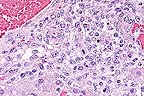

Lymphohistocytic hepatitis

in an aborted foal. Note the eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion

bodies within several degenerate hepatocytes. (HE, 400X, 75K)

Lymphohistocytic hepatitis

in an aborted foal. Note the eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion

bodies within several degenerate hepatocytes. (HE, 400X, 75K)Signalment: 290-day gestational age foal.

History: Four of fifteen mares housed together in Hagerman, Idaho, aborted over a thirty day period. Premonitory signs were not seen in any mares prior to abortion.

Gross Pathology: Foal tissues were icteric. The placenta and proximal umbilicus were thickened with clear gelatinous material (edema).

Laboratory Results: Equine herpesvirus-1 was isolated from the placenta and a pooled tissue sample containing liver, kidney, and lung. Immunohistochemical stains were done using in-house, polyclonal, rabbit, anti-equine herpesvirus-1 antisera followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit sera and avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA).

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Hepatitis, granulomatous, periportal, moderate, with rare random foci of hepatocellular necrosis and associated intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies.

Equine herpesvirus-1 is an important cause of abortion in mares in addition to producing neurologic disease. Characteristic lesions in aborted foals are seen in the lung (necrosis of bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, fibrinous alveolar exudation), liver (multifocal hepatocellular necrosis, periportal hepatitis), and lymphoid tissues (necrosis of germinal centers).ý Intranuclear inclusion bodies are seen in bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, hepatocytes, and fixed and infiltrated macrophages. In this case, necrosis with accompanying inclusion bodies were seen in the liver, spleen, thymus, lung, and adrenal glands. In liver sections, intranuclear inclusions were most common in hepatocytes bordering necrotic foci and in infiltrated macrophages.

Etiologic diagnosis was made by immunohistochemical staining and verified by viral culture.

AFIP Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, acute, multifocal, random, moderate, with lymphohistiocytic perivascular inflammation, and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies, thoroughbred, equine.

Conference Note: Equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) is an alphaherpesvirus that has a worldwide distribution, causing abortion, pneumonia, and neurologic disease. Most foals are exposed to EHV-1 before they reach one year of age. In most cases, a mild to severe respiratory disease ensues that is occasionally complicated by secondary bacterial infection. The level of immunity developed against EHV-1 is low and primary exposure to the virus does not protect from reinfection or recrudescence of latent virus later in life.

Mares that abort seldom show premonitory signs and the fetus is aborted in a fresh state; 95% of abortions occur in the last 3 months of gestation. The aborted fetuses often have subcutaneous edema and effusions in body cavities. The most consistent gross lesion is severe pulmonary edema. The lungs, renal cortices, and liver frequently have multifocal areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Histologically, there is edema, hemorrhage, and necrosis multifocally throughout the lung and liver. Necrosis of germinal centers in the spleen, thymus, and lymph node is common. Intranuclear inclusions can be found in respiratory epithelium, hepatocytes, and cells of the monocyte-macrophage system. The placenta is normal in alphaherpesviral abortions.

Other equine herpesviruses include equine herpesvirus-3, the cause of equine coital exanthema, and equine herpesvirus-4. Equine herpesvirus-4 (rhinopneumonitis virus) also causes respiratory disease and abortion; however, it is more frequently associated with respiratory disease and less commonly with abortion.

Contributor: Dept. Of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-7040.

References:

1. Schultheiss, P.C., Collins, J.K., and Carmen, J. 1993. Use

of an immunoperoxidase technique to detect equine herpesvirus-1

antigen in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded equine featal tissues.

Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 5:12-15.

2. Campbell, T.M., and Studdert, M.J. 1983. Equine herpesvirus type1 (EHV1). Veterinary Bulletin 53:135-146.

3. Jonsson, L., Breck-Friis, J., Renstrom, L.H.M., Nikkila, T., Thebo, P., and Sundquist, B. 1989. Equine herpes Virus 1 (EHV-1) in liver, spleen, and lung as demonstrated by immunohistology and electron microscopy. ACTA Veterinaria Scandinavica 30:141-146.

4. Kennedy PC and Miller RB: The female genital system in Pathology of domestic animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N eds., Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, pp. 437-438, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #6794, 7673, 13127, 13844-7, 13857, and 18401.

