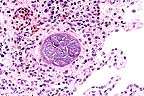

Dermal eosinophilic granuloma

with cross sections of Habronema remnants from the pastern

of a horse. (HE, 100X, 81K)

Dermal eosinophilic granuloma

with cross sections of Habronema remnants from the pastern

of a horse. (HE, 100X, 81K)Signalment: 3-year-old Pasofino stallion.

History: This animal had proliferative, ulcerative dermal changes associated with the left shoulder, withers and right pastern. Similar changes were noted adjacent to the urethral process. The pastern lesion was debulked and submitted for histopathology.

Gross Pathology: A single, domed-shaped piece of skin, measuring 8.0 x 6.0 x 4.0 cm had ulceration and fistulous tracts that extended into the adjacent subcutis. The cut-surface of the tissue varied from white to yellow.

Laboratory Results: Multiple bacterial species, but no fungi were isolated from the skin lesion.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Dermatitis, eosinophilic, granulomatous, ulcerative, fibrosing, locally extensive, severe with intralesional necrotic Habronema sp. larvae, skin of pastern.

Differential diagnosis also should include neoplasia such as sarcoid or squamous cell carcinoma as well as exuberant granulation tissue, fungal infection, and pythiosis. Cutaneous habronemiasis is induced by larvae of H. muscae, H. microstoma or Draschia megastoma at cutaneous and mucocutaneous sites. The larvae are transmitted to these sites by flies. Traditional sites for dermal reactions to occur are the ocular conjunctiva and the prepuce of the stallion. Histologically, aggregates of eosinophils, epithelioid macrophages and foreign-body giant cells typically react to the presence of Habronema larvae. Larvae or their remnants may be found embedded in some inflammatory reactions.

AFIP Diagnosis: Haired skin: Dermatitis, proliferative, eosinophilic, chronic, diffuse, severe, with eosinophilic granulomas, ulceration, epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and numerous larval nematodes, Pasofino, equine.

Conference Note: Draschia megastoma, Habronema majus, and H. muscae are spirurid nematodes that parasitize the stomach of horses. The Habronema sp. lie on the mucosal surface of the stomach, while Draschia megastoma burrows into the gastric submucosa and produces large eosinophilic granulomas. These spirurid parasites utilize flies as intermediate hosts; therefore, cutaneous lesions occur predominantly in the summer months when the intermediate host flies are present. Habronema larvae in horse feces are ingested by maggots of Stomoxys calcitrans (the stable fly) in the case of H. majus or muscuid flies (house flies) for the remaining two. The larvae persist through pupation and maturation of the flies. Horses become infected when the flies deposit larvae from their proboscises onto moist skin surfaces, such as the lips, or if horses ingest infected flies.

Cutaneous lesions occur in areas that attract flies such as the medial canthus of the eye, the glans penis, and prepuce, and cutaneous wounds. Grossly, the lesions appear as ulcerated proliferations of granulation tissue. They are friable and hemorrhage easily. Conjunctival lesions rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter; involvement of the lacrimal duct produces a characteristic lesion 2-3 cm below the medial canthus. Substantial involvement of the conjunctiva can result in marked lacrimation, photophobia, and chemosis. Lesions around the prepuce or penis often cause prolapse of the urethral process and dysuria.

Histologically, lesions consist of a highly vascular granulation tissue with neutrophils and other inflammatory cells at the periphery and central aggregates of eosinophils. If larvae or larval remnants are present, they are surrounded by epithelioid macrophages, multinucleate giant cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (eosinophilic granulomas).

Differential diagnosis for habronemiasis includes exuberant granulation tissue, botryomycosis, pythiosis, equine sarcoid, and squamous cell carcinoma. Habronema has also been reported as a secondary infection of cutaneous lesions induced by pythiosis, Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Contributor: Dept. Of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Box 100103, Gainesville, FL 32610.

References:

1. 1. J.R. Vasey: Equine cutaneous habronemiasis. Comp. Cont.

