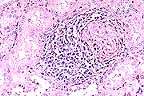

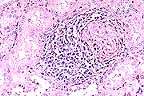

Lymphoplasmacytic periglomerular

inflammation in the kidney of a 6-month-old pig. (HE, 200X, 56K)

Lymphoplasmacytic periglomerular

inflammation in the kidney of a 6-month-old pig. (HE, 200X, 56K)Signalment: 6-month-old pig of unknown breed.

Lymphoplasmacytic periglomerular

inflammation in the kidney of a 6-month-old pig. (HE, 200X, 56K)

Lymphoplasmacytic periglomerular

inflammation in the kidney of a 6-month-old pig. (HE, 200X, 56K)

History: Slaughter house reports seasonal incidence (high in summer) of kidney lesions. Lesions consist of white spots or intermixed white and red spots.

Gross Pathology: Two kidneys are received in 10% neutral buffered formalin and are similar. Each has multiple, cortical, 1-3 mm, white foci and focal cortical indentations (suspected fibrosis).

Laboratory Results: Kidney sections were immunohistochemically stained with polyvalent antisera (serovars canicola, grippotyphosa, hardjo, copenhageni, and pomona) following the procedure of Miller, D.A. (1989). Numerous spiroid bacteria are seen within tubular lumens and rarely with the interstitium.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: 1. Interstitial nephritis, lymphocytic and histiocytic, multifocal, moderate, chronic. 2. Pyelonephritis, suppurative, multifocal, moderate, acute.

The capsular surface is irregular due to multifocal interstitial fibrosis and accompanying infiltrates of lymphocytes and histiocyte. Adjacent tubules are frequently lined by flattened epithelium or by tall, lightly basophilic epithelium (regenerative). Occasional tubules are dilated and contain numerous neutrophils. Inflammation is principally confined to the cortex. The epithelial lining of the renal pelvis is often vacuolated.

Lesions indicate two separate processes: interstitial nephritis and pyelonephritis. The interstitial component is similar to that described for swine infected with Leptospira interrogans. Numerous intratubular and few interstitial leptospires are seen on immunohistochemical stains. The cause of the ascending tubular infection was not determined (no fresh tissue received).

Leptospirosis continues to be a significant disease in swine, causing abortions and stillbirths in pregnant animals and septicemia with secondary localization in the kidney in juvenile and occasionally adult animals.

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephritis, tubulointerstitial, chronic-active, diffuse, moderate, breed not specified, porcine.

Conference Note: The Warthin-Starry method demonstrated numerous, delicate, 5 to 20 m long spirochetes consistent with Leptospira sp. within the proximal renal tubules. The single diagnosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis was chosen because the participants were not certain that two separate pathologic processes were involved.

Leptospirosis is an important bacterial disease of man and many animal species. It is caused by slender, helical, motile, spirochetes that measure approximately 0.2-0.3 m in diameter and 6-30 m in length. The pathogenic leptospires belong to any of 180 known serovars within 19 serogroups of Leptospira interrogans. Each serovar is adapted to and may cause disease in a particular maintenance species although they may cause disease in any other species, the incidental hosts.

The natural reservoir of pathogenic leptospires is the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney and in certain maintenance hosts, the genital tract. Transmission can be direct through urine splashing, in post-abortion discharges, venereally, through milk or transplacentally. Indirect transmission is through contamination of the environment with infected urine. Leptospires penetrate exposed mucous membranes or through abraded or water-softened skin and then disseminate throughout the body. After a brief leptospiremia, the development of opsonizing and agglutinating antibodies clear the leptospires from all sites except those penetrated poorly by antibody including proximal convoluted tubules, cerebrospinal fluid, vitreous humor, and for certain serovars, the genital tract of maintenance host.

Most leptospiral infections are subclinical and detected only by serology or lesions of interstitial nephritis at slaughter or necropsy. Acute and often severe disease may occur during the leptospiremic phase, particularly in young animals. Acute clinical disease is often characterized by jaundice, hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, pulmonary congestion, and occasionally meningitis. Anemia initially is due to hemolysin production and later is caused by an antibody-mediated reaction against leptospiral antigen coated erythrocytes. Jaundice may result from both hemolysis and toxic or ischemic hepatocellular injury. Chronic disease can occur in the post-septicemic phase in the form of abortion, stillbirth, infertility, interstitial nephritis or recurrent uveitis. Localization of leptospires in the kidney is associated with focal or diffuse interstitial nephritis and with acute, transient tubular degeneration.

