Radiograph of a 6-month-old

eider duck with a metal foreign object in the ventriculus. (31K)

Radiograph of a 6-month-old

eider duck with a metal foreign object in the ventriculus. (31K)

Radiograph of a 6-month-old

eider duck with a metal foreign object in the ventriculus. (31K)

Radiograph of a 6-month-old

eider duck with a metal foreign object in the ventriculus. (31K)

Penny found in the venticulus

of a 6-month old eider duck. (52K)

Penny found in the venticulus

of a 6-month old eider duck. (52K)

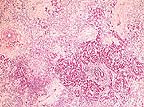

Severe pancreatic atrophy

and fibrosis due to zinc toxicosis in an eider duck. (HE, 200X,

97K)

Severe pancreatic atrophy

and fibrosis due to zinc toxicosis in an eider duck. (HE, 200X,

97K)

Signalment: 6-month-old American eider duck (Somateria mollisima dresseri) male, 1.4 kg.

History: Noted to be depressed (on exhibit); radiograph revealed penny in ventriculus; treated with itraconazole, fluids, baytril, and calcium versonate. There was no improvement over next 10 days. The penny was surgically removed. The duck died 24 hours later.

Gross Pathology: Findings included fibrinopurulent serositis and proventricular rupture.

Laboratory Results: N/A

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Pancreas, fibrosis, diffuse, chronic, severe with occasional acinar cell necrosis and acinar disorganization.

The penny removed from the ventriculus of this duck was too severely eroded to read the year of minting, but the gray metallic center indicates that it is composed primarily of a high zinc alloy with a thin coating of copper as are all pennies minted after 1982 (1). Presumably, the duck ingested the penny from a pond in the exhibit, where it may have been tossed by a zoo visitor. Pancreatic fibrosis and necrosis have been associated with zinc toxicity in ruminants (2), chickens (3,4) and ducks (5,6).

AFIP Diagnosis: 1. Pancreas: Exocrine parenchymal loss, diffuse, moderate, with regeneration, fibrosis and ductular hyperplasia, American eider duck (Somateria mollissima dresseri), avian. 2. Serosa: Serositis, fibrinosuppurative, subacute, moderate to severe, with gram-negative bacilli. 3. Omental adipose tissue: Atrophy, multifocal, moderate.

Conference Note: Cases of zinc toxicosis in animals usually result from ingestion of galvanized fence clips or pennies. The histologic and ultrastructural lesions of experimental zinc toxicity in ducklings, chicks, and sheep have been described.

Several distinct syndromes have been reported following ingestion of zinc-containing objects. A zinc-induced hemolytic anemia has been described in a puppy following ingestion of pennies. An experimental study in sheep suggests that the primary lesion in zinc toxicosis is pancreatic ductular necrosis. The early lesions described in sheep include necrosis of the pancreatic ductular epithelium, periductular inflammation, and interlobular fat necrosis, followed by edema, lobular cystic change, atrophy, fibrosis, and ductular hyperplasia. Necrotizing enteritis and renal tubular necrosis have also been reported in birds.

Ultrastructurally, pancreatic exocrine cells have reduced numbers of zymogen granules, distended rough endoplasmic reticulum, many small cytoplasmic electron dense bodies, large autophagic vacuoles, and necrosis. These lesions reflect interference with pancreatic protein synthesis and membrane integrity.

The fibrinosuppurative serositis in this case was attributed to proventricular rupture.

Contributor: Division of Comparative Medicine Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205.

References:

1. Latimer KS et al. Zinc-induced hemolytic anemia caused by ingestion

of pennies by a pup. JAVMA 195:77-80, 1989.

2. Smith BL and Embling PP. Sequential changes in the development of the pancreatic lesion of zinc toxicosis in sheep. Vet Pathol 30:242-247, 1993.

3. Wight PAL et al. Zinc toxicity in the fowl: Ultrastructural pathology and relationship to selenium, lead and copper. Avian Pathol 15:23-38, 1986.

4. Lu J and Combs Jr, GF. Effect of excess dietary zinc on pancreatic exocrine function in the chick. J. Nutr. 118:681-689, 1988.

