Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 4

23 September 1998

- Conference Moderator:

MAJ Dana P. Scott, Diplomate, ACVP

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

Washington, DC 20307

-

- NOTE: Click on images for larger views. Use

browser's "Back" button to return to this page.

Return to WSC Case Menu

-

- Case I - 351-97 (AFIP 2639852)

-

- Signalment: Juvenile striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis),

female, 3 and 1/2 months old.

-

- History: Part of a group of juvenile striped skunks

that were hand raised from birth by private individuals. These

skunks (N=10) were kept in quarantine for 24 days before this

skunk (351-97) died. No clinical signs were observed the day

before this animal's death. Blood was drawn for CBC and biochemistry

the day prior to death.

-

- Gross Pathology: Gross lesions included diffuse, mild

icterus in the subcutis and omental adipose tissue, and petechiae

and ecchymoses throughout the subcutis. There was approximately

1 ml of clear yellow fluid in the abdominal cavity. The liver

was markedly enlarged and diffusely mottled yellow, with an enlarged

and edematous gall bladder. Other gross findings included mild

bilateral renal enlargement and marked splenomegaly.

-

- Laboratory Results: Blood work revealed a low WBC

count (1595). The differential count was segmented neutrophils

(32%), lymphocytes (64%), and eosinophils (4%). Biochemistry

results demonstrated a very high AST (470 IU/L), ALT (332 IU/L),

total bilirubin (1.2 mg/dl), and LDH (1722 IU/L). There was slightly

decreased total protein (4.7 gm/dl) and hypoalbuminemia (2.0

gm/dl).

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

- 1. Liver: Hepatitis, subacute, diffuse, severe, with intranuclear

inclusion bodies and multifocal, minimal random necrosis and

hemorrhage, consistent with infectious canine hepatitis (canine

adenovirus Type 1).

- 2. Spleen: Congestion, diffuse, severe with intraphagocytic

hemosiderosis and few intraendothelial intranuclear amphophilic

to basophilic inclusion bodies, compatible with canine adenovirus

Type 1.

-

- Viral isolation, histologic features, and electron microscopy

confirm a diagnosis of infectious canine hepatitis (ICH) in this

striped skunk. Infectious canine hepatitis (canine adenovirus

type I) causes disease worldwide in many canidae, including domestic

dogs, foxes, skunks, wolves, and coyote (Cabasso 1981, Appel

1987). Karstad et al. (1975) document infectious canine hepatitis

causing acute, fatal hepatitis in striped skunks, and suggest

that striped skunks may be a natural wildlife host of infectious

canine hepatitis.

-

- Infectious canine hepatitis is spread by direct contact,

and the host becomes infected by ingestion of viral particles

in urine, feces, or saliva of infected animals. Infected urine

is the most important source for transmission, and the virus

may be shed in the urine for at least 6 months after infection

(Appel 1987). Infected animals may die acutely without clinical

signs or may have abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, petechial

and ecchymotic hemorrhages, and icterus (Appel 1987).

-

- Skunks and foxes with ICH often die acutely with no clinical

signs (Cabasso 1981). Canine adenovirus type I has an affinity

for hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and Kupffer cells, accounting

for the hemorrhage (due to vascular endothelial damage) and icterus

(hepatocyte damage) present grossly in many cases (Jones and

Hunt 1997).

-

- Animals that recover from infection or that have been vaccinated

with a live attenuated adenovirus vaccine may have a transient

immune complex uveitis, iridocyclitis, and corneal edema ("blue

eye") (Tizard 1996). Dogs that recover from infection are

immune to ICH for life (Appel 1987).

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

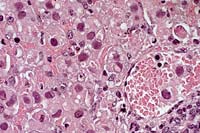

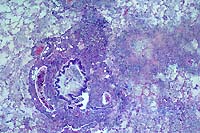

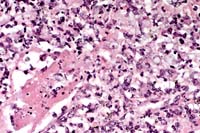

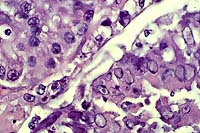

- Case 4-1. Liver. Large portal vein to right contains

sloughing cells with basophilic intranuclear inclusions. Similar

intranuclear inclusions are in most degenerating hepatocytes

as well.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatocellular degeneration

and necrosis, diffuse, with mild multifocal acute hepatitis and

vasculitis, numerous hepatocellular intranuclear inclusion bodies,

and rare endothelial intranuclear inclusion bodies, striped skunk

(Mephitis mephitis), mustelid.

