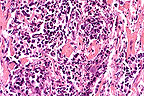

Suppurative and necrotizing

myocarditis with colonies of extracellular H. somnus bacilli

in a feedlot calf. (HE, 400X, 67K)

Suppurative and necrotizing

myocarditis with colonies of extracellular H. somnus bacilli

in a feedlot calf. (HE, 400X, 67K)Signalment: Cross-bred beef calf, 400 pounds.

History: A feedlot reported 3 of 450 calves to be found dead suddenly or exhibiting CNS signs.

Gross Pathology: The calf was posted in the field and tissues submitted by the local veterinarian. He noted chronic cranioventral pneumonia, ulcerative laryngitis and hemorrhages in brain and myocardium.

Laboratory Results: Hemophilus somnus was isolated from the lung and heart.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Myocarditis, purulent and necrotizing with septic infarction, acute, severe. Etiology: Hemophilus somnus. There were also lesions in the brain compatible with H. somnus-induced Thromboembolic meningoencephalitis (T.E.M.E.).

AFIP Diagnosis: Heart: Myocarditis, necrosuppurative, multifocal, moderate, with necrotizing vasculitis, fibrin thrombi, and intravascular and extravascular bacilli, cross breed, bovine.

Conference Note: Hemophilus somnus is a small gram-negative, pleomorphic coccobacillus that is a commensal organism of the bovine urogenital and respiratory tracts. In cattle, H. somnus causes a septicemia that predominantly affects immature cattle, causing acute death or localization in one or several organs. Affected cattle have usually been subjected to increased environmental stress, including weaning and shipping. The route of transmission and mechanism by which H. somnus invades the bloodstream are unknown; the organism is able to survive phagocytosis and readily replicate within bovine macrophages. Upon entering the vascular system, the bacteria adhere to endothelial cells causing them to contract and expose the subendothelial collagen. The exposed collagen initiates the intrinsic coagulation cascade, causing thrombosis. The presence of the bacteria also induces an inflammatory response that results in vasculitis. Vasculitis and thrombosis can develop in any organ but cerebral vessels are especially vulnerable; vasculitis and thrombosis of these vessels results in thrombotic meningoencephalitis, the most characteristic lesion of H. somnus infection.

In North America, localization of H. somnus in myocardium is common and results in vasculitis and myocardial infarction or myocardial abscessation. Myocardial abscesses are most common in the left ventricular free wall, particularly the papillary muscles. Death in these animals is usually caused by cardiac failure.

Other syndromes associated with H. somnus include bronchopneumonia, laryngeal ulceration, fluid distention of the joint capsules (especially the atlanto-occipital joint) and abortion.

Contributor: South Dakota State University, Dept. Of Veterinary Science, Brookings, SD 57007.

References:

Jubb, KVF; Kennedy, PC; Palmer, N: Pathology of Domestic Animals,

Vol 1 pp 245, 397-399, Vol 2 pp 84, 102, Vol 3 pp 28, 395, 413-414,

517, 521, Academic press, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #95, 3105-6, 5006-7, 5011, 7760, and 12715.

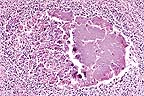

Signalment: 4-year-old male bison.

Colonies of Brucella abortus

in the testicle of a 4-year-old bison. (HE, 400X, 73K)

Colonies of Brucella abortus

in the testicle of a 4-year-old bison. (HE, 400X, 73K)

History: This bison bull was from the last captive herd of bison known to be infected with Brucella abortus. By routine serological evaluation, it remained free of brucellosis for three years but had strong positive responses at 4 years of age. In 1995, it developed serologic titers to brucella antigens. At slaughter, inspectors did not report finding gross lesions other than an enlarged testicle (roughly 2X normal).

Gross Pathology: Enlarged testicle, roughly 2X normal. The testicle had a central necrotic area with radiating regions of necrosis that variably extended from the necrotic center to the tunica albuginea. No other gross lesions were reported from this bull or 7 other bulls slaughtered.

Laboratory Results: Serum from the bull had high titers to Brucella abortus on the card, complement fixation and standard tube agglutination tests.

