Signalment: 5-year-old, intact female, Brittany Spaniel Canine.

History: This dog had a 6-week history of chronic diarrhea. The diarrhea was fluid and contained some blood. The dog was non-responsive to treatment and progressively became severely emaciated, hypoproteinemic, hypoalbuminemic and developed a non-regenerative anemia. The dog was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: There was a marked, generalized reduction

in muscle mass and fat stores with serous atrophy of fat. There

was extensive generalized subcutaneous edema and ascites. Hepatomegaly

was marked and the liver was pale, friable and bulged over the

capsular surface when cut. Distributed along the entire length

of the gastrointestinal tract, there were multifocal to coalescing

white nodular transmural firm thickenings (1-5 cm) which had a

smooth serosal surface and multifocal ulcerations of the mucosa.

Similar nodular lesions were present in the adrenal glands (bilateral)

involving both the cortex and medulla and throughout the spleen.

There was generalized enlargement of lymph nodes (5 - 10 X normal)

which were multinodular, mottled white tan and firm. The lungs

were wet, heavy (pulmonary edema) and there were non-discrete,

irregular areas of lung, multifocally involving all lobes which

were pale and firm. They ranged in size from 0.5 cm to

4 cm in diameter.

Laboratory Results: Total Protein - 3.5 g/dl; Albumin - 1 g/dl; PCV - 21%; Fecal Floatation - Negative. Adrenal function was not evaluated clinically.

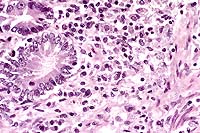

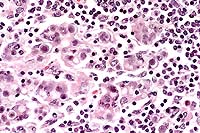

Contributor's Diagnoses and Comments:

The wide spread dissemination of the H. capsulatum organism throughout the body resulted in these additional lesions:

3. Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing granulomatous

hepatitis with intralesional yeasts (Histoplasma capsulatum).

4. Severe, chronic, diffuse granulomatous lymphadenitis with intralesional

yeasts (Histoplasma capsulatum).

5. Moderate, chronic, multifocal granulomatous pneumonia with

intralesional yeasts (Histoplasma capsulatum).

6. Severe, chronic, multifocal to coalescing granulomatous splenitis

with intralesional yeasts (Histoplasma capsulatum).

Conference Note: Disseminated histoplasmosis causes a variety of clinicopathologic findings. In dogs, hematologic abnormalities often include a leukocytosis resulting from neutrophilia and monocytosis. There may be a left shift. As was seen in this case, a nonregenerative anemia is common, due both to chronic inflammatory disease and to replacement of normal bone marrow elements by Histoplasma-laden histiocytes. Thrombocytopenia has been a variable feature in dogs.

Serum chemistry changes indicating cholestatic liver disease are often found, including increases in serum alkaline phosphatase activity and conjugated bilirubin levels. Serum albumin is often decreased. Alanine aminotransferase is only occasionally increased, due to the infiltrative rather than hepatocellular nature of the disease. Serum globulin concentrations may be normal or increased.

In cats, clinicopathologic changes are reported to be similar to those in dogs, and can include nonregenerative anemia, degenerative left shift, neutropenia, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperglobulinemia.

Contributor: University of Illinois, Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, 2001 South Lincoln Avenue, Urbana, IL 61802

References:

1. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N: (eds) Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th Edition, Volume 3, Academic Press, pp. 247-249, 334, 1993.

2. Yager JA, Wilcock BP: Color Atlas and Text of Surgical Pathology of the Dog and Cat: Dermatopathology and Skin Tumors, Mosby-Year Book Europe, pp. 128, 130-131, 1994.

3. Kowalewich N, Hawkins EC, Skowronek AJ, Clemo FA: Identification of Histoplasma capsulatum organisms in the pleural and peritoneal effusions of a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993; 202(3):423-426.

4. VanSteenhouse JL, DeNovo RC Jr: Atypical Histoplasma capsulatum infection in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986; 188(5):527-528.

