Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 3

16 September 1998

- Conference Moderator:

COL Nancy Jaax, Diplomate, ACVP

Pathology Division

U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Disease

Ft. Detrick, Frederick, MD 21702-5011

NOTE: Click on images for larger views. Use

browser's "Back" button to return to this page.

Return to WSC Case Menu

Case I - 9735768 (AFIP 2639843)

-

- Signalment: Eleven-year-old, male, domestic shorthair,

feline.

-

- History: One large focal mass was noticed within the

skin and underlying subcutaneous tissues of the caudal dorsal

midline by the owner. An excisional biopsy was performed by the

referring veterinarian.

-

- Gross Pathology: One large focal tan mass, approximately

2.5 cm in diameter, was submitted for histologic examination.

-

- Laboratory Results: Cultures of the mass were positive

for Blastomyces dermatitidis.

-

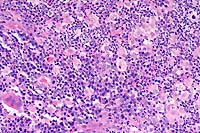

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Severe focal

ulcerative pyogranulomatous mycotic dermatitis, cellulitis, and

myositis (blastomycosis), caudal dorsal midline.

-

- Etiology: Blastomyces dermatitidis.

-

- The histologic appearance of the section of skin and underlying

tissues is characterized by severe epidermal ulceration and large

accumulations of neutrophils intermixed with macrophages, plasma

cells, lymphocytes and epithelioid cells within the dermal and

subcutaneous tissues which extend into the underlying skeletal

musculature. Numerous spherical to slightly ovoid, thick, double

contoured walled organisms are also evident within the inflammatory

cell accumulations. Occasional organisms displaying broad based,

single budding are noted in some sections. Large, multifocal

to coalescing areas of necrosis are also evident scattered throughout

the tissues. The lesions extend to the edges of many of the sections.

-

- Blastomycosis is primarily a disease of humans and dogs but

can be seen in other animals, including the cat and horse. Blastomyces

dermatitidis, the causative agent of North American blastomycosis,

is a dimorphic fungus which produces a mycelial growth at room

temperature and yeast-like forms in tissue and culture at 37

degrees Celsius. The organism reproduces by budding and can be

found free or within macrophages in affected tissues. Although

the lung is considered the most common site of primary involvement,

primary cutaneous infections can also occur. The pulmonary form

of the disease has a chronic course characterized by exercise

intolerance and coughing. Systemic dissemination can occur with

lesions found within the lymph nodes, skin, eyes, central nervous

system, subcutaneous tissues, bones, joints, urogenital system

and other organs. Cutaneous lesions begin as small papules and

progressively develop into granulomas or pyogranulomas.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.  GMS

40x obj.

GMS

40x obj.

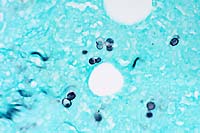

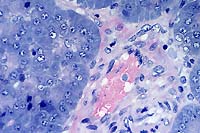

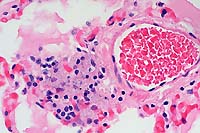

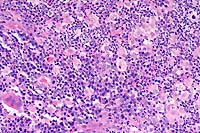

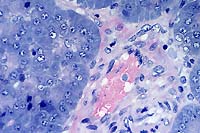

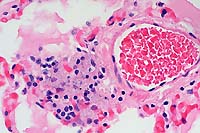

- Case 3-1. Haired skin. Diffusely (here, Left, 20x

obj) replacing normal dermal elements, there is an cellular infiltrate

composed of high numbers of neutrophils, fewer epithelioid macrophages,

lymphocytes, and plasma cells with rare foreign body type giant

cells (lower left). There are rare 15-20u diameter oval yeast

bodies with a basophilic central zone surrounded by a clear eccentric

halo (upper right). Gomori Methenamine Silver (Right, GMS 40x

obj) staining highlights yeast bodies which are occasionally

forming broad based buds.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin and subcutis: Dermatitis

and panniculitis, pyogranulomatous, diffuse, severe, with ulceration,

acanthosis, furunculosis, and yeast-like organisms, Domestic

Shorthair, feline, etiology consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis.