-

- Conference Note: Canine adenovirus type-1 (CAV-1)

has worldwide serologic homogeneity and shares many immunologic

similarities to human adenoviruses, but is antigenically and

genetically distinct from CAV-2, a cause of respiratory disease

in the dog. In immunohistochemical studies performed at the AFIP,

positive staining of intranuclear inclusion bodies was observed

in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and endothelial cells utilizing

antibodies to human adenovirus.

-

- After gaining entry through the oronasal cavity, the virus

localizes in the tonsils and then spreads to other lymphoid organs.

In rare instances, severe tonsillitis is associated with edema

of the larynx or pharynx that can be fatal. The virus reaches

the blood via the thoracic duct and viremia ensues, lasting four

to eight days post infection. The virus becomes disseminated

to other tissues and body fluids, including saliva, urine, and

feces. During this phase, the virus localizes and damages hepatocytes

and endothelial cells. The cytotoxic effects of the virus cause

the initial cellular injuries in the liver, kidney, and eye.

In dogs, the hepatic necrosis which occurs during this stage

of infection may be self-limiting and restricted to centrilobular

areas. The reticulin framework of the liver remains intact, and

hepatic regeneration quickly follows with little evidence of

clinical disease. In cases with overt clinical signs, either

recovery or death occurs after several days of anorexia, apathy,

vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

-

- Because the virus is endotheliotrophic, widespread intimal

damage exposes the underlying subendothelial collagen initiating

diffuse activation of the clotting cascade with resultant consumption

of clotting factors and platelets. A hemorrhagic diathesis results,

and petechiae, ecchymoses, epistaxis and prolonged hemorrhage

from venipuncture sites may be observed clinically. Bleeding

into the brain occurs in a small percentage of cases, and some

sudden deaths in dogs may be caused by acute midbrain hemorrhage.

- In rare instances, a peracute form of the disease occurs,

and these severely affected dogs become moribund and die with

few, if any, clinical signs during initial viremia. The animal

is found dead, and owners often suspect poisoning as the cause.

This form of the disease in the dog is reminiscent of the clinical

history described for this skunk.

-

- Contributor: Wildlife Conservation Society, Department

of Pathology, 185th St. and Southern Blvd., Bronx, NY 10460.

-

- References:

- 1. Appel M: Canine adenovirus type I (infectious canine hepatitis).

In: Virus Infections of Carnivores, pp. 29-44, Elsevier Science

Publishers, New York, 1987.

- 2. Cabasso V: Infectious canine hepatitis. In: Infectious

Diseases of Wild Animals, Davis, Karstad, Trainer eds., pp. 191-195,

Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1981.

- 3. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by viruses.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 241-245, Williams and

Wilkins, Philadelphia, 1997.

- 4. Karstad LR, Ramsden R, Berry TJ, Binn LN: Hepatitis in

skunks caused by the virus of infectious canine hepatitis. J

Wild Dis 11:494-496, 1975.

- 5. Tizard I: Immune complexes and type III hypersensitivity.

In: Veterinary Immunology: An Introduction, 5th ed., pp.368-371,

WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1996.

- 6. Greene CE: Infectious canine hepatitis. In: Infectious

Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 22-27, WB Saunders

Co., Philadelphia, 1998.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #'s 17187-89; 16883.

-

- Case II - 8004-98 (AFIP 2640591)

Signalment: Canine, male, neutered, German Shepherd Dog,

six-year-old.

History: One week prior to euthanasia, this dog was examined

by a referring veterinarian for lethargy. Two days later, anterior

uveitis (OD) and posterior paresis were evident.