Signalment: 3 to 4-month-old crossbred neutered male pig.

History: This is one of a group of pigs kept in an outdoor pen. Most pigs had been passing loose stool that contained blood and mucus. The pigs were dewormed 1 week prior to the euthanasia and necropsy of this pig.

Gross Pathology: The mucosa of the cecum and proximal colon was covered by large numbers of adherent Trichuris suis. There were erosions and hemorrhages of the superficial mucosa. Blood was mixed with the intestinal contents.

Laboratory Results: Frozen sections of large intestine were negative for Serpulina hyodysenteriae by florescent antibody staining. Spirochetes were not found in smears prepared from mucosal scrapings. Serogroup B Salmonella sp. was isolated from the colon.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments:

1. Colitis, erosive, superficial, purulent, multifocal with nematodes compatible with Trichuris suis.

2. Colitis, purulent, deep, multifocal-coalescing, chronic.

Etiology: 1. Trichuris suis 2. Serogroup B Salmonella sp.

Trichuris suis is an important cause of diarrhea and poor growth in pigs raised in dirt lots. When infection is heavy, the fecal material often contains blood and mucus and there are erosions and hemorrhages in the cecum and proximal colon. As they are in this case, the nematodes are closely associated with or embedded into the colonic mucosa. In these sections, there are many foci in which the superficial mucosa is eroded and there is migration of neutrophils into the colonic lumen. Balantidium coli are often present in association with the T. suis and the crypts are filled with mucus. These changes, without the nematodes, are also seen with swine dysentery caused by Serpulina hyodysenteriae. We did not find any nematodes that contained the characteristic bipolar ova, indicating that the infection was probably not patent. In addition to the superficial colitis, most colon sections contain dilated crypts that are prolapsed into the submucosa and filled with neutrophils and mucus. In the submucosa there are multiple, coalescing infiltrates of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. This submucosal inflammation is indicative of infection by an invasive organism and is compatible with the group B Salmonella sp. that was isolated.

AFIP Diagnosis: Cecum and colon (per contributor): Typhlocolitis, subacute, diffuse, moderate, with erosions, glandular herniation and abscessation, adult trichurid nematodes, and Balantidium coli, cross breed, porcine.

Conference Note: Trichuris sp., or whipworms, inhabit the cecum and occasionally the colon of all domestic animals except the horse. The life cycle is direct and eggs can persist in the environment for several years. Ingestion of larvated eggs leads to release of third-stage larvae which enter the mucosa of the small intestine for 7-10 days before they reenter the gut lumen and move to the cecum. There is a prepatent period that lasts from 6-12 weeks depending upon the species. Infection is usually light and there is little alteration of the mucosa. Mucohemorrhagic typhlocolitis may develop in heavy infections and is characterized by mucus hypersecretion from hypertrophied colonic glands, focal hemorrhage, erosions, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate within the lamina propria. The following are characteristic histologic features of trichurids: a stichosome, a bacillary band at the anterior end, and hypodermal bands within the musculature rather than the lateral hypodermal chords seen in other families of nematodes.

Balantidium coli is a large ciliated protozoan with both a macronucleus and micronucleus. It is a commensal parasite in the cecum and colon of swine but often complicates necrotizing or ulcerative diseases of the cecum and colon, especially trichurid infection, intestinal adenomatosis, swine dysentery, and salmonellosis.

In swine, salmonellosis usually occurs in 2 to 4-month-old feeder pigs. There are three syndromes associated with salmonellosis in swine: a septicemic disease associated with S. cholerasuis, enterocolitis and necrotizing proctitis associated with S. typhimurium, and caseous tonsillitis, lymphadenitis, and ulcerative colitis associated with S. typhisuis.

Salmonella cholerasuis causes a septicemic disease that induces endothelial damage due to endotoxemia and localization of bacteria. Characteristic lesions include hemorrhage in lymph nodes, laryngeal mucosa, spleen, liver, and intestine. In chronic cases, the intestine is often affected and presents as a hemorrhagic enteritis and/or fibrinohemorrhagic colitis with button ulcers. Small areas of coagulative necrosis form in the liver which are then surrounded by macrophages and lymphocytes as the lesion progresses; these hepatic lesions are referred to as paratyphoid nodules. There is often an interstitial pneumonia due to endotoxemia and embolic bacteria. Meningoencephalomyelitis often occurs as a result of vasculitis and bacterial emboli.

