Signalment: Adult, female, Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus).

History: This animal was involved in a pathogenesis study of Burkholderia (formerly Pseudomonas) mallei (glanders). Six days post-intraperitoneal injection with a lethal dose of organisms, the animal was found moribund and was euthanized with CO2.

Gross Pathology: Among hamsters examined in this study, the most striking pathologic change at necropsy was splenomegaly with variably-sized, white/cream- colored foci of necrosis and inflammatory cell infiltrate. In the late stages of the disease (days 5 and 6), discrete white foci (inflammatory cell infiltrates) were present in the lungs as well. Extensive adhesions of abdominal viscera were related to intraperitoneal injection. The nasal and oropharyngeal cavities were not studied at necropsy because the skull was fixed intact for decalcification and sectioning.

Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments: 1. Nasal cavity:

Rhinitis, myelitis, periostitis, myositis, fasciitis, pyogranulomatous,

necrotizing, multifocal and coalescing, marked. 2. Oropharyngeal

cavity: Periodontitis, pyogranulomatous, necrotizing, multifocal,

marked; pulpitis, pyogranulomatous, necrotizing, focal, mild to

moderate.

Etiology: Burkholderia mallei.

Glanders is a serious infection of equine animals (and occasionally others such as goats, sheep, cats and dogs) caused by Burkholderia (formerly Pseudomonas) mallei. A number of instances of airborne infection have been reported in laboratory workers. Glanders was at one time widespread throughout Europe, but its incidence has steadily decreased in most countries following introduction of control measures. The disease still occurs in Asia, Africa, and South America, but not in Western Europe or North America. There have been no naturally acquired infections in the U.S. or Canada since 1938.

Burkholderia mallei is a gram-negative aerobic bacillus. It is closely related to B. pseudomallei, the agent of melioidosis. Unlike B. pseudomallei, however, B. mallei is non-motile and is an obligate animal parasite. The route of infection, the dose and virulence of inoculated organisms are the determining factors in the severity of the disease, which consists of two basic manifestations: the nasal-pulmonary form (glanders) and the cutaneous form (farcy), which may be present simultaneously and are usually accompanied by systemic disease. Clinical disease may be acute or chronic, or the disease may be subclinical and even latent. The chronic form is more typically seen in horses and most likely results from an oral route of infection. In the mule and donkey, however, acute disease is the usual form; the route of infection here is probably by nasal and/or tracheal inoculation. Interestingly, there is currently no evidence for immunity by virtue of previous infection or vaccination. In horses with clinically resolved glanders, the disease recrudesced when animals were re-challenged with B. mallei. Antibiotic therapy is unreliable.

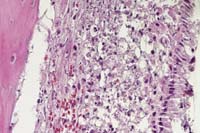

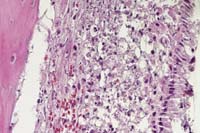

The typical early histologic lesion of glanders in the susceptible host (i.e. hamster, guinea pig) is pyogranulomatous inflammation, later organizing into discrete pyogranulomas with a necrotic center and persistent, leukocytic, karyorrhectic debris. Distribution of pyogranulomas is miliary throughout lungs and other tissues. Because of their uniform susceptibility to infection, the Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) has become the traditional animal model in glanders studies. In the more resistant host (i.e. mice; also horses), the inflammatory process tends to become well walled-off, have central mineralization, and in some cases, abundant peripheral multinucleated giant cells. We have not found giant cells in any hamster lesions, regardless of glanders strain given. We have not seen giant cells in any of the few mice examined to date, even those which had survived infection for 45 days. Clearly, in natural infections of many animal species, giant cells are present.

Persistence of pyknotic/karyorrhectic debris centrally within pyogranulomas is said to be a feature of glanders infection and a distinguishing feature between glanders and miliary tuberculosis. The histologic distinction between the two was more important early in this century. In the older literature, this feature is termed "chromatotexis" and "chromatotaxis". It is, however, characteristic of but not pathognomic for glanders and was always present in hamster lesions.

