Results

AFIP Wednesday Slide Conference - No. 30

27 May 1998

Conference Moderator:

LTC Thomas P. Lipscomb, Diplomate, ACVP

Division of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

Washington, D.C. 20306

Return to WSC Case Menu.

Case I - S-51-96 (AFIP 2593311)

Signalment: Free-ranging, male, pink river dolphin (Inia

geoffrensis).

History: This animal was captured in the course of a

radio-tagging field study conducted in Lago Mamiraua, Brazil.

Gross Pathology: A heavily vascularized, multinodular,

pedunculated mass was attached to the right eye. It was firmly

adhered to, and appeared to arise from, the conjunctiva of the

dorsal palpebrum as well as the medial and lateral canthus.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Conjunctiva: Conjunctivitis,

proliferative, chronic-active to granulomatous, diffuse, marked,

with mucosal hyperplasia and intralesional fungal elements compatible

with Rhinosporidium seeberi.

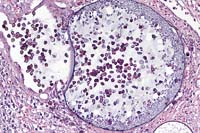

The polyploid conjunctival lesions seen in this dolphin are "classic"

examples of an infection with Rhinosporidium seeberi. Although

a number of different blocks were used for glass slide recuts,

all slides demonstrate the developmental stages of R. seeberi.

These are readily identified by specific histologic features.

These are:

- 1. Trophocyte (juvenile sporangia)

- - averages 10-100 microns

- has a 2-3 micron unicellular wall

- each has a central nucleus with prominent nucleolus

- granular to flocculent cytoplasm

- no mature endospores

-

- 2. Intermediate sporangia

- - are larger than trophocytes

- these lack a nucleus

- have thicker, bilamellar walls

-

- 3. Mature sporangia

- - hallmark of R. seeberi infection

- average 100-300 microns diameter

- "zonation" of mature and immature endospores

- mature endospores have "eosinophilic globular bodies"

Little is known about the epidemiology of this organism. Although

generally considered to be a fungus, its taxonomy is still uncertain

and it has yet to be cultivated on synthetic media. R. seeberi

typically induces the formation of chronic inflammatory nasal

polyps. Conjunctival lesions have been reported, but these are

far less common than respiratory lesions.

- This organism has been studied most intensively in man, although

animal cases have been documented and described in horses, mules,

cattle, dogs, a goose, 2 ducks and, most recently, in 41 swans

from a lake in central Florida. This outbreak lends support to

the hypothesis that R. seeberi may be an aquatic organism.

-

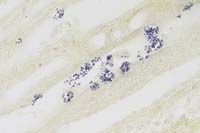

Case 30-1. Skin. A mature sporangium of Rhinospordium

seeberi is discharging some of its endospores to surface of the

skin. A small portion of an immature sporangium is at the edge.

It contains only floccular eosinophilic material. 20X

AFIP Diagnosis: Stratified squamous epithelium and loose

connective tissue: Inflammatory polyp, with moderate chronic-active

inflammation, multifocal hemorrhage, epithelial necrosis, and

multiple fungal sporangia, pink river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis),

cetacean, etiology consistent with Rhinosporidium seeberi.

Conference Note: Based only on the morphology of the

infecting organism, the differential diagnosis might include coccidioidomycosis

and adiasporomycosis. However, the spherules of Coccidioides immitis

are generally smaller than rhinosporidial sporangia, and they

contain endospores that are generally the same size and shape

throughout the spherule. Chrysosporium parvum, the etiologic agent

of adiasporomycosis, is larger than Rhinosporodium, has a thicker

wall, and does not reproduce by endosporulation.

Rhinosporidiosis occurs sporadically worldwide, but is hyperendemic

in India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia.1,2 Infection is associated

epidemiologically with rural and aquatic environments. A recent

study from India suggests that Rhinosporidium seeberi is a form

of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa, which was isolated

from water samples in which human patients with rhinosporidiosis

were bathing.8

Contributor: Wildlife Conservation Society, Department

of Pathology, 185th St. and Southern Blvd., Bronx, NY 10460

- References:

- 1. Chandler FW, Kaplan W, Ajello L: Color Atlas and Text

of the Histopathology of Mycotic Diseases. Year Book Medical

Publishers, Inc. Chicago. pp. 109-111, 1980.