Ed. 3:p.290-295, 1981.

2. A.J. Trees, S.A. May and J.B. Baker: Apparent case of equine cutaneous habronemiasis. Vet. Rec.115:14-15,1984.

3. Yager JA, and Scott DW: The skin and appendages in Pathology of domestic animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N, eds., Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, 4th edition, volume 1, pp. 692-693.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #318, 937, 1400, 1808, 1995, 2740, 4371-2, 7412, 9328, 12817, 13701, and 18815.

Signalment: 4-year-old male Labrador Retriever dog.

History: Acute respiratory distress, cyanosis of the tongue, convulsions and status epilepticus. Petechial hemorrhages were seen on the skin. The dog died after a few hours of illness.

Gross Pathology: Cranioventral regions of both lungs were enlarged, dark red, firm and did not float in water. Multifocal hemorrhagic lesions were also seen in caudal lobes. Petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages were present on serosal surfaces and in subcutaneous tissues.

Laboratory Results: A heavy growth of non-hemolytic Escherichia coli was obtained from the lungs.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Severe hemorrhagic pneumonia. Cause: Escherichia coli.

There are diffuse hemorrhages within the alveoli. Large numbers of small gram-negative rods are present free in the alveolar hemorrhagic fluids and within the cytoplasm of large foamy macrophages. Focal accumulation of these large foamy macrophages and few neutrophils are observed within alveoli. Lesions were not observed in the intestines and lymphoid organs.

These microscopic lesions are typical of the hemorrhagic pneumonia caused by E. coli in dogs. This is a fulminating disease causing sudden deaths, particularly in young dogs.

These lesions can appear as a cranioventral bronchopneumonia or, more frequently, as a focal pneumonia. The pathogenesis of this condition is unknown. Lung lesions caused by E. coli septicemia and endotoxemia have been reported in dogs with fatal canine parvovirus infections. These lesions were apparently not as severe as those seen in this dog. We have been able to associate some of these cases of E. coli hemorrhagic pneumonia with clinical or subclinical parvovirus infections. In several other cases, this association could not be made.

AFIP Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, hemorrhagic, acute, diffuse, severe, with numerous intrahistiocytic and extracellular bacilli, Labrador Retriever, canine.

Conference Note: The pulmonary effects of bacterial lipopolysaccarides (LPS; endotoxin) are primarily mediated by vascular damage. Bacterial lipopolysaccrides are directly toxic for endothelial cells and indirectly affect endothelial cells via stimulation of macrophage/monocyte populations to secrete proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 1 (IL-1).

Endotoxemia results in endothelial cell loss and exposure of the underlying basement membrane. The exposure of basement membrane collagen activates the intrinsic coagulation cascade. Recent studies have demonstrated that E. coli and Pasteurella haemolytica lipopolysaccharides also increase tissue factor (thromboplastin; factor III) activity in endothelial cells. The expression of tissue factor on endothelial cells is capable of initiating the extrinsic coagulation cascade. Tissue factor acts as a cofactor for factor VII. The factor VII and tissue factor complex, in concert with calcium and phospholipid, activates factor X, resulting in formation of thrombin and eventually, fibrin production.

Macrophages and monocytes are very sensitive to endotoxins and respond by secreting IL-1, TNF and other cytokines. Endothelial cells treated with IL-1 or TNF have increased tissue factor activity and increased tissue plasminogen activator production. In addition, LPS diminishes anticoagulative properties of endothelial cells by reducing or inactivating thrombomodulin or tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor. The result of these proinflammatory cytokine influences on endothelial cells is a procoagulative state and interruption of coagulation homeostasis.

The results of endotoxin damage to pulmonary endothelial cells and disruption of coagulation homeostasis are edema, hemorrhage, hyaline membranes, and thrombosis. A similar pathogenesis is proposed for fibrinohemorrhagic pneumonia in cattle caused by Pasteurella haemolytica and some forms of adult respiratory distress syndrome in humans.