Pure colonies of Brucella abortus, biovar 1, were grown from testicular tissue. Brucella antigens were detected by immunocytochemistry in tissue sections.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Marked multifocal and extensive caseonecrotic orchitis with intralesional immunoreactivity for Brucella antigens. Etiology: Brucella abortus, biovar 1.

Brucellosis is relatively common and difficult to control in bison (Bison bison) and other wild ruminants such as elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni), reindeer, and caribou. In the United States, brucellosis of bison and elk occurs mainly in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho (the region known as the Greater Yellowstone Area). The disease does not prevent population growth of the two species but does pose a risk to the Cooperative Brucellosis Eradication Program. In this respect, infected wild bison and elk are a threat to other herds and cattle. Brucellosis in reindeer and caribou occurs in Alaska.

AFIP Diagnosis: Testis: Orchitis, pyogranulomatous, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with mineralization, fibrosis, and intrahistiocytic bacilli, American bison (Bison bison), bovid.

Conference Note: Brucella are small gram-negative coccobacilli that cause recurrent or chronic bacteremia and tend to localize and persist in the male and female reproductive tract, mammary glands, and associated lymph nodes. Transmission occurs by ingestion of infected secretions (milk or urine) or tissues, especially the placenta and abortus. The bacteria are phagocytized by neutrophils and macrophages; however, many survive within the phagolysome. Survival is believed to be mediated by a surface lipopolysaccharide, the O antigen, which inhibits fusion of the phagosome and lysosome. The bacteria initially replicate within the lymph nodes and then disseminate to peripheral tissues. The organisms localize in the lymph nodes, testes, and accessory sex glands of the male. Lesions initially develop in the cavity of the tunica vaginalis which becomes distended with fibrinopurulent exudate and hemorrhage. The infection spreads to the parenchyma of the testes, causing necrosis, and progresses through the seminiferous tubules. The lesion frequently progresses to total testicular necrosis. The inability of the tunica albuginea to stretch prevents swelling of the testes, causing pressure necrosis which compounds the tissue destruction. In addition, there is frequently an associated necrotizing epididymitis.

Brucella is best known for producing abortion. The presence of large amounts of erythritol (a 4-carbon alcohol) in the pregnant uterus is believed to contribute to the preferential colonization of this organ. Brucella utilizes erythritol in preference to glucose for energy production. The bacteria are phagocytized or penetrate trophoblasts in the placenta, replicate, and cause cellular death. The bacteria spread to the fetus via placental vessels, causing disseminated inflammatory reactions and thymic cortical lymphoid depletion.

Contributor: USDA/ARS National Animal Disease Center, P.O. Box 70, 2300 Dayton Road, Ames, Iowa 50010.

References:

1. Creech GT: Brucella abortus infection in a male bison. North

Am Vet 11:35, 1930.

2. Davis DS, Templeton TA, Ficht JD, William JD, Kopec JD, Adams LD: Brucella abortus in captive bison. I. Serology, bacteriology, pathogenesis, and transmission to cattle. J Wildl Dis 26:360-371, 1990.

3. Davis DS, Templeton TA, Ficht JD, Huber JD, Angus RD, Adams LGF: Brucella abortus in captive bison. II. Evaluation of strain 19 vaccination of pregnant cows. J Wildl Dis 27:258-264, 1991.

4. Thorne ET, Herriges Jr JD: Brucellosis, Wildlife and Conflicts in the Greater Yellowstone Area. Trans. 57th N. A. Wildl and Nat. Res. Conf. PP. 453-465, 1992.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank: Laser disc frame #79, 80, 126, 2080, 3016-17, 3062-64, 6933-39, 7365, and 7367.

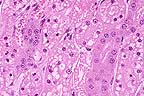

Signalment: 4-year-old spayed female Siamese - cross cat.

Acute tubular necrosis in

a cat that had ingested an Asiatic lily. (HE, 400X, 54K.)

Acute tubular necrosis in

a cat that had ingested an Asiatic lily. (HE, 400X, 54K.)

