Signalment: Adult, male, radiated tortoise (Geochelone radiata).

History: This tortoise was housed on St. Catherine's Island, Georgia, USA. It had a 2 week history of lethargy, anorexia and a mild oral discharge. Blood was drawn for a complete blood count and serum biochemical profile. Symptoms did not improve with antibiotics and supportive care. The animal was found dead in the enclosure.

Laboratory Results:

|

Test |

|

|

| Hematology: | ||

| Total solids |

|

|

| WBC x 103 |

|

|

| hematocrit (%) |

|

|

| WBC Differential%: | ||

| Mono | 12 | 4 |

| Lymph | 48 | 37 |

| Seg | 25 | 47 |

| Eos | 0 | 4 |

| Baso | 15 | 8 |

| Serum Chem: | ||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 6.3 | 10.8-14.4 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 78 | 46-93 |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 2.4 | 0-0.6 |

| Total Protein (g/dL) | 4.2 | 3.2-5.0 |

| AST (IU/dL) | 495 | -- |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.2 | -- |

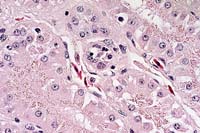

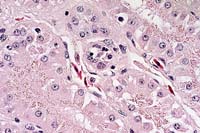

Histopathology: Section of kidney. Scattered throughout the section, multifocal renal tubules are in various stages of degeneration. Individual renal tubular epithelial cells have granular to vacuolated, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. Small numbers of renal tubular epithelial cells also exhibit nuclear pyknosis. The central lumen of occasional tubules contains moderate amounts of an amorphous, eosinophilic material. Numerous renal tubular epithelial cell nuclei contain single to multiple, round to elliptical, eosinophilic to amphophilic, often membrane bound, intranuclear inclusions ranging up to 8 mm in diameter. Occasional infected nuclei are up to 2 times normal size with marginated chromatin. Often the surrounding interstitium is infiltrated by minimal to moderate numbers of inflammatory cells. In some sections little inflammation is present. The infiltrate is composed of moderate numbers of mature lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells and scattered eosinophils. The cytoplasm of few renal tubular epithelial cells contains round, granular brown pigment (lipofuscin) or round, eosinophilic granules (protein droplets) predominantly located along the apical border.

In some, but not all, sections an adjacent fragment of adrenal gland is present. Occasional adrenal cell nuclei contain the previously described intranuclear inclusions and associated inflammation.

Electron microscopy: Ultrastructural evaluation of the intranuclear inclusion bodies in the renal tubular epithelial cells demonstrated various stages of developing coccidia.

Over 30 coccidian species have been identified in turtles and tortoises. Most of these are rarely associated with lesions and typically undergo endozoic development within the cytoplasm. There are, however, at least 11 species of Eimeria, Isospora, and Cyclospora known to have stages with intranuclear development. Four of these have been identified in reptiles, specifically in lizards. This animal originated from the same group reported in the article by Jacobson et al.1 At this time, little is known about the origin and life cycle of this coccidian. The transmission cycle and definitive host are also unknown. Jacobson et al1 considered the North American skink as a possible definitive host because intranuclear coccidiosis has been described in this species. However, this was later ruled out due to ultrastructural differences. The severity of infection in the tortoises suggests these non-indigenous animals may be serving as aberrant hosts for this parasite.

Conference Note: A few sections viewed in conference also contained a small section of urinary bladder which contained similar protozoal organisms.

Scattered renal epithelial cells contain numerous small eosinophilic droplets. Eosinophilic droplets in renal tubular epithelial cells are commonly seen in normal male rats. In male snakes, they are seen in the tubular portion of the nephron known as the sex segment.3 It is unclear whether the presence of these droplets in chelonians is a sex-related phenomenon, but they are considered non-pathologic.

The four species of intranuclear coccidia reported to infect reptiles are all members of the genus Isospora, and all have been reported in lizards, one of which is a North American skink (Scincella lateralis).1

Contributor: Wildlife Conservation Society, Department of Pathology, 185th St. and Southern Blvd, Bronx, NY 10460

Signalment: 16.5-year-old, castrated male, Domestic Shorthair cat.

History: This cat had a history of chronic liver disease and had been on Prednisone, which had been tapered and discontinued after it was felt that it had no benefit. Two weeks later, he developed acute episodes of dyspnea with crying, flaccidity, tachycardia, etc. An echocardiogram revealed a pericardial mass with effusion. He was euthanized, and his body was received in a frozen condition for necropsy the following day.

Gross Pathology: Animal was in good nutritional condition

with moderate amounts of abdominal and subcutaneous fat. There

was 80 ml of straw-colored fluid in the abdominal cavity. The

lungs were uniformly dark red. There was 12 ml of clear red fluid

in the pleural cavity. There was a multilobular, firm, white to

tan, 2x2x4 cm mass involving the pericardial sac and base of the

mainstem bronchi. The gastrointestinal tract contained small amounts

of normal ingesta. The colon contained formed feces. The liver

was mottled and had an irregular surface with multiple dark red

nodules up to 2 cm in diameter. There were multiple 2-3 mm shrunken

white areas on the surface of the liver that were cystic on cross

section. The liver was firm on cross-section. The left thyroid

lobe was enlarged and measured 2x0.75 cm. The right thyroid lobe

measured 1x0.5 cm.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Pericardium: Osteosarcoma,

Domestic Shorthair, feline.

