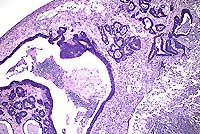

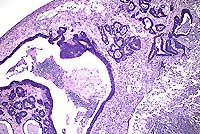

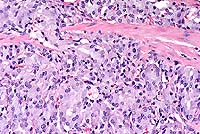

AFIP Diagnosis: Colon: Adenocarcinoma, colonic, Long-Evans rat, rodent.

Signalment: 26- to 30-month-old, male, Long-Evans, rat.

History: The rat was euthanized with a history of weight loss occurring over several weeks. This rat had not been used on any study.

Gross Pathology: A tan mass filled the lumen of a 1 cm segment of colon. Adjacent to this area, the serosal and mesenteric fat contained several coalescing, firm, cream-colored to gray nodules up to 1 cm in diameter.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Adenocarcinoma, colon, rat.

Conference Note: There was considerable variation in the slides distributed for this case. Several slides viewed in conference demonstrated minimal or no invasion of neoplastic cells into the tunica muscularis, and no neoplastic cells were present in the subserosal abscess. This led some participants to a diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma in situ. However, in other slides, invasive growth indicative of malignancy is evident.

In nonhuman primates, primary intestinal adenocarcinomas are relatively rare, with the exception of the cotton-top tamarin, in which colonic adenocarcinomas are often coincident with chronic proliferative colitis. In dogs, rectal adenocarcinomas causing stenosis sometimes follow the development of rectal polyps. There is a higher incidence in older male dogs, with breed predilection for Boxers, Collies, Poodles and German Shepherd Dogs. In cats, the ileum is the most common site of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas, and there is a higher incidence in older males and Siamese cats. In sheep, adenocarcinoma of the ileum and/or jejunum is relatively common in New Zealand, Britain, Iceland, Scotland, Norway, and southeastern Australia.4 In contrast, intestinal carcinomas are rare in cattle, goats, horses, and swine.4

Contributor: Abbott Laboratories, D-469 AP13A, 100 Abbott Park Road, Abbott Park, IL 60064-3500.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #1965, 2546, 2547, 3816, 10932, 23971

Signalment: 11-year-old, spayed female, Cocker Spaniel, canine.

History: This 13-kg Cocker Spaniel presented to the referring veterinarian for nodules on the ventrum and rear limbs. The owner first noticed the nodules 1 week prior to presentation and became concerned since they were increasing in number and size. One nodule had an opening to the surface of the skin that drained a purulent exudate; a large parasite was expressed from the nodule. The dog was otherwise alert, active, and afebrile. Hematology and biochemical profiles were within normal limits and fecal flotation was negative. The dog was routinely treated monthly with oral ivermectin heartworm preventative. The dog lived in southwestern Wisconsin, but vacationed regularly in central Wisconsin near a spring-fed lake. The dog swam in that lake and periodically ate snails.

Gross Pathology: Subcutaneous nodules measuring 2-3

cm in diameter were palpable in the skin. The surrounding skin

was erythematous. Nodules developed an opening that drained a

purulent exudate. The largest nodules were surgically removed.

The dog continued to develop additional nodules and, to date,

75 adult parasites identified as Dracunculus insignis have been

removed.

Histopathology: A histologic section of a representative

nodule reveals pyogranulomatous nodules localized in the deep

dermis containing multiple cross sections of parasitic nematodes

and numerous embryos, both in a large uterus and free in the exudate.

The adults have a thick cuticle and a prominent coelomyarian musculature.

In some sections, there is a small focus of epidermal ulceration

with pyogranulomatous inflammation intermingled with embryos at

the skin surface.

Conference Note: This case was reviewed by C.H. Gardiner,

PhD, veterinary parasitology consultant to the AFIP. He pointed

out additional characteristics of the parasite which are evident

in histologic section, including:

a. Prominent coelomyarian muscles found in two "bands"

that are separated by large, low lateral chords.

b. Small intestine, identifiable by the presence of iron pigment

in the epithelial cells.

c. Distinctive larvae that are prominently cross-striated and

have very long tails containing phasmids (identified as "reddish

circles" at the base of the tail).

Phasmids are chemoreceptors located in the caudal extremity, posterior to the anus. The presence or absence of phasmids has been the basis of the classification of nematodes into the Phasmidia or Aphasmidia. This system of classification is no longer in use.2

Dracunculus insignis has an indirect life cycle. The first stage larvae are discharged by the adult female upon contact of the skin lesion with water. The larvae are ingested by a copepod (Cyclops sp.), then develop into third-stage (infective) larvae. Frogs (Rana pipiens and R. clamitrans) have been shown experimentally to be suitable paratenic hosts.2 Dogs are infected by ingesting infected copepods or infected frogs. Upon ingestion by a suitable host, the larvae migrate and develop into adults in the subcutis of the definitive host. The adults may be found in the extremities as early as 120 days postinfection. The prepatent period is 309-410 days. In addition to the subcutis, the parasite can also be found in the conjunctiva, heart, vertebral column, and scrotum.2

A similar species, Dracunculus medinensis, also known as the

"guinea worm", infects humans in India, Pakistan, West

and Northeast Africa, and the Middle East. It is also seen in

dogs, and occasionally in horses and cattle.2

The life cycle is similar to that of D. insignis.