History: This house cat ate the entire bloom of an Asiatic lily that had been placed in a vase on the kitchen counter (Day 1). That evening the cat appeared to be "frightened". During the next two days (Days 2 and 3), it did not eat or drink and emesis was observed. On the evening of Day 3, it was presented to a veterinarian with ataxia, severe dehydration, apparent abdominal pain and seizures. Treatment included diazepam to control the seizures and intravenous fluids. Subsequent assessments revealed that despite the fluid therapy, there was no urine production (anuria). The cat became comatose approximately 3 hours after presentation and was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The thoracic and abdominal cavities contained approximately 25 cc of pale yellow fluid. The lungs were hyperemic and edematous and the kidneys were slightly swollen. No other abnormalities were identified.

Laboratory Results: Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)>140 mg/dl; glucose 108 mg/dl; alanine aminotransferase - 282 IU/L.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Morphologic diagnosis: Kidney, cortex: necrosis, tubular, diffuse, subacute, severe, with preservation of tubular basement membranes, tubular regeneration, and granular casts. Etiologic diagnosis: Nephrotoxic tubular necrosis (nephrosis). Etiology: Lily toxicosis.

This section of kidney is characterized by severe diffuse degeneration and necrosis of cortical tubules. Tubular basement membranes are preserved and lumina are often occluded by desquamated necrotic cells and/or granular casts. Granular casts also occur commonly in distal tubules and collecting ducts. Multifocally, epithelial regeneration, in which tubules are lined by flattened to low cuboidal epithelium with basophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, is present. Other changes include mild interstitial edema, occasional small collections of lymphocytes in the cortical interstitium, and scattered mineralized tubules.

The clinical course and renal lesions are similar to those reported in cats ingesting Easter lily (Lilium longiflorum). Ingestion of blooms or leaves of Lilium sp. (Easter lily, tiger lily, Asiatic hybrids) and Hemerocallis (daylily) can produce nephrotoxic tubular necrosis (nephrosis) in cats. The toxic principle is unknown. Treatment of cats within 6 hours of ingestion with an emetic, activated charcoal, saline cathartic, and/or fluid diuresis has prevented poisoning. Cats not recognized as being poisoned until 18 or more hours after ingestion have died.

AFIP Diagnosis: Kidney: Necrosis, tubular, acute, diffuse, with granular and proteinaceous casts and tubular regeneration, Siamese-cross, feline.

Conference Note: The kidney excretes wastes, maintains fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, and is a major site of hormone production (erythropoietin, vitamin D3, and renin). Toxic injury to the kidney can affect any one or all of these functions. The kidney is extremely susceptible to toxic insult because of its specialized blood-flow and ability to concentrate solutes. Renal toxins are concentrated in tubules when water and electrolytes are reabsorbed, exposing tubular epithelial cells to increased amounts of the toxin. Some nephrotoxins are reabsorbed or secreted by the tubular epithelial cells (ie. gentamicin) and accumulate in high concentrations within these cells. Additionally, the countercurrent mechanism can greatly concentrate toxins within the medulla.

The specialized renal blood-flow, necessary for maintenance of the countercurrent mechanism, makes the medulla and medullary ray extremely susceptible to hypoxia and contributes to toxic injury. The kidney receives approximately 25% of the cardiac output; however, only a tenth of this blood reaches the medulla via the vasa recta. Additionally, nephrotoxic injury to tubular epithelial cells causes the release of thromboxane and endothelin, both of which are potent vasoconstricters. These cellular products further reduce renal blood-flow and oxygen tension.

The combination of hypoxia and toxic influences on the tubular epithelial cells results in impaired energy production and cellular respiration, damage to cell membranes, and interruption of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. These changes cause acute tubular necrosis, and if the damage is extensive, acute renal failure and death.

Contributor: G. D. Searle, 4901 Searle Parkway, Skokie, IL 60077.

References:

1. Carson T.L., Sanderson T.P., Halbur P.G.: Acute nephrotoxicosis

in cats following ingestion of Lily (Lilium sp.) In: Proceedings

37th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Veterinary

Laboratory Diagnosticians, Grand Rapids, MI, 1994.

2. Mullaney T.P., Slanker M.R., Poppenga R.H.: Easter lily associated nephrotoxicity in cats. In: Proceedings of 35th Annual Meeting of North Central Conference of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Madison, WI, 1993.