Leptospirosis in swine continues to be a cause of serious economic loss and a potential hazard to human health. Leptospires frequently cause interstitial nephritis grossly characterized by the presence of multiple white foci in the renal parenchyma which results in condemnation. The principle clinically significant aspects of the disease in swine are abortion and the birth of weak piglets. The usual pattern in pregnant sows is to deliver 1 to 3 weeks prematurely, with some of the fetuses mummified, some more recently dead, and others born alive, only to die shortly afterward. Leptospira interrogans serovar pomona type kennewicki and serovar grippotyphosa are the most frequent isolates in cases of porcine leptospirosis in the United States.

Contributor: Dept. Of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-7040.

References:

1. Miller, D.A., Wilson, M.A., and Kirkbride, C.A.: Evaluation of multivalent leptospira fluorescent antibody conjugates for general diagnostic use. Journal Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 1:146-149, 1989.

2. Miller, D.A., Wilson, M.A., Owen,W.J. and Beran, G.W.: Porcine leptospirosis in Iowa. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 1:171-175, 1990.

3. Scanziani, E., Sironi, G. And Mandelli, G.: Immunoperoxidase studies on leptospiral nephritis of swine. Veterinary Pathology 26:442-444, 1989.

4. Chappel, R.J., Prime, R.W., Millar, B.D., Mead, L.J., Jones, R.T., and Adler, B.: Comparison of diagnostic procedures of porcine leptospirosis. Veterinary Microbiology 30:151-163, 1992.

5. Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy, P.C., Palmer, N.: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed. Vol. 2., pp. 503-511, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #654, 4732, 5194, 10363, 10364, 10365, 11669, 13843.

Signalment: 11-year-old female Quarterhorse.

History: Horse was treated for colic; next day owner noted dark brown urine. When presented on the third day of illness to the University of Tennessee Veterinary Clinic, mucous membranes were icteric and brown and the urine was dark brown. A CBC revealed a PCV of 14%, Heinz bodies and methemoglobinemia of 43% (normal <3%). With Vitamin C therapy and two blood transfusions, hemolytic anemia continued along with intermittent ventricular tachycardia. The owner elected euthanasia after two days of therapy.

The pasture contained several red maple trees; several branches had been blown down in a storm the week before the owner noticed that the horse was ill. All of the leaves were missing from several of the branches.

Gross Pathology: This 500 kg horse has a generalized bronze discoloration throughout the subcutis, muscles, heart, lung and peritoneum. The liver is green/brown with a prominent reticular pattern. Kidneys are diffusely black/green. The stomach contains a large amount of sweet smelling plant material; there is a 2.5 x 0.5 cm ulcer along the margo plicatus.

Laboratory Results: None.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Hemoglobinuric nephrosis, equine due to red maple leaf poisoning.

The toxic agent in dry red maple (Acer rubrum) leaves is unknown, but is believed to be an oxidant responsible for the conversion of ferrous iron in hemoglobin to the ferric form (methemoglobin) and Heinz body formation (believed to be precipitated methemoglobin). The subsequent osmotic damage to red blood cells results in their destruction and splenic sequestration.

In this case, these events affecting erythrocytes were manifested clinically by marked hemolytic anemia (14% PCV), methemoglobinemia (43% - normal <3%) and hemoglobinuria. Other causes of intravascular hemolysis in the horse include autoimmune hemolytic anemia, nitrate and copper poisoning, and equine infectious anemia. Hemolytic anemia with methemoglobinemia was presumed to be due to red maple leaf poisoning because of known ingestion of dead red maple leaves.

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Necrosis, tubular, acute, multifocal, moderate, with granular, intratubular, brightly eosinophilic material, and hemoglobin crystals, Quarterhorse, equine.

Conference Note: Red maple leaf (Acer rubrum) poisoning was first reported in 1981 as the cause of acute hemolytic anemia in horses from northeastern the United States. The hemolytic syndrome was characterized by methemoglobinemia and with time, Heinz body formation. The toxic agent has not been identified, but based on clinical pathologic findings, is believed to be an oxidizing compound. Interestingly, the toxin is not present in fresh maple leaves, only in those that have been dried.

As the contributor noted, erythrocyte oxidation results in formation of methemoglobin. Methemoglobin formation alone, does no cause hemolysis. The sulfhydryl groups of the globin molecule also are susceptible to oxidation and formation of mixed disulfides. These disulfide bonds initially may be reversible, but with progressively severe oxidation, irreversible damage to the globin molecule occurs. The resulting denaturation causes precipitation of methemoglobin and formation of spherical, refractile Heinz bodies that attach to and damage the erythrocyte plasma membrane, rendering it more susceptible to osmotic damage and splenic sequestration.