-

- Conference Note: Blastomycosis is usually acquired

by inhalation of spores from the environment. The organism establishes

a primary infection in the lung, and becomes disseminated most

commonly to the lymph nodes, skin, eyes, bone, subcutaneous tissues,

external nares, brain and testes via the vascular and lymphatic

system. Less commonly, dissemination may occur to nasal passages,

mouth, prostate, liver, mammary gland, vulva, and heart. Occasionally,

primary cutaneous infection may occur from a puncture wound in

the skin. Such skin lesions begin as papules and develop into

abscesses. As the abscesses expand, the center undergoes cicatrization.

Because skin lesions more commonly result from disseminated infection,

cutaneous blastomycosis should arouse suspicion of systemic disease.

Lung lesions sometimes resolve by the time the sites of disseminated

infection become apparent.

-

- Soil is thought to be the reservoir for B. dermatitidis.

Four key environmental factors have been epidemiologically associated

with infection. These are moisture; sandy, acidic soil with organic

debris; disruption of the soil; and the presence of wildlife.

Most cases of blastomycosis occur along waterways. Many infections

are associated with sandy, acidic soil and organic debris, and

the disruption of soil may be caused by earth moving equipment

or landscaping. The presence of wildlife, particularly beavers

and waterfowl and their excreta, is also believed to play a part

in the occurrence of disease. In these environments, the organism

grows as a saprophytic mycelial form that produces infective

spores. At body temperatures, the organism transforms from the

mycelial form to the yeast form under the control of its bys-1

gene.

-

- As noted by the contributor, blastomycosis is most common

in dogs and people, but cats, horses, sea lions, wolves, ferrets,

dolphins and polar bears have also developed the disease. In

cats, pulmonary, cutaneous, and systemic forms occur. There does

not seem to be breed, age, or sex predisposition. In dogs, however,

sex and breed predispositions have been noted. Male dogs are

more frequently infected than females, and a greater percentage

of females with equally severe disease survive treatment. Sporting

dogs and hounds are at greater risk, probably due to more frequent

outdoor activity than other breeds. In general, young (one to

five-year-old), male, large breed dogs are most commonly infected.

In the southeast United States, occurrence is not seasonal, but

in other areas of the U.S., most cases occur from the late spring

through late autumn.

-

- A differential diagnosis that included cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis,

aspergillosis, coccidiomycosis, African histoplasmosis and South

American blastomycosis was considered by the conference attendees.

In tissue, Blastomyces dermatitidis occurs as 8-15 micron diameter,

spherical to oval, multinucleate, yeast-like cells, with thick,

doubly contoured, refractile walls and single, broad-based buds.

Coccidiodes immitis is larger, and reproduces by endosporulation

rather than budding. Histoplasma capsulatum is much smaller than

Blastomyces, and has narrow-based budding. Histoplasma capsulatum

var. duboisii (African histoplasmosis) may be confused with Blastomyces

dermatitidis, but the former has narrow-based buds and do not

contain multiple nuclei. Cryptococcus neoformans is characterized

by a wide, carminophilic capsule. Aspergillus organisms often

occur as radiating hyphae that branch dichotomously at acute

angles. Paracoccidiodes braziliensis, the cause of South American

blastomycosis, reproduces in tissue by multiple budding.

-

- Contributor: Animal Diagnostic Laboratory, Pennsylvania

State University, University Park, PA 16802.

-

- References:

- 1. Cote E, Barr SC, Allen C, Eaglefeather E: Blastomycosis

in six dogs in New York

state. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 210(4):502-504, 1997.

- 2. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N: The respiratory system.

In: Pathology of

Domestic Animals, 4th ed., vol. 2, pp. 667, Academic Press, 1993.

- 3. Carter GR, Cole Jr. JR: In: Diagnostic Procedures in Veterinary

Bacteriology and Mycology. 5th ed., pp. 442-446, Academic Press,

1990.

- 4. Breider MA, Walker TL, Legendre AM, van Ee RT: Blastomycosis

in cats: five cases (1979-1986). J Amer Vet Med Assoc 193(5):570-572,

1988.

- 5. Nasisse MP, van Ee RT, Wright B: Ocular changes in a cat

with disseminated blastomycosis. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 187(6):629-631,

1985.

- 6. Legendre AM: Blastomycosis. In: Infectious Diseases of

the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 371-377, WB Saunders Co., 1998.

