The horse deteriorated over the

next 24 hours and was euthanized.

-

- Gross Pathology: At necropsy there was marked pulmonary

edema with marked dilatation of lymphatics over the pleural surface

of the lung. All lymph nodes were congested. There were no other

gross post mortem lesions.

-

- Laboratory Results: Virus was isolated from the lung,

kidney, spleen, and urine. Lung, kidney, and many other tissues

were positive by indirect immunoperoxidase test using a rabbit

polyclonal serum to inactivated EMV/HeV.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

- 1. Lungs: Edema, subacute (severe interlobular) and vasculopathy

with endothelial syncytia.

- 2. Kidneys: Vasculopathy with endothelial syncytia.

-

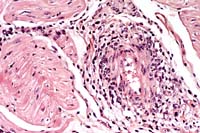

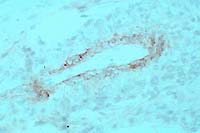

- The presence of syncytial endothelial cells in small and

medium-sized vessels in many organs is a diagnostic feature of

this disease, and in some lung sections in this case, is associated

with mural necrosis and lymphoid cell infiltration. Laboratory

methods demonstrated that viral antigen was confined to vascular

tissue and was readily identified in the tunica intima of arteries

and veins. The tunica media had positive immunostaining in a

smaller number of blood vessels. Positive immunostaining has

been observed in syncytial endothelial cells which are characteristic

of this infection.

In September 1994 in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane, Australia,

infection with a previously undescribed member of the Paramyxoviridae

family resulted in the deaths of 13 horses and one human (the

adult male horse trainer) from an acute respiratory disease.

The virus was provisionally designated as equine morbillivirus,

but subsequent studies [3,4]; indicated the virus cannot be easily

classified in any of the existing genera in the family Paramyxoviridae.

Consequently, the virus has been renamed Hendra virus (HeV) [3,4,5].

-

- In October 1995, a farmer developed fatal encephalitis as

a result of HeV infection which was attributed to exposure to

two HeV infected horses that had died more than one year earlier

[7]. Extensive serological surveys throughout Queensland have

found no further evidence of HeV infection in horses or humans

[8,9]. However, fruit bats (flying foxes, Pteropus sp.) were

found to have a high prevalence of serological reactors to HeV

indicating they may be a wildlife reservoir of the virus [10].

Serological evidence of HeV infection has not been found in any

animal species other than fruit bats. In experimental studies,

guinea pigs and cats have been found to be susceptible to HeV

infection [11,12]. The lesions of HeV infection in horses have

been described by Hooper et al [13].

10x

obj

10x

obj

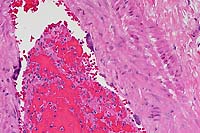

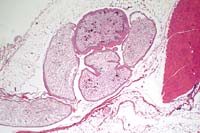

- Case 5- 2. Lung. The pleura and interlobular

septa are markedly expanded by clear space (edema) and scattered

lymphocytes an plasma cells. A pleural arteriole has fibrinoid

degeneration and necrosis of its walls with infiltrating and

adjacent lymphocytes and plasma cells.

20x

obj.

20x

obj. 40x

obj

40x

obj

- Case 5- 2. Lung. Attached to the wall of this

pulmonary artery there are 3 endothelial syncytial cells. A 40x

objective view illustrates an eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion

body separating the several of the nuclei of this cell.

20x

obj

20x

obj

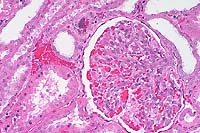

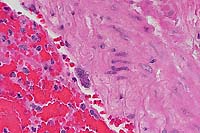

- Case 5- 2. Kidney. Note the syncytial endothelial

cell expanding the wall of a small arteriole adjacent to the

glomerulus.

AFIP Diagnosis:

- 1. Lung: Vasculopathy, characterized by endothelial syncytia,

mural necrosis, fibrinoid change, subacute perivasculitis, and

moderate interstitial edema, breed unspecified, equine.

- 2. Kidney, interstitial and glomerular blood vessels: Vasculopathy,

characterized by endothelial syncytia, mural necrosis, and fibrinoid

change.

-

- Conference Note: In some sections of lung and kidney,

rare eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions are present within

endothelial syncytia. Mild degenerative changes of glomeruli

and tubular dilatation were also noted by some conference participants.