-

- Gross Pathology: Throughout the right kidney, but

particularly in the medulla, were small yellow-white foci. The

body of T13 was friable, yellow-tan, and dorsally displaced.

The T13/ L1 disk was absent. The body of L1 was rough and red.

-

- Laboratory Results: Spinal radiographs revealed collapse

of the T13/L1 intervertebral disk space with lysis and periosteal

bone proliferation of the T13 and L1 vertebral bodies. A myelogram

revealed compression of the spinal cord in this area. Cytology

of a fine-needle aspirate of the affected disk revealed fungal

hyphae and spores. Aspergillus terreus was isolated.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Kidney: Tubular-interstitial

nephritis, pyogranulomatous, with thromboangiitis, hemorrhage,

and numerous fungal elements (septate hyphae and spores).

-

- This case is an example of disseminated Aspergillus terreus

infection in a dog. German Shepherd Dogs are probably predisposed

to infection with this saprophytic fungus. In the kidney, the

medulla is usually affected more than the cortex. Vertebrae are

common sites of fungal localization. The pathogenesis obviously

involves hematogenous dissemination (mycethemia). In section,

Aspergillus terreus spores that branch laterally from septate

hyphae are termed aleuriospores.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

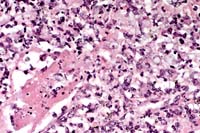

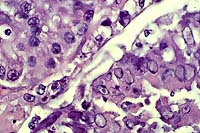

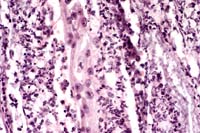

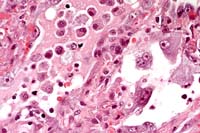

- Case 4-2. Kidney. There is multifocal liquefactive

necrosis of medullary collecting tubules characterized by an

infiltrate of neutrophils, histiocytes, and occasional faint

5-10µ yeasts.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

- Case 4-2. Kidney. Lumena of necrotic collecting tubules

are filled with pale fungal hyphae and surrounded by neutrophils

and fewer macrophages.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephritis, necrosuppurative,

multifocally extensive, severe, with necrotizing vasculitis and

numerous fungal hyphae, German Shepherd Dog, canine, etiology

consistent with Aspergillus sp.

-

- Conference Note: Aspergillus sp., common saprophytic

molds, are not usually pathogens, but cause opportunistic infections.

Aspergillosis is most common and severe in poultry, especially

chicks and turkey poults, where infection is due to contaminated

bedding and may occur as an epizootic with high mortality.

In people and cats, disseminated aspergillosis occurs most frequently

in hosts that are debilitated or immunosuppressed by a variety

of underlying conditions such as neoplasia (malignant lymphoma),

infectious agents (panleukopenia, FeLV, AIDS), and drug therapy

(glucocorticoids, prolonged antibiotic use). Disseminated canine

aspergillosis is a rare disease most often caused by Aspergillus

terreus. It occurs most commonly in German Shepherd Dogs. Predisposing

factors leading to disseminated aspergillosis in dogs may include

optimal environmental conditions for growth of the organism,

infection with particularly virulent fungal strains, and a genetically

based immunodeficiency, such as a defect in mucosal immunity

or defects in phagocyte or neutrophil function. Unlike disseminated

aspergillosis, nasal aspergillosis in the dog is most commonly

caused by A. fumigatus.

-

- The exact portal of entry for A. terreus is unknown, but

fungal conidia or aleuriospores may enter the host and establish

initial infection through the respiratory or gastrointestinal

tract. In man, infection follows inhalation of spores, and organisms

proliferate within previously diseased areas of the lung, such

as resolved tuberculosis lesions. Alternatively, some infections

may be initiated by surgery or intravenous inoculation. Once

entry is gained and infection is established, the ability of

the organism to invade and disrupt vessels allows hematogenous

spread via circulating aleuriospores. In section, aleuriospores

are lateral branching spherical vesicles occasionally found along

thin-walled fungal hyphae of A. terreus. The GMS method demonstrated

numerous aleuriospores in this case. These distinctive structures

allow specific histopathologic diagnosis of A. terreus infection.