Salmonella typhimurium causes chronic and intermittent diarrhea. Lesions are confined to the colon, cecum, and rectum. There is an acute enterocolitis with a pseudodiphtheritic membrane on the mucosal surface. The ulcerative proctitis associated with S. typhimurium is believed to induce cicatrization and stricture of the rectum resulting in megacolon.

Salmonella typhisuis causes focal to confluent ulceration of the ileum, cecum, colon, and rectum. Additionally, it causes massive enlargement of the neck due to caseous palatine tonsillitis, cervical lymphadenitis, and parotid sialoadentits.

Contributor: Kansas State University, Department of Diagnostic Laboratory, college of Veterinary Medicine, VCS Bldg. Rm L-208, Manhattan, KS 66506.

References:

1. Corwin RM, Stewart TB. Trichuris suis. In: Leman AD, Straw

BE, Mengeling WL, et al., eds. Diseases of Swine 7th ed, Iowa

State University Press: Ames, IA, 1992;726.

2. Barker IK, Dreumel AA van, Palmer N. Trichuris infection. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds., Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed, Academic Press Inc: New York, 1993;277-279.

3. Barker IK, Dreumel AA van, Palmer N. Salmonellosis in swine. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds., Pathology of Domestic Animals, 4th ed, Academic Press Inc: new York, 1993;217-221.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #(Trichuris)3630, 8826, 8950, 3941, 10146, and 20481-2. (Salmonellosis)#5337, 8887, 8936-7, 9044-6, 9532-3, 10150-1, 13130, 13549, 18901, 23104-5, and 23172.

Signalment: Two and one half-week-old female Hereford calf.

History: The calf was orphaned at one and one half weeks of age. She was presented to the hospital emaciated and depressed and would not suckle. After some improvement the calf developed a fever and deteriorated and was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The rumen contained milk, corn and hay. Both the rumen and reticulum had marked proliferation of the mucosa with hyperkeratosis producing a corrugated surface. Ulcers were present on the rumen pillars and scattered through the rumen and reticulum.

Laboratory Results: None.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Rumen: rumenitis, proliferative, vesiculopustular, diffuse, severe, bovine.

Microscopically, this rumen has epithelial hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis. The epithelium is edematous with vesicle formation, and a purulent inflammation is present with the formation of pustules. Large numbers of bacilli are on the lumenal surface along with a few yeast organisms consistent with Candida sp.

This lesion is typical of that produced in lactic acidosis due to grain overload. In this calf on a milk diet the lesion is caused by excessive milk entering the rumen and producing lactic acidosis. This can be caused by consumption of excessive amounts of milk, reticular groove dysfunction, or tube feeding of milk. The disease is not usually fatal but can result in weight loss and poor condition. This calf may have developed a secondary infection/septicemia which resulted in death.

AFIP Diagnosis: Rumen: Rumenitis, necrosuppurative, diffuse, moderate, with epithelial hyperplasia, and intracellular edema, Hereford, bovine.

Conference Note: The normal rumen is anaerobic with a pH of 6.5 and a microflora of gram-negative bacteria and protozoa that produce the volatile fatty acids; acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. Ingestion of easily fermentable carbohydrates causes an increase in total volatile fatty acids and lowers the rumen pH. As the pH drops, normal flora are replaced by Streptococcus bovis which produces lactic, formic, valeric, and succinic acids. At a pH less than 4.5, S. bovis is inhibited and there is an overgrowth of Lactobacillus, which produces large quantities of lactic acid, further reducing rumen pH. The rumen contains epithelial receptors that are activated by lactic, propionic, and butyric acid. Activation of these receptors cause a decrease in ruminal motility. The increase in volatile fatty acids also raises the osmotic pressure in the rumen, and there is movement of fluids from the vascular spaces into the rumen resulting in hemoconcentration, anuria, and hypotension. A systemic acidosis occurs as lactic acid is absorbed from the rumen. If the acidosis is uncompensated, death occurs due to decreased tissue perfusion, decreased cardiac output, and metabolic acidosis.