- 7. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases caused by fungi.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 505-547, Williams and

Wilkins, 1997.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #'s 12365-12367.

-

Case II - A96359034 (AFIP 2639019)

-

- Signalment: Two-week-old, female Labrador Retriever.

-

- History: Two puppies from a litter of seven became

acutely ill with diarrhea ranging from bloody to mucoid. In one

of the puppies, there was severe abdominal cramping.

-

- Gross Pathology: Acute pulmonary congestion and edema.

Ileal serosal petechiation.

Laboratory Results:

Bacterial cultures:

1. Bitch's milk: Staphylococcus intermedius.

2. Puppy lung & intestine: E. coli.

-

- Virology: Electron microscopy of puppy intestinal

contents positive for parvovirus.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Enteritis, acute,

necrotizing with enterocyte intranuclear inclusions. Etiology:

Minute virus of canines (parvovirus).

Additional lesions present in the puppy were multifocal hepatic

necrosis and interstitial pneumonia with intravascular colonies

of small gram-negative bacilli suggesting an acute superimposed

bacteremia. Lymphoid necrosis in Peyer's patches and mesenteric

lymph nodes was attributed to the viral infection.

Two distinct parvoviruses are known to infect dogs. Canine parvovirus-type

1 (minute virus of canines) infection seems to be fairly widespread,

but clinical disease is uncommon. Canine parvovirus-type 2 infection,

first recognized in 1978, is also widespread, and infection commonly

results in severe disease with high mortality. The viruses differ

in antigenicity and tissue tropism.

Clinical disease due to CPV-1 can result from in utero infection

early in gestation with embryonic/fetal death. In utero infection

late in gestation results in the birth of normal puppies. Infection

in puppies generally less than three weeks of age can result

in clinical disease, but factors relating to clinical disease

versus inapparent infection are unknown. Clinically, the disease

is manifest as vomiting, diarrhea, crying, and dyspnea. Histologically,

the lesions affect primarily small intestine and lymphoid tissues.

In the small intestine, intranuclear inclusion bodies occur at

or near the villous tips with sloughing but minimal necrosis

of epithelial cells. Hyperplasia of crypt and villous epithelium

may also be noted. Necrosis and/or depletion of lymphocytes occur

in lymphoid tissues. According to one report, the Walter Reed

canine cell line is the only one that supports replication of

the CPV-1.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

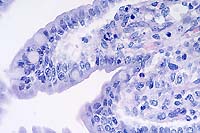

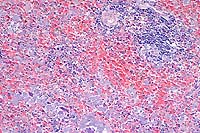

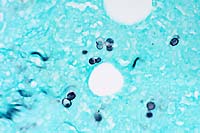

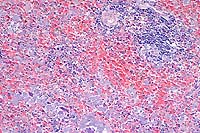

- Case 3-2. Small intestine. Demonstrates villous fusion,

swelling of mucosal epithelial cells, and multiple brick-shaped

amphophilic intranuclear inclusions.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

- Case 3-2. Lymph node. There is lymphoid depletion

of the paracortex, loss of follicular definition, and scattered

karyorrhexis of lymphoid cell nuclei (necrosis).

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

- Case 3-2. Pancreas. Multifocally within a blood vessel

there are clusters of small bacilli.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis:

- 1. Small intestine: Enteritis, subacute, diffuse, mild, with

multifocal villar fusion, multifocal epithelial necrosis, and

numerous, villar tip, epithelial intranuclear inclusions, Labrador

Retriever, canine.

- 2. Lymph node; Peyer's patches: Lymphoid necrosis, diffuse.

- 3. Pancreas: Bacilli, intravascular and multifocal.

-

- Conference Note: Canine parvoviruses are small (20

nm diameter), nonenveloped, single-stranded DNA viruses that

require rapidly dividing cells, such as bone marrow cells, intestinal

epithelium, and lymphoid cells, for replication. Parvoviruses

are extremely stable and resistant to both adverse environmental

conditions and most common detergents and disinfectants, with

the exception of sodium hypochlorite (household bleach).