The submitted 2x2 slide of a transmission electron (TEM) micrograph was taken at an original magnification of 6,600X of a pulmonary pyogranuloma in a hamster killed on day 6 post-inoculation. Within an alveolus (no septal structures visible) there are necrotic cells (presumably leukocytes) with fragments of (karyorrhexis) pyknotic nuclei, cell debris, and fibrin. Four glanders bacilli are present and all appear to be intracellular and surrounded by a lucent halo of uniform thickness. We believe that the halo was occupied by the organism's capsule, lost during routine TEM processing. Some references state that B. mallei is not encapsulated, but several recent Russian papers show evidence of a capsule in some phases of infection. Also note that within these organisms are round lucent foci with a central dense granule. We believe these may be b-hydroxybutyrate granules which have been described in these bacilli.

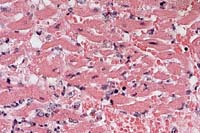

By light microscopy, this organism is said to stain very poorly with most stains. The glanders bacillus is difficult to distinguish by hematoxylin and eosin staining unless it is present in significant numbers, which it almost never is. Likewise, differential stains, such as Lillie-Twort, were not helpful. Even light microscopy (LM)-level immunostaining was of limited value: abundant bacterial antigen but few bacilli. TEM study of multiple tissues revealed that the best site to find/study bacilli was on the periphery of pulmonary pyogranulomas; organisms in other tissues were exceedingly difficult to find. By LM, we had the most success with the Giemsa stain; this stains the bacilli (and unfortunately most other structures) very strongly. Illustrating this problem is the submitted 2x2 light micrograph (60X) of the periphery of a pulmonary pyogranuloma at day 6. Several free bacilli are visible; there are also a number of intracellular (leukocytes) bacilli which are resolvable only with difficulty.

Conference Note: In most sections viewed in conference, the nasolacrimal duct was partially or completely occluded by mucinous material with few inflammatory cells and sloughed epithelium. Degeneration of neurons in the vomeronasal organ is believed to be secondary to inflammation and necrosis of the more rostral portion of the nerve cell processes.

Transmission of glanders in horses requires close contact. The introduction of the automobile, which led to a marked decrease in the population density of horses stabled in metropolitan areas, is believed to be an important factor in the overall decreased incidence of glanders in the twentieth century. Horses serve as the reservoir host of B. mallei, and man and carnivores are accidental hosts.4 In human glanders, the mortality rate approaches 90%.3

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #4540-4542, 18886-18889

Signalment: 2.5-month-old, female, Arabian horse.

History: Four week history of respiratory disease, non-responsive to a variety of antibiotics. Nasal discharge, uveitis OU, crackles and wheezes over entire chest, fetlocks distended. Disoriented and anorexic.

Gross Pathology: Lungs diffusely firm with multiple

nodules ranging from 0.5 cm to 5 cm in diameter scattered throughout

all lung lobes. Nodules encapsulated by firm white connective

tissue and contain green/yellow purulent to caseous material (abscess).

Thymus small to imaginary; small lymph nodes. Pharyngeal and esophageal

Candida sp., bilateral hyphema, unilateral hypopyon.

Laboratory Results: Lymphopenia - 0 lymphocytes; mature

neutrophilia - 25,200/ml; IgM undetectable; IgG - 235 mg/dl (decreased);

fibrinogen - 1000 mg/dl; lung - heavy growth of Rhodococcus equi.

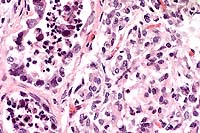

The lesions, signalment and clinical pathology results (absence of lymphocytes on CBC and undetectable IgM levels) are diagnostic for severe combined immunodeficiency (CID). Granulomas/abscesses ranging from 0.5 to 5 cm in diameter were scattered throughout all lung lobes.

Tissue from the cranial mediastinum was examined histologically, and identified as thymus by the presence of Hassall's corpuscles and epithelial cells. Lymphoid tissue was markedly reduced throughout lymph nodes and spleen with no recognizable follicles. Plaques of Candida sp. in yeast and hyphal forms infiltrated by large numbers of neutrophils are present on laryngeal and esophageal mucosa.