Contributor: Department of Pathology and Microbiology Fac. Of Veterinary Medicine, University of Montreal, P.O. Box 5000, St. Hyacinthe, Quebec Canada, J2s-7C6.

References:

1. Turk, J et al. Coliform septicemia and pulmonary disease associated

with canine parvoviral enteritis: 88 cases (1987-1988). JAVMA

196: 771-773. 1990.

2. Breider MA and Yang Z: Tissue Factor Expression in Bovine Endothelial Cells Induced by Pasteurella haemolytica Lipopolysaccharide and Interleukin-1. Vet Pathol 31:55-60, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #3929, and 23035.

Signalment: Term fetus, female Dorset ovine.

Septic and necrotizing placentitis

due to Salmonella arizona in a sheep. (HE, 400X, 54K).

Septic and necrotizing placentitis

due to Salmonella arizona in a sheep. (HE, 400X, 54K).

History: This was the 2nd full-term fetus to die at lambing. The fetus was not in the birth canal but the ewe was in labor. Labor began mid-afternoon and the lamb was pulled with difficulty at 6 PM. The ewe was not clinically sick after losing the lamb. The 25 ewes in this group were in loose housing with access to grass/legume pasture and grain supplementation.

Gross Pathology: Crown-rump length of the female fetus was 48 cm. There was a light fibrin coating of the lungs.

Laboratory Results: Large numbers of Salmonella arizonae were isolated from fetal lung, stomach contents, and spleen, as well as from placenta. Chlamydia was not isolated (yolk sac inoculation).

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Lesions were restricted to lung (moderate alveolitis) and placenta (severe necrotizing placentitis with large numbers of Salmonella organisms in trophoblasts and placental blood vessels); due to Salmonella arizonae.

The presence of massive numbers of organisms in trophoblasts in an ovine placenta is highly suggestive of Coxiella infection. However, Coxiella is typically restricted to the trophoblasts and does not invade deeper placental tissues. Further query of the owner revealed that the sheep were housed in a barn that formerly housed turkeys, a possible source of the Salmonella. Salmonella arizonae can be recovered from the small and/or large intestine of sheep in the absence of intestinal lesions (1), and these sheep may have been carriers of the organism.

AFIP Diagnosis: Placenta: Placentitis, necrotizing, subacute, diffuse, moderate, with vasculitis, and colonies of coccobacilli, Dorset, ovine.

Conference Note: Salmonella is an important cause of abortion in cattle and sheep. The organism may be carried by the host without clinical disease and is excreted in the saliva, milk, feces, urine, and in fluids discharged at abortion. Animals can become infected through feed, water, or bedding.

The proposed pathogenesis of placental infection by Salmonella begins with an enteric infection followed by bacteremia and localization in lymph nodes, spleen, and lung. A second bacteremia occurs and results in infection of the placentome. Bacterial growth causes destruction of the fetal villi and abortion of an autolyzed fetus. The placenta is often retained after abortion.

Grossly, the chorioallantois is thickened by amber, fibrin-containing fluid. Portions of the caruncle may remain adherent to the cotyledon. Histologically, there is mineralization of the trophoblast cells, interstitium of the villi, and chorioallantoic arcade. The villi are often expanded by large numbers of Salmonella, and, in some villi, neutrophils. Dilated capillaries, immediately under the sloughed trophoblast cells in the arcade zone, are expanded by bacteria and resemble large rounded trophoblast cells filled with bacteria. The fetus is often free of lesions; however, bacteria may occasionally be found colonizing the airway epithelium. Suppurative hepatitis has also been reported in fetuses from Salmonella-induced abortions.

Contributor: Ontario Ministry of Agriculture & Food Veterinary Laboratory Services, Box 3612, Guelph, Ontario, H1H-6R8.

References:

1. Lang JR, Finley GG, Clark MH, Rehmtulla AJ: Ovine fetal infection

due to Salmonella arizonae, Can. Vet. J. 1978;19:260-263.