5. Van Vleet JF et al. Induction of lesions of selenium-vitamin E deficiency in ducks fed silver, copper cobalt, tellurium, cadmium or zinc: protection by selenium of vitamin E supplements. AJVR 42:1206-1217, 1981.

6. Kazalos EA. Studies on the pathogenesis of pancreatic alterations in zinc toxicosis in ducklings. Ph.D. thesis, College of Vet Medicine, Purdue University, 1984.

7. Droual R et al. Zinc toxicosis due to ingestion of a penny in a gray-headed Chachalaca (Ortalis cinereiceps). Avian Diseases 35:1007-1011, 1991.

8. Zdziarski JM et al. Zinc toxicosis in diving ducks. J Zoo & Wildlife Med 25(3): 438-445, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame # 3365, 14038, 23222, 23298, 23299.

Signalment: 3-year-old red-tailed boa constrictor (Boa constrictor).

History: This boa was part of a colony of over 40 exotic snakes of various species. It had a 5 month history of lethargy, intermittent anorexia, weight loss, and fetid loose feces. On physical examination it had dehydration and petechiation of its oral mucosa and ventral scutes. It was treated with fluids and antibiotics over a period of 2 months without improvement.

Gross Pathology: Marked coelomic and pericardial serous effusions. Diffuse petechiation of fat bodies and subcutis. Focal segment of distal small intestine with severe edema and luminal accumulation of partially adherent thick mucoid material.

Laboratory Results: CBC ( 4 weeks ante-mortem): PCV = 21%, WBC = 1500 cells/ l; Intestinal contents, fungal culture: Small numbers ofTrichosporon beigelii, Aspergillus clavatus; Salmonella culture negative, fecal floatation negative; IFA for Giardia and Cryptosporidium negative.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: 1. Necrotizing enteritis, heterophilic and granulomatous, moderate, focal, with intra-lesional fungal hyphae and yeast forms - presumptive etiology: Aspergillus clavatus, Trichosporon beigelii.

2. Intra-cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies in most cell types - Boid inclusion body disease.

Inclusion body disease (IBD) affects various species of boid snakes and usually manifests as progressive debilitation, anorexia, weight loss, regurgitation, and neurologic signs. The presence of the typical, well-defined intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies is often associated with cellular degeneration in various tissues, most commonly in the CNS, where a non-suppurative encephalomyelitis can also be observed. Various secondary infections are frequently associated with IBD, such as pneumonia and nephritis. In this boa, encephalitis was not noted, although inclusions were numerous in the brain, and were associated with degeneration. The animal also had a mycotic enteritis affecting a focal segment of distal small intestine. The morphology of the fungal elements (pleomorphic hyphae, yeast forms) was compatible with both the Aspergillus clavatus and Trichosporon beigelii organisms obtained by fungal culture of the intestinal contents. The boa probably developed fungal enteritis from the changes in gut flora induced by prolonged antibiotic treatment; IBD may have been a predisposing factor. Electron microscopy of liver tissue revealed that the inclusions contained granular homogenous osmiophilic material. Lined around the periphery, and occasionally inside the inclusions were numerous clathrin-coated pinocytotic vesicles. A few particles consistent with type C retroviruses, measuring 95-110 nm, were observed in the intercellular spaces, sometimes budding from the cell membrane. The particles were similar to those previously reported in snakes with IBD (see reference).

AFIP Diagnosis: 1. Intestine: Enteritis, ulcerative, necrotizing, granulomatous, multifocal, severe, with fungal hyphae, red-tailed boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), reptile, etiology consistent with a zygomycete. 2. Intestinal epithelium; lymphocytes; intestinal ganglion cells of myenteric plexi: Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies.

Conference Note: The inclusions in submitted tissues are eosinophilic to amphophilic, range up to 10 microns in diameter, and did not appear to be associated with degenerative or inflammatory changes. The morphologic features of the fungus are consistent with the those of the Class Zygomycetes and not with Aspergillus or Trichosporon spp. These features include broad, thin-walled, infrequently septate, pleomorphic hyphae that range from about 5 to 20 m in width and irrgeular right angle branches. The fact that the hyphae stain well with H&E is also characteristic of a zygomycete.