- 2. Chandler FW, Watts JC: Pathologic Diagnosis of Fungal

Infections. ASCP Press, Chicago. pp. 27-33, 1987.

- 3. Cheville NF: Ultrastructural Pathology. An Introduction

to Interpretation. Iowa State University Press. Ames, IA. pp.

775-776, 1994.

- 4. Gaines JJ, Clay JR, Chandler FW, Powell ME, Sheffield

PA, Keller III AP: Rhinosporidiosis: three domestic cases. Southern

Medical Journal 89(1):65-67, 1996.

- 5. Kennedy FA, Buggage RR, Ajello L: Rhinosporidiosis: A

description of an unprecedented outbreak in captive swans (Cygnus

spp.) and a proposal for revision of the ontogenic nomenclature

of Rhinosporidium seeberi. Journal of Medical and Veterinary

Mycology 33:157-165, 1995.

- 6. Kwon-Chung KJ: Phylogenetic spectrum of fungi that are

pathogenic to humans. Clinical Infectious Diseases 19 (Suppl

1): S1-7, 1994.

- 7. Levy MG, Meuten DJ, Breitschwerdt EB: Cultivation of Rhinosporidium

seeberi in vitro: interaction with epithelial cells. Science

234:474-476, 1986.

- 8. Ahluwalia KB, Maheshwari N, Deka RC: Rhinosporidiosis:

a study that resolves etiologic controversies. Am J Rhino 11(6):479-483,

1997.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #6637, 6638, 6639, 8246, 4471, 14472, 14473

Case II - 94-114 (AFIP 2453724)

Signalment: 8-week-old, female, New Zealand White, rabbit.

History: Incidental finding in a rabbit infected with

Campylobacter jejuni.

Gross Pathology: None.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Kidney: Nephritis,

interstitial, chronic, moderate, with gram positive intraepithelial

protozoal organisms - Etiology consistent with Encephalitozoon

cuniculi.

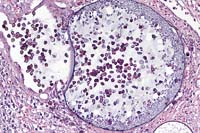

Encephalitozoon cuniculi is an occasional, usually asymptomatic,

parasite of rabbits. The primary importance of the organism in

rabbits is interference with the interpretation of experimental

data. In other species (dogs, cats, and wild carnivores) the organism

causes clinical, often fatal encephalitis and nephritis.

The organisms are most commonly found in the renal tubular

epithelial cells and capillary endothelial cells within the central

nervous system.

- Differentiating Encephalitozoon cuniculi from toxoplasmosis

can be accomplished a number of ways. Encephalitozoon stains

poorly on H&E, is gram positive, and its spores are birefringent;

Toxoplasma stains well on H&E, stains poorly with Gram stains,

and is not birefringent.

-

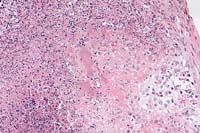

- Case 30-2a. Kidney. Tubule whose lumen is filled with

necrotic epithelial cells that contain numerous but vague eosinophilic

organisms in the cytoplasm. 40X

-

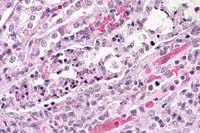

- Case 30-2b. Kidney. Numerous microsporidian organisms

(Encephalitozoon cuniculi) in a degenerating tubule. Gram. 40X

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephritis, tubulointerstitial,

acute to chronic, multifocal, moderate, with tubular dilatation,

tubular epithelial necrosis, and intracellular and extracellular

protozoa, New Zealand white rabbit, lagomorph.

Conference Note: Transmission of Encephalitozoon cuniculi,

a microsporidian, is primarily via ingestion of urine containing

the infective spores. Transplacental infection has also been reported.3

In addition to the susceptible species listed above, infection

occurs in rats, mice, guinea pigs, hamsters, and humans.3 At least

three strains of E. cuniculi have been identified based on host

specificity and other criteria.4

Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection of mice is used as a model

of human microsporidiosis. Mouse strains differ greatly in their

susceptibility to infection, with C57BL/6, DBA/1, and 129J being

highly susceptible, and BABL/c, A/J, and SJL strains being relatively

resistant.4 Athymic (nu/nu) mice experience high mortality with

infection.