-

- The two recent outbreaks of a previously unrecognized equine

and human viral disease in Australia have sparked an intense

research effort to determine the pathogenesis, species susceptibility,

and reservoir of the virus. The disease in naturally infected

horses is characterized by an acute onset of respiratory distress,

anorexia, fever, depression, ataxia, and high mortality. As indicated

by the contributor, this is a zoonotic disease. The virus has

caused illness in three humans with two fatalities. Because of

the uncertain classification of this newly recognized virus,

it will be referred to in this text as equine morbillivirus/Hendra

virus (EMV/HeV).

-

- Experimentally, EMV/HeV causes lethal disease in horses,

cats, and guinea pigs, while dogs, mice, rats, chickens and rabbits

are refractory to infection. The lesion leading to death in experimentally

infected horses and cats is interstitial pneumonia with pulmonary

edema and accumulation of alveolar macrophages which develops

subsequent to virus-induced vascular changes. Intramural edema,

fibrinoid necrosis, endothelial syncytia, and perivascular mononuclear

cell inflammatory infiltrates characterize the vascular changes.

In horses, parenchymal lesions secondary to the vascular changes

more commonly occur in the kidney and brain, while in cats, histologic

changes in the gastrointestinal tract are more frequently observed.

(The authors of the initial experimental investigation of EMV/HeV

speculate that the variations in the distribution of lesions

may be due to limited sampling of the equine gut. The urgency

to establish the cause of the disease preempted an in-depth systematic

study of the virus in horses).

-

- The most significant gross lesion observed in experimentally

infected horses is pulmonary edema with subpleural lymphangiectasis.

The abundant frothy discharge present in the upper respiratory

tract in naturally infected horses did not occur in experimentally

infected horses; this may be due to environmental factors, various

treatments applied to field cases, and increased time of lesion

development in natural infections. In experimentally infected

cats, hydrothorax and pulmonary edema are the prominent gross

lesions with varying amounts of congestion and pulmonary hemorrhage.

-

- In guinea pigs the fundamental histopathologic finding is

fibrinoid degeneration/necrosis of small blood vessels surrounded

by a mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate, similar to horses

and cats. Additionally, the presence of endothelial syncytia

is common to all three of the susceptible species. Unlike horses

and cats, however, immunohistochemistry demonstrates that the

virus preferentially affects the larger vessels in guinea pigs

rather than the smaller vessels. This finding may explain the

lack of severe pulmonary edema in infected guinea pigs, the fatal

lesion of cats and horses. EMV/HeV does cause widespread vascular

disease in guinea pigs and is responsible for lesions in a variety

of organs. Cyanosis is observed grossly in infected guinea pigs

and is thought to be caused by myocardial insufficiency, failure

of the intercostal musculature, and/or failure of the lungs,

rather than pulmonary edema.

-

- Morbilliviruses are relatively large (150-250 nm), enveloped,

and contain single-stranded RNA. Examples of other morbilliviral

diseases include canine distemper, peste des petits ruminants,

phocine distemper, dolphin morbilliviral disease, and measles.

While interstitial pneumonia with syncytial cells is commonly

seen in morbilliviral infections, EMV/HeV is unique in that it

demonstrates a greater affinity for vascular tissues than the

other morbilliviruses. The other morbilliviruses, such as measles

and canine distemper, may infect endothelium but do not cause

the vascular lesions observed in EMV/HeV. This vascular tropism

occurs in both intravenously inoculated horses and subcutaneously

inoculated cats and guinea pigs, suggesting that this affinity

for blood vessels is real rather than a function of the route

of inoculation.

-

- Histologically, the vascular degeneration of EMV/HeV infection

resembles the changes observed in equine viral arteritis. Grossly,

African horse sickness causes pulmonary edema very similar to

that of EMV/HeV and should be considered in the differential

diagnosis.

-

- While investigators of the experimental equine cases noted

a histological absence of intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions

within syncytia, a few conference participants identified rare

eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions within endothelial syncytia,

especially within the renal vasculature. This histologic finding

is consistent with other morbilliviral infections.

-

- Contributor: Australian Animal Health Laboratory,

Ryrie Street, Geelong, Victoria, Australia 3219.

-

- References:

- 1. Murray PK, Selleck PW, Hooper PT et al.: A morbillivirus

that caused fatal disease in horses and humans. Science 268:94-96,

1995.