3. Epstein FH: Hypoxia of the renal medulla-Its implications for disease. New Eng Jour Med, 332(10):647, 1995.

Signalment: Adult Hereford bull.

History: Slaughter animal, normal antemortem.

Gross Pathology: 2 cm sized mass in heart (green and fibrotic) and greenish discoloration in lungs.

Laboratory Results: None submitted.

Contributor's Diagnosis and Comments: Morphologic diagnosis: Mast cell tumor, heart and lungs.

The myocardium is infiltrated and replaced by loose sheets and cords of mast cells, fibrosis, and extravasated erythrocytes. The mast cells have round to oval to reniform nuclei with prominent, often central, nucleoli and abundant greyish-brown granular cytoplasm. Mitotic figures are not evident but occasional cells are binucleated. These cells extend into the epicardium and epicardial fat. The epicardial surface of the heart is covered by papillary projections of hypertrophied mesothelial cells. Pale yellow hyaline material is scattered between these cuboidal to polyhedral cells. Areas of necrosis and mineralization are characterized by foci of amorphous basophilic granular material.

Alveolar and lobular septa of the lungs are thickened by a similar infiltration of mast cells, eosinophils, proteinaceous fluid and fibrin. Fibrin thrombi fill septal lymphatic vessels. Alveolar spaces are filled with proteinaceous edema fluid and red blood cells.

AFIP Diagnosis: Heart: Mast cell tumor, Hereford, bovine.

Conference Note: Mast cell tumors can be found in any domestic species. They must be differentiated from nodular accumulations of mast cells that may occur in parasitic, mycotic, allergic, or idiopathic diseases. Mast cell tumors are composed of sheets of round cells that are often admixed with eosinophils and abundant collagen fibers. Degeneration of the collagen is common. Neoplastic mast cells usually have moderate amounts of amphophilic granular cytoplasm. The nuclei are often centrally located and round.

In cattle, mast cell tumors have been reported in the skin, with and without metastases, and in various tissues including the heart, lung, spleen, mediastinum, peritoneum, and tongue. Cattle of all ages, including calves, are affected.

Mast cell tumors account for approximately 20% of all canine skin tumors. In dogs, mast cell tumors are often graded based upon the degree of cellular atypia and infiltration. High grade tumors are more likely to metastasize, most commonly to the regional lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Post-surgical recurrence of cutaneous mast cell tumors is common because they are poorly delineated and tend to infiltrate widely.

Cats develop cutaneous and visceral mast cell tumors. These tumors appear to be separate diseases and not metastatic extensions of one or the other. Feline cutaneous mast cell tumors are less infiltrative than those in dogs and do not metastasize as frequently. Siamese cats are predisposed to a second histologic type of mast cell tumor that occurs in the cat. These tumors tend to be multiple, and the neoplastic mast cells resemble histiocytic cells and often do not display metachromatic granules when stained with Giemsa, toluidine blue, or Luna mast cell stains.

Equine mast cell tumors are benign and frequently have more extensive mineralization, collagen degeneration, and vascular necrosis than those in other animals.

Contributor: USDA, FSIS, Eastern Laboratory, P.O. Box 6085, Athens, GA 30604.

References:

1. J.E. Hill, K.A. Langheinrich, L.C. Kelley: Prevalence and Location

of Mast Cell Tumors in Slaughter Cattle. Vet Pathol 28:449-450,

1991.

2.Yager JA, and Scott DW: The skin and appendages in of Domestic Animals, Jubb KVF; Kennedy PC; and Palmer N eds, Academic press, vol 1 pp. 727-29, 1993.

International Veterinary Pathology Slide Bank:

Laser disc frame #1919, 2827, 2829, 3264, 3912-15, 4004-5, 4465-69,

4779-80, 5942, 5950-1, 6869-71, 7889, 9090, 9451, 9665-61, 9728,

9733, 9962, 9972, 10112, 10720-24, 10792-3, 11004, 11023-6, 11542-4,

11597, 12963, 13407, 13448, 14798, 14863-5, 14891-6, 19148, 19876-8,

21553, 22168, and 22773-6.

* The American Veterinary Medical Association and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists are co-sponsors of the Registry of Veterinary Pathology. The C.L. Davis Foundation also provides substantial support for the Registry.