Contributor: University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Dept. of Pathology, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Rm A201, 2407 River Dr., Knoxville, TN 37996-4500.

References:

1. George, LW et al: Heinz body anemia and methemoglobinemia in ponies given red maple (Acer rubrum L.) leaves, Vet Pathol 19, pp. 521-533, 1982.

2. Stair, EL et al: Suspected red maple (Acer rubrum) toxicosis with abortion in two percheron mares, Vet Hum Toxicol 35, pp. 229-230, 1993.

3. Tennant, B et al: Acute hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, and Heinz body formation associated with ingestion of red maple leaves by horses, J Am Vet Med Assoc 179, pp. 143-150, 1981.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #1539, 6348, 6349.

Signalment: Female Swiss Webster mouse.

History: Mouse was injected with 200 cercaria of Schistosoma mansoni on 18 January 1996 and was found dead in its cage on 3 April 1996.

Gross Pathology: The liver was yellow-brown to tan and had a granular appearance.

Laboratory Results: None.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Liver: hepatitis, chronic, portal and bridging, multifocal, moderate, with granuloma formation, trematode eggs, pigment, and intravascular trematode parasites - etiology consistent with Schistosoma mansoni.

Schistosomes are digenetic trematodes that live within the blood vessels of their hosts. Their distribution is determined by the distribution of their intermediate hosts (a nonoperculated snail in the case of S. mansoni). Schistosome eggs hatch in the water releasing a ciliated miracidium which penetrates the snail. Cercariae develop in the snail and are released in the water where they are ingested or penetrate the skin to infect the host. Metacercaria migrate to the liver, pair within the portal circulation, reach maturity, and deposit eggs which penetrate capillary walls and leave the body via the feces or the urine to continue the life cycle.

Schistosomiasis is one of the most common causes of human morbidity and mortality. The adult parasites live in the host's veins and can incorporate host antigens, avoiding an immune response. The eggs that remain in tissues cause inflammation that progresses from neutrophils and eosinophils to granulomas with multinucleate giant cells. Urinary schistosomiasis has been associated with carcinomas of the urinary bladder in man and nonhuman primates.

AFIP Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, portal and bridging, chronic, multifocal, moderate, with granulomas, trematode eggs, and intravascular trematodes, Swiss-Webster mouse, rodent, etiology consistent with Schistosoma mansoni.

Conference Note: Schistosomiasis is a snail-borne fluke infection prevalent in domestic animals, nonhuman primates, and humans in Asia, Africa, and other tropical and subtropical areas. Species that parasitize mammals include those of the genera Schistosoma, Hetrobilharzia and Orientobilharzia. The only schistosome of importance in the United States is Heterobilharzia americana, which has been reported in raccoons, bobcats and dogs in the southern United States. Schistosomes are different from other flukes in that they live in blood vessels, have separate sexes, have nonoperculated eggs with a spine, and do not have an encysted metacercaria stage.

Adult schistosomes, while alive in the veins, generally provoke little or no host response because they incorporate host antigens (primarily blood group antigens) into the outer membranous tegument and are therefore recognized as "self." Phlebitis with intimal proliferation and occasionally thrombosis may result from the presence of adult flukes. Vascular lesions are more severe when the adult worms die or are trapped at unusual sites. Eggs that escape into the tissues stimulate considerable inflammation. Penetration of the skin by cercariae results in urticaria, itching and formation of tiny nodules which elevate the epidermis. In humans, this often is caused by avian schistosomes and is commonly called "swimmer's itch."

The diagnosis of schistosomiasis can be readily made on histopathologic sections with the finding of intravascular trematodes and/or the characteristic spiny, non-operculated eggs.

Contributor: Naval Medical Research Institute, Attn: Pathobiology Code 21, 8901 Wisconsin Ave. Bethesda, Maryland.

References:

1. Jubb, KVF, Kennedy, PC, Palmer, N: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 77-79. 1993.

2. Bartsch, RC, Ward, BC: Visceral lesions in raccoons naturally infected with Heterobilharzia americana.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #4156, 19324, 19325, 21012, 21013, 21014, 21015, 21016, 21019.

Signalment: Bovine, mixed breed beef, approximately 3-months-old.

History: Several calves and cows were acutely ill. Several died in the last 4 months. This calf was alive when sent to the laboratory but died on the way. A bottle of MSMA herbicide (monosodium methanearsonate) was eventually found to have a pin-hole leak and had been dripping into a meal supplement in a storage shed.