Conference Note: Gram stains performed at the AFIP revealed moderate numbers of intrahistiocytic gram positive coccobacilli within pulmonary granulomas.

Combined immunodeficiency (CID), also known as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), is the most important congenital equine immunodeficiency. The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait in Arabian horses. There has been one report of CID in an Appaloosa foal1, but pedigree analysis found at least one Arabian stallion in its ancestry, leaving open the possibility of genetic transmission. Foals affected with CID fail to produce functional T or B lymphocytes. After colostrum-derived antibodies wane in these foals, they become agammaglobulinemic, and usually die by 4 to 6 months of age as a result of overwhelming infections. Common etiologic agents include equine adenovirus, Rhodococcus equi, Pneumocystis carinii and Cryptosporidium parvum.

The specific defect in CID lies in a DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) which is an essential enzyme in gene segment rearrangement during the synthesis of B- and T-cell receptors (BCR and TCR). During this process, large segments of DNA are excised so that V (variable), D (diversity), and J (joining) gene segments can be joined together. The DNA-PK, which rejoins the cut ends, consists of 3 linked peptides called KU80, KU70, and p350. In CID foals, the p350 component is totally absent. As a result, neither T nor B cells can form functional V regions in their TCR or BCR, so they are unable to respond to any antigen.5

Diagnosis of CID in foals requires that at least two of the

following criteria be established:

1) circulating lymphocytes £ 1000/mm3

2) hypoplasia of primary and secondary lymphoid organs

3) absence of IgM from presuckle serum (the normal equine fetus

synthesizes IgM, so a normal foal will always have some IgM in

its serum.)5

Contributor: North Carolina State University, College of Veterinary Medicine, 4700 Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, NC 27606

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #2432, 2433, 2497-2499, 2619, 1620, 2715, 2716,

3120, 3121, 3908-3910, 4926, 4932, 4933, 5681, 5891-5893, 6657,

6658, 6717-6719, 7646, 8019, 9436, 12717, 12718, 12806-12808,

14424, 14425, 20945, 20946, 20977, 20978, 22224, 23351, 23352.

Signalment: 14-month-old, female, Holstein-Friesian, bovine.

History: This heifer was one of a group of 54 animals on pasture and the second one to die within a two week period. It was found in sternal recumbency, reluctant to rise. When forced to move, it promptly lay down in a nearby pool of water. By the time it died four hours later, it had experienced severe dyspnea. Necropsy was completed within two hours of death.

Gross Pathology: The carcass was fresh, in very good nutritional condition and mildly dehydrated. There was a slight deposition of fibrin on the pleural surface of the lungs in contact with the pericardial sac. Approximately 30% of the pulmonary parenchyma in a cranioventral distribution was congested and edematous. There was a diffuse thin layer of fibrin on the epicardium, with scattered patches of black discoloration of the underlying myocardium. Numerous fibrinous plaques, each approximately 0.5 to 1 cm diameter, were present on the endocardial surfaces of the right and left atria and ventricles including the atrioventricular valves, and on the intimal surfaces of the pulmonary artery and aorta. The superficial and deep pectoral muscles had large locally-extensive dry, emphysematous, reddish-black friable areas with a rancid odor. The diaphragm was thickened by multiple foci of gelatinous edema fluid and hemorrhage.

Laboratory Results: Stained impression smears of heart, pericardial fluid and skeletal muscle had 2+, 2+, and 1+ Gram positive rods, respectively. Fluorescent antibody tests of heart and skeletal muscle were positive for Clostridium chauvoei, negative for Cl. novyi and Cl. septicum. Culture results of lung, spleen and liver were negative. Small numbers of Cl. chauvoei were isolated from heart, pericardial swab and skeletal muscle.

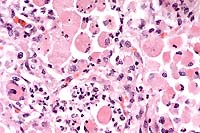

Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments: Heart (papillary muscle, left ventricle): Myocarditis, necrotizing, acute, transmural, severe with intralesional spore-forming rod-shaped bacteria; epicarditis, fibrinonecrotizing, acute, moderate, diffuse; endocardial necrosis, severe, acute, diffuse. Etiology: Clostridium chauvoei. Myocardium: intracellular protozoal cysts.