-

- The domestic dog is the only proven host for CPV-1, although

other canids are probably susceptible. Serologic evidence suggests

that it has a widespread distribution in the dog population,

but clinical disease is generally restricted to pups less than

three weeks old. Natural disease develops in these young pups

through oronasal exposure or in utero infection and causes enteritis,

mild pneumonia, and occasional myocarditis or sudden death. Because

of the limited number of reported cases, the clinical importance

of CPV-1 infection is not completely known.

Histologically, the intestinal lesions produced by CPV-1 infection

are remarkably different from those of CPV-2 enteritis. CPV-2

infection results in loss of normal villar architecture, collapse

of the mucosa, extensive blunting and fusion of villi, and often

severe crypt epithelial necrosis. Epithelial intranuclear inclusions

are uncommonly observed. In contrast, relatively normal villar

architecture is maintained in CPV-1 infection, and there is crypt

epithelial hyperplasia. Villar epithelial cells are often vacuolated

and contain numerous intranuclear inclusions, and there may be

a mild inflammatory infiltrate.

-

- Several other histologic lesions may occur in parvoviral

infections. Varying degrees of lymphoid necrosis and depletion,

both within Peyer's patches and lymph nodes, are described in

both types of parvovirus infection. Interstitial pneumonia, bronchitis,

pneumonitis, and the presence of intranuclear inclusions within

the bronchiolar epithelium can occur with CPV-1, and are especially

associated with experimental infections. Infrequently, a nonsuppurative

myocarditis may occur in CPV-1 infection, and varying histologic

lesions have been described including interstitial edema, infiltration

by mononuclear inflammatory cells, myocardial necrosis and mineralization,

and occasionally the presence of intranuclear inclusions within

myocardiocytes.

-

- Gross lesions in infected puppies are often mild. In experimental

infections, lesions noted included red-gray consolidation of

ventral and hilar areas of the apical and cardiac lobes of the

lung, and bronchial and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Lesions

in natural infections vary and include enlarged lymph nodes,

streaking of the myocardium, atelectatic lungs, and soft, pasty

stools in the intestinal tract. The disease may cause stillbirths

or the birth of weak pups in infected bitches.

-

- Minute virus of canines may cause spontaneous disease in

young pups. Failure to subject stillborn or neonatal pups to

pathologic study may be the cause for the lack of reports. Pneumonia

and enteritis, and occasionally myocarditis, characterize the

pathological finidings in CPV-1 infection. The virus may provoke

only mild or vague signs, and fatal cases may be diagnosed as

"fading pups". Minute virus of canines should be considered

in the differential diagnosis for pups that die when less than

three weeks of age and in cases of failure to conceive or fetal

death.

References:

- 1. Barker IK, van Dreumel AA, Palmer N: The alimentary system.

In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., Jubb, Kennedy, Palmer

eds., vol. 2, pp. 141-199, Academic Press, 1993.

- 2. Carmichael LE, Schlafer DH, Hashimoto A: Pathogenicity

of minute virus of canines (MVC) for the canine fetus. Cornell

Vet 81:151-171, 1991.

- 3. Harrison LR, Styer EL, Pursell AR, Carmichael LE, Nietfeld

JC: Fatal disease in nursing puppies associated with minute virus

of canines. J Vet Diag Invest 4:19-22, 1992.

- 4. Macartney L, et. al.: Characterization of minute virus

of canines (MVC) and its pathogenicity for pups. Cornell Vet

78:131-145, 1988.

- 5. Hoskins JD: Canine viral enteritis. In: Infectious Diseases

of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 40-46, WB Saunders Co., 1998.

-

- Contributor: Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab,

P.O. Box 3200, Amarillo, Texas 79116-3200.

-

-

Case III - D96 3803 (AFIP 2642051 [corrected])

-

- Signalment: Eleven-year-old, male, neutered Domestic

Longhaired cat.

-

- History: This cat had fever of 105.8 and did not respond

to enrofloxacin or dexamethasone. He then became lethargic, shocky

and died.

-

- Gross Pathology: None described.

Laboratory Results: None.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Splenitis, histiocytic,

diffuse, severe, with numerous intracellular protozoal organisms,

characteristic of Cytauxzoon.

-

- Etiology: Cytauxzoon felis.