Inclusion body disease of boid snakes has been recognized for over 20 years in private and zoological collections in the United States. The disease affects only snakes of the Family Boidae including both boa constrictors and pythons. The disease is characterized by the formation of intracytoplasmic inclusions in the epithelial cells of all major organs and neurons in the central nervous system. Clinical symptoms include head tremors, disorientation, incoordination, and regurgitation. Ultrastructurally, a type C retrovirus has been associated with the lesions. The presence of a retrovirus is supported by demonstration of reverse transcriptase activity in the plasma and within the supernatant from primary kidney cell cultures of affected snakes.

Major histologic lesions include a nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis with neuronal degeneration, gliosis, and demyelinization. Intracytoplasmic inclusions are noted within degenerating neurons of the gray matter and ependymal cells. Inflammation in the central nervous system is more severe in pythons; however, intracytoplasmic inclusions are more numerous in boa constrictors. In the experience of pathologists at the National Zoological Park, Washington D.C., inclusion body disease has been found not only as a primary disease but also in association with secondary infections or as an incidental finding. In fact, many lesions within visceral organs of affected snakes have been attributed to secondary infections.

Contributor: Dept of Veterinary Pathology, Microbiology & Immunology School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA 95616.

Reference:

Schumacher J, Jacobson ER, Homer BL, Gaskin JM. Inclusion body

disease in boid snakes, J Zoo and Wildlife Med 25(4):511-24, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: None

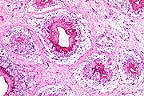

Numerous well-demarcated granulomas

in the subcutis of the neck of an emu. (HE, 100X, 64K)

Numerous well-demarcated granulomas

in the subcutis of the neck of an emu. (HE, 100X, 64K)

Signalment: Adult, female emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

History: A slowly growing mass was removed from the neck.

Gross Pathology: An ovoid mass with a slight yellow color submitted in 10% buffered neutral formalin.

Laboratory Results: N/A

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Xanthoma, lobular.

The section consisted of multiple lobular structures. Dense to myxomatous connective tissue separated individual lobules. A loose lipid and vacuolated reticular fibrinous material within which were numerous multinucleated giant cells and occasional macrophages formed the periphery of lobules. Forming zones within lobules were polygonal to ovoid macrophages, most with vacuolated or membrane-bound lipid droplets. Eosinophilic amorphous necrotic follicles and epithelial-like central ribbons with empty interiors usually overlay "foamy" macrophage accumulations.

This xanthoma occurred as a discrete mass. Some avian xanthomas present as diffuse thickening of the skin. Most consist of foam cells with occasional cholesterol clefts. In this case, the distinctive membrane-bound fat droplets within macrophages and the abundance of multinucleated giant cells suggest that lipid metabolism defects can stimulate diverse cell types. Xanthomatosis (diffuse skin thickening) in chickens has been believed caused by hydrocarbons in the feed. Some xanthomas may be congenial or genetically related to abnormal lipid metabolism. Others may be idiopathic or secondary to underlying dyslipoproteinemia.

AFIP Diagnosis: Subcutaneous tissue, neck (per contributor): Granulomas, multiple, with intrahistiocytic lipid, emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), ratite, avian.

Conference Note: Although careful consideration was given to the contributors diagnosis of xanthoma, the above diagnosis was preferred by the conference participants. As the contributor noted, avian xanthomas typically consist of "foam cells" often interspersed with cholesterol clefts. This case differs in that the lesion consists of well-formed granulomas with central necrotic cellular debris; lipid-type vacuoles are present in many of the macrophages. Similar lesions have been described in domestic fowl that were injected with oil adjuvant vaccines. Emus and ostriches are frequently given injections in the subcutaneous tissue of the lower neck. Gram's and acid fast stains and the GMS method did not demonstrate bacteria or fungi in the granulomas.

Contributor: Murray State Univ. - Breathitt Veterinary Center P.O. Box 200, 715 North Drive, Hopkinsville, KY 42241-2000.