-

- The distribution of gross lesions in this dog is similar

to the findings reported in a retrospective study of ten dogs

with disseminated aspergillosis. Lesions in these dogs frequently

developed in the kidneys, spleen, long bones, and the epiphyses

of vertebra and sternebra. Terminal capillary loops and slow

blood flow characterize these anatomical locations. The renal

medulla has numerous arteriolae rectae which terminate in capillary

loops, and may explain the predominate medullary distribution

of lesions in this dog. The organism's ability to invade and

disrupt vessels leads to activation of the coagulation cascade,

thrombosis, and infarction. Vascular stasis and thrombosis are

important in the development of osteomyelitis.

Conference participants discussed Fusarium sp. as another cause

of fungal nephritis. Fusarium is an environmental saprophyte

which may be found as a part of the normal microflora of the

canine skin. The organism has been reported as an infrequent

cause of mycotic disease in dogs, including cases of ascending

unilateral pyelonephritis in a Newfoundland and disseminated

disease in a German Shepherd. The organism in the Newfoundland

occurred as dense mycelial mats of branching septate fungal hyphae

with occasional terminal globose heads; aleuriospores were not

described. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the identity of the

organism.

Contributor: Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, ADDL-1175,

Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907.

-

- References:

- 1. Kabay MJ, Robinson WF, Huxtable CRR, McAleer R: The pathology

of disseminated Aspergillus terreus infection in dogs. Vet Pathol

22:540-547, 1985.

- 2. Day MJ, Holt PE: Unilateral fungal pyelonephritis in a

dog. Vet Pathol 31:250-252, 1994.

- 3. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by fungi.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 506-507, Williams and

Wilkins, 1997.

- 4. Day MJ: Canine disseminated aspergillosis. In: Infectious

Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 409-412, WB Saunders

Co., Philadelphia, 1998.

- 5. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL: Infectious diseases. In:

Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 5th ed., pp. 355-356, WB

Saunders Co., 1994.

-

- Case III - Fac. Med. Vet. da USP 2 (AFIP 2641266)

-

- Signalment: Adult, male, howler monkey, Alouatta fusca,

Cebidae, New World non-human primate.

-

- History: This free-ranging howler monkey was kept

in captivity for six months due to an ongoing reintroduction

program. During this period, the animal was identified with a

microchip and submitted to multiple serological assays, including

rabies, leptospirosis, malaria and Lyme disease, and periodical

clinical examination. After this period, the monkey was released

in a remaining tropical rain forest close to São Paulo

City. Ten days after reintroduction to the wild, it was found

in an agonal state due to a dog attack.

-

- Gross Pathology: Grossly, the howler monkey presented

with extensive multifocal hemorrhages associated with dog bites.

Within the oral cavity, there were multiple, two to five millimeter

diameter, soft, white, isolated to coalescing masses which affected

the mucosa of the lower lip and the craniomedial aspect of the

tongue. Other major findings were pulmonary edema, typhlitis

due to Enterobius sp., and multifocal ulcerative colitis.

-

- Laboratory Results:

- 1. Heart blood cultures: Negative.

2. Liver cultures: Negative.

3. Serological essays for rabies, malaria, Lyme disease, leptospirosis:

Negative.

4. Immunohistochemistry assays for papillomavirus (polyclonal

antibody-DAKO ä, dilution 1:8000): Positive.

5. Immunohistochemistry assays for human papillomavirus types

6, 11, 18 (monoclonal antibody NOVOCASTRAä, dilution 1:40):

Negative.

6. In situ hybridization for detection of DNA of human papillomavirus

types 6, 11, 16, 18, 30, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51 and 52 (DAKOä):

Negative.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Mucosa, lower

lip: Acanthosis, moderate, associated with marked koilocytosis,

fusion of rete ridges, and minimal hyperparakeratosis (Focal

Epithelial Hyperplasia, FEH - Heck's Disease) due to papillomavirus,

howler monkey (Alouatta fusca), Cebidae, New World non-human

primate.