5. Kabli S, Koschmann JR, Robertstad GW, Lawrence J, Ajello L, Redetzke K: Endemic canine and feline histoplasmosis in El Paso, Texas. J Med Vet Mycol 1986; 24(1):41-50.

6. Mitchell M, Stark DR: Disseminated canine histoplasmosis: a clinical survey of 24 cases in Texas. Can Vet J 1980; 21(3):95-100.

7. Barsanti JA. Histoplasmosis. In: Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of The Dog and Cat, Greene CE, ed., Saunders, pp.687-698, 1984.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #367, 12892.

Signalment: 4-month-old, Berkshire, female, porcine.

History: Over a 2-to-3 week period approximately 28, 2- to 3-week-old piglets from the same pen died. A couple of pigs in the pen were coughing. This pig was sick for approximately 10 days and had a rough hair coat. The pig was given penicillin for a couple of days but did not improve.

Gross Pathology: This 8.6 kg, female Berkshire pig has fibrin and a congealed coagulum of red-tinged fluid on the pleural surface of the lungs and ribs, and fibrin on the serosal surface of the abdominal organs. The anteroventral aspect of the left and right cranial lung lobes are purple and firm, involving approximately 30% of both sides. There is fibrin adhered to 80% of the dorsal pleural surface of the lungs, with the greatest amount adhered to the anterior aspect. In the lumen of the trachea, extending down the bronchi, are numerous, thin, white, 2-6 cm long, nematode parasites consistent with Metastrongylus spp. There is a layer of fibrin adhered to the epicardial surface of the heart. There are greater than 50 ascarid parasites in the lumen of the distal esophagus, stomach, and small intestines. There are multiple, variably-sized white foci disseminated randomly on the serosal surface of the liver and throughout the parenchyma. There is a single ascarid parasite in the lumen of the bile duct extending into the gall bladder. All lymph nodes are prominent.

Laboratory Results:

a. Microbiology - A heavy growth of Escherichia coliwas isolated from samples of lung, lymph node, and brain. Samples of brain and lymph node were negative for Mycoplasma spp. after 14 days incubation and negative for Hemophilus spp. A sensitivity was performed on the E. coli isolate.

b. Parasitology - A fecal sample was positive for coccidia (Eimeria spp.) and Ascaris suum.

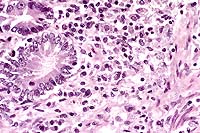

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: 1. Severe, subacute to chronic, lobular, eosinophilic, interstitial pneumonia and bronchiolitis with intrabronchiolar nematode parasites and intra-alveolar eggs containing larvae, lung. 2. Severe, subacute, fibrinous pleuritis, lung.

Metastrongylus is the only genus found in the family Metastrongylidae. All species are large white parasites of the bronchi and bronchioles of swine and the three most important species of this genus are M. apri, M. pudendotectus, and M. salmi. The intermediate host for these parasites is the earthworm. The oviparous females lay eggs containing the first stage larvae which are then passed in the feces of infected swine. The eggs do not hatch or develop into infective larvae unless they are ingested by an earthworm. In the earthworm, the larvae develop to the third, infective stage in approximately 10 days and remain quiescent unless the earthworm is eaten by a pig. Migration in the pig is through the lymphatics from the intestine to the lungs. In this case, the interstitial pneumonia and bronchiolitis in this pig may be the result of both the Metastrongylus parasites, as well as migration of Ascaris suum larvae due to the heavy ascarid load.

Nematode parasites found in the lungs of other mammalian species include:Dictyocaulus filaris (sheep, goats, other small ruminants), D. viviparous (cattle) and D. arnfieldi (horses, donkeys), Protostrongylus rufescens (sheep, goats, deer), Muellerius capillaris (sheep, goats), Crenosoma vulpis (foxes), Filaroides hirthi(dogs), Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (cats), and Angiostrongylus vasorum (dogs, foxes).