Contributor: School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin, 2015 Linden Drive West, Madison, WI 53706

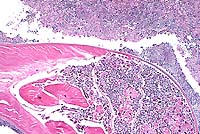

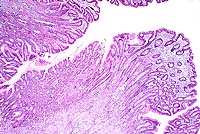

Signalment: 8-year-old, female, baboon (Papio cynocephalus)

History: This animal had a history of weight loss and loose feces. It was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The animal was emaciated. There was excessive clear fluid in the peritoneal and pericardial cavities. The small and large intestines were atonic and contained yellow fluid digesta. The glandular stomach was markedly irregularly thickened (approximately 10x normal; see gross photo.)

Laboratory Results: Low total protein; low sodium; culture of stomach and colon: unremarkable.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Hyperplastic foveolar gastropathy (Menetrier's disease); etiology undetermined.

Five baboon stomachs (out of 215 examined) with marked mucosal thickening and giant hypertrophic folds and nodules were found incidentally at necropsy. These baboons were thin and had chronic diarrhea. The condition was not diagnosed clinically. The increased mucosal thickening was due to hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium. Two of the stomachs were classified as Menetrier's disease (MD) and three as varioliform lymphocytic gastritis (VLG). These cases were histologically identical with those gastropathies in humans and may represent a useful model of disease in the future. According to Wolfsen et al, and Cheli, human hypertrophic gastropathies should be classified into a) MD - mucosal hyperplasia with little or no inflammation, b) VLG - multiple nodular hyperplasia with or without intraepithelial lymphocytosis and as c) HLG - diffuse hypertrophic lymphocytic gastritis.

This case was classified as MD because of the diffusely increased mucosal thickness due primarily to foveolar hyperplasia. The section also has numerous glandular cysts, limited inflammation and a normal number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (<16/100 epithelial cells).

The causes of MD and VLG in humans are unclear. They have been associated with allergies, gastric or duodenal ulcers, hiatal hernias, cirrhosis or cholelithiasis and with Helicobacter pylori. Some authors have questioned Helicobacter pylori as an etiologic agent.

Conference Note: The Division of Gastrointestinal Pathology of the AFIP also reviewed this case and agreed that the giant folds are consistent with Menetrier's disease (MD).

In humans, MD is a gastric giant folds disease syndrome, but all parts of the syndrome may not be present at the same time. The full syndrome includes giant folds, gastric protein loss, and decreased gastric acid production, accompanied by a histologic complex that includes foveolar hyperplasia and distortion, glandular atrophy, and edema but little inflammation, in the lamina propria.5 The gastric pits (foveolae) are unusually elongated, and frequently extend from the surface to the base of the mucosa. They occasionally penetrate the muscularis mucosa, ending as cysts surrounded by smooth muscle. The superficial lamina propria is usually edematous, and may contain low numbers of plasma cells and eosinophils.

The cause of MD is unknown; however, it is now being linked to excessive levels of growth factors, particularly transforming growth factor alpha (TGFa). A histologically and clinically identical condition has been produced in transgenic mice that overexpressed TGFa in their stomachs.5

Contributor: Armstrong Lab AL/OEVP, 2509 Kennedy Circle, Brooks AFB, San Antonio, TX 78235

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #1535, 3405, 3406, 7846

Signalment: Adult, female Sprague-Dawley rat.

History: This rat was sacrificed at the termination of a carcinogenicity study on day 738.

Gross Pathology: The glandular stomach was thickened. Additional gross findings were those commonly seen in aged rats and included tissue masses of the pituitary and liver, mottled adrenals, unilateral ovarian cysts, and unilateral renal distention.

Conference Note: Conference participants viewed a photograph provided by the contributor which demonstrated positive immunohistochemical staining for neuron-specific enolase in the neoplastic cells. In addition, by immuno-histochemistry performed at the AFIP, the neoplastic cells were positive for synaptophysin. The Churukian-Schenk method demonstrated numerous argyrophilic cytoplasmic granules.

Little is known about the biological activity of gastric neuroendocrine tumors in rats and mice. Metastasis to local lymph nodes has seldom been reported.2 Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are rare in laboratory animals, with the exception of the African rodent Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis, in which gastric carcinoid tumors were reported in two-thirds of males and one-third of females in a closed colony of 600 animals.3,4 In that colony, metastasis was noted in 25% of the cases.3

Contributor: Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 556 Morris Ave., Summit, NJ 07901

Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.