-

- Focal Epithelial Hyperplasia (FEH), also known as Heck's

disease, is an uncommon condition, occurring only in the oral

cavity, and related to papillomavirus infection. It has been

described in humans (South, Central, and North American Indians

and Eskimos), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), pygmy chimpanzees

(Pan paniscus) and the domestic rabbit. FEH has never been reported

in New World Primates.

Grossly, FEH is defined as well-circumscribed or coalescing,

slightly elevated, soft masses or papules, 0.1 to 0.5 cm in diameter,

affecting mainly the lower lip and buccal mucosa. Lesions are

usually white to pink. Microscopically, FEH is mainly characterized

by mild to severe focal acanthosis associated with elongation

and fusion of the rete ridges and keratinocyte vacuolization

(koilocytosis).

In humans, in situ DNA hybridization exams revealed that human

papillomavirus types 13 and 32 are markedly specific for FEH.

In non-human primates, molecular biology assays were performed

in the pygmy chimpanzee, revealing the presence of an agent related

to HPV-13, tentatively named pygmy chimpanzee papillomavirus.

In the present case, the gross and microscopic features are in

accordance with those described in the literature for FEH. The

nature of the viral antigen was determined using a rabbit polyclonal

antibody to bovine papillomavirus. Subsequent immunohistochemistry

assays for HPV and in situ HPV DNA hybridization exams were negative,

suggesting the possibility that the agent is not related to the

known papillomaviruses. Further studies are planned to clarify

this possibility.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

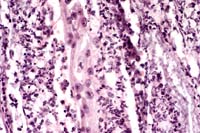

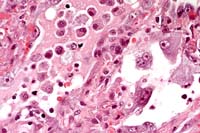

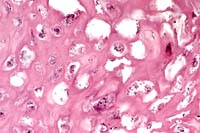

- Case 4-3. Lip. There is proliferation and ballooning

degeneration of the acanthocytes. Within the clear cytoplasm

are numerous minute, granular inclusions. (The surface is to

the right).

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Oral mucosa, epithelium: Hyperplasia,

diffuse, severe, with numerous koilocytes, vacuolar degeneration,

and few intranuclear inclusions, howler monkey (Alouatta fusca),

nonhuman primate.

-

- Conference Note: Papillomaviruses are a large, heterogenous

group of small, double-stranded DNA viruses noted for their ability

to induce epithelial proliferation. Papillomaviruses are usually

species and target cell specific.

-

- The term multifocal papilloma virus epithelial hyperplasia

(MPVEH) has been suggested as a more appropriate name for FEH

because it describes the nature and pathology of the disease.

Microscopically, the lesions are characterized by acanthosis

of the mucosal epithelium, anastomosing rete ridges which often

point radially toward the center of the lesion, parakeratotic

hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration of keratinocytes. Within

the hyperplastic basal layers of the epithelium, a few keratinocytes

may be swollen with abundant clear cytoplasm and contain an irregularly

enlarged nucleus with central amphophilic to basophilic granularity.

The nuclear changes are highly diagnostic for MPVEH in humans.

In this howler monkey, rare basal epithelial cells demonstrate

similar histologic changes. The term "mitosoid" has

previously been applied to the nuclear changes in human lesions;

however, the term is confusing, may lead to erroneous interpretations,

and should be avoided.

-

- Explanations for the epidemiological distribution of human

disease noted by the contributor are varied, and several socioeconomic

and genetically based hypotheses have been proposed. Papillomaviruses

may demonstrate a viral site specificity for infection, and this

mechanism is proposed for MPVEH and HPV32. The site of viral

specificity is dependent on the numbers and distribution of cell

membrane receptors. Affected families or ethnic groups may have

higher numbers of these cell receptors and thus a greater likelihood

of infection. It has also been observed that MPVEH often affects

individuals in lower income groups, suggesting that malnutrition,

chronic immunodeficiency, and poor hygiene may correlate with

risk of infection and disease transmission.

-

- Several DNA and RNA viruses are known to be oncogenic in

humans and animals. Human papillomaviruses are involved in the

genesis of a variety of epithelial tumors in man, including benign

squamous papillomas as well as squamous cell carcinoma of the

cervix and anogenital region. The oncogenic properties of papillomaviruses

are related to products of two early papillomaviral genes, E6

and E7.