Conference Note: Acute inflammation resulting from bacterial infection has three major components. These include alterations in vascular caliber leading to increased blood flow, structural changes in the microvasculature which permit leakage of plasma proteins and leukocytes, and emigration of leukocytes from the microcirculation and their accumulation in the extravascular tissue.

The fibrinosuppurative pleuritis seen in this case is the result of increased vascular permeability. At least five mechanisms of vascular leakage are known, not all of which occur with all types of injury. The most common mechanism is endothelial cell contraction, an immediate transient response elicited by histamine, bradykinin, leukotrienes, and other chemical inflammatory mediators. This response is usually reversible and short-lived (minutes).

A second reversible mechanism is endothelial cell retraction, which can be induced in vitro by IL-1, TNF- , and IFN- . This response is delayed 4-6 hours after injury, and lasts 24 hours or more. It is not clear how frequently this mechanism accounts for vascular leakage in vivo.

Direct endothelial injury is often encountered in necrotizing injuries due to direct damage to endothelial cells by injurious agents such as severe burns or lytic bacterial infections. Usually, vascular leakage attributed to this mechanism begins immediately and is sustained for several hours until the damaged vessels are thrombosed or repaired. Leukocyte-mediated endothelial injury, by release of toxic oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, and leakage from regenerating capillaries, also play roles in increasing vascular permeability and leakage.

Contributor: University of Connecticut, Department of Pathobiology, 61 North Eagleville Road, U-89, Storrs, CT 06269-3089.

References:

1. Barker IK. The Peritoneum and Retroperitoneum. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds, Academic Press, New York, NY, vol. 2, p. 436, 1993.

2. Dungworth DL. The Respiratory System. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds., Academic Press, New York, NY, vol. 2, p. 677-688, 1993.

3. Reams RY, Glickman LT, Harrington DD, Thacker HL, Bowersock TL. Streptococcus suis infection in swine: a retrospective study of 256 cases. Part II. Clinical signs, gross and microscopic lesions, and coexisting microorganisms. J Vet Diagn Invest, 6:326-334, 1994.

4. Vahle JL, Haynes JS, Andrews JJ. Experimental reproduction of Hemophilus parasuis infection in swine: clinical, bacteriological, and morphologic findings. J Vet Diagn Invest, 7:476-480, 1995.

5. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL. Robbins Pathologic Basis

of Disease, 5th ed., WB Saunders Co., pp. 54-56, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #1883, 15619

Signalment: Adult female bovine.

History: Presented for slaughter at USDA inspection facility in Idaho. Normal antemortem.

Gross Pathology: Green foci in cortices of mediastinal lymph nodes.

Laboratory Results: None.

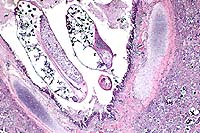

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Mediastinal lymph node: Chronic multifocal granulomatous lymphadenitis with intralesional green algal forms.

Morphologic description: There are multifocal infiltration, expansion, and replacement of normal lymph node structure by aggregates of epithelioid macrophages, multinucleate giant cells, and plasma cells. The two former cells often contain numerous cytoplasmic algal forms characterized by: single ovoid structures (8-12 microns) with granular basophilic central material and a dense eosinophilic cell wall, similar structures without central basophilic material and with cleavage (endosporulation into 4-8 ellipsoid forms) within the cell wall. The organisms contain numerous coarse anisotropic and periodic acid-Schiff positive granules (starch granules). Impression smears of fixed lymph node reveal green oval organisms on unstained smears, and similar organisms on H&E- and Giemsa- stained smears are green in color. There were numerous coarse anisotropic granules in the organisms on smears.

Conference Note: GMS and PAS stains performed at the AFIP revealed numerous cytoplasmic granules in the organisms. Also, the granules remained PAS-positive after diastase treatment. This finding differs from a previous report by Chandler et al1, who stated that these granules were PAS-negative following diastase digestion. They also noted that similar granules are present in Protothecacells, but in much lower numbers, and the granules are smaller and less distinct. Ultrastructurally, Chlorella cells contain chloroplasts, consisting of irregularly shaped cytoplasmic granules surrounded by membranes stacked in alternating bands of two to five lamellae. True chloroplasts have not been found in Prototheca. In the absence of gross pathologic findings and special staining techniques, it remains difficult or impossible to differentiate green algae and Prototheca cells in tissue stained by H&E.

