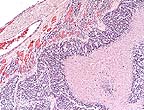

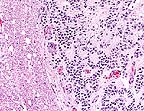

High-grade astrocytoma in

the cerebrum of a rhesus monkey showing characteristic palisading

of neoplastic cells along areas of necrosis. (HE, 40X, 54K)

High-grade astrocytoma in

the cerebrum of a rhesus monkey showing characteristic palisading

of neoplastic cells along areas of necrosis. (HE, 40X, 54K)Signalment: Adult male Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta).

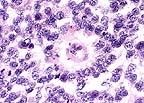

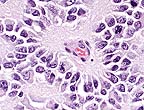

True rosette formation in

a high-grade astrocytoma in a Rhesus macaque. (HE, 400X, 81K)

True rosette formation in

a high-grade astrocytoma in a Rhesus macaque. (HE, 400X, 81K)

History: This nonhuman primate stopped eating, became progressively blind and incoordinate, and pressed its head against the wall of its cage. Ophthalmic examination was inconclusive. Humane euthanasia was elected, and the animal was submitted for necropsy and histopathological evaluation.

Gross Pathology: The macaque was moderately dehydrated, poorly muscled, and had scant stores of body fat. Other gross necropsy findings were confined to the brain. The meninges covering the dorsal aspect of the cerebrum were diffusely congested. Effacing the cerebral cortex of the left occipital lobe, there was 3 x 2 x 2 cm, well demarcated, expansile mass. The mass was unencapsulated, friable, and tan with multifocal pale areas. There was cerebellar coning consistent with increased intracranial pressure

Laboratory Results: Bacterial culture of a swab of the meninges was negative.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Cerebrum, left occipital lobe: Astrocytoma, high grade, Rhesus macaque.

Astrocytomas generally occur as soft tissue masses in the substance of the cerebral hemispheres, and produce a spectrum of clinical signs based on their exact location. The majority of astrocytomas are well-differentiated with a relatively uniform population of transformed astrocytes having oval nuclei, little heterochromatin and poorly defined cell borders. The tumors can be graded, but regardless of grade there is a background of astrocytic processes between neoplastic nuclei. Higher grade astrocytomas are characterized by increasing nuclear anaplasia, mitotic activity and vascular proliferation. In the adjacent parenchyma, endothelial cells may form glomeruloid proliferations within vascular lumina. These are prominent in high grade astrocytomas, and were present in this case. The highest grade astrocytomas are usually very cellular, and have a mixture of firm white areas, and softer yellow foci of necrosis. These latter features, especially the presence of necrosis, have given rise to the term glioblastoma multiforme. Immunohistochemistry performed by AFIP was positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and negative for S100, synaptophysin, cytokeratin, and vimentin.

Spontaneous astrocytomas are common in humans, but have been regarded as quite rare in most domestic animals. They are most frequent in older mice, rats and dogs. Brachycephalic dogs, especially Boxers, have an incidence approaching that of man. They are also common in VM and BRVR mice. The etiology is unknown, although there may be a genetic component.

Two cases of spontaneous astrocytomas in macaques (a rhesus and a cynomolgus monkey) were reported in 1992. One glioblastoma multiforme was induced in a rhesus monkey after 892 days of having its head exposed to high dose irradiation, and JC virus-induced astrocytomas have been report in owl and squirrel monkeys. Since neoplasms generally are more common with age, the low frequency of astrocytomas in nonhuman primates may be a reflection of relatively young animals being examined. The exact age of this animal was unknown, although it was wild caught and arrived as an adult in 1990 at the National Institutes of Health.

AFIP Diagnosis: Cerebrum: Astrocytoma, high grade (glioblastoma multiforme), Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), non-human primate.

Conference Note: This case has classic features of glioblastoma multiforme, which is often simply called high grade astrocytoma. These features include high cellularity, pleomorphism, necrosis, subpial spread, cortical infiltration, necrosis surrounded by "pseudopalisades" and areas of glomerulus-like endothelial proliferation. Recent evidence suggests that vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) is secreted by malignant astrocytes perhaps in response to hypoxia.