Contributor: Naval Medical Research Institute, Pathobiology

Division, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889-5607

- References:

- 1. Szabo JR, Shadduck JA: Experimental encephalitozoonosis

in neonatal dogs. Vet Pathol 24:99-108, 1987.

- 2. Cutlip RC, Beall CW: Encephalitozoonosis in arctic lemmings.

Lab Anim Sci 39(4):331-333, 1989.

- 3. Soulsby EJL: Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of Domesticated

Animals, 7th edition, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 742-743,

1982.

- 4. Baker DG: Natural pathogens of laboratory mice, rats,

and rabbits and their effects on research. Clinical Microbiology

Reviews 11(2):231-266, 1998.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #5278-5281, 19463.

Case III - Mississippi State University (AFIP 2376327)

Signalment: Adult, female, cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus

floridanus)

History: This animal was found alive but weak, depressed,

thin, and easily captured.

Gross Pathology: The animal was emaciated, flea infested,

and had several ticks. The peritoneal cavity contained approximately

10 ml of serous fluid. The spleen was 2x2x6 cm, and multiple disseminated

pinpoint to 1 mm white foci were visible on the capsular and cut

surfaces. The liver had similar foci. Mesenteric, hilar and mediastinal

lymph nodes were enlarged, gray, and friable. Several tapeworm

cysts were noted in the peritoneal cavity and attached to the

liver and pleura.

Laboratory Results: Francisella tularensis was isolated.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Disseminated multifocal

and coalescing necrotizing splenitis.

- This case represents a classic case of tularemia. Care should

be taken by prosectors as this condition is zoonotic.

-

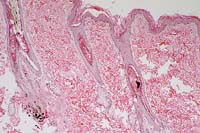

- Case 30-3. Spleen. There is extensive liquefactive

necrosis of paranchyma with vague, basophilic, intralesional

bacterial colonies (center). 20X

- AFIP Diagnosis: Spleen: Splenitis, necrotizing, acute

to subacute, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with necrotizing

vasculitis, fibrin thrombi, and numerous colonies of coccobacilli,

cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus), lagomorph.

Conference Note: Gram stains demonstrated that the coccobacilli

are gram-negative.

Tularemia (deer fly fever, rabbit fever) is a zoonotic disease

with worldwide distribution, affecting more than 100 species of

wild and domestic mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles. It is primarily

a disease of wild rabbits and rodents and -shares many key features

with endemic plague, with which it was originally confused in

a 1911 outbreak in ground squirrels in Tulare County, California.

There are two antigenically similar strains of F. tularensis:

1. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (Type A) occurs only in

North America, where it is the most frequently isolated strain

(70% of human cases). It is associated with tick borne tularemia

in rabbits, and produces the classic disease in humans.

2. F. tularensis subsp. palaearctica (Type B) occurs throughout

the world (except Australia and Antarctica), and is less virulent

than Type A. It is associated with mosquitoes and rodents, and

is frequently linked to waterborne disease of rodents, particularly

beavers and muskrats.

Transmission of the disease may occur by a variety of routes

including direct contact of the organism with intact or abraded

skin or mucous membranes, ingestion or inhalation of the organism,

or by percutaneous inoculation via arthropod vectors. As few as

10 bacilli may induce disease when inhaled or injected, whereas

a much larger dose is required for oral infection.

Ticks are reported most frequently as the source of human infection

in the United States, followed by rabbits. Two seasonal peaks

are associated with tularemia: one during tick season, the other

during the hunting season, associated with contact with infected

rabbits. Dermacentor variabilis (dog tick), D. andersoni (wood

tick), and Amblyomma americanum (lone star tick) are considered

the most important tick vectors in North America. Both transstadial

and transovarian passage of F. tularensis have been documented,

making the tick both a vector and a reservoir of infection. The

deerfly, Chrysops discalis, is also an important vector in North

America.

Clinical signs are those of an acute septicemia and vary with

the route of infection, the strain of the organism, and the species

involved. Rabbits and rodents are often found dead without premonitory

signs. In cats, tularemia is associated with nonspecific clinical

signs, including pyrexia, anorexia, lethargy, lymphadenopathy,

oral ulcers, hepatomegaly, and icterus.2

Contributor: Mississippi State University, College of

Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State, MS 39762

- References:

- 1. Davidson WR, Nettles VF: Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases

in the Southeastern United States. Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife

Disease Study, pp 212-215, 1988.