- 2. Selvey LA, Wells RM, McCormack JG et al.: Infections of

humans and horses by a newly described morbillivirus. Med J Aust

162:642-645, 1995.

- 3. Wang LF, Michalski W, Yy M, Pritchard LI, Crameri G, Shiell

B, Eaton BT: Novel P/V/C gene in a new Paramyxoviridae virus

which causes lethal infection in humans, horses and other animals.

J Virol 72:1482-1490, 1998.

- 4. Yu M, Hannsson E, Shiell B, Michalski W, Eaton BT, Wang

LF: Sequence analysis of the Hendra virus nucleoprotein gene:

Comparison with other members of the subfamily Paramyxovirinae.

J Gen Virol (in press).

- 5. Murray PK, Eaton B, Hooper P, et al.: Flying foxes, horses

and humans: A zoonosis caused by a new member of the Paramyxoviridae.

In: Emerging Infections 1, pp. 43-58, ASM Press, Washington D.C.,

1998.

- 6. O'Sullivan JD, Allworth AM, Paterson DL et al.: Fatal

encephalitis due to novel paramyxovirus transmitted from horses.

Lancet 349:93-95, 1997.

- 7. Hooper PT, Gould AR, Russell GM, Kattenbelt JA, Mitchell

G: The retrospective diagnosis of a second outbreak of equine

morbillivirus infection. Aust Vet J 74: 244-245, 1996.

- 8. Selvey L, Taylor R, Arklay A, Gerrard J: Screening of

bat carriers for antibodies to equine morbillivirus. Comm Dis

Intell 20:477-478, 1996.

- 9. Ward MP, Black PF, Childs AJ, et al.: Negative findings

from serological studies of equine morbillivirus in the Queensland

horse population. Aust Vet J 74:241-243, 1996.

- 10. Young PL, Halpin K, Selleck P et al.: Serological evidence

for the presence in pteropus bats of a paramyxovirus related

to equine morbillivirus. Emerg Infect Dis 2:239-240, 1996.

- 11. Westbury HA, Hooper PT, Selleck PW, Murray PK: Equine

morbillivirus pneumonia: Susceptibility of laboratory animals

to the virus. Aust Vet J 72:278-279, 1995.

- 12. Hooper PT, Ketterer PJ, Hyatt AD, Russell GM: Lesions

of experimental equine morbillivirus pneumonia in horses. Vet

Pathol 34:312-322, 1997.

- 13. Hooper PT, Westbury HA, Russell GM: The lesions of experimental

equine morbillivirus disease in cats and guinea pigs. Vet Pathol

34323-329, 1997.

-

Case III - 96-9621 (AFIP 2639838)

- Signalment: A seven-week-old, crossbred pig.

-

- History: This pig, from a multisource nursery facility

of about 700 animals, spontaneously developed an unusual dermatitis.

Two other pigs in this group developed similar lesions.

-

- Gross Pathology: Round to irregular, red to purple

macules and papules, often coalescing to form large irregular

patches and plaques, were present on the perineal area of the

hindquarters, limbs, ears, and ventral abdomen. There was subcutaneous

edema of the dependent sites.

-

- Laboratory Results: Bacterial cultures were negative.

Porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus (PRRSV) was

detected in tissue homogenate samples by PCR and virus isolation.

Fluorescent antibody test was positive for porcine IgM and C3

within dermal blood vessels.

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Cutaneous vasculitis,

necrotizing and neutrophilic, with leucocytoclasia, thrombosis,

dermal hemorrhages and focal coagulative epidermal necrosis.

-

- Haired skin from the perineal area and from an ear are submitted.

A severe necrotizing vasculitis affecting small-caliber vessels

is characterized by infiltration of the vascular wall by neutrophils,

leucocytoclasia, fibrin exudation, and thromboses with reactive-hypertrophied

endothelial cells. In some sections these changes are best observed

in the deeper dermis and panniculus. Other cutaneous changes

include severe dermal hemorrhages, perivascular infiltration

of mononuclear cells and eosinophils, and coagulative necrosis

of the epidermis. Lesions found in other organs included bronchointerstitial

pneumonia, generalized reactive lymphadenopathy, and perivascular

cuffing of mononuclear cells in various tissues including skin.