Contributor: National Institutes of Health, NCRR/VRP, 28 Library Dr. MSC 5230, Bethesda, MD 20892-5230.

References:

1. Cordy DR.: Tumors of the Central Nervous System and Eye, 430-435. In Moulton JE (ed), Tumors in Domestic Animals, 2nd ed. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, 1978.

2. HogenEsch H; Broerse JJ; Zurcher, C.: Neurohypophyseal Astrocytoma (Pituicytoma) in a Rhesus Monkey (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol 29(6): 1992.

3. Jortner BX; Percy DH: The Nervous System, 379-385, In Benirschke K, Garner. FM, Jones TC (eds), Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Springer-Verlag, New York, New York, 1978.

4. London WT; Houff SA; McKeever PE; et. al: Viral-induced astrocytomas in squirrel monkeys, Prog Clin Biol Res 105:227-237, 1983.

5. Major EW; Vacante DA; Traub RG; London WT; et.al: Owl monkey astrocytomas cells in culture spontaneously produce infectious JC virus which demonstrates altered biological properties., J Virol 61(5):1435-1441, 1987.

6. Morgan KT; Alison RH: Gliomas, Mouse, 123-130. In Jones TC; Mohr U; Hunt RD (eds.): Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Springer-Verlag, New York, New York, 1988.

7. Cotran, RS; Kumar, V; Robbins, SL: Robbins, Pathologic Basis of Disease, 5th ed., W.B. Saunders, pg. 1342, 1994.

8. Yanai T; Teranishi M; Manabe S; et. al: Astrocytoma in a cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Vet Pathol 29(4): 1992.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #185, 186, 1043, 1464, 1513, 1514, 2831, 3719, 9269.

Signalment: Adult female tamarin.

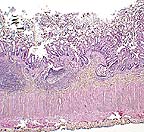

Necrotizing colitis in a tamarin

monkey. (HE, 40X, 73K)

Necrotizing colitis in a tamarin

monkey. (HE, 40X, 73K)

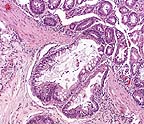

Crypt herniation in a measles-infected

tamarin. (HE, 100X, 106K)

Crypt herniation in a measles-infected

tamarin. (HE, 100X, 106K)

History: A wild-caught female tamarin, housed in a biomedical research colony, was found dead. She had experienced severe diarrhea, which responded temporarily to supportive therapy (fluids and karo syrup).

Gross Pathology: The monkey is mildly dehydrated, with normal muscle mass and scant body fat stores. The parietal peritoneum is mildly thickened, with a granular appearance. Multiple filariid nematodes are present within the abdominal cavity. Multiple 3-4 mm nodules are visible from the serosa of the terminal ileum; these are diverticula of the mucosa, many of which contain embedded heads of acanthocephalid parasites. Numerous acanthocephalids are also attached to the mucosa of the cecum and the cecal-colic junction. The mucosa of the cecum and colon is reddened, and mesenteric lymph nodes are mildly enlarged. There is mucoid fluid in the stomach and normal ingesta in the small intestines and cecum; the colon is empty.

Laboratory Results: Campylobacter sp. was recovered from the colon. The intra-abdominal filarid nematodes were identified as Dipetalonema sp. The acanthocephalids were identified as Prosthenorchis elegans. Additionally, tapeworm proglottids were found in the intestinal contents.

The colon was positive for measles antigen by immunohistochemistry, using a "measles blend", a combination of 2 monoclonal antibodies directed against measles hemagglutinin and matrix protein (Chemicon International, Inc., catalog #MAB8920).

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Colon: Colitis, acute, diffuse, moderate, with epithelial syncytial cells and intranuclear inclusion bodies. Etiology: Paramyxovirus infection, most likely measles.

This case occurred during an outbreak of measles among the macaques housed in the same building. Affected macaques manifested a cutaneous rash, fever, and coughing. The diagnosis of measles was confirmed by serology, and in one case, a skin biopsy with typical dermal inflammation and epithelial syncytia. The source of the infection has not been identified. At the time of the outbreak, related clinical disease was not recognized in New World monkeys housed in the same building.