Gross Pathology: The rumen had dark red blotches diffusely across the epithelial surface but the serosa was grossly normal. The abomasum contained milk curds and its mucosa was diffusely fiery red and a few Haemonchus sp. were present. The reticulum and omasum were grossly normal. The intestine and colon contained brown watery material and their mucosae were dull brown with a red tinge.

Laboratory Results: Rumenal contents were negative for arsenic. The liver was positive for arsenic at 1.92 ppm.

Intestinal smears were negative for Clostridium and F.A. tests for rotavirus, coronavirus, and BVD were negative. The intestine was negative for Salmonella.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Superficially necrotizing subacute rumenitis (and omasitis) due to arsenic toxicity.

Whole blood from another sick cow had elevated arsenic at 0.14 ppm. Normal bovine liver arsenic levels are 0.004-0.4 ppm. High levels are 1.0-5.0 ppm and acute toxic levels are 2.0-15 ppm. Normal blood arsenic is 0.03-0.05 ppm and acute toxicity occurs from 0.17-6.7 ppm. Arsenic is rapidly cleared from the body (half-life 1.5 days). It is directly corrosive to the GI tract but also inactivates the sulfhydryl groups of oxidative enzymes within capillary endothelial cells; the liver, kidney and intestine are most sensitive. Capillaries become more permeable and the muscle layer of small arteries relaxes. The GI mucosa may slough away from underlying edema. In this calf, the abomasum and intestine were normal except for congestion and the other organs were normal microscopically. Fungal stains on the rumen and omasum were negative. The omasal lesions (not submitted on most slides) were much milder and more multifocal than those in the rumen.

The people on the farm had been vaguely ill and had been butchering and eating the previous dead animals. Frozen livers from 2 of these animals that died earlier were tested and found to be negative for arsenic (<0.5 ppm). One muscle sample (steak) was also negative.

AFIP Diagnosis: Rumen: Rumenitis, necrotizing, acute, diffuse, severe, with hemorrhage, edema, and focal arteritis, mixed breed, bovine.

Conference Note: Animals may be poisoned with arsenic through ingestion or percutaneous absorption. The most common sources of arsenic are insecticides and herbicides containing sodium arsenite, lead arsenate, or arsenic pentoxide. Poisoning occurs when animals gain access to recently sprayed pastures. Ore deposits frequently contain high levels of arsenic and poisoning may occur when pasture and drinking water are contaminated by exhaust from smelters. Other sources include wood preservatives and injectable preparations to control blood parasites.

In domestic animals, arsenic does not stay in the tissues very long. It is partially methylated in the liver and kidney and is rapidly excreted in urine, feces, bile, milk, saliva, and sweat. Arsenic may cross the placental and blood-brain barriers in small amounts. The milk from poisoned cows is toxic for humans and calves, but meat is considered safe for consumption.

The organs most susceptible to inorganic arsenic toxicity are the brain, lungs, liver, kidney, and alimentary mucosa. The lesions produced by acute poisoning can largely be explained on the basis of vascular injury. The lesions most commonly observed are severe congestion, edema, hemorrhage and vascular necrosis. Lesions in the stomach and intestines usually include intense congestion with edema, hemorrhage, and ulceration. Brain lesions usually include moderate, diffuse cerebral edema and petechiation. A peripheral neuropathy has been described. Chronic arsenic poisoning usually has the same anatomic distribution of lesions as acute poisoning. The application of arsenicals to the skin may result in a chronic dermatitis or, if absorption is rapid, systemic toxicity. The dermatitis is characterized by intense erythema, necrosis, and sloughing.

Organic arsenicals, p-aminophenylarsonic acid (arsanilic acid) and 3-nitro-4-hydroxyphenylarsonic acid (3-Nitro), are commonly used as feed additives for swine, to promote growth and control enteric disease. Two syndromes related to accidental poisoning by these compounds has been described. Unlike inorganic arsenicals, lesions are mostly confined to the central nervous system.

Contributor: Arkansas Livestock and Poultry Commission, #1 Natural Resources Dr. Little Rock, AR 72205.

References:

1. Hatch, RC: Poisons causing abdominal distress or liver or kidney

damage. In: Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 6th Ed.,

edited by NG Booth and LE McDonald, ISU Press, Ames, pp.1102-1107,

1988.

2. Puls, R: Mineral Levels in Animal Health, Sherpa International, British Columbia, Canada, pg. 25, 1990.

3. Jubb, KVF, Kennedy, PC, Palmer, N: Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 359-360, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #3371, 3946, 3947, 3948, 8776.

Lance Batey

Captain, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: Batey@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.