-

- The E7 viral protein binds to the cellular tumor suppressor

gene retinoblastoma protein (Rb). This affects the ability of

the Rb gene product (pRb) to bind and sequester cellular transcription

factors involved in the initiation of DNA synthesis. With these

transcription factors liberated from pRb, the molecular controls

on the cell cycle are released, DNA synthesis is triggered, and

the normally quiescent cells quickly reenter the cell cycle resulting

in indiscriminate proliferation.

-

- The E6 protein binds to and inactivates p21, the product

of the cellular tumor suppressor gene p53. Normally, when cellular

DNA is damaged, as occurs in viral infections or due to mutagenic

chemicals, p53 accumulates in the nucleus and acts by inducing

the transcription of p21. When functional, p21 protein is a potent

inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinase system (it inhibits

the formation of cyclin/CDK complexes) and blocks the phosphorylation

pRb. The pRb protein remains in the active, unphosphorylated

state, thus preventing the cell from entering the S phase of

the cell cycle. This pause in the cell cycle allows for repair

of damaged cellular DNA. With inactivation of p21 protein, cells

with damaged DNA are allowed to reenter the cell cycle and proliferate

without proper repair, thus leading to potential oncogenesis.

-

- Both the p53 gene and Rb gene act in the nucleus and work

by inhibiting the cell cycle. Unlike the Rb gene, however, p53

does not continually police the normal cell, but is activated

during periods of damage to cellular DNA. Should the DNA repair

mechanisms fail, the p53 gene stops the cell from dividing and

activates the cell-suicide genes in the process known as apoptosis.

Apparently, papillomaviruses may act to prevent this fail safe

mechanism of p53, and uncontrolled, sometimes malignant proliferation

of virally infected cells occurs.

-

- Contributor: University of São Paulo, Faculty

of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechny, Department of Pathology,

Av. Prof. Orlando Marques de Paiva 87, Cidade Universitária,

São Paulo SP 05508-900, Brazil.

References:

- 1. Anderson DC, McClure HM: Focal epithelial hyperplasia,

chimpanzees. In: Monographs on Pathology of Laboratory Animals:

Nonhuman Primates, Jones, Mohr, Hunt eds., pp. 233-237, Springer-Verlag,

New York, 1993.

- 2. Viraben R, et al.: Focal Epithelial Hyperplasia (Heck

disease) associated with AIDS. Dermatology 193:261-262, 1996.

- 3. Van Ranst M, et al.: A papillomavirus related to HPV type

13 in oral focal epithelial hyperplasia in the pygmy chimpanzee.

J Oral Pathol Med 20:325-321, 1991.

- 4. Roman CB, Sedano HO: Multifocal papilloma virus epithelial

hyperplasia. J Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 77:631-635, 1994.

- 5. Kumar V, Cotran RS, Robbins SL: Neoplasia. In: Basic Pathology,

6th ed., pp.153-167, WB Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1997.

-

- Case IV - 568-94 (AFIP 2639850)

- Signalment: Nine-year-old, adult, female leopard cat

(Felis bengalensis).

- 2 histology images (previously improperly labeled 4-1)

-

- History: This animal had no history of current medical

problems. The keeper reported she had eaten her dinner normally

the night before. The following morning, she exhibited respiratory

distress. With handling, the dyspnea progressed to respiratory

arrest, and the cat died shortly after intubation.

Gross Pathology: The lungs were firm and mottled, and

the right anteroventral lobe was plum colored. The trachea contained

moderate amounts of blood-tinged foam. There were no other gross

lesions. A lung swab was submitted for bacterial culture. Tissues

were frozen at minus 70o C.

-

- Laboratory Results: Viral isolation of the lung tissue

was positive for feline herpesvirus. Aerobic bacterial cultures

of the lung had no growth. Immunoperoxidase staining for toxoplasmosis

was negative.