Conference Note: Clostridial myositis (synonyms: blackleg, black quarter, emphysematous gangrene) caused by Clostridium chauvoei occurs most frequently in cattle from 9 months to 2 years of age. The infection is acquired by the ingestion of spores during grazing. The pathogenesis differs from that of clostridial wound infections, in that ingested spores multiply in the intestine and pass through the intestinal mucosal barrier (possibly via macrophages) into blood and lymphatic circulation. The spores disseminate to tissues, especially muscle and liver, where they may lie dormant for long periods. These spores are activated by local events that create increased pH and lower oxygen tension. Clostridium chauvoei organisms have been found in the liver and spleen of up to 20% of normal cattle, suggesting that the liver may serve as a source for dissemination to muscle.

Clostridial exotoxins are elaborated and produce necrosis locally. The toxins produced include alpha toxin (hemolytic, necrotizing, and leukocidal activity), hyaluronidase (spreading activity), and deoxyribonuclease. There is toxin-induced myonecrosis, and injury to the capillary endothelium with resulting hemorrhage and edema, enhanced by the spreading effects of alpha toxin and hyaluronidase and the production of gas bubbles during the replication phase. Circulating toxins and tissue breakdown products lead to fatal toxemia.

Affected animals are frequently found dead without any observed clinical signs. Typical initial signs include lameness, depression, anorexia, rumen stasis, and high fever. Examination may reveal foci of subcutaneous crepitation over major muscles of the thigh, rump, loin, or shoulder that are initially small and hot but that rapidly enlarge and become cold and painless. Clinical signs progress rapidly and include tremors, dyspnea, and death in 12 to 24 hours.

Contributor: Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, 52 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5B4

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #2810, 3316, 3317, 3420, 3421, 3704, 4176, 5041,

5250, 6476, 13550, 18957, 24296.

Signalment: 8-month-old, male, Springer Spaniel, canine.

History: This dog had a six week history of progressive bilateral hindlimb ataxia which was worse on the right side. On physical examination, the dog exhibited severe upper motor neuron paresis of the hindlimbs with normal cranial nerve and forelimb responses. No conscious proprioceptive deficits, spinal pain or upper motor neuron signs to the bladder were observed. The dog was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: Alimentary and abdominal cavity: Several feathers were found in the stomach. All other body systems had no visible lesions.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Nonsuppurative necrotizing encephalomyelitis (severe) due to Neospora caninum.

Conference Note: Neospora caninum is an obligate intracellular apicomplexan parasite. Natural infection has been reported in several mammalian species, including dogs, cats, sheep, cattle, goats, and horses. Definitive hosts and sexual stages are presently unknown, but a carnivorous host is suspected due to the organism's structural similarity to Toxoplasma gondii.10 Tachyzoites and tissue cysts containing bradyzoites are the only known stages of N. caninum. Tachyzoites have been found in many cell types, whereas tissue cysts have only been found in neural tissues.2

Neospora caninum causes fatal disease in dogs of all ages, although it is most commonly reported in young dogs, where it is usually characterized by severe progressive ascending paralysis, polyradiculoneuritis, polymyositis, and encephalomyelitis. In cattle, N. caninum is recognized as a cause of abortion and neonatal loss. A recent study showed that N. caninum can readily infect sheep and be pathogenic for the ovine fetus, with resulting lesions that resemble those induced by T. gondii in pregnant ewes.11

Distinguishing N. caninum from T. gondii by light microscopy can be difficult. Neospora caninum tissue cysts, which occur only in neural tissue, have a 1-4 mm thick wall, whereas T.gondii cysts may be found in many tissues and the cyst wall is always less than 1 mm thick.6 The use of other diagnostic techniques such as electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescent antibody tests are preferred in making a definitive diagnosis.

Contributor: University of Minnesota, Department of Veterinary Diagnostic Medicine, 1333 Gortner Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55108

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #22918-22920.

Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.