Conference Note: The mass is composed of spindled and polygonal cells arranged in bundles, streams and whorls. Multifocally, neoplastic cells are separated or surrounded by a homogeneous eosinophilic matrix consistent with osteoid. Invasive growth, extensive necrosis, frequent mitoses and nuclear atypia indicate malignancy. By immunohistochemistry, many of the neoplastic cells are positive for S-100 protein. The essential feature of osteosarcoma, production of osteoid by malignant cells, is present. In humans and dogs, osteosarcomatous differentiation occurs rarely in malignant melanoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Thus, these neoplasms were considered in the differential diagnosis. Melanomas and nerve sheath tumors are often S-100 positive; S-100 positivity has also been reported in human osteosarcoma. We are unaware of any reports of osteosarcomatous differentiation in feline melanomas or nerve sheath tumors. No histologic features highly characteristic of melanoma (such as brown to black cytoplasmic pigment) or nerve tumor (such as Verocay bodies) were observed in the examined sections. Thus, the evidence supports the contributor's diagnosis of osteosarcoma. Whole body radiographic examination is helpful in excluding the possibility of an undetected primary osteosarcoma in bone when extraskeletal osteosarcoma is suspected.

Osteosarcomas are the most common skeletal neoplasms in both cats and dogs.2 They most commonly arise in the metaphyseal region of long bones. Some arise in the periosteum. In dogs, osteosarcomas of the axial skeleton metastasize less readily than those of the appendicular skeleton8, while the opposite is true in cats.2 Primary extraskeletal osteosarcomas are rare in animals other than dogs where it is usually associated with mammary neoplasia.

In a study of 106 osteogenic tumors of dogs, alterations in the expression of p53 tumor suppressor protein correlated with highly aggressive tumor behavior.8 Canine appendicular osteosarcomas had a significantly higher prevalence of p53 overexpression than did osteosarcomas of the axial skeleton and multilobular tumors of bone. However, it is unclear whether p53 overexpression can be used as a prognostic factor in patients with osteosarcoma.

Contributor: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C. 20307-5100.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #14639, 20877, 20878

Signalment: 7-year-old, Persian, neutered male, cat.

History: Progressive darkening of the iris unilaterally for several months.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Feline diffuse iris melanoma arising from iridal melanosis.

Conference Note: Conference participants noted a paucity of mitotic figures in this neoplasm when compared to other feline iridal melanomas previously examined at the AFIP. This finding may be due to the early stage of the neoplastic transformation.

The biological behavior of most primary ocular melanocytic neoplasms in the cat differs from that in the dog. In cats, Patnaik found that 62.5% of intraocular melanomas metastasized, with mandibular and submandibular lymph nodes the most common metastatic location.2 In contrast, 75 of 91 (82%) canine primary ocular melanomas were benign.3

Melanin is formed in melanocytes when the enzyme tyrosinase catalyzes the oxidation of tyrosine to dihydroxyphenylalanine. The expression of the tyrosinase gene is specific for melanocytes and melanotic tumor cells, and in situ hybridization for mRNA encoding for tyrosinase has been used to verify the melanocytic origin of amelanotic melanomas in cats.4

Contributor: School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin, 2015 Linden Drive West, Madison, WI 53706

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #9460, 16857, 16858

Signalment: 6-month-old, female, Holstein, bovine.

History: This was one of 40 affected animals out of a herd of 82. All affected animals were acutely dyspneic and febrile.

Gross Pathology: There were dozens of foci of parenchymal collapse. The foci were primarily in the cranioventral lung fields, and were red-brown and rubbery to firm.

Laboratory Results: Virology testing was positive for bovine respiratory syncytial virus.

Etiology: Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV).

The clinical history and gross and histologic features are characteristic of the natural disease. Multifocally throughout the section, there is a marked bronchial and bronchiolar infiltrate of many neutrophils which frequently fill the lumina and infiltrate the lining epithelium. There are a few scattered admixed sloughed epithelial cells as well as syncytial epithelial cells along the bronchiolar mucosa. Occasional syncytial epithelial cells have small numbers of indistinct round to oval (~5 mm) eosinophilic viral inclusion bodies within the cytoplasm. There is moderate multifocal bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia and scattered mild epithelial hydropic degeneration. The inflammatory infiltrate extends out into the surrounding alveolar spaces and there is mild multifocal type II pneumocyte hyperplasia.

Conference Note: Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) usually affects young cattle, 6-8 months of age, and occasionally adult cattle. Although BRSV infection in adult cattle has usually been described as asymptomatic or as having mild clinical signs, some outbreaks with severe clinical signs have been described in adult dairy cattle. Most BRSV infections occur in the fall and early winter. Herd outbreaks are characteristic, and case fatality rates may range from 1-30%. BRSV may be the sole agent involved in a respiratory disease outbreak, but co-infections with other agents as part of the enzootic pneumonia or shipping fever complexes are common. The incubation period is 5-7 days and the disease may be acute, mild, or inapparent. Most animals recover within 2 weeks of infection.

Lesions are thought to be due to a direct viral cytopathic effect on bronchial, bronchiolar, and alveolar epithelium. In the early stages of the disease, an exudative and necrotizing bronchiolitis, with bronchiololar epithelial syncytia formation, results in obstructive atelectasis of associated lung parenchyma. A subsequent accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages in bronchioles and alveoli may be the consequence of the presence of viral antigens, of necrosis, or of secondary bacterial infection.

BRSV is antigenically related to human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), an important respiratory pathogen in children and immunocompromised patients. Other pneumoviruses of veterinary importance include mouse pneumovirus and turkey rhinotracheitis virus.

Contributor: Cornell University, Department of Pathology, New York State College of Veterinary Medicine, Ithaca, NY 14853-6401

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #15599-15602, 22842, 22853-22845.

Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.