Prototheca spp., thought by some to be achloric mutants of the genus Chlorella, include two species known to be pathogenic in animals and man, P. zopfiiand P. wickerhamii. These organisms are found in soil, water, tree sap, potato skin, sewage, and feces of pigs and humans. Prototheca generally causes progressive granulomatous lesions in numerous animal species. Lesions include cutaneous infections in cats and humans, mastitis in cows, and disseminated infections in dogs. The intestine and the eye are the most commonly involved sites in canine protothecosis.

In dogs, chronic, intractable, bloody diarrhea and passage of blood-stained feces are frequent presenting signs, along with progressive weight loss. A prominent lesion is hemorrhagic and ulcerative colitis.

Contributor: USDA FSIS OPHS Pathology, Russell Research Center, College Station Road, P.O. Box 6085, Athens, GA 30604

References:

1. Chandler FW, Kaplan W, Callaway CS. Differentiation between Prototheca and morphologically similar green algae in tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 102:353-356, 1978.

2. Connole MD. Review of animal mycoses in Australia. Mycopathologica 111:133-164, 1990.

3. Cordy DR. Chlorellosis in a lamb. Vet Pathol 10:171-176, 1973.

4. Costa EO, Ribeiro AR, Melville PA, Prada MS, Carciofi AC,

Watanabe ET. Bovine mastitis due to algae of the genus Prototheca.

Mycopathologica

133:85-88, 1996.

5. Zakia AM, Osheik AA, Halima MO. Ovine chlorellosis in the Sudan. Vet Record 125:625-626, 1989.

6. Barker IK, Van Dreumel AA, Palmer N. The Alimentary System.

In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed. Academic Press, Inc.,

Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds. Vol. 2. p. 258, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #: none

History: A juvenile, female control dog on a one month toxicity study.

Gross Pathology: None

Laboratory Results: N/A

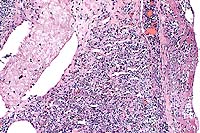

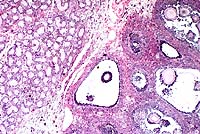

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Ovotestis.

Chromosomal sex is normally determined at fertilization by the formation of either an XY or XX zygote. The Tdy gene on the Y chromosome encodes the protein testis-determining factor, which initiates testicular differentiation. Studies in mice have shown Tdy to be the only Y-linked gene necessary for testicular differentiation. Male phenotypic sexual determination results from the testicular secretion of 1) Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS), which causes the Müllerian duct system to regress, and 2) testosterone, which promotes development of the vas deferens and epididymides from the Wolffian ducts. In the absence of the Y chromosome and Tdy gene, the default pathway to female gonadal sexual differentiation is initiated.

Hermaphrodites are classified according to the morphology of

the gonads present. A true hermaphrodite has at least one gonad

containing ovarian and testicular tissue (i.e. an ovotestis) or

has one male and one female gonad. A pseudohermaphrodite has gonads

of one sex and accessory reproductive organs of the opposite sex.

A male pseudohermaphrodite has testes and female accessory sex

organs; a female pseudohermaphrodite has ovaries and male accessory

reproductive organs.

Contributor: Wyeth-Ayerst Research, 641 Ridge Road, Chazy,

NY 12921

References:

1. Meyers - Wallen VN. Genetics of sexual differentiation and anomalies in dogs and cats. J. Reprod. Fert., Supp. 47: 441-452, 1993.

2. McEntee K. Intersexes. In: Reproductive Pathology of Domestic

Mammals,Academic Press, pp. 8-22, 1990.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #2230, 16687.

Terrell W. Blanchard

Major, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: blanchard@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.