-

- The cutaneous lesions in this case are part of a porcine

systemic vascular disease first recognized in the United Kingdom

[1,2], and subsequently in several countries including Canada

[3,4] and the United States [5]. Because of the frequent involvement

of the skin and kidneys among organs affected with the vascular

lesions, the disease was originally called porcine dermatitis/nephropathy

syndrome [1]. The disease affects mainly grower pigs and has

a low prevalence in swine herds. The prognosis of the condition

in affected pigs is dependent on the extent and the severity

of the vascular lesions found in internal organs, particularly

within the kidneys in which a severe exudative and necrotizing

glomerulonephritis may develop. The gross appearance and the

distribution of the cutaneous lesions in this animal are characteristic

of the disease in its acute stage.

-

- This vascular disease mainly involves small-caliber blood

vessels and appears to be immune-mediated [4,6]. The cause of

the condition is still undetermined, but it has been suggested

that PRRSV infection may play a role in the pathogenesis of this

systemic vascular disease of swine [4,7].

-

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

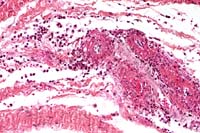

- Case 5-3. Dermis. There is a brisk infiltrate

of neutrophils and eosinophils around, infiltrating, and effacing

the necrotic walls of two parallel arterioles.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin: Vasculitis and perivasculitis,

necrotizing, neutrophilic and eosinophilic, acute, with multifocally

extensive dermal and subcutaneous hemorrhage, multifocal epidermal

necrosis, and mild epidermal hyperplasia, cross-bred pig, porcine.

-

- Conference Note: Porcine reproductive and respiratory

syndrome (PRRS) is a disease of pigs caused by an arterivirus

that commonly manifests as reproductive failure in sows, pneumonia

in young swine, and increased preweaning mortality. Additionally,

immunohistochemical studies suggest an association between PRRS

virus and a recently recognized systemic vasculitis primarily

affecting the skin and kidneys in young growing pigs, initially

termed dermatitis/nephropathy syndrome. In pigs with skin and

kidney lesions typical of the disease, viral antigen has been

detected in macrophages surrounding affected vessels. Through

the use of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, PRRS

viral RNA has been detected in the lung and spleen of these animals.

-

- In addition to the gross lesions in the skin, the kidneys

may occasionally be swollen, pale, and contain numerous cortical

petechial hemorrhages, the result of an underlying necrotizing

vasculitis which occurs in the small and medium-sized vessels.

Pneumonia with generalized lymphadenopathy is usually observed

as well. The distribution of the cutaneous lesions described

by the contributor is typical for this entity. The acute cutaneous

lesions are hemorrhages due to necrotizing vasculitis, while

chronic lesions are brown crusts that cover ulcerated or excoriated

areas of skin.

-

- This systemic vascular disease of swine shares several similarities

with some of the human cutaneous vasculitides; leukocytoclastic

vasculitis in people occurs as hemorrhagic coalescing papules

and plaques often on dependent sites of the body such as the

legs and arms. Cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis often accompanies

systemic disease. While the skin may be the only organ affected,

other internal organs including the kidneys, central nervous

system, gastrointestinal tract, and joints, are often involved.

This is true in both pigs and humans. Systemic vasculitis may

occur from direct injury to vessels by infectious agents or by

immune-mediated mechanisms; most cutaneous vasculitides are thought

to be immune-mediated. Immune-mediated vascular damage may occur

through one of several mechanisms including formation or deposition

of immune complexes in vessels followed by cell-mediated or cytotoxic

antibody attack of vessels.

Several etiologies should be considered for erythema or skin

discoloration in pigs. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, or swine

erysipelas, causes characteristic rhomboid or "diamond skin"

lesions acutely in pigs; the causative agent is a small, pleomorphic,

gram-positive bacterial rod that is sensitive to penicillin.

Bacterial septicemia caused by a variety of agents (Streptococcus

suis, Actinobacillus suis, A. pleuropneumoniae) may cause transitory

reddish discoloration of the skin. Additionally, salmonellosis,

Hemophilus parasuis, A. suis, and swine erysipelas may cause

cyanosis and congestion of the extremities with petechiation

and congestion in several organs. Porcine stress syndrome, associated

with handling or similar stresses in genetically predisposed

animals, may cause generalized blotchy blue or red discoloration

of the skin; usually there is also associated skeletal or myocardial

necrosis.