The histologic changes in the colon (epithelial necrosis, epithelial syncytial cells and intranuclear inclusion bodies) are consistent with infection with a paramyxovirus. A careful microscopic search of multiple organs, including spleen, liver, lymph nodes and lung failed to demonstrate involvement of any other organ. Callitrichids are susceptible to parainfluenza virus, measles (morbillivirus) virus, and Paramyxovirus saguinus. Parainfluenza is characterized clinically by upper and lower respiratory tract disease. Measles in New World primates can manifest as a respiratory tract disease or an enteritis. Paramyxovirus saguinus is reported to cause gastroenteritis in marmosets and tamarins.

Based on the histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and temporal/spatial association with a measles outbreak in other primate species, we consider this most likely an example of measles infection apparently restricted to the intestinal tract. While we cannot completely exclude the possibility of cross-reactivity of the measles monoclonal antibodies with Paramyxovirus saguinus, we consider it highly unlikely.

A measles epidemic has been reported in a marmoset colony, with high morbidity and mortality. Clinical signs included edema of the upper eyelids, progressive lethargy, nasal discharge, focal erythema and edema, and maculopapular rash. Histologically, there was interstitial pneumonia with giant cells and intranuclear inclusions. Giant cells were also found in lymph nodes, spleen, and gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of the colon. In another reported outbreak of measles in tamarins, Saguinus mystax, rash was not observed. Measles infections in New World monkeys can also the characterized, as in this case, by gastrointestinal disease, with epithelial necrosis. Syncytial giant cells form in mucosal epithelium, lamina propria, and GALT.

This case illustrates that measles infection in New World primates may present differently than in macaques. Clinically, this tamarin had severe diarrhea, with no detected rash. Histologically, the infection was apparently confined to the intestinal tract; syncytia were not found in other organs (lymph nodes, spleen, liver, urinary bladder, lung). During this outbreak, one other adult tamarin died, with similar histologic and immunohistochemical findings; a third animal died of other causes, but manifested mild intestinal involvement with few syncytial cells in the mucosal epithelium.

Intra-abdominal filarid nematodes are commonly encountered in wild-caught tamarins; the infection appears to be of minimal clinical significance. Histologically, there is a mild chronic peritonitis. Infection with Prosthenorchis elegans is likewise commonly encountered in wild caught animals. Heavy infestation can result in clinical disease and death. There is no treatment. The intermediate host is the cockroach. In cockroach infested vivariums, there remains the threat of intra-colony spread. In this case, there was no evidence that the Campylobacter sp. infection was clinically significant. Campylobacter sp. is commonly isolated from monkeys in our facility, both with and without diarrhea.

AFIP Diagnosis: Colon: Colitis, necrotizing, subacute, diffuse, moderate, with crypt herniation, lymphoid depletion, syncytial cells, and intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, tamarin, primate.

Conference Note: Using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded colon from this monkey, the Department of Cellular Pathology of the AFIP detected morbilliviral RNA by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Southern blot using a measles virus-specific probe was positive confirming that measles virus was the etiologic agent.

Measles virus is a morbillivirus of the paramyxovirus family. It has an envelope that contains an hemagglutinin that binds to host cells, and a small glycoprotein that has hemolytic activity and mediates penetration of the virus into the host cytosol. Measles virus is spread by respiratory droplets and multiplies within upper respiratory epithelial cells and mononuclear cells, including B and T lymphocytes and macrophages. A transient viremia spreads the virus throughout the body and may cause croup, pneumonia, diarrhea with protein-losing enteropathy, keratitis, encephalitis, and hemorrhages. T-cell mediated immunity usually develops to control the viral infection and often produces a rash which is caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to measles antigen in the skin. The rash does not develop in animals with deficient cell-mediated immunity.

Contributor: Pathology Service, Diagnostic & Surgical Services, Veterinary Resources Program, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 20892.

References:

1. Cicmanec, JL: Medical problems encountered in a callitrichid colony. In Kleinman, DG (eds): The Biology and Conservation of the Callitrichidae, Washington Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 331-336, 1977.

2. Fraser, CEO; et. al: A paramyxovirus causing fatal gastroenteritis in marmoset monkeys. Primates in Medicine, 10: pp. 261-270, 1978.