There are many intravascular and extravascular macrophages in

the spleen filled with schizonts characteristic of Cytauxzoon

felis infection. Cytauxzoon felis is classified in the family

Theileriidae. It is transmitted by ixodid ticks and is not contagious

by direct contact exposure. The bobcat is a natural host. Cats

infected with Cytauxzoon felis develop signs of anemia, icterus,

pyrexia, and depression. Early diagnosis of this disease can

be achieved by examination of peripheral blood for erythroparasitemia.

Cytauxzoon felis trophozoites are ring-forms and present within

the cytoplasm of erythrocytes. This differs from feline infectious

anemia caused by Hemobartonella felis in which the organisms

are coccoid and present on the surface of red blood cells. Cytauxzoonosis

is fatal in cats, and so far there is no drug available for the

treatment of this disease.

-

10x

obj.

10x

obj.

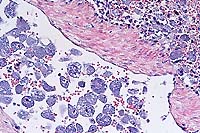

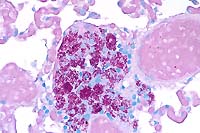

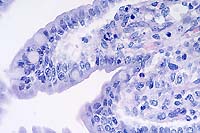

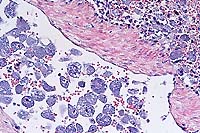

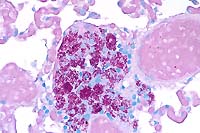

- Case 3-3. Spleen. There is little white pulp, and

here it is predominantly around a small arteriole. Multifocally

within the red pulp and vascular sinuses, there are abundant

ill defined large granular basophilic cells (interpreted as macrophages).

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

- Case 3-3. Spleenic artery. Within the splenic arteries

there are abundant large 20-30u cells with granular cytoplasm,

open faced nuclei and a single prominant nuclei (interpreted

as macrophages containing protozoal organisms). Similar macrophages

are scattered around the artery in the red pulp.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis: Spleen: Histiocytosis, intravascular

and diffuse, moderate, with intrahistiocytic protozoal schizonts,

Domestic Longhair, feline, etiology consistent with Cytauxzoon

felis.

-

- Conference Note: Most conference participants preferred

the diagnosis of splenic histiocytosis over splenitis based upon

the lack of histological changes associated with inflammation.

The lesion is characterized by an infiltrate composed almost

entirely of histiocytes that are filled with basophilic organisms

(schizonts), but there is lack of other inflammatory cells and

vascular changes that normally characterize an inflammatory process.

Cytauxzoon is classified in the order Piroplasmida and family

Theileriidae. This family has both an erythrocytic and a tissue

(leukocytic) phase. Large schizonts of C. felis develop in macrophages,

whereas in Theileria the exoerythrocytic stage occurs primarily

within lymphocytes. The Babesiidae, a related family, is characterized

by having a primarily erythrocytic phase in the mammalian host,

and its morphological features are indistinguishable from the

erythrocytic form of Cytauxzoon. Cytauxzoon felis, B. equi, and

B. rodhaini have been linked to both the babesias and theilerias

by RNA gene sequence analysis, and it has been suggested that

these organisms be reclassified within a separate family.

Ticks are implicated as the natural vector for Cytauxzoon, because

most cases of infection have been associated with the presence

of these parasites on the hosts. Experimentally, Dermacentor

variabilis can transmit the organism from bobcats to domestic

cats. In a white tiger that developed a natural, fatal infection

in Florida, two female Lone Star ticks (Amblyomma americanum)

were present on the inguinal skin. In the life cycle of C. felis,

schizonts develop within mononuclear phagocytes, initially as

indistinct vesicular structures and later as large, distinct

nucleated schizonts that actively undergo division by true schizogony

and binary fission. Later in the course of the disease, schizonts

develop buds (merozoites) that separate and eventually fill the

entire host cell. The host cell probably ruptures, releasing

merozoites into the tissue fluid and blood. Merozoites are then

believed to enter erythrocytes to form the intraerythrocytic

stage. Merozoites appear in macrophages one to three days before

they are observed in erythrocytes.