2. Kennedy PC, and Miller RB: The Female Genital System in Pathology of Domestic Animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N eds., Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, 4th edition, Vol. 3, pp. 410-411, 1993.

Signalment: 1-month-old male southern whistling heron (Syrigma sibilatrix sibalitrix).

Megaloschizont of Leukocytozoon

in the lung of a whistling heron. (HE, 200X, 65K)

Megaloschizont of Leukocytozoon

in the lung of a whistling heron. (HE, 200X, 65K)

History: Found dead in nest.

Gross Pathology:

1. Hepatosplenomegaly. 2. Intraluminal hemorrhage - intestine.

Laboratory Results: Aerobic bacterial cultures of spleen were negative.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Severe diffuse subacute and granulomatous pneumonia with multifocal megaloschizonts and multifocal acute hemorrhage - lung. Etiology: Leukocytozoon sp.

Megaloschizonts also are present in many other tissues (heart, skeletal muscle, proventriculus, skin, spleen, kidney, adrenal gland, thyroid gland, peripheral nerve, intestine, bursa of Fabricius, pancreas). Inflammation is not associated with the megaloschizonts.

Leukocytozoonosis has been described in more than 100 species of birds. At our institution, sporadic cases of leukocytozoonosis have been seen in several species of birds. Typically, megaloschizonts are not associated with inflammation. In this case, there is some question as to whether the pneumonia is the result of ruptured Leucocytozoon megaloschizonts, or if other causes of pneumonia may be involved. Gram and GMS stains of lung are negative for organisms.

AFIP Diagnosis: Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with hemorrhage and megaloschizonts, southern whistling heron (Syrigma sibilatrix sibilatrix), avian.

Conference Note: Leucocytozoon (family Plasmodiidae) is a protozoan parasite of birds. There are over 70 species, the most common being L. simondii in ducks and geese, L. smithi in turkeys, L. caulleryi in chickens, and L. lovati and L. toddi in grouse and hawks. Leucocytozoon are pathogenic for anseriforms, galliforms, some passeriforms, and to a lesser degree, psittacines.

Simulium spp. (black flies) and Culicoides spp. (midges) are vectors of Leucocytozoon. Sporozoites in the salivary glands of insects enter the circulation of birds when the insects bite. First generation schizonts develop in hepatocytes and endothelial cells and, when mature, release thousands of merozoites. These merozoites are believed to initiate a second generation in hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and phagocytic cells forming large megaloschizonts. Other merozoites enter erythrocytes and leukocytes where they develop into gametocytes. The gametocytes are pale, fusiform, 14-22 x 4-6 æm structures found in distorted host cells that have compressed, thin, dark nuclei along the sides of the gametes. Sporogony occurs in the digestive tract of the fly. Oocysts form in the insect's stomach and release sporozoites when mature. These sporozoites migrate to the salivary glands to complete the cycle.

The principle clinical effect of Leucocytozoon infection is an intravascular hemolytic anemia, a result of both the mechanical destruction of erythrocytes by the protozoa and protozoal production of an antierythrocytic factor. Gross lesions include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and pericardial effusion. Megaloschizonts appear as grey-white nodules in the heart, liver, lung, or spleen. Histologically, there is ischemic necrosis and associated inflammation in the heart, brain, spleen, and liver due to occulsion of blood vessels by megaloschizonts in endothelial cells. In addition, ruptured schizonts may induce granulomatous reactions in the surrounding tissues.

Contributor: Dept. of Pathology, San Diego Zoo, P.O. Box 551, San Diego, CA 92112-0551.

References:

1. Leukocytozoon: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissue,

C.H. Gardiner, R. Fayer, J.P. Duby. USDA Agriculture handbook

#651 (1988) p.72.

2. Greiner EC and Ritchie BW: Parasites in Avian Medicine: Principles and Application. Ritchie BW, Harrison GJ, and Harrison LR, eds., Wingers Publishing, Inc., Florida, pp. 1020, 1994.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #31, 11096, 11206, 12671-2, and 23250.

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.