3. Levy, BM; Mirkovic, RR: An epizootic of measles in a marmoset colony. Lab An Sci, 21, pp. 33-39, 1971.

4. Lowenstine, LJ: Measles Virus Infection, Non-human Primates. In Jones, TC; Mohr, U; Hunt, RD (eds): Nonhuman Primates 1 (Monographs on Pathology of Laboratory Animals), ILSI, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 108-118. 1993.

5. Potkay, S: Diseases of the Callitrichidae: A Review. J of Med Primatology, 21, pp. 189-236, 1992.

6. Cotran, RS; Kumar, V; Robbins, SL: Robbins, Pathologic Basis of Disease, 5th ed., W.B. Saunders, pp. 346-347, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: None

Signalment: Common marmoset.

History: Several similarly housed marmosets presented clinically with a syndrome similar to "marmoset wasting syndrome" (weight loss and failure to thrive).

Gross Pathology: In affected animals, gross pancreatic lesions were minimal and indicative of chronic pancreatitis.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Pancreas: Pancreatitis, lymphocytic, eosinophilic, chronic, multifocal, mild to moderate with intraductal nematodes (Trichospirura leptostoma).

Marked variation is present in the severity of lesions between affected animals. Lesions consist of the following: Multifocally, pancreatic ducts are greatly dilated and contain numerous parasites. The parasites are round, approximately 125 to 150 in diameter, have a ridged cuticle, a pseudocoelom and contain tubular organs (nematode). Numerous embryonated ova are present in the uterus of female parasites. Ductular epithelium is multifocally attenuated and periductal tissue is fibrotic and hypercellular. The cellular infiltrate is composed primarily of lymphocytes with fewer eosinophils. The cellular fibrous tissue extends into exocrine tissue where there is loss of acinar tissue. The morphology and intraductal location of the nematodes are most suggestive Trichospirura leptostoma infection.

Marmoset wasting syndrome is a loosely described disease entity that appears to be multifactorial. In this group of animals, failure to thrive was correlated with the presence of a verminous pancreatitis. Differential diagnosis included nematode larval migration (ex: Strongyloides sp), Angiostrongylus sp. infection and pancreatic trematodiasis.

AFIP Diagnosis: 1. Pancreas: Pancreatitis, chronic-active, multifocal, moderate, with intraductal adult and larval spirurid nematodes, common marmoset, primate. 2. Urinary bladder: Cystitis, transmural, acute, multifocal, moderate.

Conference Note: The spirurid nematode Trichospirura leptostoma has been found within the pancreatic ducts of several species of wild South American nonhuman primates. Infections of captive primates have been reported occasionally. These animals become infected when they ingest an arthropod intermediate host (most likely cockroaches) containing the encysted infective larval stage (L3). The L3 migrate to the pancreatic ducts where they mature into adults. Embryonated eggs travel down the pancreatic duct into the intestine and are passed in the feces. The prepatent period is approximately 7 to 9 weeks. The presence of the adults within the pancreatic ducts may cause compression atrophy of the lining epithelium, pancreatitis, and acinar atrophy.

Characteristic features of spirurid nematodes include coelomyarian, polymyarian musculature, esophagus with anterior muscular and posterior glandular portions, intestine lined by uninucleate cells with a long or medium length microvillar border, prominent lateral chords and thick-shelled embryonated eggs. Excretory canals are present in the lateral chords of this spirurid.

The acute transmural cystitis is probably not related to the parasitism. Special stains failed to identify an etiologic agent.

Contributor: Department of Comparative Medicine, Health Sciences; Box 357190, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7190.

References:

1. Illgen-Wilcke-B. Beglinger-R. Pfister-R. Heider-K. Studies on the development cycle of Trichospirura leptostoma (Nematoda: Thelaziidae). Parasitol-Res., 786(6). pp. 509-12, 1992.

2. Benirschke, K; Garner, FM; Jones, TC (eds): Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Vol II, Springer-Verlag, pg. 1665, 1978.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: None

Signalment: 55-week-old female Wistar rat.