-

- Clinically, the disease in cats is characterized by fever,

depression, dyspnea, anorexia, lymphadenopathy, anemia, and icterus

leading to death in three to six days. Gross findings include

pale or icteric mucous membranes, petechiae and ecchymoses in

the lung, heart, lymph nodes and on mucous membranes, splenomegaly,

lymphadenomegaly, and hydropericardium. Microscopically, numerous

large schizonts are present within the cytoplasm of endothelial-associated

macrophages. Infected macrophages become markedly enlarged (up

to 75 micrometers) and may occlude the lumens of numerous vessels

of many tissues, especially the lungs. Minimal inflammatory reaction

is present in tissues.

-

- Each schizont may contain numerous merozoites. Ultrastructurally,

schizonts lack a parasitophorous vacuole, and individual merozoites

possess rhoptries. Merozoites within erythrocytes, best seen

on peripheral blood or tissue impressions, are variable in morphology

and can occur as round, oval, or signet ring-shaped bodies 1-5

micrometers in diameter with a small, peripherally placed basophilic

nucleus.

-

- Organisms that must be distinguished from the intraerythrocytic

phase of C. felis include Babesia and Hemobartonella, because

the blood stage may appear similar to the ring forms of Hemobartonella

and to the piriforms of Babesia. Unlike Cytauxzoon, however,

babesiosis and hemobartonellosis do not have a tissue stage of

infection. Differential diagnosis for the tissue phase of cytauxzoonosis

includes other small (less than 5 m), intrahistiocytic organisms

such as Toxoplasma, Leishmania, and Histoplasma.

-

- References:

- 1. Cowell RL, Panciera RJ, Fox JC, Tyler RD: Feline cytauxzoonosis.

Compend Cont Ed Pract Vet 10:731-735, 1988.

- 2. Garner MM, Lung NP, Citino S, Greiner EC, Harvey JW, Homer

BL: Fatal cytauxzoonosis in a captive-reared white tiger (Panthera

tigris). Vet Pathol 33:82-86, 1996.

- 3. Kier AB, Greene CE: Cytauxzoonosis. In: Infectious Diseases

of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 470-473, WB Saunders Co., 1998.

- 4. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Diseases due to protozoa.

In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed., pp. 599-600, Williams and

Wilkins, 1997.

- Contributor: PAL-PATH, Inc., 1277 Record Crossing Road, Dallas,

TX 75235.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #'s 5298-5300, 5829-5831, 7986, 14300, 9642.

-

Case IV - 97-26234 (AFIP 2642418 [corrected])

-

- Signalment: Four-year-old, female, spayed, Pug, canine.

-

- History: The dog was originally presented for peripheral

lymphadenopathy which was diagnosed via excisional lymph node

biopsy as granulomatous lymphadenitis secondary to mycobacteriosis.

Lymph node culture revealed Mycobacterium avium. The dog did

well for two years on a multiantibiotic treatment regimen. Regularly

scheduled appointments to monitor the disease included serum

chemistries and palpation of peripheral lymph nodes which initially

regressed in size. Two years after diagnosis, the lymph nodes

began to enlarge again, and since the dog was shedding M. avium

in the feces as confirmed by culture, she was euthanized at that

time.

- Gross Pathology: The spleen was greatly enlarged (2800

g; 30x6x4 cm). It was meaty in texture and was mottled cream-colored

to yellow throughout the parenchyma. The mesenteric and cecocolic

lymph nodes were enlarged and uniformly cream-colored to tan

on cut section.

-

- Laboratory Results: Blood chemistries: Hypoalbuminemia,

hypocholesterolemia, decreased BUN.

-

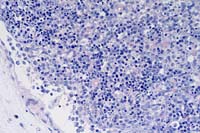

- Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Disseminated

granulomatous disease, mycobacteriosis, Mycobacterium avium.

-

- Although gross changes were confined to the spleen and intestinal

lymph nodes, there were multifocal infiltrates of macrophages

in the lungs, liver, kidneys, thyroid gland, bone marrow, intestines,

and other lymph nodes. Acid-fast stains of sections revealed

numerous acid-fast bacteria in macrophages in all tissues examined.

Splenic architecture was effaced by sheets of macrophages with

binucleate and multinucleate forms and epithelioid macrophages

with a few foci of residual lymphoid cells. The bone marrow was

almost completely effaced by macrophages, although some myeloid

and erythroid cells remained. Perivascular infiltrates of macrophages

were present throughout the lungs and liver and in the lamina

propria of multiple intestinal sections.