References:

1. Gross, TL, Ihrke PH, Walder EJ: Veterinary Dermatopathology,

Mosby year Book, St. Louis, pp. 193-195, 1992.

2. Hulland TJ; Muscles and Tendons. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, Jubb KV, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds. 3rd ed., Academic Press, Inc., New York, Vol 1, pp. 162, 1993.

3. Jones TC, Hunt RD: Veterinary Pathology, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 1098-1132, 1279, 1983.

4. Petrak, ML, Gilmore CE: Neoplasms. In: Diseases of Cage and Aviary Birds, Petrak ML, ed., Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 610-611, 1982.

5. Riddell c: Developmental, Metabolic and Miscellaneous Disorders. In: Diseases of Poultry, Calnek BW, ed., 9th ed., Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA, pp. 855, 1991.

6. Randall CJ, Reece RLL: Color Atlas of Avian Histopathology, Mosby-Wolfe, pp. 42-43, 1996.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #4533, 11168.

Signalment: Adult female cynomolgus monkey.

History: This was a spontaneous lesion in a terminal sacrifice animal on a six month intravenous toxicity study. Two TB tests performed by the supplier and one test done at the test facility were all negative.

Gross Pathology: The right caudal lung lobe contained a single 0.5 cm diameter mass. The mass was tan, firm and exuded a tan creamy semifluid material when incised.

Laboratory Results: N/A

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Lung, focal granulomatous pneumonia with caseous necrosis and multinucleated giant cells. Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

An acid fast stain of the granulomatous focus in the lung showed acid-fast bacilli consistent with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Even though this animal had three consecutive negative TB tests and no known positive test, it still had a focal, active TB lesion in the lung.

AFIP Diagnosis: Lung: Bronchopneumonia, granulomatous, multifocal, moderate, with caseous necrosis and mineralization.

Conference Note: Tuberculosis is one of the most serious and economically devastating diseases of nonhuman primates; it is primarily encountered in captive primates, and is rarely seen in the wild. Old World monkeys are generally more susceptible to tuberculosis than are New World monkeys. The rhesus monkey appears to be the most susceptible, while the cynomolgus seems to be somewhat resistant. Tuberculin testing is not as reliable in cynomolgus macaques as it is in other primates. The route of infection may be cutaneous or via the alimentary or respiratory tract. In the respiratory form, variable numbers of tubercles are present within the lung, and there is often marked enlargement and caseation of bronchial lymph nodes. In advanced pulmonary tuberculosis, there may be a secondary intestinal infection due to swallowing coughed up sputum. Immunosuppressed animals often do not develop tubercles, but instead develop disseminated disease with a diffuse granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate similar to that found in Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infections.

The pathogenicity and virulence of mycobacteria depend on their ability to escape phagocytic killing mechanisms. This is mostly imparted by cell wall constituents and other products including:

The wax of the cell wall, peptidoglycans, and other glycolipids are responsible for the adjuvant activity of mycobacteria which includes attraction of antigen-presenting cells (macrophages) and presentation of antigen in appropriate configuration. Tubuloprotein is another important immunoreactive substance produced by mycobacteria. Tubuloproteins provide most of the antigenic determinants; however, the adjuvant activity provided by the cell wall materials is essential to development of an immune response. Purified tubuloproteins are capable of stimulating delayed hypersensitivity once the animal is sensitized; this is the basis of tuberculin testing.

Contributor: Corning Hazleton, 2201 Kinsman Boulevard, Madison, WI 53707.

References:

1. Benirschke K et al. Pathology of Laboratory Animals, Vol II.,

Spring and Verlag, NY, NY, pp. 1418-1421, 1978.

2. Hines ME et al. Mycobacterial Infections of Animals: Pathology and Pathogenesis, Lab An Sci 45(4), pp. 334-347, 1995

3. Cotran RS et al. Robbins: Pathologic Basis of Disease, 5th ed., Saunders, pp. 324-5, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #11613, 11616, 13132, 13147, 13148, 19521.

K. Lance Batey

Captain, VC, USA

Registry of Veterinary Pathology*

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

(202)782-2615; DSN: 662-2615

Internet: batey@email.afip.osd.mil

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.