-

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: 1. Bronchi and

bronchioles: Bronchitis and bronchiolitis, subacute, necrotizing,

multifocally extensive, moderate to severe, with extension into

alveolar tissue, and intraepithelial intranuclear inclusion bodies

(feline herpesvirus Type I). 2. Alveolar edema and emphysema,

multifocally extensive, moderate to severe. 3. Peribronchiolar

glands: Hyperplasia, moderate.

-

- Feline viral rhinotracheitis (FVR) is an infection of all

Felidae and is caused by feline herpesvirus type I (FHV-1), a

member of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily of Herpesviridae.1,3,6

The first documented isolation of the FVR virus in an exotic

felid was reported at the St. Louis Zoo in 1977 where it caused

the deaths of three out of five clouded leopards (Felis nebulosa)

in a single outbreak.

-

- In domestic cats, infection with FHV-1 accounts for 40 to

50% of all upper respiratory diseases.1 The virus has a predilection

for the epithelium of nasal passages, pharynx, soft palate, conjunctivae,

tonsils, and, to a lesser extent, trachea.4 Clinical signs correspond

to these sites of viral replication and consist of paroxysmal

sneezing, coughing, salivation, fever, and serous to mucopurulent

nasal and conjunctival discharges.4 Although morbidity is quite

high, most cats recover within two weeks with supportive care.

Many of these cats become asymptomatic carriers and may shed

virus at later times of stress.

- This leopard cat had an unusual presentation. No lesions

were found in the nasal passages, oral cavity, tonsils, or conjunctivae.

Histologic lesions were limited to the lower respiratory tract

and centered on the bronchi and bronchioles with extension into

the adjacent alveolar tissue. As viral inclusions were not identified

in the initial sections, other causes of feline respiratory disease

were considered including feline calicivirus, feline reovirus,

the feline-adapted strain of Chlamydia psittaci (feline pneumonitis

agent), Mycoplasma felis, Bordetella bronchiseptica and Pasteurella

multocida. However, bacterial cultures and Giemsa stains for

Chlamydia were negative. Immunoperoxidase staining for toxoplasmosis

was also negative. Additional recuts of lung tissue revealed

smudgy to clearly distinct intranuclear inclusion bodies in sloughed

bronchiolar epithelial cells. Tissue was submitted for viral

isolation and was positive for feline herpesvirus.

-

- As was the case in the St. Louis outbreak, there was no identifiable

source of exposure of the cats to the virus. No management changes

(i.e., shipment, handling, change of enclosures) had occurred

for an extended period of time before the disease onset. The

most likely explanation in these cases is that there was a recrudescence

of a latent infection. Although in domestic cats subsequent infections

are usually less severe than the initial infection, this may

not be true of exotic felids. Many zoos now vaccinate on a six

month basis due to the high mortality rate.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

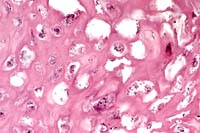

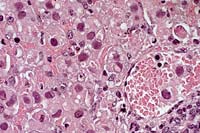

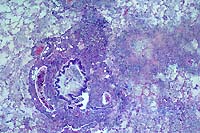

- Case 4-4. Lung. There is proliferation of type II

pneumocytes. Alveoli are filled with macrophages, fewer lymphocytes

and edema and occasionally contain syncytia. Alveolar septae

are thickened by fibrin, histiocytes and large pneumocytes.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, bronchointerstitial,

necrotizing, acute to subacute, diffuse, with alveolar edema,

few syncytial cells, and numerous amphophilic and eosinophilic

intranuclear inclusions, leopard cat (Felis bengalensis), feline.