-

- Mycobacteriosis in dogs is uncommon in the U.S. since the

effort to eradicate tuberculosis in domestic animals has been

largely successful. The dog is experimentally equally susceptible

to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. bovis, but is considered

resistant to M. avium. Infection is generally via inhalation

of aerosols or ingestion of infected material. The size of the

inoculum, the number of times an animal is exposed to the organism,

and the immune status of the individual all determine whether

an active mycobacterial infection becomes established.

-

- While a route of exposure to M. avium was not determined

for this dog, a possibility that remains is that the dog frequently

visited a location that was adjacent to a major waterfowl staging

area. The dog had a habit of being a "garbage hound"

and would always ingest things it found on the ground or floor.

If this dog was ingesting M. avium-infected waterfowl droppings

or inhaling infected aerosols repeatedly, the cumulative exposure

to M. avium could have been great enough for infection to occur.

There was no indication given in the record regarding the immune

status of this dog.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

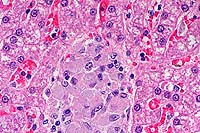

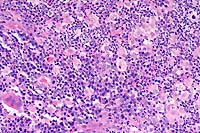

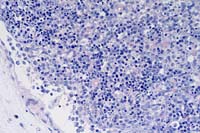

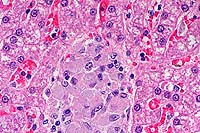

- Case 3-4. Liver. Demonstrates focus of epithelioid

macrophages replacing normal hepatic cords. These cells are filled

with ill defined rod shaped structures.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

- Case 3-4. Lung. Similar clusters of epithelioid macrophages

and lymphocytes expand alveolar septa near moderate sized blood

vessels. Macrophages contain granular to rod shaped material.

40x

obj. Zeil-Neilson

40x

obj. Zeil-Neilson

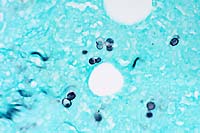

- Case 3-4. Lung. Cell clusters adjacent to vessels

like those described above contain myriad acid fast bacilli.

-

- AFIP Diagnosis:

- 1. Liver: Hepatitis, granulomatous, portal, central, and

multifocal, moderate, with numerous intrahistiocytic bacilli.

- 2. Lung: Pneumonia, granulomatous, perivascular, multifocal,

moderate, with numerous intrahistiocytic bacilli.

- 3. Lung: Congestion, diffuse, moderate, with abundant alveolar

edema.

-

- Conference Note: Mycobacterial infections in man and

animals are caused by bacteria belonging to the family Mycobacteriaceae,

order Actinomycetales. Mycobacterium is a genus compromising

morphologically similar, aerobic, gram- positive, non-spore forming,

and non-motile bacilli with wide variations in host affinity.

They have the unique property of being acid-fast due to the high

lipid content of mycolic acid in the cell wall.

-

- The bacteria have been subdivided into several groups and

individual species based on biochemical and culture characteristics.

The species causing "classic" tuberculosis are termed

the M. tuberculosis complex (MTC) and include M. bovis, M. tuberculosis,

M. africanum (rare cause of human TB in Africa), and M. microti

(a rodent pathogen that has been reported to infect cats). Those

species grouped together causing the syndrome of M. avium complex

(MAC), sometimes referred to as "avian mycobacteriosis",

include Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare and M. avium susp.

paratuberculosis. The latter, which is the cause of Johne's disease

in ruminants (ruminant paratuberculosis), can infect monogastric

animals and produces lesions in stump-tailed macaques that are

very similar to Crohn's disease in man, thus implicating this

bacteria as a potential etiology for the human disease. Another

separate group of myocobacterial infections is caused by M. leprae

and called either leprosy or Hansen's disease, while feline and

murine leprosy is caused by M. lepraemurium. The final group,

termed "atypical mycobacteriosis", can be described

as the localized opportunistic skin and subcutaneous infections

caused by saprophytic and rapidly growing mycobacteria, e.g.

M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, etc.