Histologic changes in ruminal acidosis are probably induced by the chemical environment and are characterized by vacuolation of epithelial cells (often leading to vesiculation), neutrophilic infiltration of the mucosa and submucosa, and mucosal erosions or ulceration.

Frequently, the damaged rumen is secondarily infected by Fusobacterium necrophorum or fungi. Other complications of rumenitis include laminitis and an encephalopathy which resembles polioencephalomalacia (this is probably caused by a decrease in thiamine producing bacteria).

Contributor: Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061-0442.

References:

1. OM Radostits, DC Blood, CC Gay (eds). Veterinary Medicine,

8th ed. Balliere Tindall, London, pp. 261-262, 1994.

2. Barker IK, Van Dreumel AA, and Palmer N: The Alimentary System in Pathology of Domestic Animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, and Palmer N, eds. , Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Vol 2, pp. 47-50, 1993.

3. Rumen lactic acidosis, part I. Epidemiology and pathophysiology. Comp Cont Ed, 14(8):1127-113, 1992.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #385, 401-4, 2667, 2820, 3959-60, 4046, 4088, 5652, 18959, 19000-1, 20182-4, 21170, 22240, and 22246.

Signalment: Ten-year-old Holstein cow.

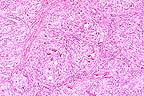

Renal cell carcinoma in a

cow. (HE, 200X, 80K)

Renal cell carcinoma in a

cow. (HE, 200X, 80K)

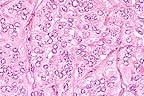

Higher

magnification of field above showing charcteristic tubule formation.

(HE, 400X, 60K)

Higher

magnification of field above showing charcteristic tubule formation.

(HE, 400X, 60K)

History: Normal antemortem.

Gross Pathology: Bilateral and multifocal 1-20 cm masses in both kidneys. The masses are within the renal cortex, light yellow, and well circumscribed. No other lesions were found.

Laboratory Results: None submitted.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Renal cell tumor, eosinophilic granular cell type.

The 1 cm renal mass is well circumscribed and partially encapsulated. The mass elevates the renal capsule and extends almost to the corticomedullary junction. The tumor is subdivided into lobules by a dense fibrovascular stroma. Foci of lymphocytes and plasma cells, hemorrhage and hemosiderin are scattered in adjacent renal interstitial tissue. The tumor is composed of cuboidal to columnar cells forming papillary, cystic, and tubular areas as well as scattered solid areas. Cells tend to be polygonal in solid areas. Tumor cells have oval to round nuclei with stippled chromatin. Nuclei are often located at the basilar end of the cell, especially when forming tubules or papillary structures. Mitotic figures are rare. The cells have eosinophilic finely granular cytoplasm with distinct cellular margins. Cystic spaces and tubules contain proteinaceous product and laminated calcified spherical concretions (corporea amylacea).

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Renal cell carcinoma, Holstein, bovine.

Conference Note: Renal cell carcinoma is the most common renal tumor of dogs, cattle, and sheep. It is most common in mature and aged animals. Polycythemia associated with erythropoietin production by the neoplasm occurs rarely and resolves when the mass is excised. Histologically, neoplastic cells are cuboidal to polygonal with distinct cell borders. The cytoplasm of neoplastic cells varies from eosinophilic or basophilic and granular to vacuolated and clear. Renal clear cells are present in variable numbers in most renal carcinomas, even when they are not the predominant cell type. Neoplastic cells can be arranged in sheets, papillary projections or tubular structures; all of these patterns may be present within a single tumor. Renal cell carcinomas grow expansivily and there is often local invasion. In the dog, metastasis is common and widespread, usually to the lung and liver. Metastasis is reported less frequently in cattle.

Known causes of renal carcinoma in animals include exposure to aflatoxins, estrogens, and lead. Additionally, viruses are an important cause of renal cell carcinoma in leopard frogs (Lucke' virus), chickens, and gray squirrels.

Contributor: USDA, FSIS, Eastern Lab, P.O. Box 6085, Athens, Georgia 30604.

References:

1. Kelley LC, Crowell WA, Puette M, Langheinrich KA, and Self AD: A Retrospective Study of Bovine renal cell tumors. Vet Pathol 33:133-141, 1996.

2. Maxie GM: The urinary system in Pathology of domestic animals. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N eds., Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, pp. 519-520, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #18455-8, and 23939.

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.