-

- Conference Note: Herpesviruses infect a wide variety

of animals from insects through vertebrates, and with the possible

exception of sheep, a herpesvirus is the cause of at least one

major disease in each of the domestic species. Herpesviruses

are classically divided into three subfamilies: a-herpesvirinae,

b-herpesvirinae, and g-herpesvirinae. Generally, the a-herpesvirinae

are rapidly growing, cytolytic viruses that have the ability

to establish latent infections in nerve ganglia (especially the

trigeminal), and may have a broad host range. Examples are numerous

but include infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, coital exanthema

of equids, duck plague, and pseudorabies. The cytomegaloviruses,

or b-herpesvirinae, have a restricted host range, slow viral

replication which does not cause cell lysis until several days

after infection, and may remain latent in secretory glands, lymphoreticular

tissue, kidneys, and other tissues. A few examples include equine

cytomegalovirus infection (EHV-2) and inclusion body rhinitis

of swine (porcine herpesvirus-2). The final group, the g-herpesvirinae,

are known for their predilection to infect and remain latent

within lymphoid cells, though they may cause cytocidal infections

in epithelial and fibroblastic cells. Classic examples include

Epstein-Barr virus in man and malignant catarrhal fever of bovids

(Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1).

-

- Feline rhinotracheitis virus (FRV) is a typical a-herpesvirus

that measures between 120-200nm (average 150nm), contains double-stranded

DNA, replicates in the cell nucleus, and becomes enveloped by

budding through invaginations of the nuclear membrane. Infection

with FVR is naturally acquired through oral, nasal or conjunctival

routes by either direct contact or from aerosolized oronasal

secretions of virus-shedding infected cats. After an incubation

of 24-48 hours, the onset of typical clinical signs of an upper

respiratory tract infection occurs, accompanied by profuse salivation

and corneal ulcers. While oral ulceration may also be present

in FVR, this lesion is more typical of feline calicivirus infections.

-

- Viral replication occurs primarily in the epithelium of nasal

cavity, nasopharynx, turbinates, and in the tonsils. Shedding

of viral particles may begin as early as 24 hours post infection

and may last as long as one to three weeks, though most active

viral replication and cell necrosis occur between two to seven

days post infection. During this period, the herpesviral intranuclear

inclusions are most often present in infected epithelial cells

and occasionally within endothelial cells. Because viral replication

is normally restricted to areas of lower body temperature, such

as the upper respiratory passages, viremia is rare, and resolution

of disease normally takes between two to three weeks.

-

- Uncommonly, generalized disease may follow initial upper

respiratory tract infection in debilitated or immunocompromised

animals and in neonatal kittens. In these cases viremia may be

present. Mortality due to FVR is rare in domestic cats, but when

fulminating cases of viral infection occur, there is often widespread

necrotizing bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and interstitial pneumonia

with edema. Viral infection may predispose to fatal secondary

bacterial bronchopneumonia.

-

- Contributor: Wildlife Conservation Society, Department

of Pathology, 185th St. and Southern Blvd., Bronx, NY 10460

-

- References:

- 1. Baldwin CA: Feline Viral Rhinotracheitis. In: Veterinary

Diagnostic Virology, Castro, Heuschele eds., pp. 189-191, Mosby

Year Book, St. Louis, 1992.

- 2. Boever WK, McDonald S, Solorzand RF: Feline viral rhinotracheitis

in a colony of clouded leopards. Veterinary Medicine/Small Animal

Clinician Exotic Species. December 1977:1859-1866.

- 3. Fowler ME: Carnivores. In: Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine,

2nd ed. , pp.834-836, 1986.

- 4. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N: The respiratory system.

In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., vol. 2, pp. 558-559,

Academic Press, 1993.

- 5. Pedersen NC: Feline herpesvirus type I (feline rhinotracheitis

virus). In: Virus Infections of Carnivores, Appel ed., Vol. 1,

pp. 227-237, Elsevier Science Publishers, 1987.

- 6. Wallach JD, Boever WJ: Diseases of Exotic Animals. In:

Medical and Surgical Management, pp. 368-369, WB Saunders Company,

Philadelphia, 1983.

- 7. Gaskell R, Dawson S: Feline respiratory disease. In: Infectious

Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 97-106, WB Saunders

Co., Philadelphia, 1998.

- 8. Fenner FJ, et al.: Herpesviridae. In: Veterinary Virology,

2nd ed., pp. 337-368, Academic Press Inc., San Diego, 1993

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #'s 4877 and 15417.

-

- Ed Stevens, DVM

Captain, United States Army

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: STEVENSE@afip.osd.mil

-

- * The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

Return to WSC Case Menu

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.

40x

Obj.