-

- Contributor: Department of Pathology and Microbiology,

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Montreal, C.P.

5000 St-Hyacinthe, P.Q. Canada J2S 7C6.

-

- References:

- 1. Smith WJ, Thomson JR, Done S: Dermatitis/nephropathy syndrome

of pigs. Vet Rec 132:47, 1993.

- 2. White M, Higgins RJ: Dermatitis/nephropathy syndrome of

pigs. Vet Rec 132:199, 1993.

- 3. Hélie P, Drolet R, Germain M-C, Bourgault A: Systemic

necrotizing vasculitis and glomerulonephritis in grower pigs

in southwestern Quebec. Can Vet J 36:50-154, 1995.

- 4. Thibault S, Drolet R, Germain M-C, D'Allaire S, et al.:

Cutaneous and systemic necrotizing vasculitis in swine. Vet Pathol

35:108-116, 1998.

- 5. Duran CO, Ramos-Varas JA, Render JA: Porcine dermatitis

and nephropathy syndrome : A new condition to include in the

differential diagnosis list for skin discoloration in swine.

Swine Health Prod 5:241-245, 1997.

- 6. Sierra MA, de las Mulas JM, Molenbeek RF, van Maanen C

et al.: Porcine immune complex glomerulonephritis dermatitis

(PIGD) syndrome. Europ J Vet Pathol 3:63-70, 1997.

- 7. Segales J, Piella J, Marco E, Mateu-de-Antonio EM, et

al.: Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome in Spain. Vet

Rec 142:483-486, 1998.

-

Case IV - A44522 (AFIP 2638306)

- Case 5-4. Gross. Overlying the muscle fascia there

are two yellowish-tan serpentine parasites with a bulbous end

and a slender body.

-

- Signalment: Tissues from adult feral hogs, Sus scrofa.

-

- History: The submitted tissues are from Florida feral

hogs that were trapped by local hunters in the Lake Okeechobee

and Placid area. After being transported to a Texas slaughter

establishment, they were slaughtered under United States Department

of Agriculture (USDA) inspection for human consumption. In April,

1998, while performing routine postmortem inspection of these

animals, the USDA veterinarian identified 1-3 cm, white to tan-yellow

lesions on the surfaces of the thoracic, thigh, and triceps musculature.

Some of the lesions and associated muscle were collected and

fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histologic examination.

-

- Gross Pathology: Distributed on the surfaces of muscles

(abdominal, shoulder, thigh), and sometimes within the musculature

itself, were 1-3 cm, white to tan-yellow nodules. The nodules

were composed of a thin outer layer of connective tissue and

fat. Upon incision, the nodules contained a coiled, flat, slender,

white parasite, approximately 1 mm wide and up to 25 cm long.

The anterior end had a bulbous enlargement (2X3 mm) with a central

dimple or groove on the anterior aspect.

-

- Laboratory Results: None.

-

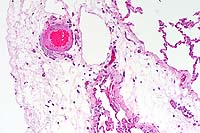

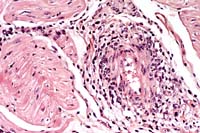

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Mild, multifocal

lymphoplasmacytic eosinophilic fasciitis with intralesional cestode

larvae, consistent with a pseudophyllidean plerocercoid.

-

- Histologically, there is a cystic space in the epimysial

connective tissue and fat. The space is surrounded by mild multifocal

infiltrates of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages.

The space contains single to multiple, closely bundled longitudinal

sections of a parasite. The parasite has irregular folds of pseudosegmentation

that is formed by a thick eosinophilic integument with inconspicuous

microvilli. There is an intervening layer of subintegumentary

cells that blend into a loose mesenchymal stroma that contains

calcareous corpuscles, longitudinal strips of smooth muscle,

and thin-walled excretory ducts.

-

- Sparganosis is an infection of tissues by the plerocercoid

stage of certain pseudophyllidean tapeworms. The plerocercoid

was originally called Sparganum, before the relationship to the

adult parasite was known. Adult stages of the parasite are typically

found in the intestine of domestic, feral, or wild canids and

felids, and eggs, rather than segments, are usually passed in

the feces. Water is required for maturation and development of

the ciliated coracidia from the egg, which is then followed by

ingestion of the coracidium by a copepod crustacean where it

develops into a procercoid. Due to this close relationship to

a water environment, common hosts for the final intermediate

plerocercoid stage include snakes and frogs. However, spargana

may develop in the tissues of essentially all vertebrates with

the exception of fish, by either ingestion of the procercoid

or plerocercoid stage.