-

- Classic tuberculosis in immunocompetent humans results in

the formation lumps or nodules called tubercles (from the Latin

word "tuberculum"), and histologically consists of

well-formed granulomas composed of epithelioid macrophages, Langhans-type

multinucleate macrophages, and lymphocytes. Acid-fast mycobacteria

are few and difficult to find. Granuloma formation, which fundamentally

requires sufficient numbers of functioning macrophages and T

helper-1 lymphocytes, is often absent in humans and nonhuman

primates that are immunocompromised due to concurrent infection

with immunodeficiency viruses.

-

- Instead, these individuals and animals develop disseminated

disease with diffuse granulomatous inflammatory infiltrates and

contain more abundant acid-fast organisms.

- In dogs and cats, MAC infections are uncommon; in humans

MAC organisms are of low virulence in immunocompetent individuals,

but cause infections in 15 to 24% of patients with HIV infections

that become severely immunocompromised (less than 60 CD4+ cells

per cubic mm). Most infections in all three species are caused

by M. avium-intracellulare, often originate in the gastrointestinal

tract via oral ingestion, and become widely disseminated to the

liver, spleen, lung, and lymph nodes. Spread to skin, bone, cervical

vertebrae, mammary gland, and serous surfaces may also occur

in animals.

-

- Histologically, MAC infections in most mammals, including

humans, are characterized by a diffuse granulomatous, inflammatory

reaction containing large numbers of epithelioid macrophages

without necrosis, fibrosis, or calcification. Macrophages are

packed with high numbers of acid-fast bacilli, which may appear

as "negative images" in hematoxylin and eosin stained

sections. Langhans-type multinucleated macrophages may be present,

but not always. There is little lymphocytic response. In dogs

and cats, lesions are multifocal and coalescing to diffuse, and

the inflammatory cells often displace or replace affected tissues

creating a "sarcomatous" appearance.

-

- The histological similarities of MAC infections in cats and

dogs to immunocompromised humans infected with MAC suggest that

innate immunodeficiency may predispose these small animals to

the disease. Histologically, the character of the inflammation

in immunodeficient humans concurrently infected with classic

tuberculosis more closely resembles MAC infections in dogs and

cats than the character of classic tuberculosis in immunocompetent

individuals, further supporting the theory of a deficiency in

cell-mediated immunity in these animals. Finally, there is evidence

that a genetic predisposition to MAC infections may exist in

basset hounds, miniature schnauzers, and Siamese cats.

-

- References:

- 1. Feldman WH: The pathogenicity for dogs of bacilli of avian

tuberculosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 76:399-419, 1930.

- 2. Francis J: Tuberculosis in small animals. Mod Vet Pract

39-42, 1961.

- 3. Snider WR: Tuberculosis in canine and feline populations.

Am Rev Resp Dis 104:877-887, 1971.

- 4. Liu S: Canine tuberculosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 177:164-167,

1980.

- 5. Thoen C O, Himes E M: Mycobacterium. In: Pathogenesis

of Bacterial Infections in Animals, pp. 26-37, Iowa State University

Press, 1986.

- 6. Carpenter J L, et al.: Tuberculosis in five Bassett Hounds.

J Am Vet Med Assoc 192:1563-1568, 1988.

- 7. Shackelford CC, Reed WM: Disseminated Mycobacterium avium

infection in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest 1:273-275, 1989.

- 8. Clercs C, et al.: Tuberculosis in dogs: A case report

and review of the literature. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 28:207-211,

1992.

- 9. Eggers JS, et al.: Disseminated Mycobacterium avium infection

in three miniature schnauzer litter mates. J Vet Diagn Invest

9:424-427, 1997.

-

- Contributor: University of Minnesota, Veterinary Diagnostic

Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, 1333 Gortner Avenue,

St. Paul, MN 55108.

-

- International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #'s 21897, 9127, 9926.

-

- Ed Stevens, DVM

Captain, United States Army

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: STEVENSE@afip.osd.mil

-

- * The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

-

Return to WSC Case Menu

20x

obj.

20x

obj.  GMS

40x obj.

GMS

40x obj.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.  GMS

40x obj.

GMS

40x obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

10x

obj.

10x

obj.

20x

obj.

20x

obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj.

40x

obj. Zeil-Neilson

40x

obj. Zeil-Neilson