- 2. Woods JP, Crystal MA, Morton RJ, Panciera RJ: Tularemia

in two cats. JAVMA 212(1):81-83, 1998.

- 3. Valli VEO: The hematopoietic system. In: Pathology of

Domestic Animals, 4th edition, Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N

(eds.), Academic Press, Inc, vol. 3, pp. 244-245, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #3476, 3477, 5307, 5308, 11121-11124, 22253.

Case IV - 90-4468 (AFIP 2327342)

Signalment: 2-year-old, male, Doberman Pinscher, canine,

named "Mr. Blue".

History: This dog had a history of chronic keratoconjunctivitis

and generalized bilaterally symmetrical hair loss.

Gross Pathology: Bilaterally symmetrical hair loss.

Laboratory Results: Antinuclear antibody: 1:20

Baseline T4: 0.2 (normal 1.0-4.0)

Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments:

Haired skin: Diffuse superficial and follicular orthokeratotic

hyperkeratosis

Multifocal follicular atrophy with melanin clumping

Multifocal, perifollicular melanophage accumulation

Mild superficial perivascular hyperplastic dermatitis

Condition: Color mutant alopecia.

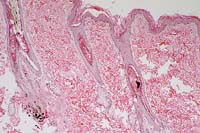

- These sections demonstrate the classic histologic features

of color mutant alopecia in the dog: diffuse superficial and

follicular orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis; dilated keratin-filled

follicles; multiple melanin aggregates within hair shafts and

bulbs; occasional fractured hairs; diffuse, moderate adnexal

atrophy; and scattered, generally perifollicular, deep dermal

and pannicular aggregates of melanophages. In this case, there

is a minimal superficial perivascular dermatitis with mild epidermal

hyperplasia. Most sections have one or more anagen hair follicles,

though many follicles are atrophied. Some sections contain intrafollicular

accumulations of inflammatory cells. Arrector pili muscles are

present, but not enlarged or vacuolated. The low baseline T4

level might indicate, but is not diagnostic for, hypothyroidism.

There are no histologic changes to suggest hypothyroidism and

it is unknown if the dog was on thyroid medication at the time

of biopsy. Besides the blue Doberman, this condition can be seen

in fawn Irish Setters, red and fawn Dobermans, and other "blue"

varieties of various breeds.

-

- Case 30-4. Skin. There is hair follicle atrophy with

clumping of melanin in one follicle accompanied by mild intrafollicular

hyperkeratosis. 4X

- AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin: Follicular atrophy, ectasia,

and hyperkeratosis, diffuse, moderate, with intrafollicular melanin

clumping, peribulbar melanophages, and mild multifocal superficial

lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic dermatitis, Doberman Pinscher,

canine.

Conference Note: This hereditary syndrome is associated

with a color-dilution gene, but it is not known if the gene is

directly responsible for initiating the skin disease or if a linked

gene codes for the associated follicular changes.2

Clinically, this disease is characterized by a gradual onset

of a dry, dull, brittle, poor-quality hair coat. Hair shafts break,

and regrowth is often poor. Follicular papules and comedones may

develop, and chronic cases may exhibit hyperpigmentation.

The clinical differential diagnosis of color mutant alopecia

should include other generalized atrophic or dysplastic diseases

affecting the hair follicle including hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism,

canine follicular dysplasia, and acquired pattern alopecia.2

Contributor: Department of Pathology, Cornell University,

Ithaca, NY 14853

- References:

- 1. Brignac MM, Foil CS, Al-Bagdadi FAK, Kreeger J: Microscopy

of color mutant alopecia. Ann Meet Am Acad Vet Dermatol and Am

Coll Vet Dermatol., pp. 14-15, 1988.

- 2. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ: Veterinary Dermatopathology.

A macroscopic and microscopic evaluation of canine and feline

skin disease. Mosby Year Book, St. Louis, MO, pp. 298-301, 1992.

- 3. Scott DW, Miller Jr WH, Griffin CE: Muller & Kirk's

Small Animal Dermatology, 5th edition, W.B. Saunders Company,

Philadelphia, pp. 777-779, 1995.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #11787, 11856, 11857, 13848-13851.

Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American

College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry

of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides

substantial support for the Registry.

Return to WSC Case Menu.