-

- The importance of this infection lies in the serial transmission

of the plerocercoid in paratenic hosts, which may include food

animals and man. Spargana do not have distinct morphologic features,

and therefore they must be fed to a definitive host before taxonomic

separation into Spirometra and Diphyllobothrium species may be

attempted. Sparganosis, caused by Spirometra erinacei, is a well-defined

entity among local populations of feral hogs in Australia, where

expanded inspection procedures have been adopted when the parasite

is detected among animals slaughtered for human consumption.

The parasites are typically found in the connective tissues under

the peritoneum of the abdominal cavity, under the flare fat,

between abdominal muscles, under the skin of the inner aspect

of the hind legs, between the muscles of the hind legs, and under

the peritoneal lining of the abdominal organs and mesentery.

In contrast, report of infection of feral pigs in the United

States is rare.

-

- Grossly, the parasite may be mistaken for a small nerve or

blood vessel, and it may be easily overlooked unless the individual

is familiar with the disease and morphology of the parasite.

Consumption of undercooked or raw meat and the use of fresh tissues

as a poultice from an infected intermediate host have resulted

in human infections.

-

2x

obj.

2x

obj.

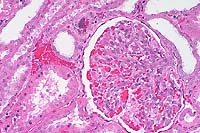

- Case 5-4. Muscle. Within the loose fibroadipose tissue

adjacent to skeletal muscle, there are multiple profiles of an

immature tapeworm (pleurocercoid), composed of loose mesenchyme

bearing abundant oval shaped calcified bodies (calcarious corpuscles).

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Skeletal muscle and fibroadipose tissue:

Plerocercoid (sparganum), with multifocal chronic-active and

eosinophilic myositis and steatitis, feral hog (Sus scrofa),

porcine.

-

- Conference Note: As noted by the contributor, sparganosis

may be acquired by humans through the ingestion of undercooked

pork, in which the plerocercoid larvae remain alive, and through

the application of infected fresh animal tissue poultices, as

is practiced in some cultures. Frogs are most commonly used in

this practice. The sparganum invades the human tissue where the

poultice is applied, most often the eye. Additionally, humans

may contract the disease through drinking water contaminated

with infected copepods.

-

- A rare form of human sparganosis has been described in which

the infective plerocercoids proliferate and invade every tissue

except bone. Only nine human cases of this proliferating sparganosis

have been reported in which extensive invasion of the larvae

into lymphatics produces pronounced edema and an elephantiasis-like

syndrome. No confirmed animal cases of this atypical form of

infection have been reported. The underlying cause of this variant

of sparganosis is unknown but is believed to be aberrant forms

of spirometrids. In general, sparganosis is a relatively benign

human and animal disease; it may be more prevalent than reported

due to this benign nature.

-

- Contributor: United States Department of Agriculture,

Food Safety and Inspection Service, Office of Public Health and

Safety, P.O. Box 6085, Athens, GA 30604.

-

- References:

- 1. Daly JJ: Sparganosis. In: CRC Handbook Series on Zoonoses.

Section C, Vol. 1, pp. 293-312, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1982.

- 2. Dunn AM: Veterinary Helminthology, 2nd ed., pp. 129-291,

YearBook Medical Publishers, Inc., Chicago, IL, 1978.

- 3. Mueller JF: The biology of Spirometra. J Parasitol 60:3-13,

1974.

- 4. Appleton PL, Norton JH: Sparganosis: A parasitic problem

in feral pigs. Queensland Ag J 102:339-343, 1976.

- 5. Smith HM, Davidson WR, Nettles VF, Gerrish RR: Parasitisms

among wild swine in southeastern United States. J Am Vet Med

Assoc 181:1281-1284, 1982.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #3629

-

- Ed Stevens, DVM

Captain, United States Army

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: STEVENSE@afip.osd.mil

-

- * The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

Return to WSC Case Menu

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

10x

obj

10x

obj

20x

obj.

20x

obj. 40x

obj

40x

obj

20x

obj

20x

obj

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

2x

obj.

2x

obj.