Infiltrating cords of ependymoma

in the spinal cord of a Wistar rat. (HE, 100X, 115K)

Infiltrating cords of ependymoma

in the spinal cord of a Wistar rat. (HE, 100X, 115K)

Rosette formed around neuropil

characteristic of ependymoma. (HE, 400X, 66K)

Rosette formed around neuropil

characteristic of ependymoma. (HE, 400X, 66K)

History: Rat was in an untreated group on an 104 week carcinogenicity study. The rat was sacrificed during the 48th week of the study due to lameness in both hind limbs.

Gross Pathology: This lesion was not observed at necropsy, as spinal cord sections were left intact in the segments of the vertebral column.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Glioma, anaplastic.

This spinal cord neoplasm presented a diagnostic challenge for our pathology group. Use of this recently-introduced Wistar-derived strain for carcinogenicity studies has not been reported. References to spinal cord tumors in other rat strains are brief and infrequent, and the occurrence of spinal cord neoplasms is extremely rare in our extensive experience with Sprague-Dawley rats. The cells of this neoplasm are forming pseudorosettes and cords in some areas, however, the cells are quite pleomorphic, true rosette formation is not evident, and cell margins are often distinct. Depending on the section, the participant may see a single well-delineated mass, or two masses separated by a fibrous stroma that represent branching by the main tumor. Mitotic activity is very high, and clusters and cords of cells are often surrounded by an amorphous eosinophilic matrix. Common features of other central nervous system neoplasms, such as astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, meningioma, ependymoma, and granular cell tumor were not evident. This neoplasm may represent an extremely anaplastic variant of a glial tumor, and as such, be difficult to categorize according to classical criteria. Cytochemical studies may be contributory, but were unavailable to us.

AFIP Diagnosis: Spinal cord: Ependymoma, Wistar rat, rodent.

Conference Note: The participants agreed with the contributor's comments on this difficult case. The Department of Neuropathology of the AFIP also reviewed the case. The histopathologic features are those of a neuroepithelial neoplasm with glial processes forming neuropil-prominent perivascular pseudorosettes. The differential diagnosis based on the H&E sections was ependymoma versus paraganglioma. The absence of immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin supports ependymoma. Thus, we agree with the contributor that the neoplasm is in the glial group but favor the more specific diagnosis of ependymoma. Other immunohistochemical and histochemical stains were noncontributory. The hypercellularity, frequent mitoses, necrosis and vascular proliferation are indicators of aggressive behavior.

Ependymomas are rare neoplasms of neuroectodermal origin that develop from the ependymal lining of the ventricles of the brain and central canal of the spinal cord. They have been reported in rats, cats, dogs, non-human primates, cattle, horses, deer, and fish. Ependymomas are usually slow-growing and frequently cause extensive tissue damage by compressing the adjacent neuropil. Anaplastic varieties can infiltrate the brain or spinal cord and metastasize via the cerebrospinal fluid. Obstruction of the fourth ventricle can result in hydrocephalus.

Ultrastructurally, ependymal cells have intercellular tight junctions. Some may be ciliated and contain blepharoplasts. Blepharoplasts can sometimes be demonstrated with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH). Immunohistochemically, ependymomas are variably stained for vimentin, GFAP, and keratin.

Contributor: Corning Hazleton Wisconsin, P.O. Box 7545, Madison, WI 53707.

References:

1. Solleveld, HA; Gorgacz, EJ; and A. Koestner: Central Nervous System Neoplasms in the rat. Guides for Toxicologic Pathology. STP/ARP/AFIP, Washington, D.C., 1991.

2. Summers, BA; Cummings, JF; de Lahunta, A: Veterinary Neuropathology, Mosby, pp. 375-376, 1995.

3. Dagle GE; Zwicker GM; Renne RA: Morphology of spontaneous brain tumors in the rat., Vet Pathol 16(3):318-24, 1979.

4. Jubb, KVF; Kennedy, PC; Palmer, N: Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol. 1, 4th ed., pp. 433-434, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #1765, 1766, 2558, 8389, 20966-8, 21350,21351.

Lance Batey Captain, VC, USA Registry of Veterinary Pathology* Department of Veterinary Pathology Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615 Internet: Batey@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.